Chinatown, Deadwood, South Dakota

Chinatown was a historic ethnic enclave in Deadwood, located in Lawrence County in the U.S. state of South Dakota. It became the largest Chinatown of any city east of San Francisco at the time.[1] Notable figures of Deadwood's Chinatown include Fee Lee Wong, who made his way to the Black Hills during the 1870s for the Gold Rush.[2] There are many cultural and economic differences that made the Chinese community distinct such as success with laundry establishments and the structure of Chinese families.[3] The Chinese community is no longer there like it was at the end of the 19th century.[4] Archeological excavations have tried to document and identify Deadwood's Chinatown artifacts and structures, in order to gain a better idea of what that occurred in these areas. These efforts will help better understand what the lives of Chinese members in South Dakota was like.[5]

Background

Location

Deadwood is located at 44°22′36″N 103°43′45″W. [6] The city was named after dead trees that were present in the gulch that it is located in. Deadwood is located in a mountain range called the Black Hills, which are named because of how dark they look from a distance, as they are heavily covered in evergreen trees.[7] The Lakota name for the hills is "Pahá Sápa" which means "hills that are black."[7] The mountains within the Black Hills are made of shale, sandstone, limestone, and granite.

History of Deadwood, South Dakota

Deadwood (Lakota: Owáyasuta; "To approve or confirm things")[8] is a city in Lawrence County, South Dakota of the United States. The city of Deadwood is located within the Black Hills, an isolated mountain range that extends from western South Dakota into Wyoming. After arriving in the Hills during the 18th century, the Lakota Sioux claimed the land and it became central to their culture. In the year 1868, the United States government signed the Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868), which promised that the Black Hills would remain free from white settlement forever. However, beginning in the 1870s, white squatters arrived and began illegal settlement on the Lakota's land.

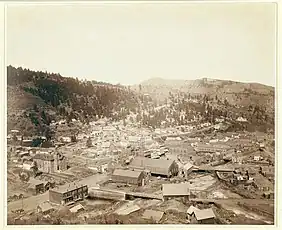

In 1874, General Armstrong Custer led an expedition into the Black Hills where he announced there was indeed gold present on the land. As a result, prospectors began arriving in large quantities in search of the economic prospects that this discovery promised. This gold rush along the Whitewood Creek made Deadwood City a thriving community within the Black Hills. Previous to the rush, Deadwood had been a small mining camp, but with masses arriving, Deadwood was transformed into an integral part of frontier society. By 1877, around 12,000 people had officially settled in Deadwood with estimates of the population reaching 25,000 in 1876.[9] Deadwood obtained a reputation for "lawlessness" as it became known for prostitution, gambling, and violence among its residents.[10] Notable "outlaws" and gunmen such as Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane are buried within the city's cemetery on Mount Moriah.[11]

Establishment of the Chinatown

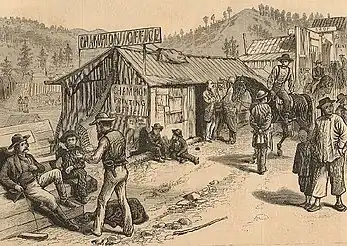

In addition to Deadwood's frontier culture, it was also home to the largest Chinatown of any city east of San Francisco.[1] Although Chinese immigrants also resided multiple areas of the West, many moved to Deadwood following the Gold Rush of this time. As early as 1875, the Black Hills Daily Times began to report that "rice and the 'other necessities of life' " were being transported by train for the "so-called 'Celestial chuckleheads from the Flowery Kingdom.' " [1] The same paper also reported Chinese immigrants who were moving towards Deadwood from Denver, Colorado.[12] The U.S. Census of 1880 lists 116 individuals,[13] but local historians suggest that as many as 400 Chinese individuals, including 14 women, resided in this Chinatown.[4] These individuals established themselves in a quarter of land between Deadwood and Elizabethtown and created what would become "a cultural, social, and economic nucleus for many Chinese living and working in the surrounding smaller mining camps and towns."[14]

