Chinese postman problem

In graph theory, a branch of mathematics and computer science, Guan's route problem, the Chinese postman problem, postman tour or route inspection problem is to find a shortest closed path or circuit that visits every edge of an (connected) undirected graph at least once. When the graph has an Eulerian circuit (a closed walk that covers every edge once), that circuit is an optimal solution. Otherwise, the optimization problem is to find the smallest number of graph edges to duplicate (or the subset of edges with the minimum possible total weight) so that the resulting multigraph does have an Eulerian circuit.[1] It can be solved in polynomial time.[2]

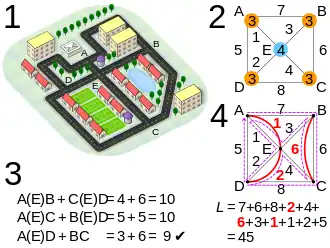

| 1 | Each street must be traversed at least once, starting and ending at the post office at A. |

|---|---|

| 2 | Four vertices with odd degree (orange) are found on its equivalent graph. |

| 3 | The pairing with the lowest total length is found. |

| 4 | After corresponding edges are added (red), the length of the Eulerian circuit is found. |

The problem was originally studied by the Chinese mathematician Kwan Mei-Ko in 1960, whose Chinese paper was translated into English in 1962.[3] The original name "Chinese postman problem" was coined in his honor; different sources credit the coinage either to Alan J. Goldman or Jack Edmonds, both of whom were at the U.S. National Bureau of Standards at the time.[4][5]

A generalization is to choose any set T of evenly many vertices that are to be joined by an edge set in the graph whose odd-degree vertices are precisely those of T. Such a set is called a T-join. This problem, the T-join problem, is also solvable in polynomial time by the same approach that solves the postman problem.

Undirected solution and T-joins

The undirected route inspection problem can be solved in polynomial time by an algorithm based on the concept of a T-join. Let T be a set of vertices in a graph. An edge set J is called a T-join if the collection of vertices that have an odd number of incident edges in J is exactly the set T. A T-join exists whenever every connected component of the graph contains an even number of vertices in T. The T-join problem is to find a T-join with the minimum possible number of edges or the minimum possible total weight.

For any T, a smallest T-join (when it exists) necessarily consists of paths that join the vertices of T in pairs. The paths will be such that the total length or total weight of all of them is as small as possible. In an optimal solution, no two of these paths will share any edge, but they may have shared vertices. A minimum T-join can be obtained by constructing a complete graph on the vertices of T, with edges that represent shortest paths in the given input graph, and then finding a minimum weight perfect matching in this complete graph. The edges of this matching represent paths in the original graph, whose union forms the desired T-join. Both constructing the complete graph, and then finding a matching in it, can be done in O(n3) computational steps.

For the route inspection problem, T should be chosen as the set of all odd-degree vertices. By the assumptions of the problem, the whole graph is connected (otherwise no tour exists), and by the handshaking lemma it has an even number of odd vertices, so a T-join always exists. Doubling the edges of a T-join causes the given graph to become an Eulerian multigraph (a connected graph in which every vertex has even degree), from which it follows that it has an Euler tour, a tour that visits each edge of the multigraph exactly once. This tour will be an optimal solution to the route inspection problem.[6][2]

Directed solution

On a directed graph, the same general ideas apply, but different techniques must be used. If the directed graph is Eulerian, one need only find an Euler cycle. If it is not, one must find T-joins, which in this case entails finding paths from vertices with an in-degree greater than their out-degree to those with an out-degree greater than their in-degree such that they would make in-degree of every vertex equal to its out-degree. This can be solved as an instance of the minimum-cost flow problem in which there is one unit of supply for every unit of excess in-degree, and one unit of demand for every unit of excess out-degree. As such it is solvable in O(|V|2|E|) time. A solution exists if and only if the given graph is strongly connected.[2][7]

Applications

Various combinatorial problems have been reduced to the Chinese Postman Problem, including finding a maximum cut in a planar graph and a minimum-mean length circuit in an undirected graph.[8]

Variants

A few variants of the Chinese Postman Problem have been studied and shown to be NP-complete.[9]

- The windy postman problem is a variant of the route inspection problem in which the input is an undirected graph, but where each edge may have a different cost for traversing it in one direction than for traversing it in the other direction. In contrast to the solutions for directed and undirected graphs, it is NP-complete.[10][11]

- The Mixed Chinese postman problem: for this problem, some of the edges may be directed and can therefore only be visited from one direction. When the problem calls for a minimal traversal of a digraph (or multidigraph) it is known as the "New York Street Sweeper problem."[12]

- The k-Chinese postman problem: find k cycles all starting at a designated location such that each edge is traversed by at least one cycle. The goal is to minimize the cost of the most expensive cycle.

- The "Rural Postman Problem": solve the problem with some edges not required.[11]

References

- Roberts, Fred S.; Tesman, Barry (2009), Applied Combinatorics (2nd ed.), CRC Press, pp. 640–642, ISBN 9781420099829

- Edmonds, J.; Johnson, E.L. (1973), "Matching Euler tours and the Chinese postman problem" (PDF), Mathematical Programming, 5: 88–124, doi:10.1007/bf01580113, S2CID 15249924

- Kwan, Mei-ko (1960), "Graphic programming using odd or even points", Acta Mathematica Sinica (in Chinese), 10: 263–266, MR 0162630. Translated in Chinese Mathematics 1: 273–277, 1962.

- Pieterse, Vreda; Black, Paul E., eds. (September 2, 2014), "Chinese postman problem", Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures, National Institute of Standards and Technology, retrieved 2016-04-26

- Grötschel, Martin; Yuan, Ya-xiang (2012), "Euler, Mei-Ko Kwan, Königsberg, and a Chinese postman" (PDF), Optimization stories: 21st International Symposium on Mathematical Programming, Berlin, August 19–24, 2012, Documenta Mathematica, Extra: 43–50, MR 2991468.

- Lawler, E.L. (1976), Combinatorial Optimization: Networks and Matroids, Holt, Rinehart and Winston

- Eiselt, H. A.; Gendeaeu, Michel; Laporte, Gilbert (1995), "Arc Routing Problems, Part 1: The Chinese Postman Problem", Operations Research, 43 (2): 231–242, doi:10.1287/opre.43.2.231

- A. Schrijver, Combinatorial Optimization, Polyhedra and Efficiency, Volume A, Springer. (2002).

- Crescenzi, P.; Kann, V.; Halldórsson, M.; Karpinski, M.; Woeginger, G, A compendium of NP optimization problems, KTH NADA, Stockholm, retrieved 2008-10-22

- Guan, Meigu (1984), "On the windy postman problem", Discrete Applied Mathematics, 9 (1): 41–46, doi:10.1016/0166-218X(84)90089-1, MR 0754427.

- Lenstra, J.K.; Rinnooy Kan, A.H.G. (1981), "Complexity of vehicle routing and scheduling problems" (PDF), Networks, 11 (2): 221–227, doi:10.1002/net.3230110211

- Roberts, Fred S.; Tesman, Barry (2009), Applied Combinatorics (2nd ed.), CRC Press, pp. 642–645, ISBN 9781420099829

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Chinese Postman Problem", MathWorld

Media related to Route inspection problem at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Route inspection problem at Wikimedia Commons