Chinese South Africans

Chinese South Africans (simplified Chinese: 华裔南非人; traditional Chinese: 華裔南非人) are Overseas Chinese who reside in South Africa, including those whose ancestors came to South Africa in the early 20th century until Chinese immigration was banned under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1904.[2] Chinese industrialists from the Republic of China (Taiwan) who arrived in the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s, and post-apartheid immigrants to South Africa (predominantly from mainland China) now outnumber locally-born Chinese South Africans.[3][4]

華裔南非人 华裔南非人 | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| 300,000 – 400,000[1] (2015, est.) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Durban · Johannesburg · Port Elizabeth · Cape Town | |

| Languages | |

| English · Afrikaans · Cantonese · Mandarin · Hokkien | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Overseas Chinese |

South Africa has the largest population of Chinese in Africa,[3] and most of them live in Johannesburg, an economic hub in southern Africa.

History

| South African Chinese Population, 1904–1936[5]: 177 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 1904 | 1911 | 1921 | 1936 |

| Natal Province | ||||

| Male | 161 | 161 | 75 | 46 |

| Female | 4 | 11 | 33 | 36 |

| Cape Province | ||||

| Male | 1366 | 804 | 584 | 782 |

| Female | 14 | 19 | 148 | 462 |

| Transvaal Province | ||||

| Male | 907 | 905 | 828 | 1054 |

| Female | 5 | 5 | 160 | 564 |

| Total | 2457 | 1905 | 1828 | 2944 |

First settlers

The first Chinese to settle in South Africa were prisoners, usually debtors, exiled from Batavia by the Dutch to their then newly founded colony at Cape Town in 1660. Originally the Dutch wanted to recruit Chinese settlers to settle in the colony as farmers, thereby helping establish the colony and create a tax base so the colony would be less of a drain on Dutch coffers. However the Dutch failed to find anyone in the Chinese community in Batavia who was prepared to volunteer to go to such a far off place. The first Chinese person recorded by the Dutch to arrive in the Cape was a convict by the name of Ytcho Wancho (almost certainly a Dutch version of his original Chinese name). There were also some free Chinese in the Dutch Cape Colony. They made a living through fishing and farming and traded their produce for other required goods.[6] From 1660 until the late 19th century the number of Chinese people in the Cape Colony never exceeded 100.[5]: 5–6

Chinese people began arriving in large numbers in South Africa in the 1870s[7] through to the early 20th century initially in hopes of making their fortune on the diamond and gold mines in Kimberley and the Witwatersrand respectively. Most were independent immigrants mostly coming from Guangdong Province then known as Canton. Due to anti-Chinese feeling and racial discrimination at the time they were prevented from obtaining mining contracts and so became entrepreneurs and small business owners instead.[8]

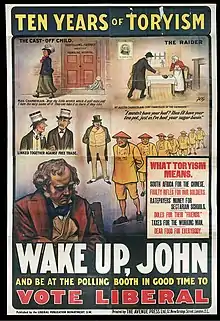

The Chinese community in South Africa grew steadily throughout the remainder of the 19th century, bolstered by new arrivals from China. The Anglo-Boer War, fought between 1898 and 1902, pushed some Chinese South Africans out of the Witwatersrand and into areas such as Port Elizabeth and East London in the Eastern Cape.[9] Areas recorded to have Chinese populations moving in to settle at the time include Pageview in Johannesburg that was declared a non-white area in the late 1800s and known as the "Malay Location"[10] Large-scale immigration into South Africa during this time was prohibited by the Transvaal Immigration Restriction Act of 1902 and the Cape Chinese Exclusion Act of 1904. A host of discriminatory laws similar to the anti-Chinese laws that sought to restrict trade, land ownership and citizenship were also enacted during this time. These laws were largely made popular by a general anti-Chinese feeling across the western world during the early 1900s and the arrival of over 60,000 indentured Chinese miners after the second Anglo-Boer War.[8]

These early immigrants arriving between the 1870s and early 1900s are the ancestors of most of South Africa's first Chinese community and number some 10,000 individuals today.[8]

Contracted gold miners (1904–1910)

There were many complicated reasons why the British chose to import Chinese labour to use on the mines. After the Anglo-Boer War, production on the gold mines of the Witwatersrand was very low due to a lack of labour. The British government was eager to get these mines back online as quickly as possible as part of their overall effort to rebuild the war-torn country.

