Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage

Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage,[1] compiled by the linguist and author Lin Yutang, contains over 8,100 character head entries and 110,000 words and phrases, including many neologisms. Lin's dictionary made two lexicographical innovations, neither of which became widely used. Collation is based on his graphical "Instant Index System" that assigns numbers to Chinese characters based on 33 basic calligraphic stroke patterns. Romanization of Chinese is by Lin's "Simplified National Romanization System", which he developed as a prototype for the Gwoyeu Romatzyh or "National Romanization" system adopted by the Chinese government in 1928. Lin's bilingual dictionary continues to be used in the present day, particularly the free online version that the Chinese University of Hong Kong established in 1999.

Front cover of Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage | |

| Author | Lin Yutang |

|---|---|

| Country | Hong Kong |

| Language | Chinese, English |

| Publisher | Chinese University of Hong Kong |

Publication date | 1972 |

| Media type | print, online |

| Pages | lxvi, 1720 |

| ISBN | 0070996954 |

| OCLC | 700119200 |

| Website | http://humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/Lexis/Lindict/ |

History

Lin Yutang (1895-1976) was an influential Chinese scholar, linguist, educator, inventor, translator, and author of works in Chinese and English.

Lin's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage was his second lexicographical effort. From 1932 to 1937, he compiled a 65-volume monolingual Chinese dictionary that was destroyed by Japanese troops during the Battle of Shanghai in 1937, except for 13 volumes that he had shipped earlier to New York.[3]

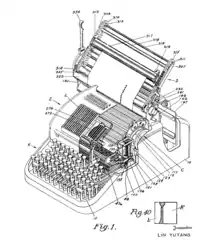

Lin Yutang's "Instant Index System" for characters inspired his invention of the Ming Kwai Chinese typewriter in 1946. Users would input a character by pressing two keys based upon the 33 basic stroke formations, which Lin called "letters of the Chinese Alphabet".[4]

Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage was the first major Chinese‐English dictionary to be produced by a fully bilingual Chinese instead of by Western missionaries.[3] In the history of Chinese lexicography, missionaries dominated the first century of Chinese‐English dictionaries, from Morrison's A Dictionary of the Chinese Language (1815-1823) to Mathews' Chinese-English Dictionary (1931, 1943).[3]

In the period between Mathews' and Lin's dictionaries, both the Chinese and English vocabularies underwent radical changes in terminology for fields such as popular culture, economics, politics, science, and technology. Lin's dictionary included many neologisms and loanwords not found in Mathews', for example (in pinyin), yuánzǐdàn 原子彈 " atomic bomb", hépíng gòngchǔ 和平共處 "peaceful coexistence", xị̌nǎo 洗腦 "brainwash", tàikōngrén 太空人 "astronaut", yáogǔn 搖滾 "rock 'n' roll", and xīpí 嬉皮 "hippie".

The history of Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage began in late 1965, when Lin and Li Choh-ming, the founding Vice-Chancellor of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, made plans for compiling a new Chinese-English dictionary as a "lasting contribution to knowledge".[5] When the dictionary was published, Lin acknowledged that Li's "vision and enthusiastic support" made the compilation project possible. Lin started working on the dictionary in Taipei, and in the spring of 1967, he accepted the position of Research Professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.[6] After completing the manuscript in the spring of 1971, Lin moved to Hong Kong, where his former student Francis Pan and a team of young Chinese University graduates assisted him with copyediting, research, and final preparations.[3]

Li Choh-ming also contributed the dictionary's foreword (in Chinese and English) and title Chinese calligraphy seen on the cover. Li says that a good Chinese-English dictionary should provide an "idiomatic equivalence" of terms in the two languages, and derides previous dictionaries for rendering fèitiě 廢鐵 as "old iron" when it should "obviously" be "scrap iron".[5] However, old iron is perfectly good British English usage.[7]

This first edition was bilingually titled Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage or Dāngdài Hàn-Yīng cídiǎn (當代漢英詞典). Sponsored by the Chinese University of Hong Kong, this book was printed in Japan by Kenkyūsha, which is known for publishing high-quality dictionaries, and was distributed by McGraw-Hill in the United States. The original edition included three indexes: Lin's idiosyncratic "instant" index for looking up traditional Chinese characters, an alphabetical English index, and an index of about 2,000 simplified Chinese characters. However, many users unfamiliar with Lin's character indexing system found the dictionary difficult to use, which led to the following supplement.

