Choroidal nevus

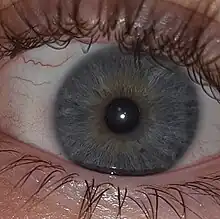

Choroidal nevus (plural: nevi) is a type of eye neoplasm that is classified under choroidal tumors as a type of benign (non-cancerous) melanocytic tumor.[1] A choroidal nevus can be described as an unambiguous pigmented blue or green-gray choroidal lesion, found at the front of the eye, around the iris,[2] or the rear end of the eye.[3][4]

| Choroidal Nevus | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Eye nevus, Eye freckle |

| |

| Picture of Choroidal nevus | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

| Causes | Unknown |

Nevi are usually darkly pigmented tumors because they comprise melanocytes. Dr. Gass, one of the leading specialists on eye diseases, speculates that a choroidal nevus grows from small cells resting as hyperplastic lesions, and exhibits growth primarily.[5] In most cases, choroidal nevus is an asymptomatic disease, however, in serious conditions, adverse symptoms can be observed.

Choroidal nevus is usually diagnosed through an ophthalmic eye examination, or more specialized technologies such as photographic imaging, ophthalmoscopy, ultrasonography and ocular coherence tomography (OCT). Choroidal nevi can transform into a choroidal or ocular melanoma, becoming cancerous. Therefore, it is crucial to differentiate between a non-cancerous choroidal nevus and lethal melanoma.

Prevalence

The prevalence of choroidal nevus among the United States adult population above 40 years old is 4.7%.[4] In terms of ethnicity, a cohort study done in the United States reported that the prevalence of choroidal nevus was found more in whites (4.1%) than in Chinese (0.4%), blacks (0.7%) and Hispanics (1.2%). However, the difference between Chinese, blacks and Hispanics was not statistically significant. The prevalence of choroidal nevus did not vary between sex, but it did vary with age. The incidence of nevi was discovered to be highest in people between the ages of 55 to 74 and lowest in people aged between 75 and 84.[6] Hence, it is likely that there is a higher prevalence of the disease in people who are comparatively younger.

Another study on the prevalence of choroidal nevus among the female population investigated the role of obesity and reproductive factors in the development of the disease. Among premenopausal women, the risk of developing nevus is shown to be four times higher in those who had their first child before 25, compared to those who had their first child after 35. Moreover, among postmenopausal females, the prevalence in obese females was twice that of non-obese females.[7]

Signs and symptoms

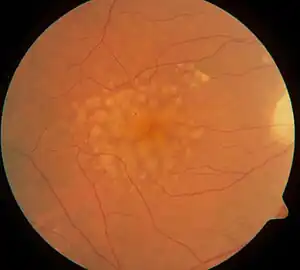

Location of the nevi plays a role in determining whether the disease is associated with any symptoms. In unusual circumstances, when the nevus is located below the center of the retina, blurred vision[8] is the result. When a choroidal nevus becomes severe, it can cause leakage of fluid and abnormal development of vascular tissue[9] (neovascularization[10]). This leads to retinal detachment in that part of the eye, which is observed as some loss of vision or flashing lights.[9] Once retinal detachment occurs, the case becomes a surgical emergency. Additionally, if the nevus is present for an extended period of time (years), and hinders the removal of retinal waste products, this can result in the development of yellowish white specks and spots on the surface of the nevi,[9] called drusen.

Cause

Currently, the cause of choroidal nevus is unknown.

Forms of choroidal nevi

There are different ways to describe a choroidal nevus with its specific characteristics, such as halo choroidal nevus, giant choroidal nevus, and choroidal nevus with drusen. It is important to note that these characteristics and forms of nevi can and may overlap and be present at the same time.

Halo choroidal nevus

Halo choroidal nevus is described as a yellow halo around the darkly pigmented brown centre, or in other terms, a pigmented centre with a hypo-pigmented periphery. Halo nevi contribute to 5% of all choroidal nevi.[11] The pathogenesis of the halo nevus is not known,[1] but the presence of a halo around the choroidal nevus was statistically proven to have a relatively lower risk of transforming into melanoma and thus is a predictive factor for stability.[12][11] A few indicators of a halo nevus include an absence of subretinal fluid and orange pigment, thickness level less than 2 mm, as well as the tumor margin being remote from the optic disk.[1]

Giant choroidal nevus

Giant choroidal nevus is described as one that has a basal diameter larger than 10mm. This variant contributes to 8% of all choroidal nevi.[13] Due to its large basal diameter and thickness, it can be easily mistaken and diagnosed as choroidal melanoma.[13] However, it does have the potential to grow into a melanoma. One study reported that over a period of 10 years, 18% of giant nevi grew into melanomas.[13] Some of the most common features observed among these transformed giant nevi are nearness to the foveola and ultrasonographic acoustic hollowness,[13] suggesting that these may be the reasons for the transformation into melanomas. Thus, patients with giant nevus require close monitoring.

Choroidal nevus with drusen

Choroidal nevus with drusen can be considered as a sign of chronicity since drusen take years to develop and appear.[14] Drusen are composed of lipids and can actually be an indicator that a tumour is a benign nevus as opposed to a cancerous melanoma.[15] In nevi imaged by OCT, about 41% are found to have drusen.[16]

Transformation of a nevus into melanoma

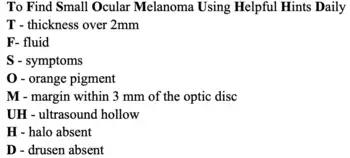

Naturally, nevi occur more frequently than melanoma.[17] Research shows that only about 1 in 9000 (in the United States population)[8] transform into melanomas. