Choe Je-u

Choe Je-u, who used the pen name Su-un (18 December 1824 – 15 April 1864), was the founder of Donghak,[1] a Korean religious movement which was empathetic to the hardships of the minjung (the marginalized people of Korea), opposed Catholicism and its association with western imperialism and offered an alternative to orthodox Neo-Confucianism.

| Choe Je-u | |

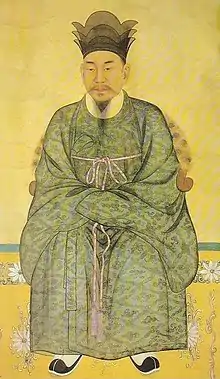

Portrait of Choe Je-u | |

| Korean name | |

|---|---|

| Hangul | 최제우 |

| Hanja | 崔濟愚 |

| Revised Romanization | Choe Je-u |

| McCune–Reischauer | Ch'oe Che-u |

| Art name | |

| Hangul | 수운 |

| Hanja | 水雲 |

| Revised Romanization | Su-un |

| McCune–Reischauer | Su-un |

He combined Korean shamanism, Daoism, Buddhism and spiritual Neo-Confucianism in an “original school of thought”[2] that valued rebellion and anti-government thought until 1864.[3] He did not have a concrete nationalistic or anti-feudal agenda,[4] rather: “His vision was religious, and his mission was to remind his countrymen that strength lay in reviving traditional values.”[5] Nevertheless, Joseon authorities confused his teachings with Catholicism; [6] and he was executed in 1864 for allegedly preaching heretical and dangerous teachings.[7]

His birth-name was Choe Je-seon ("save and proclaim"). During his childhood, he was also called Bok-sul ("blissfully happy"). He took the name Je-u ("saviour of the ignorant") in 1859. His disciples called him Su-un ("water cloud"), which was the name he used for his writings, and also called him Daesinsa, the great teacher.[8] His pen name Su-un is used hereafter.

Life

Su-un was born into an aristocratic (yangban) family on 18 December 1824 (the 28th day of the 10th month) at Kajong-ni, a village near Gyeongju, the ex-capital of Silla and now a city in the south-eastern province of Gyeongsang.[8]

Silla which was the first unified dynasty on the peninsula and had a strong scholarly and Buddhist tradition. One of his ancestors was a famous scholar who had served in the Tang emperor court of China and had returned Silla. One of his contemporaries called him the "Confucius of Korea. In addition, he was considered the founder of Daoism on the peninsula.[9]

His father Choe Ok was a scholar who had failed to obtain a post in the government, his clan not being in favor with those then in power. He had reached the age of sixty and had been married and widowed twice without gaining a son. He adopted a nephew in order to preserve his own line before marrying a widow named Han. Su-un was the result of this final union, but he was considered illegitimate in the Neo-Confucian system: the children of a widow who had remarried occupied a low position in the social hierarchy and could not, for example, take the civil examinations necessary to become a bureaucrat.[10] Despite this he received a good education. However, Choe Ok certainly provided his son with a strong education, in Neo-Confucianism and perhaps other doctrinal traditions such as Daoism.[11]

His mother died when he was six years old, and his father when he was sixteen.[12] He married in his teens to Madam Park of Ulsan.[13] He led an itinerant life before finally settling with his family in Ulsan in 1854. Although educated in Confucianism, he partook of Buddhist practices, rituals, and beliefs, including interacting with monks, visiting temples, and abstaining from meat. [14] In 1856, he began a 49-day retreat in the Buddhist monastery of Naewon-sa, but had to leave on the 47th day to attend the funeral of his uncle. The next year he managed to complete the 49 days at Cheok-myeol Caves, but did not find the experience spiritually fulfilling.[15]

In 1858 he lost his house and all effects in bankruptcy, and he returned with his family to the paternal household in 1859. While there, he spent his time in prayer and meditation. The discrimination and economic hardships he faced seemed to serve as stimulation for his "revolutionary" ideas. He later wrote that he lamented the "sickness in society since the age of ten, so much so that he felt that he was living in a "dark age".[16] Su-un felt he was called to address the root cause of the "dark age" which he considered to be inner spiritual depletion and social corruption. He considered the enormous western imperial power was due to a combination of military and spiritual power. It seemed that Korean spiritual traditions, Confucianism in particular, had lost their power. In fact, Confucianism was a tool of the upper classes to maintain the status quo.[16]