In 1978, The Chinese University Press published the Supplementary index to Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage or Lín Yǔtáng dāngdài Hàn-Yīng cídiǎn zēng biān suǒyǐn (林語堂當代漢英詞典增編索引), which indexed by Wade-Giles romanization and by the 214 Kangxi radicals.[8]

The 1987 revised edition The New Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary or Zuìxīn Lín Yǔtáng dāngdài Hàn-Yīng cídiǎn (最新林語堂當代漢英詞典), which was edited by Lai Ming (黎明) and Lin Tai-yi, Lin Yutang's son-in-law and daughter, has about 6,300 character head entries and 60,000 compounds or phrases, said to be "what general readers are likely to encounter or likely to use in their daily lives and studies".[9] Compared with the 1720-page original edition, the 1077-page new edition has approximately 1,700 fewer head entries and 40,000 more phrases. The revised edition has five indexes: numerical Instant Index System, simplified "Guoryuu Romatzyh", Wade-Giles, Mandarin Phonetic Symbols, and 214 radicals.

A team of scholars at the Chinese University of Hong Kong Research Centre for Humanities Computing developed a free web edition of Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage and published it online in 1999. The web edition comprises a total of 8,169 head characters, 40,379 entries of Chinese words or phrases, and 44,407 explanatory entries of grammatical usage. Chinese character encoding is in the Big5 system (which includes 13,053 traditional Chinese characters), which does not encode simplified Chinese characters or uncommon characters (represented as "□" in the dictionary) included in Unicode's 80,388 CJK Unified Ideographs. The web edition dictionary replaces Lin Yutang's obsolete Gwoyeu Romatzyh system with modern standard pinyin romanization, which users can hear pronounced through speech synthesis. It also abandons Lin's obsolete Instant Index System, which "has not been widely used since its inception", and provides three machine-generated indexes by radical, pinyin, and English.

Content

Lin's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage comprises approximately 8,100 character head entries and 110,000 word and phrase entries.[10] It includes both modern Chinese neologisms such as xǐnǎo 洗腦 "brainwash" and many Chinese loanwords from English such as yáogǔn 搖滾 "rock 'n' roll" and xīpí 嬉皮 "hippie". The lexicographical scope "includes all words and phrases that a modern reader is likely to encounter with(sic) in reading modern newspapers, magazines and books".[11] The dictionary contains an English index of over 60,000 words, which effectively serves as an English-Chinese dictionary. It also includes a table with 2,000 simplified Chinese characters that had come into common use in the People’s Republic of China during the 1950s and 1960s.

Lin Yutang's dictionary introduced two new Chinese linguistic systems that he invented, the Instant Index System for looking up characters and Simplified Guoryuu Romatzyh for romanizing pronunciations. Lin claimed a third innovation of being the first dictionary to determine parts of speech for Chinese words, but that distinction goes to the War Department's 1945 Dictionary of Spoken Chinese.[12][10]

Collation in Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage is by means of Lin's numerical Instant Index System for characters, which he describes as "the culmination of five decades of research". Lin previously developed this system for selecting characters with his 1946 Ming Kwai Chinese typewriter (above). The system's Chinese name shàngxiàxíng jiǎnzìfǎ 上下形檢字法 meaning "character lookup method by upper and lower shape" describes how each character is assigned a four-digit (or optional five-digit) code number according to the stroke patterns in their top left and bottom right corners. In analogy to the more popular Four-Corner Method that assigns a character a four-digit code based upon graphic strokes in the four corners, plus an optional fifth digit, Lin's simpler Instant Index System is sometimes called the "Two-Corner Method".[13]

First, Lin breaks down all Chinese characters into 33 basic stroke formations, called the "letters of the Chinese Alphabet", arranged into ten groups suggested by the characters for numerals. For instance, the character for liu 六 "6" is the mnemonic basic for "letters" 亠 (60), 广 (61), 宀 (62), and 丶 (63). Second, Lin lists the "fifty radicals" (common among the traditional 214 Kangxi radicals) designated with letters A through D, as in 氵 (63A), 礻 (63B), 衤 (63C), and 戸 (63D). Third, characters that can be divided vertically into left and right components are called "split" (S), and those characters that cannot are called "non-split" (NS), thus 羊 and 義 are (NS) while 祥 and 佯 are (S).

