Dancing mania

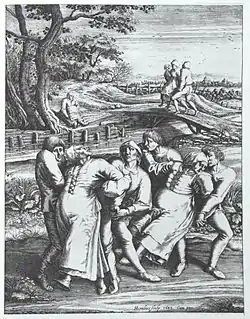

Dancing mania (also known as dancing plague, choreomania, St. John's Dance, tarantism and St. Vitus' Dance) was a social phenomenon that occurred primarily in mainland Europe between the 14th and 17th centuries. It involved groups of people dancing erratically, sometimes thousands at a time. The mania affected adults and children who danced until they collapsed from exhaustion and injuries. One of the first major outbreaks was in Aachen, in the Holy Roman Empire (in modern-day Germany), in 1374, and it quickly spread throughout Europe; one particularly notable outbreak occurred in Strasbourg in 1518 in Alsace, also in the Holy Roman Empire (now in modern-day France).

Affecting thousands of people across several centuries, dancing mania was not an isolated event, and was well documented in contemporary reports. It was nevertheless poorly understood, and remedies were based on guesswork. Often musicians accompanied dancers, due to a belief that music would treat the mania, but this tactic sometimes backfired by encouraging more to join in. There is no consensus among modern-day scholars as to the cause of dancing mania.[1]

The several theories proposed range from religious cults being behind the processions to people dancing to relieve themselves of stress and put the poverty of the period out of their minds. It is speculated to have been a mass psychogenic illness, in which physical symptoms with no known physical cause are observed to affect a group of people, as a form of social influence.[1]

Definition

"Dancing mania" is derived from the term "choreomania", from the Greek choros (dance) and mania (madness),[2]: 133–134 [3] and is also known as "dancing plague".[4]: 125 The term was coined by Paracelsus,[4]: 126 and the condition was initially considered a curse sent by a saint,[5] usually St. John the Baptist[6]: 32 or St. Vitus, and was therefore known as "St. Vitus' Dance" or "St. John's Dance". Victims of dancing mania often ended their processions at places dedicated to that saint,[2]: 136 who was prayed to in an effort to end the dancing;[4]: 126 incidents often broke out around the time of the feast of St. Vitus.[7]: 201

St. Vitus' Dance was diagnosed, in the 17th century, as Sydenham chorea.[8] Dancing mania has also been known as epidemic chorea[4]: 125 and epidemic dancing.[5] A disease of the nervous system, chorea is characterized by symptoms resembling those of dancing mania,[2]: 134 which has also rather unconvincingly been considered a form of epilepsy.[6]: 32

Other scientists have described dancing mania as a "collective mental disorder", "collective hysterical disorder" and "mass madness".[2]: 136

Outbreaks

The earliest-known outbreak of dancing mania occurred in the 7th century,[9] and it reappeared many times across Europe until about the 17th century, when it stopped abruptly.[2]: 132 One of the earliest-known incidents occurred sometime in the 1020s in Bernburg, where 18 peasants began singing and dancing around a church, disturbing a Christmas Eve service.[7]: 202

Further outbreaks occurred during the 13th century, including one in 1237 in which a large group of children travelled from Erfurt to Arnstadt (about 20 km (12 mi)), jumping and dancing all the way,[7]: 201 in marked similarity to the legend of the Pied Piper of Hamelin, a legend that originated at around the same time.[9] Another incident, in 1278, involved about 200 people dancing on a bridge over the River Meuse resulting in its collapse. Many of the survivors were restored to full health at a nearby chapel dedicated to St. Vitus.[2]: 134 The first major outbreak of the mania occurred between 1373 and 1374, with incidents reported in England, Germany and the Netherlands.[6]: 33

On 24 June 1374, one of the biggest outbreaks began in Aachen,[4]: 126 before spreading to other places such as Cologne, Flanders, Franconia, Hainaut, Metz, Strasbourg, Tongeren, Utrecht,[6]: 33 and regions and countries such as Italy and Luxembourg. Further episodes occurred in 1375 and 1376, with incidents in France, Germany, and the Netherlands,[2]: 138 and in 1381, there was an outbreak in Augsburg.[6]: 33 Further incidents occurred in 1418 in Strasbourg, where people fasted for days and the outbreak was possibly caused by exhaustion.[2]: 137 In another outbreak, in 1428 in Schaffhausen, a monk danced to death and, in the same year, a group of women in Zürich were reportedly in a dancing frenzy.