Economy

Prospecting

The majority of Chinese immigrants came to the Hills to participate in other business ventures, but a few became involved in the Gold Rush. Historical estimates have suggested that white prospectors only extracted about 65% of the available gold within a specific area before moving on to another claim.[1] Chinese immigrants were known for their resilient approaches within these industries and would rework old claims after white settlers had moved through.[15] Their ability to make a profit was often criticized by white miners who claimed: "the Chinese were increasing their income by claim and sluice box thievery."[16][1] Some miners and Deadwood citizens, in contrast, praised the

Chinese and exhorted white miners to learn from them in order to become more successful.[17]

Laundry establishments

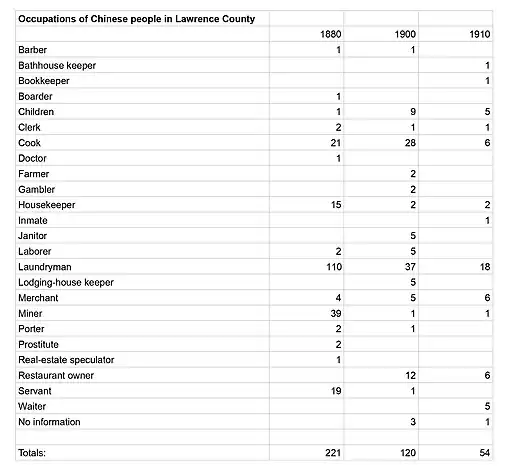

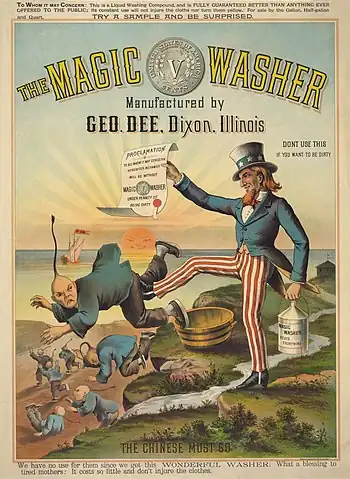

While some had arrived in the Dakota territory for prospects of Gold, others had arrived with the intention of beginning other establishments. A major economic force within the historic Chinatown was the laundry or "washee houses."[18][19] Descriptions of the Chinatown often refer to the numerous laundry establishments that lined the main square.[20] The demand for washing houses was high due to the large amounts of mining that took place in the area. Miners from both Chinatown and Deadwood used these laundry houses to have their garments cleaned.[21] In the year 1880, the occupation of laundryman was the highest listed job of the entire county at 110 individuals, the second highest being mining at 39.[22] The attraction of self-employment, consistency of clientele, and profit all lead the majority of Chinese immigrants within the county to pursue this career.[23] Most Chinese establishments charged 25 cents for a shirt and profits could sometimes come out to as much as 10 dollars daily.[23]

White members of Deadwood expressed feeling discontent with the Chinese dominance of this industry and advised women to try opening their own laundries to break the monopoly. In 1880, two white women opened the Minneapolis Laundry. They were quickly outsold as all of the Chinese laundries simultaneously lowered prices, placing them out of business, only to raise prices again once they were closed.[24][23] In response to Chinese success, a territorial law was passed in 1887 to try and limit the ownership of laundries to "American Citizens or those intent on becoming one."[25] In response, many Chinese announced their intention to become citizens and stopped paying licensing fees in protest of the discrimination.[23] These legislative acts did little to curb Chinese dominance within the industry and in 1892, 8 out of 9 of listed laundry outlets were still owned by Chinese individuals.[26]