According to his own account, he was greatly concerned by the public disorder in Korea, the encroachments of Christianity, and the domination of East Asia by Western powers, which seemed to indicate that divine favor had passed into the hands of foreigners:

- A strange rumour spread through the land that Westerners had discovered the truth and that there was nothing that they could not do. Nothing could stand before their military power. Even China was being destroyed. Will our country too suffer the same fate? Their Way is called Western Learning, the religion of Cheonju, their doctrine, the Holy Teaching. Is it possible that they know the Heavenly Order and have received the Heavenly Mandate?[17]

Religious activities

On 25 May 1860 (the 5th day of the 4th month, lunar calendar) he experienced his first revelation, the kaepyeok, at his father's Yongdam Pavilion on Mount Gumi, several kilometres northwest of Gyeongju: a direct encounter with Sangje ("Lord of Heaven"). During the encounter, Su-un received two gifts, a talisman (the Yeongbu) and an incantation (the Jumun).[18] The talisman was a symbol drawn on paper which was to be burned, mixed in water and ingested. The incantation was to be chanted repeatedly. In following these rituals physical and spiritual health could be restored. According to Beirne the meditative drawing and consumption of the Yeongbu was "a visible sign and celebration of the intimate union between the Lord of Heaven and the practitioner, the effect of which invigorates both body and spirit."[19]

The use of the incantation ritual matured over time. Initially the emphasis was on restoration of physical health. A later variant of the incantation put more emphasis on spiritual enlightenment.[20] With respect to spiritual enlightenment, the purpose of reciting the incantation was to bring about the presence of the Lord of Heaven on each occasion within the believer or to effect an awareness of the indwelling of the Lord of Heaven through practice, repetition and refinement of the spirit. Both of these interpretations seem to be implied in his writings.[21]

Su-un was instructed by God to spread his teaching to humankind. He threw himself into three years of proselytising. His initial writings were in vernacular Korean and were intended for his family. They were composed as poems or songs in a four-beat gasa style, which lends itself to memorization. After a year of meditation, he wrote essays in classical Chinese expounding on his ideas. However, he continued to write in vernacular Korean, which increased his popularity among commoners and women who could not read Chinese. He called his doctrine Donghak ("eastern learning") to distinguish it from the Seohak ("western learning") of the Catholics.[22] Eastern Learning can be understood as “Korean Learning”. This follows from the fact that Joseon Korea was known as the Eastern Country due to its location east of China.[23]

Donghak was largely a combination of Korean shamanism, Daoism, Buddhism and Neo-Confucianism. The evidence of the latter is clearly discernible only from the middle stage of Su-un's thought onward, an indication of his evolving theology.[24] However, according to So Jeong Park, Donghak is not merely a “syncretism of Asian philosophical traditions seasoned with Korean aspirations for modernization”, rather it was a “novel or original school of thought”.[2] On the other hand, an earlier evaluation by Susan Shin emphasized the continuity of Donghak with a spiritual branch of Neo-Confucianism exemplified by the teaching of Wang Yangming.[25]

Su-un's concept of the singular God (Cheonju/Sangje) or God/Heaven, seemed to reflect that of Catholicism, although it differed with respect to ideas of transience and immanence.[26][27] Also, like Catholicism, Donghak was communal and egalitarian. Orthodox Neo-Confucians in power at the time of its founding viewed Catholicism and Donghak as threats in two ways. First, if there are many gods, no single god had the power to challenge the existing Confucian order. However, a believer in an omniscient God or God/Heaven might put His demands above those of a human king. Believers would also be expected to shun other gods and thus hold themselves apart from those with less dogmatic beliefs and thereby disrupting the harmony of the kingdom. Second, Catholicism and Donghak practiced group rituals which were beyond the control of the government, furthermore they demanded the right to practice those rituals. In other words, they engendered a concept of religious freedom which was new to Korea.[28] Although Su-un attempted to distinguish Donghak and Catholicism, government officials confused the two and both were suppressed.[6]

According to Susan Shin, He learned that he was suspected of Catholicism and from June 1861 to March 1862 he had to take refuge in Jeolla province to avoid arrest, spending the winter in a Buddhist temple in Namwon.[29] While there he wrote important parts of his scripture, including Discussions of Learning, Song of Encouraging Learning and Poem on Spiritual Training.[7]

Estimates of the number of his followers prior to his arrest in 1863 ranged from hundreds to tens of thousands and he became famous throughout the peninsula. He had established assemblies in at least twelve villages and towns. These were located primarily the southeastern part of Joseon Korea.[30]

Su-un was arrested shortly before 10 December 1863 for allegedly preaching heretical and dangerous teachings. He was tried, found guilty on 5 April 1864, and beheaded on 15 April 1864 (the 10th day of the 3rd month) at Daegu,[31] at the place today marked by his statue. His grave is in a park at Yugok-dong, a few kilometers north of Ulsan.