Another of the most extensive outbreaks occurred in July 1518, in Strasbourg (see Dancing plague of 1518), where a woman began dancing in the street, and between 50 and 400 people joined her.[6]: 33 Further incidents occurred during the 16th century when the mania was at its peak: in 1536 in Basel, involving a group of children; and in 1551 in Anhalt, involving just one man.[6]: 37 In the 17th century, incidents of recurrent dancing were recorded by professor of medicine Gregor Horst, who noted:

Several women who annually visit the chapel of St. Vitus in Drefelhausen... dance madly all day and all night until they collapse in ecstasy. In this way they come to themselves again and feel little or nothing until the next May, when they are again... forced around St. Vitus' Day to betake themselves to that place... [o]ne of these women is said to have danced every year for the past twenty years, another for a full thirty-two.[6]: 39

Dancing mania appears to have completely died out by the mid-17th century.[6]: 46 According to John Waller, although numerous incidents were recorded, the best documented cases are the outbreaks of 1374 and 1518, for which there is abundant contemporary evidence.[5]

Characteristics

The outbreaks of dancing mania varied, and several characteristics of it have been recorded. Generally occurring in times of hardship,[2]: 136 up to tens of thousands of people would appear to dance for hours,[2]: 133 [10] days, weeks, and even months.[2]: 132 [5]

Women have often been portrayed in modern literature as the usual participants in dancing mania, although contemporary sources suggest otherwise.[2]: 139 Whether the dancing was spontaneous, or an organized event, is also debated.[2]: 138 What is certain, however, is that dancers seemed to be in a state of unconsciousness[7]: 201 and unable to control themselves.[2]: 136

In his research into social phenomena, author Robert Bartholomew notes that contemporary sources record that participants often did not reside where the dancing took place. Such people would travel from place to place, and others would join them along the way. With them they brought customs and behaviour that were strange to the local people.[2]: 137 Bartholomew describes how dancers wore "strange, colorful attire" and "held wooden sticks".[2]: 132

Robert Marks, in his study of hypnotism, notes that some decorated their hair with garlands.[7]: 201 However, not all outbreaks involved foreigners, and not all were particularly calm. Bartholomew notes that some "paraded around naked"[2]: 132 and made "obscene gestures".[2]: 133 Some even had sexual intercourse.[2]: 136 Others acted like animals,[2]: 133 and jumped,[6]: 32 hopped and leaped about.[6]: 33

They hardly stopped,[10] and some danced until they broke their ribs and subsequently died.[6]: 32 Throughout, dancers screamed, laughed, or cried,[2]: 132 and some sang.[11]: 60 Bartholomew also notes that observers of dancing mania were sometimes treated violently if they refused to join in.[2]: 139 Participants demonstrated odd reactions to the color red; in A History of Madness in Sixteenth-Century Germany, Midelfort notes they "could not perceive the color red at all",[6]: 32 and Bartholomew reports "it was said that dancers could not stand... the color red, often becoming violent on seeing [it]".

Bartholomew also notes that dancers "could not stand pointed shoes", and that dancers enjoyed their feet being hit.[2]: 133 Throughout, those affected by dancing mania suffered from a variety of ailments, including chest pains, convulsions, hallucinations, hyperventilation,[2]: 136 epileptic fits,[4]: 126 and visions.[12]: 71 In the end, most simply dropped down, overwhelmed with exhaustion.[4]: 126 Midelfort, however, describes how some ended up in a state of ecstasy.[6]: 39 Typically, the mania was contagious but it often struck small groups, such as families and individuals.[6]: 37–38

Tarantism

In Italy, a similar phenomenon was tarantism, in which the victims were said to have been poisoned by a tarantula or scorpion. Its earliest-known outbreak was in the 13th century, and the only antidote known was to dance to particular music to separate the venom from the blood.[2]: 133 It occurred only in the summer months. As with dancing mania, people would suddenly begin to dance, sometimes affected by a perceived bite or sting and were joined by others, who believed the venom from their own old bites was reactivated by the heat or the music.[2]: 134 Dancers would perform a tarantella, accompanied by music which would eventually "cure" the victim, at least temporarily.[2]: 135