Lin's primary rule for the Instant Index is "Geometric Determination: The tops are defined as the geometrically highest; the bottoms are geometrically lowest. They are not the first and last strokes in writing." For example, the four-digit lookup code for 言 is 60.40 since the highest upper left stroke is 亠 (60) and the lowest bottom right stroke is 口 (40). Lin's dictionary lists only three characters 言, 吝, and 啻 in the 60.40 group, but there is a further rule for code groups that list many, such as 81A.40 with ten characters like 鈷 (81A.40-1) and 銘 (81A.40-9), "The Fifth Digit: Top of Remainder" arranges the group's character entries in numerical accordance with the "top of remainder" (character minus "radical").

Romanization in Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage is by "Simplified Guoryuu Romatzyh" (Jiǎnhuà luómǎzì 簡化羅馬字, Jiaanhuah Rormaatzyh in Lin's system) that he developed in 1923 and 1924 as a prototype for the Gwoyeu Romatzyh (GR) "National Language Romanization" system adopted by the Chinese Government in 1928.[10] Lin also calls this system "Simplified Romatzyh" and "Basic GR".

Both systems represent the four tones of Standard Chinese with different spellings but Lin's simplified GR is more consistent than standard GR. For instance, the word Guóyǔ 國語 ("National Language; Standard Chinese; Mandarin") is romanized Gwoyeu in official GR and Guoryuu in Lin's simplified GR, which exemplifies the difference between systems. Pinyin 2nd-tone guó (國) is GR gwo and "basic" GR guor; and 3rd-tone yǔ (語) is yeu and yuu, respectively. Simplified GR consistently represents tone by the spelling of the main vowel in a syllable, with vowel unchanged for 1st-tone (guo), -r added for 2nd-tone guor (國), vowel doubled for 3rd-tone (guoo), and -h added for 4th-tone (guoh); and similarly yu, yur, yuu (語), and yuh. Standard GR uses these same four tonal spellings for many syllables (tones 1-4 are a, ar, aa, and ah), but changes them for some others, including guo, gwo (國), guoo, and guoh; and yiu, yu, yeu (語), yuh.

Lin Yutang said, "People who are new to this system will doubtless be disturbed by it at first. But they'll get used to it very quickly. I don't need to emphasize the point that the method of building the tone into the spelling of the word fits the modern world of telegraphy, the typewriter and the computer".[3]

Entries in Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage are lexicographically sophisticated and have accurate translation equivalents. The basic format for a head entry gives the character, the Instant Index System code, the pronunciation(s) in Simplified GR, the part or parts of speech, optionally other speech levels (e.g., "sl." for slang), English translation equivalents for the head character and usage examples of polysyllabic compounds, phrases, and idioms, subdivided by numbers for multiple meanings, and lastly a list of common Chinese words using the entry character, each given with characters, pronunciation, part of speech, and translation equivalents.[14] The dictionary distinguishes historical varieties: AC (Ancient Chinese), MC (Middle Chinese), LL (Literary Language), and Dial. (dialect); and levels of speech: court. (courteous), sl. (slang), satir. (satirical,) facet. (facetious), contempt. (contemptuous), abuse, derog. (derogatory), vulgar, and litr. (literary).[15]

Lin explains that the basic principle for translation equivalents is "contextual semantics, the subtle, imperceptible changes of meaning due to context".[16] In terms of the translational contrast between dynamic and formal equivalence, Lin placed emphasis on presenting the dynamic or "idiomatic equivalence" of words and phrases rather than rendering formal literal translations.[10]

The Chinese character 道 for dào "way; path; say; the Dao" or dǎo "guide; lead; instruct" (or 導) provides a good sample entry for a dictionary because it has two pronunciations and is polysemous.