Additional business ventures

In addition to these two dominant occupations, Chinese immigrants engaged in other capital ventures. Business owners like Wong Fee Lee, who owned the Wing Tsue Emporium, as well as Hi Kee, who owned the Hi Kee Company, provided articles in order to continue maintaining traditional ways of Chinese life, customs, and ceremonies while in the United States.[1] Some goods included imported silk, tea-making supplies, sandals, and egg-shell chings.[27] A large number of Chinese individuals operated restaurants that aimed to cater to the miners' appetites. Bang Wong, or Benny, owned and operated the OK Cafe, while another cafe called the Philadelphia Cafe was incredibly popular.[1] For dessert, Benny was known to often serve apple pie and other classical American dishes. These diners also offered more traditional Chinese dishes, such as chicken rice soup and home-brewed rice whisky.[27] In 1898, two Chinese men opened a hotel called the "Dublin Hotel." They were evaluated in the Black Hills Daily Times, which said they were "a first-class hotel in every respect."[28] The hotel charged twenty-five dollars a month, which included room and board.[23] These numerous individuals and industries participated and contributed extensively to the Chinatown and Deadwood communities.

Notable figures

Fee Lee Wong (Wing Tsue)

Fee Lee Wong, also known as Wing Tsue, made his way to the Black Hills during the 1870s for the Gold Rush. He had a shop in the Chinatown located at 566 Main Street.[2] His business was called Wing Tsue Emporium.[29] His products included silk, porcelain, herbs, tea, etc. A census taken in 1880 listed 212 Chinese individuals, including Wong. Tsue stayed in the area and became a notable businessman for over four decades. His children attended public schools and Sunday schools in Deadwood. Eventually, Tsue returned to China in 1902 and had trouble coming back to Deadwood as a result of immigration restrictions of the time.[2] A U.S. government official arranged for him to return to Deadwood. His building loan defaulted in 1915 and was bought by the bank in Deadwood. In 1919, his family returned to China again following a stroke Tsue had. He eventually died in China in 1921.[2]

Culture

Segregation

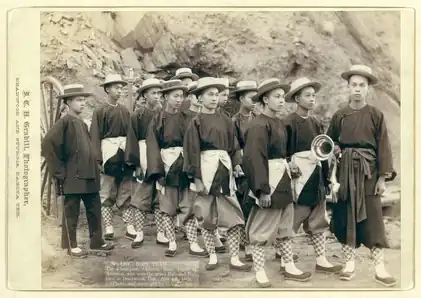

The Chinatown was developed in Deadwood in 1877.[30] Collective living was practiced among the Chinese community and helped to unify the entire Deadwood community. Culture and customs were important for Chinese individuals to confront an unfamiliar environment in a different, foreign country. De facto segregation occurred in these areas as a mechanism to deal with this unfamiliar environment.[5] Despite this De facto segregation, Chinese individuals still participated within the larger Deadwood community economically and culturally.[23] They organized fire fighting "Hose Teams" and participated in races and rallies during July 4 festivities in order to show which Chinese team was better.[31] These interactions helped overcome aspects of separation that may have been present.[31]

Family units and cultural practices

There was a lack of central family units for many Chinese individuals since immigrants were mostly male. The mentality was to further individual economic growth, which was driven by the Gold Rush taking place in the Black Hills.[5] Traditional foods were imported from China and were used habitually.[5] Clothing materials were an assortment of traditional cultural clothing and American clothing. The practice of binding feet occurred among the Chinese community at the end of the 19th century. Also, tobacco and opium were another key social practice within not only the Chinese community but the Deadwood community as a whole. The Chinese community in Deadwood maintained traditional mortuary practices for individuals who died, including parades and placing offerings with the body.[14]

Archeological excavations

Cultural artifacts and structures have not been documented well. Recently burned structural remnants showcased an indoor area where gaming activities occurred.[5] Gambling was a common pastime and showcased interactions between the Chinese culture and other cultures in the Deadwood area.[14] The process of archaeological excavation of Chinese artifacts in the area is still undergoing to further knowledge of Chinese culture in Deadwood, South Dakota during the 19th and 20th centuries. These artifacts are examined for two goals. To document and inventory Deadwood Chinatown artifacts and to gain an idea of cultural activities that occurred in these areas. These artifacts help better understand what the lives of Deadwood residents, including the Chinese, were like.[5]