Assumed political agenda

Some Donghak scholars have assumed that it had a nationalistic agenda. However, according to Susan Shin: [Su-un] did not deal concretely with the problems of integrating Korea into the international order. His vision was religious, and his mission was to remind his countrymen that strength lay in reviving traditional values.”[5] Donghak's goal was protection of the people which could be considered patriotic, but that does not imply nationalism. It was simply a network/frame of followers of Su-un's religious views and rituals. Later leaders in the early 20th century did aspire to a modern Korean state primarily through education. However, these aspirations eventually led to violent confrontations with Japanese authorities.[4] [32]

The peasant revolts in Gyeongsang in 1862 were contemporaneous with Su-un's ministry, however detailed analysis of the circumstances revealed that these were in response to corruption by local officials. There was no mention of religious influence, and an anti-feudalistic agenda was discounted.[33]

On the other hand, Joseon Korean authorities did misconstrue Donghak intentions. A government statement warned: "This thing called Donghak inherited all the methods of Western Learning, whereas it only changed its name to confuse and incite ignorant ears. If it is not punished and settled in its infancy according to the laws of the country, then how do we know that it will not gradually turn into another Yellow Turban or White Lotus?”[6] The Taiping Rebellion in China was also in progress as Donghak was founded and by coincidence its leader Hong Xiuquan died on June 1, 1864, shortly after Su-un.[34]

Legacy

After his death, the movement was continued by Choe Sihyeong (Haewol, 1827–1898). The works of Su-un were collected in two volumes, The Bible of the Donghak Doctrine (in Korean-Chinese, 1880) and The Hymns of Dragon Lake (in Korean, 1881).[35]

In 1894, the brutally suppressed Donghak Peasant Revolution, led by Jeon Bongjun (1854–1895), set the stage for the First Sino-Japanese War, which placed Korea under Japanese control.[36] Haewol evaded capture for four years but was finally executed in 1898. In the wake of this disaster, the movement was drastically reorganized by Son Byong-Hi (Uiam, 1861–1922), who modernized Donghak according to western standards, which he learned during a five-year exile in Japan (under an assumed name).[37] However, when one of his chief lieutenants advocated annexation of Korea by Japan, Uiam excommunicated him and renamed Donghak as Cheondogyo in 1905.[38] Cheondogyo was tolerated by Japanese authorities, although it was considered a pseudo-religion.[39] After Japan annexed Korea, Cheondogyo and Protestant leaders protested, and they were a major factor in the March 1st Movement of 1919 in the initial peaceful stage.[40] Although the March First Movement failed members of Cheondogyo remained active in many social, political, and cultural organizations during the remainder of the colonial period. However, today only a small remnant remains in South Korea. In North Korea it is simply a nominal component of the Workers Party.[41] Nevertheless, scholars such as Sr. Myongsook Moon considered the Donghak worldview and ethics to be particularly relevant in the 21st century.[42]

Su-un life was the subject of Stanley Park's 2011 film The Passion of a Man named Choe Che-u (동학, 수운 최제우).

Works

His works were proscribed and burnt after his execution, but two canonical books, one of prose and one of poetry, were compiled and published later by Choe Sihyeong:

See also

Sources

- Ahn, Sang Jin Continuity and Transformation Religious Synthesis in East Asia. Asian Thought and Culture, Vol. 41. Peter Lang. 2001. ISBN 9780820448947.

- Bae, Byeongdae (2020). "Comparative and historical analysis of early Donghak: cross-religious dialogue between Confucianism and Catholicism in 19th-Century Korea". Religions. 11 (608): 608. doi:10.3390/rel11110608.

- Baker, Don (2006). "The religious revolution in modern Korean history: From ethics to theology and from ritual hegemony to religious freedom". Review of Korean Studies. 9 (3): 249–275.