- 道 80.83 dauh ㄉㄠˋ

- N. adjunct. A stripe, streak, course, issue: 一道光,氣 a streak of light, a jet of gas; 一道街,河 a street, a stream; … [3 more usage examples]

- N. ① Doctrine, body of moral teachings, truth: 孔孟之道,儒道 teachings of Confucius and Mencius; 邪道,左道 heresy; the Tao of Taoism, the Way of Nature which cannot be given a name; … [8 examples] ② Path, route: 快車道 speedway on city road; 街道 street; … [7 examples]

- V.i. ① To say: 說道 (s.o.) says, (followed by quotation); 笑道 say with a smile or laugh; … [7 examples] ② Guide (u.f. 導): 道之以德 (AC) guide them with morals.

- [Words] lists 27 alphabetically arranged entries from "道白 dauhbair, n., spoken part of dialogue in Chin. opera." to "道友 dauh-youu, n., friends of same church or belief, friends sharing same interest (oft. referred to drug addicts)."

The first "N. adjunct." and third "V.i." part-of-speech sections refer to grammatical "noun adjunct" or Chinese measure word and "intransitive verb".

Reception

Reviewers of Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage have praised some aspects like the translation equivalents and censured others like the "instant" character indexing system. On the one hand, New York Times reporter Peggy Durdin calls the dictionary a "milestone in communication between the world's two largest linguistic groups, the Chinese‐speaking and English‐speaking peoples".[3] On the other, the American sinologist and historian Nathan Sivin says, "Despite a good deal of meretricious ballyhoo when it was published, Lin's book does not contain significant lexicographic innovations."[17]

Reviews are mentioned by English sinologist and translator David E. Pollard, "Lin Yutang is his own worst enemy: one can visualize the hackles of reviewers everywhere rising both at his claims, which are mostly phony, and his denials, which are often untrue.".[7] After criticizing faults in Lin Yutang's dictionary, one reviewer gave a balanced conclusion, "the mistakes and omissions are far outweighed by his index system even with its kinks, and by his typable, indexable, computerizable romanization system, his generally excellent English translations, and his comprehensive and up-to-date entries".[14]

Lin Yutang's confusing Instant Index System has been widely criticized. Nathan Sivin surveyed users of the numerical system and found that most "consider it a nuisance to use".[18] What Lin called an "unforgettable instant index system", proved to be "an unnecessary and not easily remembered variation on the traditional four-corner arrangement".[19] Since most students of Chinese who purchase Lin's dictionary already know the conventional 214 radical-stroke and Four-Corner systems, they "may resent having to learn a new set of tricks", says Pollard, who suggests that "the process of compiling a Chinese dictionary will always bring out the mad inventor in people".[20] Ching says Lin's system is a "praiseworthy improvement" over previous Chinese-English dictionaries, but it is not as easy to use as an alphabetically arranged dictionary. Although the name Instant Index System "promises facility and speed in locating characters", it is often "difficult to locate them "instantly"," for two major reasons: the variability of Chinese characters and cases when dictionary users interpret the rule of geometric determination differently from what Lin intended. For example, according to the rule, it would be "most logical" to search for this character chin 緊 under number 30, the horizontal stroke 一 at the top left, but it is classified under number 51, the cliff radical 厂, and no cross-references are provided.[21]

Lin's "Simplified Romatzyh" system of romanization also has detractors. While one reviewer called the romanization system "revolutionary even though it has been in existence for quite some time", and agreed with Lin that "as a learning tool, the "basic" GR is better",[21] others have been less impressed. "Casual users unwilling to master the complexities of its arrangement and transcription will find it practically inaccessible".[18] The system "still remains daunting unless the reader finds compelling reasons" to use Lin's dictionary.[19]

