Pipa

The pipa, pípá, or p'i-p'a (Chinese: 琵琶) is a traditional Chinese musical instrument belonging to the plucked category of instruments. Sometimes called the "Chinese lute", the instrument has a pear-shaped wooden body with a varying number of frets ranging from 12 to 31. Another Chinese four-string plucked lute is the liuqin, which looks like a smaller version of the pipa. The pear-shaped instrument may have existed in China as early as the Han dynasty, and although historically the term pipa was once used to refer to a variety of plucked chordophones, its usage since the Song dynasty refers exclusively to the pear-shaped instrument.

A pipa from the late Ming dynasty | |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| Related instruments | |

| Pipa | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

"Pipa" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 琵琶 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

The pipa is one of the most popular Chinese instruments and has been played for almost two thousand years in China. Several related instruments are derived from the pipa, including the Japanese biwa and Korean bipa in East Asia, and the Vietnamese đàn tỳ bà in Southeast Asia. The Korean instrument is the only one of the three that is no longer widely used.

History

There are some confusions and disagreements about the origin of pipa. This may be due to the fact that the word pipa was used in ancient texts to describe a variety of plucked chordophones of the period from the Qin to the Tang dynasty, including the long-necked spiked lute and the short-necked lute, as well as the differing accounts given in these ancient texts. Traditional Chinese narrative prefers the story of the Han Chinese Princess Liu Xijun sent to marry a barbarian Wusun king during the Han dynasty, with the pipa being invented so she could play music on horseback to soothe her longings.[1][2] Modern researchers such as Laurence Picken, Shigeo Kishibe, and John Myers suggested a non-Chinese origin.[3][4][5]

The earliest mention of pipa in Chinese texts appeared late in the Han dynasty around the 2nd century AD.[6][7] According to Liu Xi's Eastern Han dynasty Dictionary of Names, the word pipa may have an onomatopoeic origin (the word being similar to the sounds the instrument makes),[6] although modern scholarship suggests a possible derivation from the Persian word "barbat", the two theories however are not necessarily mutually exclusive.[8][9] Liu Xi also stated that the instrument called pipa, though written differently (枇杷; pípá or 批把; pībǎ) in the earliest texts, originated from amongst the Hu people (a general term for non-Han people living to the north and west of ancient China).[6] Another Han dynasty text, Fengsu Tongyi, also indicates that, at that time, pipa was a recent arrival,[7] although later 3rd-century texts from the Jin dynasty suggest that pipa existed in China as early as the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC).[10] An instrument called xiantao (弦鼗), made by stretching strings over a small drum with handle, was said to have been played by labourers who constructed the Great Wall of China during the late Qin dynasty.[10][11] This may have given rise to the Qin pipa, an instrument with a straight neck and a round sound box, and evolved into ruan, an instrument named after Ruan Xian, one of the Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove and known for playing similar instrument.[12][13] Yet another term used in ancient text was Qinhanzi (秦漢子), perhaps similar to Qin pipa with a straight neck and a round body, but modern opinions differ on its precise form.[14][15][16]

The pear-shaped pipa is likely to have been introduced to China from Central Asia, Gandhara, and/or India.[2] Pear-shaped lutes have been depicted in Kusana sculptures from the 1st century AD.[17][18] The pear-shaped pipa may have been introduced during the Han dynasty and was referred to as Han pipa. However, depictions of the pear-shaped pipas in China only appeared after the Han dynasty during the Jin dynasty in the late 4th to early 5th century.[19] Pipa acquired a number of Chinese symbolisms during the Han dynasty - the instrument length of three feet five inches represents the three realms (heaven, earth, and man) and the five elements, while the four strings represent the four seasons.[7]

Depictions of the pear-shaped pipas appeared in abundance from the Southern and Northern dynasties onwards, and pipas from this time to the Tang dynasty were given various names, such as Hu pipa (胡琵琶), bent-neck pipa (曲項琵琶, quxiang pipa), some of these terms however may refer to the same pipa. Apart from the four-stringed pipa, other pear-shaped instruments introduced include the five-stringed, straight-necked, wuxian pipa (五弦琵琶, also known as Kuchean pipa (龜茲琵琶)),[20] a six-stringed version, as well as the two-stringed hulei (忽雷). From the 3rd century onwards, through the Sui and Tang dynasty, the pear-shaped pipas became increasingly popular in China. By the Song dynasty, the word pipa was used to refer exclusively to the four-stringed pear-shaped instrument.

The pipa reached a height of popularity during the Tang dynasty, and was a principal musical instrument in the imperial court. It may be played as a solo instrument or as part of the imperial orchestra for use in productions such as daqu (大曲, grand suites), an elaborate music and dance performance.[21] During this time, Persian and Kuchan performers and teachers were in demand in the capital, Chang'an (which had a large Persian community).[22] Some delicately carved pipas with beautiful inlaid patterns date from this period, with particularly fine examples preserved in the Shosoin Museum in Japan. It had close association with Buddhism and often appeared in mural and sculptural representations of musicians in Buddhist contexts.[21] One of the Buddhist Four Heavenly Kings, the Eastern Dhṛtarāṣṭra, is often depicted with a pipa.[23] Additionally, masses of pipa-playing Buddhist semi-deities are depicted in the wall paintings of the Mogao Caves near Dunhuang. The four and five-stringed pipas were especially popular during the Tang dynasty, and these instruments were introduced into Japan during the Tang dynasty as well as into other regions such as Korea and Vietnam. The five-stringed pipa however had fallen from use by the Song dynasty, although attempts have been made to revive this instrument in the early 21st century with a modernized five-string pipa modeled on the Tang dynasty instrument.[24]

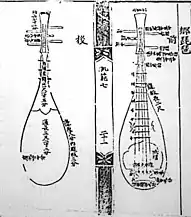

During the Song dynasty, pipa fell from favour at the imperial court, perhaps a result of the influence of neo-Confucian nativism as pipa had foreign associations.[25] However, it continued to be played as a folk instrument that also gained the interest of the literati.[21] The pipa underwent a number of changes over the centuries. By the Ming dynasty, fingers replaced plectrum as the popular technique for playing pipa, although finger-playing techniques existed as early as Tang.[26] Extra frets were added; the early instrument had 4 frets (相, xiāng) on the neck, but during the early Ming dynasty extra bamboo frets (品, pǐn) were affixed onto the soundboard, increasing the number of frets to around 10 and therefore the range of the instrument. The short neck of the Tang pipa also became more elongated.[25]