Because of the war, unskilled African laborers had returned to rural areas and were more inclined to work on rebuilding infrastructure as mining was more dangerous. Unskilled white labour was being phased out because it was deemed too expensive. The British found recruiting and importing labour from east Asia the most expedient way to solve this problem.[5]: 104

Between 1904 and 1910, over 63,000 contracted miners were brought in to work the mines of the Witwatersrand. Most of these contractors were recruited from the Chinese provinces of Zhili, Shandong and Henan.[5]: 105 They were repatriated after 1910,[3][11] because of strong White opposition to their presence, similar to anti-Asian sentiments in the western United States, particularly California at the same time.[12] It is a myth that the contracted miners brought into South Africa at this time are the forefathers of much of South Africa's Chinese population.[5]: 103–104

Herbert Hoover, who would become the 31st U.S. president, was a director of Chinese Engineering and Mining Corporation (CEMC) when it became a supplier of coolie (Asian) labor for South African mines.[13] The first shipment of 2,000 Chinese workers arrived in Durban from Qinhuangdao in July 1904. By 1906, the total number of Chinese workers increased to 50,000, almost entirely recruited and shipped by CEMC. When the living and working conditions of the laborers became known, public opposition to the scheme grew and questions were asked in the British Parliament.[14] The scheme was abandoned in 1911.

The mass importation of Chinese labourers to work on the gold mines contributed to the fall from power of the conservative government in the United Kingdom. However, it did stimulate to the economic recovery of South Africa after the Anglo-Boer War by once again making the mines of the Witwatersrand the most productive gold mines in the world.[5]: 103

Passive resistance campaign (1906–1913)

In 1906, about 1,000 Chinese joined Indian protesters led by Mahatma Gandhi to march against laws barring Asians in the Transvaal Colony from purchasing land.[15][16] In 1907, the government of the Transvaal Colony passed the Transvaal Asiatic Registration Act that required the Indian and Chinese populations in the Transvaal to be registered and for males to be fingerprinted and carry pass books.[17] The Chinese Association made a written declaration saying that the Chinese would not register for passes and would not interact with those that did.[18] Mahatma Gandhi started a campaign of passive resistance to protest the legislation that was supported by the Indian and Chinese communities. The secretary of the Chinese Association informed Gandhi that the Chinese were prepared to be jailed alongside Indians in support of this cause.[18] On 16 August 1908, members of the movement gathered outside Hamidia Mosque where they burnt 1,200 registration certificates.[19]

Apartheid era (1948–1994)

As with other non-White South Africans, the Chinese suffered from discrimination during apartheid, and were often classified as Coloureds,[20] but sometimes as Asians, a category that was generally reserved for Indian South Africans. Today this segment of the South African Chinese population numbers some 10,000 individuals.[3]

Under the apartheid-era Population Registration Act, 1950, Chinese South Africans were deemed "Asiatic", then "Coloured", and finally:

the Chinese Group, which shall consist of persons who in fact are, or who, except in the case of persons who in fact are members of a race or class or tribe referred to in paragraph (1), (2), (3), (5) or (6) are generally accepted as members of a race or tribe whose national home is in China.[21]

Chinese South Africans, along with Black, Coloured and Indian South Africans, were forcefully removed from areas declared "Whites only" areas by the government under the Group Areas Act in 1950. Suburbs in Johannesburg with Chinese South African populations that were subject to forced removals include Sophiatown starting in 1955,[22][23] Marabastad in 1969[24][25] and the adjacent suburbs of Pageview and Vrededorp, known colloquially as 'Fietas', in 1968.[26][27] Chinese South Africans were also among those removed from the South End district of Port Elizabeth beginning in 1965.[28] These removals resulted in the formation of a Chinese township in Port Elizabeth.[29]

In 1966 the South African Institute of Race Relations described the negative effects of apartheid legislation on the Chinese community and the resulting brain drain:

No group is treated so inconsistently under South Africa's race legislation. Under the Immorality Act they are Non-White. The Group Areas Act says they are Coloured, subsection Chinese ... They are frequently mistaken for Japanese in public and have generally used White buses, hotels, cinemas and restaurants. But in Pretoria, only the consul-general's staff may use White buses .. Their future appears insecure and unstable. Because of past and present misery under South African laws, and what seems like more to come in the future, many Chinese are emigrating. Like many Coloured people who are leaving the country, they seem to favour Canada. Through humiliation and statutory discrimination South Africa is frustrating and alienating what should be a prized community.[5]: 389–390

In 1928, the liquor legislation was amended to allow Indian South Africans to purchase liquor.[30][31] Following an amendment in 1962, other non-white South Africans could purchase alcohol, but not drink in white areas.[32] In 1976, the law was amended to allow Chinese South Africans to drink alcohol in white areas.[33]

In 1984, the Tricameral Parliament was established by the government to give Coloured and Indian South Africans a limited influence on South African politics. The Tricameral Parliament was criticised by anti-apartheid groups including the United Democratic Front, who promoted a boycott of the Tricameral Parliament elections, as it still excluded Black people and had very little political power in South Africa.[34] The Chinese South African community refused to participate in this parliament.[35] Previously, the Chinese Association had expelled a member who had been appointed to the President's Council, a body established to advise on constitutional reform.[36]

Immigration from Taiwan

| Number of Chinese granted permanent residence in South Africa 1985–1995[5]: 419 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Number | |||

| 1985 | 1 | |||

| 1986 | 7 | |||

| 1987 | 133 | |||

| 1988 | 301 | |||

| 1989 | 483 | |||

| 1990 | 1422 | |||

| 1991 | 1981 | |||

| 1992 | 275 | |||

| 1993 | 1971 | |||

| 1994 | 869 | |||

| 1995 | 350 | |||

| Total | 7793 | |||

| By citizenship 1994–95[5]: 419 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizenship | 1994 | 1995 | ||

| Taiwan (ROC) | 596 | 232 | ||

| People's Republic of China | 252 | 102 | ||

| Hong Kong | 21 | 16 | ||

| Total | 869 | 350 | ||

With the establishment of ties between apartheid South Africa and Taiwan (officially the Republic of China), KMT-affiliated Taiwanese Chinese (as well as some Hong Kongers from British Hong Kong) started migrating to South Africa from the late 1970s onward. Due to apartheid South Africa's desire to attract their investment in South Africa and the many poorer Bantustans within the country, they were exempt from many apartheid laws and regulations. This created a situation where South Africans of Chinese descent continued to be classified as Coloureds or Asians, whereas the Taiwanese Chinese[37] and other East Asian expatriates (South Koreans and Japanese) were considered "honorary whites"[4] and enjoyed most of the rights accorded to White South Africans.[11]

The South African government also offered a number of economic incentives to investors from Taiwan seeking to set up factories and businesses in the country. These generous incentives ranged from "paying for relocation costs, subsidised wages for seven years, subsidised commercial rent for ten years, housing loans, cheap transport of goods to urban areas, and favourable exchange rates".[8]

In 1984, South African Chinese, now increased to about 10,000, finally obtained the same official rights as the Japanese in South Africa, that is, to be treated as whites in terms of the Group Areas Act.[33] The arrival of the Taiwanese resulted in a surge of the ethnic Chinese population of South Africa, which climbed from around 10,000 in the early 1980s to at least 20,000 in the early 1990s. Many Taiwanese were entrepreneurs who set up small companies, particularly in the textile sector, across South Africa. It is estimated that by the end of the early 1990s Taiwanese industrialists had invested $2 billion (or $2.94 billion in 2011 dollars)[38] in South Africa and employed roughly 50,000 people.[5]: 427

In the late 1990s and the first decade of the 21st century many of the Taiwanese left South Africa, in part due to official recognition of the People's Republic of China and a post-apartheid crime wave that swept the country. Numbers dropped from a high of around 30,000 Taiwanese citizens in the mid-1990s to the current population of approximately 6,000 today.[3]

Post-Apartheid

Following the end of apartheid in 1994, mainland Chinese began immigrating to South Africa in large numbers, increasing the Chinese population in South Africa to an estimated 300,000-400,000 in 2015.[1] In Johannesburg, in particular, a new Chinatown has emerged in the eastern suburbs of Cyrildene and Bruma Lake, replacing the declining one in the city centre. A Chinese housing development has also been established in the small town of Bronkhorstspruit, east of Pretoria, as well as a massive new "city" in development in Johannesburg.

In 2017 the trade union COSATU issued an apology[39] for racially charged remarks made by COSATU protesters towards a Chinese South African Johannesburg city councillor, Michael Sun.[40] In 2022 eleven people were found guilty of hate speech towards Chinese South Africans on Facebook following the airing of a Carte Blanche documentary on the inhumane treatment of donkeys slaughtered for use in traditional medicine in the People's Republic of China.[41][42]

Black Economic Empowerment ruling

Under apartheid, some Chinese South Africans were discriminated against in various forms by the apartheid government. However, they were originally excluded from benefiting under the Black Economic Empowerment (BEE) programmes of the new South African government.[20] This changed in mid-2008 when, in a case brought by the Chinese Association of South Africa, the Pretoria division of the High Court of South Africa ruled that Chinese South Africans who were South African citizens before 1994, as well as their descendants, qualify as previously disadvantaged individuals as Coloureds,[4] and therefore are eligible to benefit under BEE and other affirmative action policies and programmes. The Chinese Association of South Africa was represented by human rights lawyer George Bizos in court during the case.[43] However, Chinese South Africans who immigrated to the country after 1994 will be ineligible to benefit under the policies. In September 2015, Department of Trade and Industry deputy director general Sipho Zikode clarified who the ruling was meant to benefit. He said that not all Chinese in South Africa were eligible for BEE. He confirmed that only Chinese who were South African citizens prior to 1994, numbering "about 10,000" were eligible.[44]

Immigration of Mainland Chinese

The immigration of mainland Chinese, by far the largest group of Chinese in South Africa, can be divided into three periods. The first group arrived in the late 1980s and early 1990s along with the Taiwanese immigrants. Unlike the Taiwanese immigrants, lacking the capital to start larger firms, most established small businesses. Although becoming relatively prosperous a large number of this group left South Africa, either back to China or to more developed Western countries, around the same time and for much the same reason as the Taiwanese immigrants left. The second group, arriving mostly from Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces in the 1990s, were wealthier, better educated, and very entrepreneurial. The latest and ongoing group began arriving after 2000 and primarily made up of small traders and peasants from Fujian province.[3][45] There are also many Chinese from other regions in China. As of 2013, there were 57 different regional Chinese associations operating in the Cyrildene Chinatown.[46]

Although the Chinese South African community is a most law-abiding community that has maintained a low profile in modern South Africa, there is speculation that local criminal gangs in South Africa barter abalone illegally with Chinese nationals and triad societies in exchange for chemicals used in the production of drugs, reducing the need for the use of money and hence avoiding difficulties associated with money laundering.[47][48]

Notable Chinese South Africans

- Patrick Soon-Shiong (黃馨祥), surgeon and billionaire

- Chad Ho, six-time titleholder for the Midmar Mile

- Chris Wang (王翊儒), former member of the National Assembly, originally an MP for the ID, now a member of the ANC

- Eugenia Chang, member of the National Assembly, for the Inkatha Freedom Party

- Ina Lu (呂怡慧), Miss Chinese International 2006

- Sherry Chen (陈阡蕙), former Member of Parliament in South Africa, member of the Democratic Alliance

- Shiaan-Bin Huang (黄士豪), Member of Parliament of South Africa, member of the African National Congress

- Shannon Kook, actor

- Jennifer Su, television and radio personality

- Xiaomei Havard, member of the National Assembly, member of the African National Congress

- David Kan, businessman and founder of the electronics company Mustek.

See also

References

- Liao, Wenhui; He, Qicai (2015). "Tenth World Conference of Overseas Chinese: Annual International Symposium on Regional Academic Activities Report (translated)". The International Journal of Diasporic Chinese Studies. 7 (2): 85–89.

- Ho, Ufrieda (19 June 2008). "Chinese locals are black". Busrep.co.za. Archived from the original on 22 June 2008.

- Park, Yoon Jung (2009). Recent Chinese Migrations to South Africa - New Intersections of Race, Class and Ethnicity (PDF). ISBN 978-1-904710-81-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2010. Retrieved 20 September 2010.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Leonard, Andrew (20 June 2008). "What color are Chinese South Africans?". Salon.com. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Yap, Melanie; Leong Man, Dainne (1996). Colour, Confusion and Concessions: The History of the Chinese in South Africa. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 510. ISBN 962-209-423-6.

- Elphick, Richard; Giliomee, Hermann (1979). The Shaping of South African Society, 1652–1840. Wesleyan University Press. p. 223. ISBN 9780819562111. Retrieved 1 January 2016.

- Clayton, Jonathan (19 June 2008). "We agree that you are black South African court tells Chinese". The Times. London. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- Park, Yoon Jung (January 2012). "Living in Between: The Chinese in South Africa". Immigration Information Source. Retrieved 12 January 2012.

- Harris, Karen L. (1994). "The Chinese in South Africa: a preliminary overview to 1910". Sahistory.org.za. Archived from the original on 26 June 2008.

- Mapungubwe Institute for Strategic Reflection (2015). Nation Formation and Social Cohesion: An Enquiry into the Hopes and Aspirations of South Africans. Real African Publishers. p. 148. ISBN 9781920655747. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- "In South Africa, Chinese is the New Black". The Wall Street Journal. 19 June 2008.

- Nativism (politics)#Anti-Chinese nativism

- Walter Liggett, The Rise of Herbert Hoover (New York, 1932)

- "Mr Winston Churchill: speeches in 1906 (Hansard)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- Jain, Ankur (1 February 2014). "Why Mahatma Gandhi is becoming popular in China - BBC News". BBC News. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

Some 1,000 Chinese supporters joined Indians to take part in Gandhi's first peaceful protest in Transvaal province in 1906 to protest against a law that barred Asians from owning property and made it mandatory to carry identity cards, among other things.

- "Chinese had joined Mahatma Gandhi's South Africa struggle". The Times of India. 18 September 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- "Asiatic Law Amendment Act is passed in Transvaal parliament leading to increased Indian protest under MK Gandhi". South African History Online. 22 March 1907. Archived from the original on 23 June 2014. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- Bhattacharjea, Mira Sinha (2005). "Gandhi and the Chinese Community". In Thampi, Madhavi (ed.). India and China in the colonial world. New Delhi: Social Science Press. p. 160. ISBN 8187358203.

- "Tracing Gandhi in Joburg". joburg.org.za. 1 February 2012. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

It was outside the Hamidia Mosque on 16 August 1908 that Indians and Chinese set alight more than 1 200 registration certificates...

- "S Africa Chinese 'become black'". BBC News. 18 June 2008. Retrieved 28 April 2010.

- Perry, Alex (1 August 2008). "A Chinese Color War". Time. Johannesburg. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012.

- Ansell, Gwen (28 September 2004). Soweto Blues: Jazz, Popular Music, and Politics in South Africa. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 67. ISBN 978-0826416629. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Otzen, Ellen (11 February 2015). "The town destroyed to stop black and white people mixing". BBC News. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Accone, Darryl (2004). All under heaven : the story of a Chinese family in South Africa (2. impr. ed.). Claremont, South Africa: David Philip. p. 251. ISBN 9780864866486. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- Masilela, Johnny (1 January 2015). "The broken miracle of Marabastad". Mail and Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Mamdoo, Feizel (24 September 2015). "Fietas streets by any other name are not as sweet". Mail and Guardian. Archived from the original on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- Ho, Ufrieda (14 August 2012). "Fietas vanished like dream". IOL. The Star. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- "South End Museum, Port Elizabeth". southafrica.net. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- Saff, Grant R. (1998). Changing Cape Town : urban dynamics, policy and planning during the political transition in South Africa. Lanham, Md: University Press of America. p. 60. ISBN 978-0761811992. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- "Apartheid Legislation 1850s-1970s". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 9 September 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

The Liquor Bill Section 104 of the Liquor Bill of 1928 Prohibiting Indians from entering licensed premises is withdrawn.