Anti-Chinese discrimination

Labor participation

Despite intense oppression at the time, Chinese immigrants in Deadwood experienced less discrimination than in other parts of the United States.[14] However, some groups still expressed negative feelings towards the group of immigrants. Towards the later half of 1877, changes in the mining labor industry were taking place. Rather than working independently, corporate-owned mines were contracting labor. The Black Hills Times reported that "500 Chinese are expected to start arriving daily."[32] Reports like these evoked racist reactions from the mining community, who saw the Chinese as a direct threat to their financial stability. It was a common perception that these immigrants were willing to work for fewer wages than the typical mining salary of $4 to $7 of that day.[33] This tension led to the first organizational resistance in March 1878. J.O. Reed held a large gathering and created the first Caucasian League in the Black Hills, intent on protecting "white interests."[1][34] The League was supported by the Miners Union and they repeatedly gave speeches expressing their disinterest with the continued immigration of the Chinese to the Black Hills.[1] On one occasion, they stated during a speech that "bills have been presented in Congress to regulate the immigration of Chinese to this country, and for the benefit of our working classes, we hope they will pass."[35] Additionally, woodworking industry members voiced complaints about the Chinese workers who were participating in their industries.[36] Each group protested the Chinese immigrants through speeches, public displays of protest, and creating committees that would try to provide ultimatums to Chinese workers and their employers.[1]

In response to these organizations, the Chinese chose to respond through a written appeal. Kuong Wing, a member of the Chinatown community, attempted to reassure miners by stating: "I have undertaken to stop such influx of my people as shall tend to interfere with the labor of white men in the mines of this country, and engage that no immigration of my people shall visit the Hills, except to engage in the lighter occupations of washing, cooking and house servants. I am authorized to make the above statement public by all the Chinese inhabitants of this city who will co-operate with me in this matter."[37] An additional promise was made later to woodworking industry members that the Chinese would continue to only engage in "the lighter occupations."[38] Although some immigrants did continue working in mining and "lighter occupations," the large, numbered migration that had been predicted never materialized, and these economic worries because less prominent.[1] After this response from Chinese community members, the Black Hills did not see another collective anti-Chinese campaign or organized violent incidents again.[1]

Chinese Exclusion Acts

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a federal law of the United States signed on May 6, 1882, that prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers. Before its passage into federal law, the act was preceded by Anti-Chinese and Xenophobic driven rhetoric and violence.[39] Similar to the arguments that many in Deadwood were expressing, Chinese immigrants provided cheap labor for large industries within the United States. This was often seen as a direct threat to the economic opportunities of Native US citizens.[40] The passage of the Act made the future possibility of immigration nonexistent for Chinese laborers and it impacted immigrants already within the United States.[41]

Over 100,000 Chinese individuals immigrated to the United States in the 30 years preceding the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act. The anti-Chinese movement, especially in California, culminated in the passing of laws against the Chinese community.[42] It was not until the 1870s that the "closing of America’s gates" phrase was used by California officials.[3] Despite earlier treaties made between the Chinese and U.S. government, the Burlingame Treaty changed the original treaty and allowed more regulatory laws to be passed by the U.S. government. The Page Law barred Asian individuals connected or suspected of prostitution and Asian individuals who held contracts of labor a few years before the Chinese Exclusion Act.[3] The Chinese Exclusion Act was passed and was written originally to last for ten years. It would eventually get extended at the ten-year mark and would continue to be in United States law for over half a century.[42] Its significance in relation to the anti-Chinese movement greatly influenced the nation's immigration policy well into the next century. The exclusionary acts did not apply to specified exceptions of individuals who were considered of a higher socioeconomic status. The fluidity of individuals who performed jobs under multiple statuses were vulnerable and often classified under laborer.[42] One of the biggest consequences of these acts was the lasting racialization and racism that would affect the Chinese community and other immigrant groups from Asia such as Japanese, Indian, Korean, etc.[3] The implications of these actions are seen within the population of the Chinatown as there was only a listed 73 Chinese individuals in 1900, with the population continually declining after that.[43]