In the subsequent periods, the number of frets gradually increased,[27] from around 10 to 14 or 16 during the Qing dynasty, then to 19, 24, 29, and 30 in the 20th century. The 4 wedge-shaped frets on the neck became 6 during the 20th century. The 14- or 16-fret pipa had frets arranged in approximately equivalent to the western tone and semitone, starting at the nut, the intervals were T-S-S-S-T-S-S-S-T-T-3/4-3/4-T-T-3/4-3/4, (some frets produced a 3/4 tone or "neutral tone"). In the 1920s and 1930s, the number of frets was increased to 24, based on the 12 tone equal temperament scale, with all the intervals being semitones.[28] The traditional 16-fret pipa became less common, although it is still used in some regional styles such as the pipa in the southern genre of nanguan/nanyin. The horizontal playing position became the vertical (or near-vertical) position by the Qing dynasty, although in some regional genres such as nanguan the pipa is still held guitar fashion. During the 1950s, the use of metal strings in place of the traditional silk ones also resulted in a change in the sound of the pipa which became brighter and stronger.[2]

In Chinese literature

Early literary tradition in China, for example in a 3rd-century description by Fu Xuan, Ode to Pipa,[1][29] associates the Han pipa with the northern frontier, Wang Zhaojun and other princesses who were married to nomad rulers of the Wusun and Xiongnu peoples in what is now Mongolia, northern Xinjiang and Kazakhstan.[2][30] Wang Zhaojun in particular is frequently referenced with pipa in later literary works and lyrics, for example Ma Zhiyuan's play Autumn in the Palace of Han (漢宮秋), especially since the Song dynasty (although her story is often conflated with other women including Liu Xijun),[31][30] as well as in music pieces such as Zhaojun's Lament (昭君怨, also the title of a poem), and in paintings where she is often depicted holding a pipa.[30]

There are many references to pipa in Tang literary works, for example, in A Music Conservatory Miscellany Duan Anjie related many anecdotes associated with pipa.[32] The pipa is mentioned frequently in the Tang dynasty poetry, where it is often praised for its expressiveness, refinement and delicacy of tone, with poems dedicated to well-known players describing their performances.[33][34][35] A famous poem by Bai Juyi, "Pipa xing" (琵琶行), contains a description of a pipa performance during a chance encounter with a female pipa player on the Yangtze River:[36]

- 大絃嘈嘈如急雨

- 小絃切切如私語

- 嘈嘈切切錯雜彈

- 大珠小珠落玉盤

Thick strings clatter like splattering rain,

Fine strings murmur like whispered words,

Clattering and murmuring, meshing jumbled sounds,

Like pearls, big and small, falling on a platter of jade.

The encounter also inspired a poem by Yuan Zhen, Song of Pipa (琵琶歌). Another excerpt of figurative descriptions of a pipa music may be found in a eulogy for a pipa player, Lament for Shancai by Li Shen:[34]

- 銜花金鳳當承撥

- 轉腕攏弦促揮抹

- 花翻鳳嘯天上來

- 裴回滿殿飛春雪

On the plectrum, figure of a golden phoenix with flowers in its beak,

With turned wrist, he gathered the strings to pluck and strum faster.

The flowers fluttered, and from Heaven the phoenix trilled,

Lingering, filling the palace hall, spring snow flew.

During the Song dynasty, many of the literati and poets wrote ci verses, a form of poetry meant to be sung and accompanied by instruments such as pipa. They included Ouyang Xiu, Wang Anshi, and Su Shi. During the Yuan dynasty, the playwright Gao Ming wrote a play for nanxi opera called Pipa ji (琵琶記, or "Story of the Pipa"), a tale about an abandoned wife who set out to find her husband, surviving by playing the pipa. It is one of the most enduring work in Chinese theatre, and one that became a model for Ming dynasty drama as it was the favorite opera of the first Ming emperor.[37][38] The Ming collection of supernatural tales Fengshen Yanyi tells the story of Pipa Jing, a pipa spirit, but ghost stories involving pipa existed as early as the Jin dynasty, for example in the 4th century collection of tales Soushen Ji. Novels of the Ming and Qing dynasties such as Jin Ping Mei showed pipa performance to be a normal aspect of life in these periods at home (where the characters in the novels may be proficient in the instrument) as well as outside on the street or in pleasure houses.[25]

Playing and performance

The name "pipa" is made up of two Chinese syllables, "pí" (琵) and "pá" (琶). These, according to the Han dynasty text by Liu Xi, refer to the way the instrument is played – "pí" is to strike outward with the right hand, and "pá" is to pluck inward towards the palm of the hand.[6] The strings were played using a large plectrum in the Tang dynasty, a technique still used now for the Japanese biwa.[39] It has however been suggested that the long plectrum depicted in ancient paintings may have been used as a friction stick like a bow.[40] The plectrum has now been largely replaced by the fingernails of the right hand. The most basic technique, tantiao (彈挑), involves just the index finger and thumb (tan is striking with the index finger, tiao with the thumb). The fingers normally strike the strings of pipa in the opposite direction to the way a guitar is usually played, i.e. the fingers and thumb flick outward, unlike the guitar where the fingers and thumb normally pluck inward towards the palm of the hand. Plucking in the opposite direction to tan and tiao are called mo (抹) and gou (勾) respectively. When two strings are plucked at the same time with the index finger and thumb (i.e. the finger and thumb separate in one action), it is called fen (分), the reverse motion is called zhi (摭). A rapid strum is called sao (掃), and strumming in the reverse direction is called fu (拂). A distinctive sound of pipa is the tremolo produced by the lunzhi (輪指) technique which involves all the fingers and thumb of the right hand. It is however possible to produce the tremolo with just one or more fingers.

The left hand techniques are important for the expressiveness of pipa music. Techniques that produce vibrato, portamento, glissando, pizzicato, harmonics or artificial harmonics found in violin or guitar are also found in pipa. String-bending for example may be used to produce a glissando or portamento. Note however that the frets on all Chinese lutes are high so that the fingers and strings never touch the fingerboard in between the frets, this is different from many Western fretted instruments and allows for dramatic vibrato and other pitch changing effects.

In addition, there are a number of techniques that produce sound effects rather than musical notes, for example, striking the board of the pipa for a percussive sound, or strings-twisting while playing that produces a cymbal-like effect.

The strings are usually tuned to A2 D3 E3 A3 , although there are various other ways of tuning. Since the revolutions in Chinese instrument-making during the 20th century, the softer twisted silk strings of earlier times have been exchanged for nylon-wound steel strings, which are far too strong for human fingernails, so false nails are now used, constructed of plastic or tortoise-shell, and affixed to the fingertips with the player's choice of elastic tape. However, false nails made of horn existed as early as the Ming period when finger-picking became the popular technique for playing pipa.[25]

The pipa is held in a vertical or near-vertical position during performance, although in the early periods the instrument was held in the horizontal position or near-horizontal with the neck pointing slightly downwards, or upside down.[17][14] Starting about the 10th century, players began to hold the instrument "more upright", as the fingernail style became more important.[41] Through time, the neck was raised and by the Qing dynasty the instrument was mostly played upright.

Repertoire

Pipa has been played solo, or as part of a large ensemble or small group since the early times. Few pieces for pipa survived from the early periods, some, however, are preserved in Japan as part of togaku (Tang music) tradition. In the early 20th century, twenty-five pieces were found amongst 10th-century manuscripts in the Mogao caves near Dunhuang, most of these pieces however may have originated from the Tang dynasty. The scores were written in tablature form with no information on tuning given, there are therefore uncertainties in the reconstruction of the music as well as deciphering other symbols in the score.[42] Three Ming dynasty pieces were discovered in the High River Flows East (高河江東, Gaohe Jiangdong) collection dating from 1528 which are very similar to those performed today, such as "The Moon on High" (月兒高, Yue-er Gao). During the Qing dynasty, scores for pipa were collected in Thirteen Pieces for Strings.[43] During the Qing dynasty there originally two major schools of pipa—the Northern and Southern schools, and music scores for these two traditions were collected and published in the first mass-produced edition of solo pieces for pipa, now commonly known as the Hua Collection (華氏譜).[44] The collection was edited by Hua Qiuping (華秋萍, 1784–1859) and published in 1819 in three volumes.[45] The first volume contains 13 pieces from the Northern school, the second and third volumes contain 54 pieces from the Southern school. Famous pieces such as "Ambushed from Ten Sides", "The Warlord Takes Off His Armour", and "Flute and Drum at Sunset" were first described in this collection. The earliest-known piece in the collection may be "Eagle Seizing a Crane" (海青挐鶴) which was mentioned in a Yuan dynasty text.[46] Other collections from the Qing dynasty were compiled by Li Fangyuan (李芳園) and Ju Shilin (鞠士林), each representing different schools, and many of the pieces currently popular were described in these Qing collections. Further important collections were published in the 20th century.

The pipa pieces in the common repertoire can be categorized as wen (文, civil) or wu (武, martial), and da (大, large or suite) or xiao (小, small). The wen style is more lyrical and slower in tempo, with softer dynamic and subtler colour, and such pieces typically describe love, sorrow, and scenes of nature. Pieces in the Wu style are generally more rhythmic and faster, and often depict scenes of battles and are played in a vigorous fashion employing a variety of techniques and sound effects. The wu style was associated more with the Northern school while the wen style was more the Southern school. The da and xiao categories refer to the size of the piece – xiao pieces are small pieces normally containing only one section, while da pieces are large and usually contain multiple sections. The traditional pieces however often have a standard metrical length of 68 measures or beat,[47] and these may be joined together to form the larger pieces dagu.[48]

Famous solo pieces now performed include:

| Traditional Chinese | Simplified Chinese | Pinyin | English (translation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 十面埋伏 | 十面埋伏 | Shí Mìan Maífú | Ambushed from Ten Sides |

| 夕陽簫鼓/春江花月夜 | 夕阳箫鼓/春江花月夜 | Xīyáng Xīao Gǔ/Chūnjiāng Huā Yuèyè | Flute and Drum at Sunset / Flowery Moonlit River in Spring |

| 陽春白雪 | 阳春白雪 | Yángchūn Baíxuě | White Snow in Spring Sunlight |

| 龍船 | 龙船 | Lóngchuán | Dragon Boat |

| 彝族舞曲 | 彝族舞曲 | Yìzú Wúqǔ | Dance of the Yi People |

| 大浪淘沙 | 大浪淘沙 | Dàlàng Táo Shā | Big Waves Crashing on Sand |

| 昭君出塞 | 昭君出塞 | Zhàojūn Chū Saì | Zhaojun Outside the Frontier |

| 霸王卸甲 | 霸王卸甲 | Bàwáng Xiè Jiǎ | The Warlord Takes Off His Armour |

| 高山流水 | 高山流水 | Gāoshān Liúshuǐ | High Mountains Flowing Water |

| 月兒高 | 月儿高 | Yuè'er Gāo | Moon on High |

| 龜茲舞曲 | 龟兹舞曲 | Qiū cí wǔqǔ | Dance along the old Silk Road |

| 九連鈺 | 九连钰 | Jiǔ lián yù | Nine Jade Chains |

Most of the above are traditional compositions dating to the Qing dynasty or early 20th century, new pieces however are constantly being composed, and most of them follow a more Western structure. Examples of popular modern works composed after the 1950s are "Dance of the Yi People" and "Heroic Little Sisters of the Grassland" (草原英雄小姐妹). Non-traditional themes may be used in these new compositions and some may reflect the political landscape and demands at the time of composition, for example "Dance of the Yi People" which is based on traditional melodies of the Yi people, may be seen as part of the drive for national unity, while "Heroic Little Sisters of the Grassland" extols the virtue of those who served as model of exemplary behaviour in the People's commune.[49]

Schools

There are a number of different traditions with different styles of playing pipa in various regions of China, some of which then developed into schools. In the narrative traditions where the pipa is used as an accompaniment to narrative singing, there are the Suzhou tanci (蘇州彈詞), Sichuan qingyin (四川清音), and Northern quyi (北方曲藝) genres. Pipa is also an important component of regional chamber ensemble traditions such as Jiangnan sizhu, Teochew string music and Nanguan ensemble.[50] In Nanguan music, the pipa is still held in the near-horizontal position or guitar-fashion in the ancient manner instead of the vertical position normally used for solo playing in the present day.

There were originally two major schools of pipa during the Qing dynasty—the Northern (Zhili, 直隸派) and Southern (Zhejiang, 浙江派) schools—and from these emerged the five main schools associated with the solo tradition. Each school is associated with one or more collections of pipa music and named after its place of origin:

- Wuxi school (無錫派) – associated with the Hua Collection by Hua Qiuping, who studied with Wang Junxi (王君錫) of the Northern school and Chen Mufu (陳牧夫) of the Southern school, and may be considered a synthesis of these two schools of the Qing dynasty.[44] As the first published collection, the Hua Collection had considerable influence on later pipa players.

- Pudong school (浦東派) – associated with the Ju Collection (鞠氏譜) which is based on an 18th-century handwritten manuscript, Xianxu Youyin (閑敘幽音), by Ju Shilin.

- Pinghu school (平湖派) – associated with the Li Collection (李氏譜) first published in 1895; it was compiled by Li Fangyuan who came from a family of many generations of pipa players.[51]

- Chongming school (崇明派) – associated with Old Melodies of Yingzhou (瀛洲古調) compiled by Shen Zhaozhou (沈肇州, 1859–1930) in 1916.

- Shanghai or Wang school (汪派) – named after Wang Yuting (汪昱庭) who created this style of playing. It may be considered a synthesis of the other four schools especially the Pudong and Pinghu schools. Wang did not publish his notation book in his lifetime, although handwritten copies were passed on to his students.

These schools of the solo tradition emerged by students learning playing the pipa from a master, and each school has its own style, performance aesthetics, notation system, and may differ in their playing techniques.[52][53] Different schools have different repertoire in their music collection, and even though these schools share many of the same pieces in their repertoire, a same piece of music from the different schools may differ in their content. For example, a piece like "The Warlord Takes off His Armour" is made up of many sections, some of them metered and some with free meter, and greater freedom in interpretation is possible in the free meter sections. Different schools however can have sections added or removed, and may differ in the number of sections with free meter.[52] The music collections from the 19th century also used the gongche notation which provides only a skeletal melody and approximate rhythms sometimes with the occasional playing instructions given (such as tremolo or string-bending), and how this basic framework can become fully fleshed out during a performance may only be learnt by the students from the master. The same piece of music can therefore differ significantly when performed by students of different schools, with striking differences in interpretation, phrasing, tempo, dynamics, playing techniques, and ornamentations.

In more recent times, many pipa players, especially the younger ones, no longer identify themselves with any specific school. Modern notation systems, new compositions as well as recordings are now widely available and it is no longer crucial for a pipa players to learn from the master of any particular school to know how to play a score.

Performers

Historical

Pipa is commonly associated with Princess Liu Xijun and Wang Zhaojun of the Han dynasty, although the form of pipa they played in that period is unlikely to be pear-shaped as they are now usually depicted. Other early known players of pipa include General Xie Shang from the Jin dynasty who was described to have performed it with his leg raised.[54] The introduction of pipa from Central Asia also brought with it virtuoso performers from that region, for example Sujiva (蘇祇婆, Sujipo) from the Kingdom of Kucha during the Northern Zhou dynasty, Kang Kunlun (康崑崙) from Kangju, and Pei Luoer (裴洛兒) from Shule. Pei Luoer was known for pioneering finger-playing techniques,[26] while Sujiva was noted for the "Seven modes and seven tones", a musical modal theory from India.[55][56] (The heptatonic scale was used for a time afterwards in the imperial court due to Sujiva's influence until it was later abandoned). These players had considerable influence on the development of pipa playing in China. Of particular fame were the family of pipa players founded by Cao Poluomen (曹婆羅門) and who were active for many generations from the Northern Wei to Tang dynasty.[57]

Texts from Tang dynasty mentioned many renowned pipa players such as He Huaizhi (賀懷智), Lei Haiqing (雷海清), Li Guaner (李管兒), and Pei Xingnu (裴興奴).[35][58][59] Duan Anjie described the duel between the famous pipa player Kang Kunlun and the monk Duan Shanben (段善本) who was disguised as a girl, and told the story of Yang Zhi (楊志) who learned how to play the pipa secretly by listening to his aunt playing at night.[32] Celebrated performers of the Tang dynasty included three generations of the Cao family—Cao Bao (曹保), Cao Shancai (曹善才) and Cao Gang (曹剛),[60][61] whose performances were noted in literary works.[62][34]

During the Song dynasty, players mentioned in literary texts include Du Bin (杜彬).[63] From the Ming dynasty, famous pipa players include Zhong Xiuzhi (鍾秀之), Zhang Xiong (張雄, known for his playing of "Eagle Seizing Swan"), the blind Li Jinlou (李近樓), and Tang Yingzeng (湯應曾) who was known to have played a piece that may be an early version of "Ambushed from Ten Sides".[64]

During the Qing dynasty, apart from those of the various schools previously mentioned, there was Chen Zijing (陳子敬), a student of Ju Shilin and known as a noted player during the late Qing dynasty.

Modern era

_-_WOMEX_15%252C_2015.10.24_(1).JPG.webp)

In the 20th century, two of the most prominent pipa players were Sun Yude (孙裕德; 1904–1981) and Li Tingsong (李廷松; 1906–1976). Both were pupils of Wang Yuting (1872–1951), and both were active in establishing and promoting Guoyue ("national music"), which is a combination of traditional regional music and Western musical practices. Sun performed in the United States, Asia, and Europe, and in 1956 became deputy director of the Shanghai Chinese Orchestra. As well as being one of the leading pipa players of his generation, Li held many academic positions and also carried out research on pipa scales and temperament. Wei Zhongle (卫仲乐; 1903-1997) played many instruments, including the guqin. In the early 1950s, he founded the traditional instruments department at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. Players from the Wang and Pudong schools were the most active in performance and recording during the 20th century, less active was the Pinghu school whose players include Fan Boyan (樊伯炎). Other noted players of the early 20th century include Liu Tianhua, a student of Shen Zhaozhou of the Chongming school and who increased the number of frets on the pipa and changed to an equal-tempered tuning, and the blind player Abing from Wuxi.

Lin Shicheng (林石城; 1922–2006), born in Shanghai, began learning music under his father and was taught by Shen Haochu (沈浩初; 1899–1953), a leading player in the Pudong school style of pipa playing. He also qualified as a doctor of Chinese medicine. In 1956, after working for some years in Shanghai, Lin accepted a position at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing. Liu Dehai (1937–2020), also born in Shanghai, was a student of Lin Shicheng and in 1961 graduated from the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing. Liu also studied with other musicians and has developed a style that combines elements from several different schools. Ye Xuran (叶绪然), a student of Lin Shicheng and Wei Zhongle, was the Pipa Professor at the first Musical Conservatory of China, the Shanghai Conservatory of Music. He premiered the oldest Dunhuang Pipa Manuscript (the first interpretation made by Ye Dong) in Shanghai in the early 1980s.

Other prominent students of Lin Shicheng at the Central Conservatory of Music in Beijing include Liu Guilian (刘桂莲, born 1961), Gao Hong and Wu Man. Wu Man is probably the best known pipa player internationally, received the first-ever master's degree in pipa and won China's first National Academic Competition for Chinese Instruments. She lives in San Diego, California and works extensively with Chinese, cross-cultural, new music, and jazz groups. Shanghai-born Liu Guilian graduated from the Central Conservatory of Music and became the director of the Shanghai Pipa Society, and a member of the Chinese Musicians Association and Chinese National Orchestral Society, before immigrating to Canada. She now performs with Red Chamber and the Vancouver Chinese Music Ensemble. Gao Hong graduated from the Central Conservatory of Music and was the first to do a joint tour with Lin Shicheng in North America. They recorded the critically acclaimed CD "Eagle Seizing Swan" together.

Noted contemporary pipa players who work internationally include Min Xiao-Fen, Yang Jin(杨瑾), Zhou Yi, Qiu Xia He, Liu Fang, Cheng Yu, Jie Ma, Gao Hong, Yang Jing(楊靜), Yang Wei (杨惟),[65] Guan Yadong (管亚东), Jiang Ting (蔣婷), Tang Liangxing (湯良興),[66] and Lui Pui-Yuen (呂培原, brother of Lui Tsun-Yuen).[67] Some other notable pipa players in China include Yu Jia (俞嘉), Wu Yu Xia (吳玉霞), Fang Jinlong (方錦龍) and Zhao Cong (赵聪).

Use in contemporary classical music

In the late 20th century, largely through the efforts of Wu Man (in USA), Min Xiao-Fen (in USA), composer Yang Jing (in Europe) and other performers, Chinese and Western contemporary composers began to create new works for the pipa (both solo and in combination with chamber ensembles and orchestra). Most prominent among these are Minoru Miki, Thüring Bräm, YANG Jing, Terry Riley, Donald Reid Womack, Philip Glass, Lou Harrison, Tan Dun, Bright Sheng, Chen Yi, Zhou Long, Bun-Ching Lam, and Carl Stone.

Cheng Yu researched the old Tang dynasty five-stringed pipa in the early 2000s and developed a modern version of it for contemporary use.[68] It is very much the same as the modern pipa in construction save for being a bit wider to allow for the extra string and the reintroduction of the soundholes at the front. It has not caught on in China but in Korea (where she also did some of her research) the bipa was revived since then and the current versions are based on Chinese pipa, including one with five-strings. The 5 String Pipa is tuned like a Standard Pipa with the addition of an Extra Bass String tuned to an E2 (Same as the Guitar) which broadens the range (Tuning is E2, A2, D3, E3, A3). Jiaju Shen from The Either also plays an Electric 5 String Pipa/Guitar hybrid that has the Hardware from an Electric Guitar combined with the Pipa, built by an instrument maker named Tim Sway called "Electric Pipa 2.0".

Use in other genres

The pipa has also been used in rock music; the California-based band Incubus featured one, borrowed from guitarist Steve Vai, in their 2001 song "Aqueous Transmission," as played by the group's guitarist, Mike Einziger.[69] The Shanghai progressive/folk-rock band Cold Fairyland, which was formed in 2001, also use pipa (played by Lin Di), sometimes multi-tracking it in their recordings. Australian dark rock band The Eternal use the pipa in their song "Blood" as played by singer/guitarist Mark Kelson on their album Kartika. The artist Yang Jing plays pipa with a variety of groups.[70] The instrument is also played by musician Min Xiaofen in "I See Who You Are", a song from Björk's album Volta. Western performers of pipa include French musician Djang San, who integrated jazz and rock concepts to the instrument such as power chords and walking bass.[71]

Electric pipa

The electric pipa was first developed in the late 20th century by adding electric guitar–style magnetic pickups to a regular acoustic pipa, allowing the instrument to be amplified through an instrument amplifier or PA system.

A number of Western pipa players have experimented with amplified pipa. Brian Grimm placed the contact mic pickup on the face of the pipa and wedged under the bridge so he is able to plug into pedalboards, live computer performance rigs, and direct input (DI) to an audio interface for studio tracking.[72] In 2014, French zhongruan player and composer Djang San, created his own electric pipa and recorded an experimental album that puts the electric pipa at the center of music.[73] He was also the first musician to add a strap to the instrument, as he did for the zhongruan, allowing him to play the pipa and the zhongruan like a guitar.

In 2014, an industrial designer residing in the United States Xi Zheng (郑玺) designed and crafted an electric pipa – "E-pa" in New York. In 2015, pipa player Jiaju Shen (沈嘉琚) released a mini album composed and produced by Li Zong (宗立),[74] with E-pa music that has a strong Chinese flavor within a modern Western pop music mould.

Gallery

Sandstone carving, showing the typical way a pipa was held when played with plectrum in the early period. Northern Wei dynasty (386–534 AD).

Sandstone carving, showing the typical way a pipa was held when played with plectrum in the early period. Northern Wei dynasty (386–534 AD)..jpg.webp) Painted panel of the sarcophagus of Yü Hung, depicts one of the Persian or Sogdian figures playing pipa. 592 AD, Sui dynasty.

Painted panel of the sarcophagus of Yü Hung, depicts one of the Persian or Sogdian figures playing pipa. 592 AD, Sui dynasty.

.jpg.webp) Modern pipa player, with the pipa held in near upright position

Modern pipa player, with the pipa held in near upright position A pipa player playing with the pipa behind his back. Dunhuang, Mogao Caves.

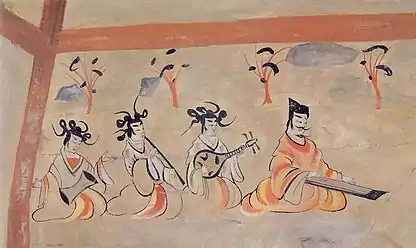

A pipa player playing with the pipa behind his back. Dunhuang, Mogao Caves. An early depiction of pipa player in a group of musicians. From the Dingjiazha Tomb No. 5, period of the Northern Wei (384-441 A.D.)

An early depiction of pipa player in a group of musicians. From the Dingjiazha Tomb No. 5, period of the Northern Wei (384-441 A.D.) A Song dynasty fresco depicts a female pipa player among a group of musicians

A Song dynasty fresco depicts a female pipa player among a group of musicians Group of female musician from the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907-960 AD)

Group of female musician from the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period (907-960 AD) A mural from a Yuan dynasty tomb found in Hengshan County, Shaanxi, showing a man playing the pipa

A mural from a Yuan dynasty tomb found in Hengshan County, Shaanxi, showing a man playing the pipa A Chinese woman playing a pipa, 1870

A Chinese woman playing a pipa, 1870 A group of Qing dynasty musicians from Fuzhou

A group of Qing dynasty musicians from Fuzhou

References

- Song Shu 《宋書·樂志一》 Book of Song quoting earlier work by Fu Xuan (傅玄), Ode to Pipa (琵琶賦). Original text: 琵琶,傅玄《琵琶賦》曰: 漢遣烏孫公主嫁昆彌,念其行路思慕,故使工人裁箏、築,為馬上之樂。欲從方俗語,故名曰琵琶,取其易傳於外國也。 Translation: Pipa – Fu Xuan's "Ode to Pipa" says: "The Han Emperor sent the Wusun princess to marry Kunmi, and being mindful of her thoughts and longings on her journey, instructed craftsmen to modify the Chinese zither Zheng and zhu to make an instrument tailored for playing on horseback. Therefore the common use of the old term pipa came about because it was transmitted to a foreign country." (Note that this passage contains a number of assertions whose veracity has been questioned by scholars.)

- Millward, James A. (10 June 2011). "The pipa: How a barbarian lute became a national symbol". Danwei. Archived from the original on 13 June 2011.

- Picken 1955, p. 40.

- Myers 1992, p. 5.

- Shigeo Kishibe (1940). "The Origin of the Pipa". Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan. 19: 269–304.

- Chinese Text Project – 《釋名·釋樂器》 Shiming by Liu Xi (劉熙)]. Original text: 枇杷,本出於胡中,馬上所鼓也。推手前曰枇,引手卻曰杷。象其鼓時,因以為名也。 Translation: Pipa, originated from amongst the Hu people, who played the instrument on horseback. Striking outward with the hand is called "pi", plucking inward is called "pa", sounds like when it is played, hence the name. (Note that this ancient way of writing pipa (枇杷) also means "loquat".)

- 應劭 -《風俗通義·聲音》 Fengsu Tongyi (Common Meanings in Customs) by Ying Shao. Original text: 批把: 謹按: 此近世樂家所作,不知誰也。以手批把,因以為名。長三尺五寸,法天地人與五行,四弦象四時。 Translation: Pipa, made by recent musicians, but maker unknown. Played "pi" and "pa" with the hand, it was thus named. Length of three feet five inches represents the Heaven, Earth, and Man, and the five elements, and the four strings represent the four seasons. (Note that this length of three feet five inches is equivalent to today's length of approximately two feet and seven inches or 0.8 meter.)

- Myers 1992, pp. 10–11.

- "Avaye Shayda - Kishibe's diffusionism theory on the Iranian Barbat and Chino-Japanese Pi' Pa'". Archived from the original on 12 September 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- 《琵琶錄》 Records of Pipa by Duan Anjie (段安節)] citing Du Zhi of Jin dynasty. Original text: 樂錄雲,琵琶本出於弦鼗。而杜摯以為秦之末世,苦於長城之役。百姓弦鼗而鼓之 Translation: According to Yuelu, pipa originated from xiantao. Du Zhi thought that towards the end of Qin dynasty, people who suffered as forced labourers on the Great Wall, played it using strings on a drum with handle. (Note that for the word xiantao, xian means string, tao means pellet drum, one common form of this drum is a flat round drum with a handle, a form that has some resemblance to Ruan.)

- 《舊唐書·音樂二》 Jiu Tangshu Old Book of Tang. Original text: 琵琶,四弦,漢樂也。初,秦長城之役,有鞀而鼓之者。 Translation: Pipa, four strings, comes from Han dynasty music. In the beginning, forced labourers on the Qin dynasty's Great Wall played it using a drum with handle.

- "The music of pipa". Archived from the original on 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2011-10-21.

- 杜佑 《通典》 Tongdian by Du You. Original text: 阮咸,亦秦琵琶也,而項長過於今制,列十有三柱。武太后時,蜀人蒯朗於古墓中得之,晉竹林七賢圖阮咸所彈與此類同,因謂之阮咸。 Translation: Ruan Xian, also called Qin pipa, although its neck was longer than today's instrument. It has 13 frets. During Empress Wu period, Kuailang from Sichuan found one in an ancient tomb. Ruan Xian of The Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove from the Jin dynasty was pictured playing this same kind of instrument, it was therefore named after Ruan Xian.

- 《舊唐書·音樂二》 Jiu Tangshu Old Book of Tang. Original text: 今《清樂》奏琵琶,俗謂之「秦漢子」,圓體修頸而小,疑是弦鞀之遺制。其他皆充上銳下,曲項,形制稍大,疑此是漢制。兼似兩制者,謂之「秦漢」,蓋謂通用秦、漢之法。 Translation: Today's "Qingyue" performance pipa, commonly called the Qinhanzi, has a round body with a small neck, and is suspected to be descended from Xiantao. The others are all shaped full on top and pointed at the bottom, neck bent, rather large, and suspected to be of Han dynasty origin. Being composite of two different constructions, it's called "Qinhan", as it is thought to use both Qin and Han methods. (Note that the description of the pear-shaped pipa as being "full on top and pointed at the bottom", an orientation that is inverted compared to modern instrument, and refers to the way pipa was often held in ancient times).