Many reviewers have commented on the wide range of entries in Lin's dictionary, which is aimed not at students of a special field, but at "modern, educated man".[3] Lin Yutang's introduction says many dictionary entries come from Wang Yi's (1937-1945) Gwoyeu Tsyrdean 國語辭典 "Dictionary of the National Language".[22] Sivin calls Lin's dictionary "largely an English translation of the excellent" Gwoyeu Tsyrdean.[17] Pollard criticizes Lin's list of Chinese terms that had "never been carefully noted" prior to his dictionary, since all that he did was to translate the half that are "carefully noted" in the Wang's dictionary, while Mathews' Chinese-English Dictionary (1931, 1943) also includes half of the terms. "To have gutted the Gwoyeu Tsyrdean would by itself have been a worthwhile job, but he has done more, by selectively expanding and explaining and, particularly, by adding a host of new terms and expressions".[23]

Eugene Ching says that Lin Yutang's choice of modernized entries "makes his dictionary the most up-to-date available today".[21] Ching analyzed the 120 entries under chu 出 "go out; come out" in Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage with the 170 in Wang's Gwoyeu Tsyrdean and found that Lin added and eliminated certain types of lexical items. In the process of addition, Lin not only incorporated new lexical items (e.g., taanbair 坦白 "confess one's own guilt in communist meeting"), but also included new meanings for old items ("a girl secretary in office kept for her looks rather than work" for huapirng 花瓶(兒) "flower vase"). Eliminated items include: obsolete or rare terms (chudueihtzy 出隊子 "a poetic pattern"), expressions whose meanings can be synthesized (chubaan faa 出版法 "publication codes"), and highly literary expressions (chu-choou-yarng-jir 出醜揚疾 "to expose the ugliness and defects"). However, this process of elimination gave rise to mistakes, such as omitting some common literary clichés (chu-erl-faan-er 出爾反爾 "outstanding") and overlooking frequently used meanings ("to complete the apprenticeship" for chu-shyw 出師 "to march army for battle").

Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage has been repeatedly criticized for not including more vocabulary developed in the PRC. Lin's dictionary "covers essential Chinese as spoken and written today outside the People's Republic and ignores terminology peculiar to mainland China".[18] Dunn estimates that only about 1% of the total number of entries are "Chinese Communist words and phrases", such as xiàfàng 下放 "send down urban cadres to work at a lower level or do manual labor in the countryside" and Dà yuè jìn 大跃进 "Great Leap Forward".[10] Although Lin's dictionary includes words from many modern sources, "What is left out, unfortunately for most potential users, is the vocabulary developed in the People's Republic".[24]

Reviewers have frequently commended Lin's dictionary for its accurate English translation equivalents of each head character and its multiple usage examples. Sivin says that "in accuracy of translation, clarity of explanation, and colloquialism of English equivalents this is greatly superior to any other dictionary in a Western European language".[18] "Lin Yutang's business is in words, and he knows how they are manipulated; he also has a very wide knowledge of things Chinese, which helps him immeasurably in his task. Of course there are instances where better English equivalents could have been found, and his scholarship is not infallible, but it probably is true, as Professor Li claims, that he is uniquely qualified, among individuals, to bridge the gap between the two languages".[24]

Several scholars have found faults with the dictionary's treatment of parts-of-speech and syntactic categories. Lin's main claim "to have solved at one stroke the problem of Chinese grammar by classifying words as nouns, verbs, adjectives, adverbs and prepositions, would need some justifying, since it is ultimately based on the premise that Chinese is the same as Latin", and a scheme that is only a "pis-aller should not be presented as a revelation".[24] Ching says the best way grammar can be taught in a dictionary is through sample phrases or sentences, but without appropriate examples, the "students depending upon this dictionary for self-study will find the grammatical labels alone not really useful".[14] Sivin describes Lin's grouping of words by English parts of speech as "linguistically retrograde and confusing, since the structure of Chinese is quite different".[17] Lin explained that, "most linguists have doubted whether Chinese has anything that could be called grammar. Well, one certainly cannot discover grammar until one recognizes and thinks in terms of whole words, which are parts of speech—nouns, verbs and so on. Then one sees that Chinese grammar exists".[3]