Decline

The Panic of 1893 was the result of the collapse of the silver mining industry and it touched off an economic depression that lasted for 3 years.[44] When this industry dropped, mines and the businesses that surrounded them closed. Majority of the Chinatown's population were young single male laborers who had come to participate in the mining industry. As a result, most of the Chinese immigrants in Deadwood left following this collapse, while others left later into the early 20th century.[14] Many members of the Chinatown, such as Wing Tsue and Ban Wong who were notable businessmen, returned to China.[1] Death, the Chinese Exclusion Act, fewer economic opportunities, and a desire to return to their homeland all affected the declining population of the Chinatown in Deadwood.[5] Ching Ong is said to have been "the last Chinese individual to have left the town in 1931 after having lived there for over 45 years."[4]

Legacy

Deadwood, South Dakota has survived despite economic difficulties and three large fires that threatened to plunge the town out of existence.[45] Although the Chinatown no longer exists, its memory lives on through the continuation of Deadwood as a popular tourist attraction. While the town now is considered a national historic landmark,[29] Deadwood is different from what it was at the end of the 19th century. Once gambling was made legal again, Deadwood began to boom at the end of the 20th century.[45] Now there are hotels, casinos, spas, and all kinds of amenities/services that make Deadwood into an established tourist town.[45] Archeological work is taking place to better understand Deadwood's historic Chinatown and to uncover more about the society that it resided in.[5] As further research is conducted, more can be understood about this city and the legacy it has left within the Black Hills.

References

- Anderson, Grant K. (1975). "Deadwood's Chinatown" (PDF). South Dakota State Historical Society. 5 (3).

- "Encyclopedia of the Great Plains | WONG, FEE LEE (WING TSUE) (ca. 1846-1921)". plainshumanities.unl.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- Lee, Erika (2002). "The Chinese Exclusion Example: Race, Immigration, and American Gatekeeping, 1882-1924". Journal of American Ethnic History. 21 (3): 36–62. doi:10.2307/27502847. ISSN 0278-5927. JSTOR 27502847. S2CID 157999472.

- David A. Walker, Deadwood: The Golden Years. By Watson Parker. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1981. xiv + 302 pp. Maps, illustrations, notes, selected bibliography, and index.), Journal of American History, Volume 69, Issue 2, September 1982, Pages 468–469, doi:10.2307/1893880

- Fosha, Rose Estep (2003). "The Archaeology of Deadwood's Chinatown: A Prologue" (PDF). South Dakota Historical Society. 33 (4) – via JSTOR.

- "Gazetteer Files". 2021-02-24. Archived from the original on 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- Black Hills National Forest - About the Forest. www.fs.usda.gov/main/blackhills/about-forest#:~:text=The%20name%20 %22Black%20Hills%22%20comes,the% 20surrounding%20prairie%2C%20appear%20black.

- "NLD Online v.3.0". 2016-10-18. Archived from the original on 2016-10-18. Retrieved 2023-04-04.

- Deadshot in Deadwood: Pettigrew Visits the Black Hills. Reprint of: The Sunshine State Magazine. Sioux Falls, SD: Siouxland Heritage Museums. 2002 [March, 1926]. p. 7.

- Berrettini, Mark L. (2007). "No Law: "Deadwood" And The State". Great Plains Quarterly. 27 (4): 253–265. ISSN 0275-7664.

- Bidwell, Laural A. (10 December 2013). Moon Mount Rushmore & the Black Hills: Including the Badlands. Avalon Travel Publishing. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1-61238-081-0

- 8. Black Hills Daily Times, 14 Apr. 1877. The article further stated that "they are coming fully equipped for the mining business."

- U.S. Bureau of the Census 1880 Census of Population and Housing: 1880 Census. Washington D.C.

