Quercus muehlenbergii

Quercus muehlenbergii, the chinquapin (or chinkapin) oak, is a deciduous species of tree in the white oak group (Quercus sect. Quercus). The species was often called Quercus acuminata in older literature. Quercus muehlenbergii (often misspelled as muhlenbergii) is native to eastern and central North America. It ranges from Vermont to Minnesota, south to the Florida panhandle, and west to New Mexico in the United States.[5] In Canada it is only found in southern Ontario, and in Mexico it ranges from Coahuila south to Hidalgo.[4]

| Quercus muehlenbergii | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Fagales |

| Family: | Fagaceae |

| Genus: | Quercus |

| Subgenus: | Quercus subg. Quercus |

| Section: | Quercus sect. Quercus |

| Species: | Q. muehlenbergii |

| Binomial name | |

| Quercus muehlenbergii | |

| |

| Natural range | |

| Synonyms[2][3] | |

|

List

| |

Description

Chinquapin oak is monoecious in flowering habit; flowers emerge in April to late May or early June. The staminate flowers are borne in catkins that develop from the leaf axils of the previous year, and the pistillate flowers develop from the axils of the current year's leaves. The fruit, an acorn or nut, is borne singly or in pairs, matures in one year, and ripens in September or October. About half of the acorn is enclosed in a thin cup and is chestnut brown to nearly black.[4]

Chinquapin oak is closely related to the smaller but generally similar dwarf chinquapin oak (Quercus prinoides). Chinquapin oak is usually a tree, but occasionally shrubby, while dwarf chinquapin oak is a low-growing, clone-forming shrub. The two species generally occur in different habitats: chinquapin oak is typically found on calcareous soils and rocky slopes, while dwarf chinquapin oak is usually found on acidic substrates, primarily sand or sandy soils, and also dry shales.[4][6]

Chinquapin oak is also sometimes confused with the related chestnut oak (Quercus montana), which it closely resembles. However, unlike the pointed teeth on the leaves of the chinquapin oak, chestnut oak leaves generally have rounded teeth. The two species have contrasting kinds of bark: chinquapin oak has a gray, flaky bark very similar to that of white oak (Q. alba) but with a more yellow-brown cast to it (hence the occasional name yellow oak for this species), while chestnut oak has dark, solid, deeply ridged bark. The chinquapin oak also has smaller acorns than the chestnut oak or another similar species, the swamp chestnut oak (Q. michauxii), which have some of the largest acorns of any oaks.[4]

Key characteristics of Quercus muehlenbergii include:[7]

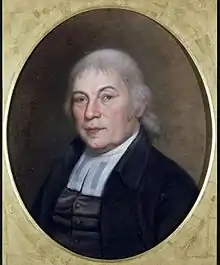

Taxonomy

Q. muehlenbergii is generally regarded as a distinct species from the similar-appearing chestnut oak (Q. montana). The tree's scientific name honors Gotthilf Heinrich Ernst Muhlenberg (1753–1815), a Lutheran pastor and amateur botanist in Pennsylvania. In publishing the name Quercus mühlenbergii, German-American botanist George Engelmann mistakenly used an umlaut in spelling Muhlenberg's name, even though Pennsylvania-born Muhlenberg himself did not use an umlaut in his name. Under the modern rules of botanical nomenclature, umlauts are transliterated, with ü becoming ue, hence Engelmann's Quercus mühlenbergii is now presented as Quercus muehlenbergii. In lack of evidence that Engelmann's use of the umlaut was an unintended error, and hence correctable, the muehlenbergii spelling is considered correct, although the more appropriate orthographic variant Quercus muhlenbergii is often seen.[8][9]

The low-growing, cloning Q. prinoides (dwarf chinquapin oak) is similar to Q. muehlenbergii and has been confused with it in the past, but is now generally accepted as a distinct species.[6] If the two are considered to be conspecific, the earlier-published name Quercus prinoides has priority over Q. muehlenbergii, and the larger chinquapin oak can then be classified as Quercus prinoides var. acuminata, with the dwarf chinquapin oak being Quercus prinoides var. prinoides. Q. prinoides was named and described by the German botanist Karl (Carl) Ludwig Willdenow in 1801, in a German journal article by Muhlenberg.[4]

Ecology

Soil and topography

Chinquapin oak is generally found on well-drained upland soils derived from limestone or where limestone outcrops occur. Occasionally it is found on well-drained limestone soils along streams. Chinquapin oak is generally found on soils that are weakly acid (pH about 6.5) to alkaline (above pH 7.0). It grows on both northerly and southerly aspects but is more common on the warmer southerly aspects. It is absent or rare at high elevations in the Appalachians.[10][11]

Associated cover

It is rarely a predominant tree, but it grows in association with many other species. It is a component of the forest cover type White Oak-Black Oak-Northern Red Oak (Society of American Foresters Type 52) and the Post Oak-Blackjack Oak (Type 40) (2).