Some participated in further activities, such as tying themselves up with vines and whipping each other, pretending to sword fight, drinking large amounts of wine, and jumping into the sea. Sufferers typically had symptoms resembling those of dancing mania, such as headaches, trembling, twitching and visions.[2]: 134

As with dancing mania, participants apparently did not like the color black,[2]: 133 and women were reported to be most affected.[2]: 136 Unlike dancing mania, tarantism was confined to Italy and southern Europe. It was common until the 17th century, but ended suddenly, with only very small outbreaks in Italy until as late as 1959.[2]: 134

A study of the phenomenon in 1959 by religious history professor Ernesto de Martino revealed that most cases of tarantism were probably unrelated to spider bites. Many participants admitted that they had not been bitten, but believed they were infected by someone who had been, or that they had simply touched a spider. The result was mass panic, with a "cure" that allowed people to behave in ways that were, normally, prohibited at the time.[2]: 135 Despite their differences, tarantism and dancing mania are often considered synonymous.[2]: 134

Reactions

As the real cause of dancing mania was unknown, many of the treatments for it were simply hopeful guesses, although some did seem effective. The 1374 outbreak occurred only decades after the Black Death, and was treated in a similar fashion: dancers were isolated, and some were exorcised.[12]: 70 People believed that the dancing was a curse brought about by St. Vitus;[10] they responded by praying[4]: 126 and making pilgrimages to places dedicated to St. Vitus.[6]: 34

Prayers were also made to St. John the Baptist, who some believed also caused the dancing.[6]: 32 Others claimed to be possessed by demons,[2]: 136 or Satan,[10] therefore exorcisms were often performed on dancers.[11]: 60 Bartholomew notes that music was often played while participants danced, as that was believed to be an effective remedy,[2]: 136 and during some outbreaks musicians were even employed to play.[2]: 139 Midelfort describes how the music encouraged others to join in, however, and thus effectively made things worse, as did the dancing places that were sometimes set up.[6]: 35

Theories

Numerous hypotheses have been proposed for the causes of dancing mania, and it remains unclear whether it was a real illness or a social phenomenon. One of the most prominent theories is that victims suffered from ergot poisoning, which was known as St. Anthony's fire in the Middle Ages. During floods and damp periods, ergots were able to grow and affect rye and other crops. Ergotism can cause hallucinations and convulsions, but cannot account for the other strange behaviour most commonly identified with dancing mania.[2]: 140 [4]: 126 [6]: 43 [10]

Other theories suggest that the symptoms were similar to encephalitis, epilepsy, and typhus, but as with ergotism, those conditions cannot account for all symptoms.[4]: 126

Numerous sources discuss how dancing mania, and tarantism, may have simply been the result of stress and tension caused by natural disasters around the time,[6]: 43 such as plagues and floods.[12]: 72 Hetherington and Munro describe dancing mania as a result of "shared stress";[12]: 73 people may have danced to relieve themselves of the stress and poverty of the day,[12]: 72 and in so doing, attempted to become ecstatic and see visions.[13]

Another popular theory is that the outbreaks were all staged,[12]: 71 and the appearance of strange behaviour was due to its unfamiliarity.[2]: 137 Religious cults may have been acting out well-organised dances, in accordance with ancient Greek and Roman rituals.[2]: 136 [2]: 137 Despite being banned at the time, these rituals could be performed under the guise of uncontrollable dancing mania.[2]: 140 Justus Hecker, a 19th-century medical writer, described it as a kind of festival, where a practice known as "the kindling of the Nodfyr" was carried out. This involved jumping through fire and smoke, in an attempt to ward off disease. Bartholomew notes how participants in this ritual would often continue to jump and leap long after the flames had gone.[2]: 139

It is certain that many participants of dancing mania were psychologically disturbed,[2]: 136 but it is also likely that some took part out of fear,[10] or simply wished to copy everyone else.[6]: 43 Sources agree that dancing mania was one of the earliest-recorded forms of mass hysteria,[2]: 135 [12]: 73 and describe it as a "psychic epidemic", with numerous explanations that might account for the behaviour of the dancers.[6]: 43 It has been suggested that the outbreaks may have been due to cultural contagion triggered, in times of particular hardship, by deeply rooted popular beliefs in the region regarding angry spirits capable of inflicting a "dancing curse" to punish their victims.[5]

See also

- Dance marathon

- Ee ja nai ka, a cultural practice in 19th-century Japan with some similarities

- Flash mobs sometimes come together to dance

- Maenads, a somewhat similar religious practice in ancient Greece

- Social contagion

References

- Sirois, F. (1982). "Perspectives on epidemic hysteria". In Colligan, M. J.; Pennebaker, J. W.; Murphy, L. R. (eds.). Mass psychogenic illness: A social psychological analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. pp. 217–236. ISBN 0-89859-160-0.