- John Myers (1992). "Chapter 1: A General history of the Pipa". The way of the pipa: structure and imagery in Chinese lute music. Kent State University Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-87338-455-5.

- 杜佑 《通典》 Tongdian by Du You citing Fu Xuan of Jin dynasty. Original text: 傅玄云:「體圓柄直,柱有十二。」 Translation: Fu Xuan said: "The body is round and the handle straight, and has twelve frets."

- Picken 1955, pp. 32–42.

- "Bracket with two musicians 100s, Pakistan, Gandhara, probably Butkara in Swat, Kushan Period (1st century-320)". The Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- Albert E. Dien (2007). Six Dynasties Civilization. Yale University Press. pp. 342–348. ISBN 978-0-300-07404-8.

- Myers 1992, p. 8.

- The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2. Routledge. 23 October 2008. pp. 1104–1105. ISBN 978-0415994040.

- See also The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T'ang Exotics, by Edward H. Schafer; University of California Press, 1963.

- "Diamond Gate". Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism. 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- "Cheng Yu : 5-string pipa". Ukchinesemusic.com. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- James A. Millward (June 2012). "Chordophone Culture in Two Early Modern Societies: "A Pipa-Vihuela" Duet". Journal of World History. 23 (2): 237–278. doi:10.1353/jwh.2012.0034. JSTOR 23320149. S2CID 145544440.

- 杜佑 《通典》 Tongdian by Du You Original text: 舊彈琵琶,皆用木撥彈之,大唐貞觀中始有手彈之法,今所謂搊琵琶者是也。《風俗通》所謂以手琵琶之,知乃非用撥之義,豈上代固有搊之者?手彈法,近代已廢,自裴洛兒始為之。 Translation: The olden ways of playing pipa all used a wooden plectrum for playing. During the reign of the Tang dynasty's Emperor Taizong, there began the use of a finger-playing technique, which is what's called plucked pipa today. What's referred to in Common Meanings in Customs as playing pipa by hand is thus understood to be played without plectrum, but how are we sure that there were those who played by plucking in this early period? The use of this technique has fallen away in recent times, but it was started by Pei Luoer. (Note that Pei Luoer is also known as Pei Shenfu (裴神符)).

- "琵琶小知识". Sohu.

- Lui, Tsun-Yuen; Wu, Ben (2001). "Pipa". Grove Music Online. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.45149.

- 杜佑 《通典》 Tongdian by Du You. A longer quote of Fu Xuan here.

- Stephen H. West; Wilt L. Idema, eds. (2010). Monks, Bandits, Lovers, and Immortals. Hackett Publishing Company. p. 158. ISBN 9781603844338.

- Ping Wang; Nicholas Morrow Williams, eds. (5 May 2015). Southern Identity and Southern Estrangement in Medieval Chinese Poetry. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 84–86. ISBN 978-9888139262.

- "樂府雜錄 - 维基文库,自由的图书馆". Zh.wikisource.org. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- 劉月珠 (April 2007). 唐人音樂詩研究: 以箜篌琵琶笛笳為主. 秀威出版. pp. 120–134. ISBN 9789866909412.

- 李紳 《悲善才》 Lament for Shancai by Li Shen. The name Shancai is also used to mean virtuoso or maestro in the Tang dynasty.

- 元稹 《琵琶歌》 Archived 2012-04-26 at the Wayback Machine Pipa Song by Yuan Zhen.

- 琵琶行 The "Pipa Song" by Bai Juyi, translation here

- Faye Chunfang Fei, ed. (2002). Chinese Theories of Theater and Performance from Confucius to the Present. University of Michigan Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0472089239.

- Jin Fu (2012). Chinese Theatre (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 447. ISBN 978-0521186667.

- "Pipa - A Chinese lute or guitar, its brief history, photos and music samples". Philmultic.com. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- Myers 1992, p. 14.

- "Pipa (琶) late 16th–early 17th century". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- A report on Chinese research into the Dunhuang music manuscripts Chen Yingshi, Musica Asiatica, 1991 ISBN 0-521-39050-8

- Xiansuo Shisan Tao (弦索十三套, later incorporated into Complete String Music 弦索俻套)

- This was first published as Nanbei Erpai Miben Pipapu Zhenzhuan (南北二派祕本琵琶譜真傳)

- John Myers (1992). The way of the pipa: structure and imagery in Chinese lute music. Kent State University Press. ISBN 0-87338-455-5.

- Luanjing Zayong 《灤京雜詠》 by Yang Yunfu (楊允孚) Original text: 為愛琵琶調有情,月髙未放酒杯停,新腔翻得凉州曲彈出天鵝避海青海。 《海青挐天鵝》新聲也。 This piece is however listed as "Eagle Seizing a Swan" (海青挐天鵝) here.

- John Myers (1992). "Chapter 3 – Musical structure in the Hua Collection". The way of the pipa: structure and imagery in Chinese lute music. Kent State University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 0-87338-455-5.

- Myers 1992, pp. 20–21.

- Bulag, Uradyn E. (July 1999). "Models and Moralities: The Parable of the Two "Heroic Little Sisters of the Grassland"". The China Journal. 42 (42): 21–41. doi:10.2307/2667639. JSTOR 2667639. S2CID 143684883.

- The Concise Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 2. Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Routledge. 2008. pp. 1104–1105. ISBN 978-0415994040.

- The Li Collection was published as Nanbei Pai Shisan Tao Daqu Pipa Xinpu 南北派十三套大曲琵琶新譜 in 1895.

- Lin, Esther E.-Shiun (20 April 1996). Pipa pai : concept, history and analysis of style. Open.library.ubc.ca (Thesis). doi:10.14288/1.0087817. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- "Comparison of Three Chinese Traditional Pipa Music Schools with the Aid of Sound Analysis" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- 劉義慶 《世說新語》 A New Account of the Tales of the World by Liu Yiqing. Original text: 桓大司馬曰:「諸君莫輕道,仁祖企腳北窗下彈琵琶,故自有天際真人想。」 Translation: Grand Marshal Huan said: "Gentlemen, do not disparage Renzu, he played the pipa under the north window with his leg raised, and thus evoked thoughts of an immortal in heaven." (Note that Renzu (仁祖) refers to Xie Shang.)