It grows in association with white oak (Quercus alba), black oak (Q. velutina), northern red oak (Q. rubra), scarlet oak (Q. coccinea), sugar maple (Acer saccharum), red maple (A. rubrum), hickories (Carya spp.), black cherry (Prunus serotina), cucumbertree (Magnolia acuminata), white ash (Fraxinus americana), American basswood (Tilia americana), black walnut (Juglans nigra), butternut (J. cinerea), and yellow-poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera). American beech (Fagus grandifolia), shortleaf pine (Pinus echinata), pitch pine (P. rigida), Virginia pine (P. virginiana), Ozark chinquapin (Castanea ozarkensis), eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), bluejack oak (Quercus incana), southern red oak (Q. falcata), blackgum (Nyssa sylvatica), and winged elm (Ulmus alata) also grow in association with chinquapin oak. In the Missouri Ozarks a redcedar-chinquapin oak association has been described.[12]

The most common small tree and shrub species found in association with chinquapin oak include flowering dogwood (Cornus florida), sassafras (Sassafras albidum), sourwood (Oxydendrum arboreum), eastern hophornbeam (Ostrya virginiana), Vaccinium spp., Viburnum spp., hawthorns (Crataegus spp.), and sumacs (Rhus spp.). The most common woody vines are wild grape (Vitis spp.) and greenbrier (Smilax spp.).

Reaction to competition

Chinquapin oak is classified as intolerant of shade. It withstands moderate shading when young but becomes more intolerant of shade with age. It is regarded as a climax species on dry, drought prone soils, especially those of limestone origin. On more moist sites it is subclimax to climax. It is often found as a component of the climax vegetation in stands on mesic sites with limestone soils. However, many oak-hickory stands on moist sites that contain chinquapin oak are succeeded by a climax forest including beech, maple, and ash.[13]

Diseases and pests

Severe wildfire kills chinquapin oak saplings and small pole-size trees, but these often resprout. However, fire scars serve as entry points for decay-causing fungi, and the resulting decay can cause serious losses.

Oak wilt (Bretziella fagacearum), a vascular disease, attacks chinquapin oak and usually kills the tree within two to four years. Other diseases that attack chinquapin oak include the cankers Strumella coryneoidea and Nectria galligena, shoestring root rot (Armillarea mellea), anthracnose (Gnomonia veneta), and leaf blister (Taphrina spp.).

The most serious defoliating insects that attack chinquapin oak are the gypsy moth (Lymantria dispar), the orangestriped oakworm (Anisota senatoria), and the variable oakleaf caterpillar (Heterocampa manteo). Insects that bore into the bole and seriously degrade the products cut from infested trees include the carpenterworm (Prionoyxstus robiniae), little carpenterworm (P. macmurtrei), white oak borer (Goes tigrinus), Columbian timber beetle (Corthylus columbianus), oak timberworm (Arrhenodes minutus), and twolined chestnut borer (Agrilus bilineatus). The acorn weevils (Curculio spp.), larvae of moths (Valentinia glandulella and Melissopus latiferreanus), and gall forming cynipids (Callirhytis spp.) feed on the acorns.

Uses

Like that of other white oak species, the wood of the chinquapin oak is a durable hardwood prized for many types of construction.[14]

The chinquapin oak is especially known for its sweet and palatable acorns. The nuts contained inside of the thin shell are among the sweetest of any oak, with an excellent taste even when eaten raw, providing an excellent source of food for both wildlife and people. The acorns are eaten by squirrels, mice, voles, chipmunks, deer, turkey, and other birds.[15][16]

References

- Kenny, L.; Wenzell, K.; Jerome, D. (2017). "Quercus muehlenbergii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T194202A111279204. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-2.RLTS.T194202A111279204.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- "Quercus muehlenbergii". Tropicos. Missouri Botanical Garden.

- "Quercus muehlenbergii". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew – via The Plant List. Note that this website has been superseded by World Flora Online

- Nixon, Kevin C. (1997). "Quercus muehlenbergii". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 3. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- "Quercus muehlenbergii". County-level distribution map from the North American Plant Atlas (NAPA). Biota of North America Program (BONAP). 2014.

- Nixon, Kevin C. (1997). "Quercus prinoides". In Flora of North America Editorial Committee (ed.). Flora of North America North of Mexico (FNA). Vol. 3. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press. Retrieved 8 October 2011 – via eFloras.org, Missouri Botanical Garden, St. Louis, MO & Harvard University Herbaria, Cambridge, MA.

- Barnes, B. V.; Wagner Jr., W. H. (2008). "Michigan Trees". University of Michigan Press.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - "Quercus muehlenbergii". NatureServe Explorer. NatureServe. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- Kendig, James W. (1979). "NOMENCLATURAL HISTORY OF QUERCUS MUEHLENBERGII". Bartonia. pp. 45–48.

- "Quercus muehlenbergii Engelm". www.srs.fs.usda.gov. Retrieved 2023-08-31.

- Sander, Ivan. "Quercus muehlenbergii Engelm" (PDF). Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- Scott, A. O. (2010-06-10). "Where Life Is Cold, and Kin Are Cruel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-05-06.

- "Quercus macrocarpa". www.fs.usda.gov. Retrieved 2022-10-19.

- "Chinkapin Oak". Department of Horticulture, College of Agriculture, Food and Environment, University of Kentucky. Retrieved 2017-10-05.

- "Chinquapin Oak – a NICE! good looking shade tree". The Boerne Chapter of NPSOT (Native Plant Society of Texas). 9 May 2011.

- Sander, Ivan L. (1990). "Quercus muehlenbergii". In Burns, Russell M.; Honkala, Barbara H. (eds.). Hardwoods. Silvics of North America. Washington, D.C.: United States Forest Service (USFS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Vol. 2 – via Southern Research Station.