- Bartholomew, Robert E. (2001). Little green men, meowing nuns, and head-hunting panics. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0997-6.

- χορός, μανία. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- Dirk Blom, Jan (2009). A Dictionary of Hallucinations. Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-1222-0.

- Waller J (February 2009). "A forgotten plague: making sense of dancing mania". Lancet. 373 (9664): 624–625. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60386-X. PMID 19238695. S2CID 35094677. Archived from the original on 8 November 2014. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- Midelfort, H. C. Erik (2000). A History of Madness in Sixteenth-Century Germany. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4169-9.

- Marks, Robert W. (2005). The Story of Hypnotism. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4191-5424-9.

- "NINDS Sydenham Chorea Information Page". NINDS. US: NIH. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- Schullian, DM (1977). "The Dancing Pilgrims at Muelebeek". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. Oxford University Press. 32 (3): 315–319. doi:10.1093/jhmas/xxxii.3.315. PMID 326865.

- Waller, John (July 2009). "Dancing plagues and mass hysteria". The Psychologist. UK: British Psychological Society. 22 (7): 644–647. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015.

- Vuillier, Gaston (2004). History of Dancing from the Earliest Ages to Our Own Times. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7661-8166-3.

- Hetherington, Kevin; Munro, Rolland (1997). Ideas of difference. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20768-9.

- Feldman, Marc D.; Feldman, Jacqueline M.; Smith, Roxenne (1998). Stranger than fiction: when our minds betray us. American Psychiatric Press. p. 191. ISBN 978-0-88048-930-0.

Further reading

- Dancing Mania, by Leah Esterianna & Richard the Poor of Ely

- Bartholomew RE (May 1994). "Tarantism, dancing mania and demonopathy: the anthro-political aspects of 'mass psychogenic illness'". Psychol Med. 24 (2): 281–306. doi:10.1017/S0033291700027288. PMID 8084927. S2CID 13090774.

- Donaldson LJ, Cavanagh J, Rankin J (July 1997). "The dancing plague: a public health conundrum". Public Health. 111 (4): 201–204. doi:10.1016/S0033-3506(97)00034-6. PMID 9242030.

- Giménez-Roldán S, Aubert G (June 2007). "Hysterical chorea: Report of an outbreak and movie documentation by Arthur Van Gehuchten (1861–1914)". Mov. Disord. 22 (8): 1071–1076. doi:10.1002/mds.21293. PMID 17230482. S2CID 23556702.

- Hecker, Justus (1859). The dancing mania of the Middle Ages.

- Hecker, J. F. C. (Justus Friedrich Carl) (1888). Morley, Henry (ed.). The black death and the dancing mania. Translated by Babington, B. G. (Benjamin Guy). Woodruff Health Sciences Center Library Emory University. Cassell & Company. pp. 105–192. OCLC 00338041.

- Krack P (December 1999). "Relicts of dancing mania: the dancing procession of Echternach". Neurology. 53 (9): 2169–2172. doi:10.1212/wnl.53.9.2169. PMID 10599799. S2CID 36892826.

- Okun MS, Thommi N (July 2004). "Americo Negrette (1924 to 2003): diagnosing Huntington disease in Venezuela". Neurology. 63 (2): 340–343. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000129827.16522.78. PMID 15277631. S2CID 24618596.

- Waller, John (2008). A Time to Dance, A Time to Die. Icon Books. ISBN 978-1-84831-021-6.

- Waller, John (12 September 2008). "Dancing death". BBC.

- Waller, John (18 September 2008). "Falling down". The Guardian.

- Davidson, Andrew (1867). "Choreomania: An Historical Sketch" (PDF). Oliver and Boyd. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

External links

![]() Media related to Dancing mania at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dancing mania at Wikimedia Commons

The Dancing Mania public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Dancing Mania public domain audiobook at LibriVox