- Baker, Don (19 June 2015). Creating the sacred and the secular in colonial Korea (PDF). workshop on secularism in Japan. University of Oslo, Norway. pp. 1–37.

- Beirne, Paul Su-un and His World of Symbols: the Founder of Korea's First Indigenous Religion. Routledge. 2019. ISBN 9780754662846.

- Chung, Kiyul The Donghak Concept of God/Heaven: Religion and Social Transformation. Peter Lang. 2007. ISBN 9780820488219.

- Kallander, George L. Salvation through Dissent: Tonghak Heterodoxy and Early Modern Korea. University of Hawai'i Press. 2013. ISBN 9780824837167.

- Kim, Sun Joo (2007). "Taxes, the local elite, and the rural populace in the Chinju Uprising of 1862". International Journal of Korean History. 66 (4): 993–1027. JSTOR 20203239 – via JSTOR.

- Kim, Young Choon; Yoon, Suk San; with Central Headquarters of Chongdogyo (2007). Chondogyo Scripture: Donggyeong Daejeon (Great Scripture of Eastern Learning). University Press of America. ISBN 9780761838029.

- Moon, Sr. Myongsook (2017). "Donghak and the God of Choe, Je-u: through the Donggyeong Daejeon and the Yongdam Yusa". Catholic Theology and Thought. 79: 218–260. doi:10.21731/ctat.2017.79.218. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- Park, So Jeong (2016). "Philosophizing Jigi 至氣 of Donghak 東學". Journal of Confucian Philosophy and Culture. 26: 81–100. Retrieved 25 June 2021.

- Shin, Susan S. (1978–79). "The Tonghak movement: from enlightenment to revolution". Korea Journal. 5: 1-80 (not seen, cited by Beirne 2019).

- Shin, Susan S. (1979). "Tonghak Thought: The Roots of Revolution" (PDF). Korea Journal. 19 (9): 11–19.

- Spence, Jonathan D. God's Chinese Son: The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom of Hong Xiuquan. W.W. Norton. 1996. ISBN 9780393315561.

- Weems, Benjamin B. Reform, Rebellion, and the Heavenly Way. University of Arizona Press. 1966. ISBN 9781135748388.

- Young, Carl (2013). "Into the Sunset: Ch'ŏndogyo in North Korea, 1945—1950". Journal of Korean Religions. 4 (2): 51–66. doi:10.1353/jkr.2013.0010. JSTOR 23943354. S2CID 143642559.

- Young, Carl E. Eastern Learning and the Heavenly Way: The Tonghak and Ch'ŏndogyo Movements and the Twilight of Korean Independence. University of Hawai'i Press. 2014. ISBN 9780824838881.

References

- Kim and Yoon 2007, p. 55-57.

- Park 2016, p. 82.

- A Handbook of Korea (9th ed.). Seoul: Korean Overseas Culture and Information Service. December 1993. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-1-56591-022-5.

- Kallander 2013, p. XX.

- Shin,Susan 1979, p. 18.

- Kallander 2013, p. 81.

- Kim and Yoon 2007, p. 56.

- Beirne 2019, p. 5.

- Kallander 2013, p. 39.

- Beirne 2019, p. 19.

- Kallander 2013, p. 40.

- Kallander 2013, p. 41.

- Shin,Susan 1979, p. 6.

- Kallander 2013, p. 154.

- Beirne 2019, p. 28.

- Ahn 2001, p. 160.

- Beirne 2019, p. 25.

- Beirne 2019, p. 41.

- Beirne 2019, p. 97.

- Beirne 2019, p. 123.

- Beirne 2019, p. 136-137.

- Beirne 2019, p. 160-161.

- Kallander 2013, p. ix.

- Bae 2020, p. 14.

- Shin,Susan 1979, p. 11.

- Chung 2007, p. 49-52.

- Ahn 2001, p. 62-64.

- Baker 2006, p. 257&265-266.

- Shin,Susan 1979, p. 14.

- Kallander 2013, p. 59, Map 3.1.

- Kim and Yoon 2007, p. 56-57.

- Young 2013, p. 157-169.

- Kim 2007, p. 993–1027.

- Spence 1996, p. 325.

- Beirne 2019, p. 6.

- Kallander 2013, p. 117-121.

- Young 2014, p. 53,62.

- Young 2014, p. 79.

- Baker 2015, p. 19.

- Weems 1966, p. 72-73.

- Young 2013, p. 52.

- Moon 2017, p. 258.