- "The Liquor Laws Amendment Bill comes into effect". South African History Online. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

Section 104 of the liquor bill was withdrawn, and Indians were once again allowed to enter licensed premises. Despite this, Africans were still not allowed to buy beer legally.

- Naidoo, Aneshree (12 August 2014). "Long reign of the South African shebeen queen". Media Club South Africa. Archived from the original on 27 March 2015. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

The Act had restricted profits for commercial brewers, and in 1962 the apartheid government caved under pressure from the industry and opened up sales to black South Africans. They could not drink in town – white areas – but they could now buy commercial beer at off-sales.

- Osada, Masako (2002). Sanctions and honorary whites : diplomatic policies and economic realities in relations between Japan and South Africa. Westport, Conn. [u.a.]: Greenwood Press. p. 163. ISBN 0313318778.

As of 14 May 1976, Chinese were treated as whites in terms of the Liquor Act.

- Brooks Spector, J (22 August 2013). "The UDF at 30: An organisation that shook Apartheid's foundation". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- Dubin, Steven C. (2012). Spearheading debate : culture wars & uneasy truces. Auckland Park, South Africa: Jacana. p. 225. ISBN 978-1431407378. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

...and the refusal of the Chinese to participate in the Tricameral Parliament.

- Harrison, David (1983). The White Tribe of Africa. University of California Press. pp. 279–281. ISBN 978-0-520-05066-2. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- "Premier Sun visits four African countries". Taiwan Review. 5 January 1980. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012.

- Measuring Worth, Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount - Consumer Price Index, retrieved on 26 January 2011

- Nyoka, Nation (3 October 2017). "Cosatu Apologises For Racial Insults Hurled at City of Johannesburg's Michael Sun". HuffPost UK. Retrieved 9 April 2019.

- Mashaba, Herman (5 April 2019). "When the liberators become the oppressors". politicsweb.co.za. Politicsweb. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

- Ho, Ufrieda (14 March 2019). "ANTI-CHINESE SENTIMENT: Hate speech case a message about racism, discrimination". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- Ho, Ufrieda (28 July 2022). "EQUALITY COURT: SA Chinese communities elated after winning hate speech case". Daily Maverick. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- "Chinese qualify for BEE". News24. 18 June 2008. Archived from the original on 9 January 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Mashego, Penelope (18 September 2015). "State defends BEE benefits for Chinese". BdLive. Archived from the original on 18 September 2015. Retrieved 20 December 2015.

- Y. J. Park and A. Y. Chen, "Intersections of race, class and power: Chinese in post-apartheid Free State", unpublished paper presented at the South African Sociological Association Congress, Stellenbosch, July 2008.

- Ho, Ufrieda (12 July 2013). "The arch angle on booming Chinatown". Mail and Guardian Online. Archived from the original on 14 July 2013. Retrieved 6 January 2016.

- "Cape Argus". Cape Argus. 11 April 2009. Retrieved 29 July 2010.

- Gastrow, Peter (2 February 2001). "Triad societies and Chinese organised crime in South Africa, Occasional Paper No 48" (PDF). ISS Africa. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

Further reading

- Yap, Melanie; Man, Dianne (1996). Colour, Confusion & Concessions: The History of the Chinese in South Africa. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-424-4.

- Park, Yoon Jung (2008). A Matter of Honour: Being Chinese in South Africa (Paperback ed.). Jacana Media (Pty) Ltd. ISBN 978-1-77009-568-7.

- Bright, Rachel (2013). Chinese Labour in South Africa, 1902-10: Race, Violence, and Global Spectacle. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-30377-5.