- 隋書 Book of Sui. Original text: 先是周武帝時,有龜茲人曰蘇祗婆,從突厥皇后入國,善胡琵琶。聽其所奏,一均之中間有七聲。因而問之,答雲:『父在西域,稱為知音。代相傳習,調有七種。』以其七調,勘校七聲,冥若合符 Translation: In the beginning, during the reign of Emperor Wu of Northern Zhou, there was a Kuchean named Sujiva, who came into the country with the Tu-jue empress and excelled in playing the hu pipa. Listening to what he played, within one scale there were seven notes. He was thus questioned about it, and he replied: "In the Western Region, my father was praised for his knowledge of music. As transmitted and practised through generations, there were seven kinds of mode." Taking his seven modes, and on investigating and comparing them with the seven notes, they fitted together and tallied well.

- Laurence E. R. Picken and Noel J. Nickson (2000). Music from the Tang court (PDF). Vol. 7. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-78084-1.

- 《舊唐書·音樂二》 Jiu Tangshu (Old Book of Tang) Original text: 後魏有曹婆羅門,受龜茲琵琶于商人,世傳其業。至孫妙達,尤為北齊高洋所重,常自擊胡鼓以和之。 Translation: During Later Wei there was Cao Poluomen, who was a trader in Kuchean pipa for whose craft he was famous. His grandchild Miaoda [曹妙达] in particular was highly regarded by Emperor Wenxuan of Northern Qi dynasty, who would often play the hu drum in accompaniment. (Note that Poluomen (or Bolomen) means Brahmin or Indian.)

- "琵琶錄 - 维基文库,自由的图书馆". Zh.wikisource.org. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- Note that some people claimed Pei Xingnu to be the female player described in the poem Pipa Xing, there is however no definitive proof of that claim.

- Duan Anjie – A Music Conservatory Miscellany (Yuefu zalu 樂府雜錄) Original text: – 貞元中有王芬、曹保,保其子善才其孫曹綱皆襲所藝。次有裴興奴,與綱同時。曹綱善運撥,若風雨,而不事扣弦,興奴長於攏撚,不撥稍軟。時人謂:「曹綱有右手,興奴有左手。」 Note that Shancai was used as a word to mean virtuoso or maestro during the Tang dynasty.

- 琵琶行 (Pipa xing) Original text: – 曲罷曾教善才伏,妝成每被秋娘妒。 Translation: Her art the admiration even of master Shancai, Her beauty the envy of all pretty girls.

- 劉禹錫 《曹剛》 Cao Gang by Liu Yuxi Original text: 大弦嘈囋小弦清,噴雪含風意思生。一聽曹剛彈薄媚,人生不合出京城。

- Houshan Shihua《後山詩話》 by Chen Shidao (陳師道), relating a story about Ouyang Xiu listening to Du Bin. Original text: 故公詩雲:座中醉客誰最賢?杜彬琵琶皮作弦。自從彬死世莫傳。 Translation: So Master (Ouyang Xiu) in his poem says: "Who amongst the drunken guests in their seats was the most worthy? It's Du Bin who played the pipa with animal hide for strings. Ever since Du Bin's death such skill is lost to the world".

- 《湯琵琶傳》 Original text: 而尤得意於《楚漢》一曲,當其兩軍決戰時,聲動天地,瓦屋若飛墜。徐而察之,有金聲、鼓聲、劍弩聲、人馬辟易聲。俄而無聲。久之,有怨而難明者,為楚歌聲;淒而壯者,為項王悲歌慷慨之聲、別姬聲;陷大澤,有追騎聲;至烏江,有項王自刎聲、餘騎蹂踐爭項王聲。

- "Wei Yang". Naxos.

- "Liang-xing Tang". National Endowment for the Arts.

- Chou, Oliver (6 December 2014). "Lui Pui-yuen, master of Chinese music, returns to perform once again". South China Morning Post.

- Cheng Yu : 5 string pipa (retrieved 13 July 2016

- "Incubus - Mike Einziger Guitar Gear Rig and Equipment". Uberproaudio.com. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- "[search page, albums featuring Yang Jing]". yangjingmusic.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2019.

- Pauline Bandelier (June 19, 2015). "La scène musicale alternative pékinoise vue par Jean Sébastien Héry (Djang San)". chine-info.com. Archived from the original on June 24, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2016.

- "BC GRIMM Experimental Acoustic-Electric Music EPK". Grim Musik. 26 January 2017.

- "Experimental Electric Pipa - 试验电琵琶, by Zhang Si'an (Djang San 张思安)". Djangsan.bandcamp.com. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- "Black Silk - Single by Jiaju Shen". Music.apple.com. 30 June 2015. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- "Celestial Pipa Musician". Smithsonian Museum.

HISTORICAL PERIOD(S) Five Dynasties to Yuan Dynasty, 10th to 13th century; MEDIUM Pigment on stucco; DIMENSIONS H x W: 38.2 x 36.2 cm (15 1/16 x 14 1/4 in); GEOGRAPHY China; CREDIT LINE Gift of Arthur M. Sackler; COLLECTION Arthur M. Sackler Gallery; ACCESSION NUMBER S1987.265

Bibliography

- Sadie, Stanley; Tyrrell, John, eds. (2001). New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2nd ed.). New York: Grove's Dictionaries. ISBN 1561592390.

- Millward, James A. (June 2012). "Chordophone Culture in Two Early Modern Societies: "A Pipa-Vihuela" Duet". Journal of World History. 23 (2): 237–278. doi:10.1353/jwh.2012.0034. JSTOR 23320149. S2CID 145544440.

- Myers, John (1992). The way of the pipa: structure and imagery in Chinese lute music. Kent State University Press. ISBN 9780873384551.

- Picken, Laurence (March 1955). "The Origin of the Short Lute". The Galpin Society Journal. 8: 32–42. doi:10.2307/842155. JSTOR 842155.

External links

- The Pipa on the Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art