Lastly, Lin Yutang's dictionary has some minor mistakes.[14] One example of translation error is found under the very first entry, tsair 才; tsairmauh 才貌 "personal appearance as reflecting ability" is translationally incompatible with larng-tsair-nyuumauh 郎才女貌 "the boy has talent and the girl has looks" (under 郎) and tsair-mauh-shuang-chyuarn 才貌雙全 "to have both talent and looks" (under 全). Another example of carelessness is seen under the sequential entries shyu 戍 "Garrison; frontier guard" and shuh 戌 "No. 11 in the duodecimal cycle", where Lin warns students to distinguish the characters from each other. Yet, the chiaan 遣 entry writes the example word chiaanshuh 遣戌 "send to exile" twice as "遣戍"; an error that the revised 1987 edition corrected. Admittedly, these two ideographic characters are easily confused, xū 戌 (戊 "a weapon" and a horizontal stroke 一 signifying "to wound") "destroy; 11th" and shù 戍 (戊 "a weapon" and a dot 丶 simplified from the original 人 "person" signifying "person with a weapon") "frontier guard".[25] Eugene Ching concludes that, "Since his profound knowledge of both Chinese and English makes Lin one of the most qualified persons to work on a bilingual dictionary, it is impossible that he is ignorant of the correct translation and the correct grammar of the above examples. These mistakes can only suggest Lin's failure to proofread carefully the work of his assistants."

References

- Ching, Eugene (1975). "[A review of] Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage (by Lin Yutang)". Journal of Asian Studies. 34 (2): 521–524. doi:10.2307/2052772. JSTOR 2052772.

- Lin, Yutang (1982) [1972]. Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage 林語堂當代漢英詞典. 3rd print. Chinese University of Hong Kong (McGraw-Hill distribution).

- Pollard, David E. (1973). "[A review of] Lin Yutang's Chinese-English dictionary of modern usage". The China Quarterly. 56: 786–788. doi:10.1017/S0305741000019731.

- Sivin, Nathan (1976). "[A review of] Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage". Isis. 67 (2): 308–309. doi:10.1086/351613.

Footnotes

- Lin 1972.

- US 2613795, Yutang, Lin, "Chinese typewriter", published 1952-10-14, assigned to Mergenthaler Linotype Company

- Durdin, Peggy (1972), Finally, a Modern Chinese Dictionary, New York Times, 23 November 1972, p. 37.

- Sorrel, Charlie (2009), "How it Works: The Chinese Typewriter", Wired, 23 February 2009.

- Lin 1972, p. xvi.

- Qian Suoqiao (2011), Liberal Cosmopolitan: Lin Yutang and Middling Chinese Modernity, Brill. p. 251.

- Pollard 1973, p. 786.

- The Chinese University Press (1978), Supplementary Indexes to Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Usage, 林語堂當代漢英詞典增編索引, The Chinese University Press. 1982, 3rd print.

- Lin Tai-yi and R. Ming Lai, eds. (1987), The New Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary , 最新林語堂當代漢英詞典, Panorama Press. p. xii.

- Dunn, Robert (1977), "Lin Yutang's Chinese-English Dictionary of Modern Isage", in Chinese-English and English-Chinese Dictionaries in the Library of Congress, Library of Congress, p. 81 (81-82).

- Lin 1972, p. xix.

- Lin 1972, p. xxiii.

- Theobald, Ulrich (2000), Lin Yutang's two corners instant index system, Chinaknowledge.

- Ching 1975, p. 524.

- Lin 1972, pp. xx–xxi.

- Lin 1972, p. xxiv.

- Sivin 1976, p. 308.

- Sivin 1976, p. 309.

- Chan, Sin-wai and David E. Pollard (2001), An Encyclopaedia of Translation: Chinese-English, English-Chinese, Chinese University Press. p. 1100.

- Pollard 1973, p. 788.

- Ching 1975, p. 522.

- Wang Yi 汪怡 et al. (1937-1945), Gwoyeu Tsyrdean 國語辭典, 8 volumes, Commercial Press.

- Pollard 1973, pp. 786–7.

- Pollard 1973, p. 787.

- Bernard Karlgren, Wenlin 2016.