- Fosha, Rose Estep; Leatherman, Christopher (2008). "The Chinese Experience in Deadwood, South Dakota" (PDF). The Archaeology of Chinese Immigrant and Chinese American Communities. 42 (3): 97–110. JSTOR 25617514 – via JSTOR.

- Harold E. Briggs, Frontiers of the Northwest: A History of the Upper Missouri Valley (New York: D. Appleton Century Co., 1940), p. 73

- Parker, Gold in the Black Hills; Charles H. Shinn, Mining Camps: A Study in American Frontier Government (New York: Harper & Row, 1965).

- Black Hills Daily Times; 24 August 2. Deadwood, Dakota Territory.

- Agnes W. Spring, The Cheyenne and Black Hills Stage and Express Routes (Qendale, California: Arthur H. Garke Co., 1949), pp. 77.

- Black Hills Daily Times; August 1st, 1878.

- Bennett, Old Deadwood Days, p. 30 who references: Black Hills Daily Times, 1 April 1878.

- Suey, Mountain of Gold. p. 190; and Black Hills Daily Pioneer: February 18, 1888.

- U.S., Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Census of Population, 1880.

- Zhu, Liping (2003). "Ethnic Oasis: Chinese Immigrants in the Frontier Black Hills" (PDF). South Dakota Historical Society. 33 (4).

- Black Hills Daily Times: 14 July 1877; 21 Sept. 1878; 23 July 1888.

- Black Hills Daily Times; 26 March 1881.

- Lawrence County Census; roll 113, sheets 247.

- Bennett, Estelline. Old Deadwood Days, p. 28. 1982.

- Deadwood Daily Pioneer Times; as mentioned on July 3, 1898.

- "History Timeline – Deadwood History | Black Hills, South Dakota". Deadwood. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- "Deadwood History – Wild West | Black Hills, South Dakota". Deadwood. Retrieved 2023-04-06.

- Markley, Bill. "Deadwood's Lost Chinatown". True West Magazine. Retrieved 2023-04-09.

- Black Hills Daily Times. Ibid: 18 February 1878.

- Black Hills Daily Times, 30 Jan. 1878, 25 Apr. 1878. Cited: "It's a Fact." The following appeared, "that the almond-eyed celestials, on the principle of cheap labor and over production, have a corner on the market" (Black Hills Weekly Times. 2 Aug. 1879).

- Black Hills Daily Times. 26 Feb. 1878; 3 March 1878; 7 March 1878

- Black Hills Weekly Times. 1 Feb. 1878; 5 March 1878.

- Black Hills Daily Pioneer. 19 February 1888.

- "Chinese Not to Engage in Mining." Black Hills Weekly Times, 3 March 1878.

- Black Hills Daily Pioneer, 19 February 1888.

- Lew-Williams, Beth (2018). The Chinese Must Go: Violence, Exclusion, and the Making of the Alien in America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-97601-6.

- Kanazawa, Mark (2005-08-26). "Immigration, Exclusion, and Taxation: Anti-Chinese Legislation in Gold Rush California". The Journal of Economic History. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 65 (3). doi:10.1017/s0022050705000288. ISSN 0022-0507. S2CID 154316126.

- "The People's Vote: Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on 28 March 2007.

- Calavita, Kitty (2000). "The Paradoxes of Race, Class, Identity, and "Passing": Enforcing the Chinese Exclusion Acts, 1882-1910". Law & Social Inquiry. 25 (1): 1–40. doi:10.1111/j.1747-4469.2000.tb00149.x. ISSN 0897-6546. JSTOR 829016. S2CID 145532080.

- 1900 Census of Population and Housing: 1900 Census. Washington D.C.

- Encyclopedia, Colorado (2021-02-16). "Panic of 1893". coloradoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved 2023-04-05.

- "Deadwood History – Wild West | Black Hills, South Dakota". Deadwood. Retrieved 2023-04-05.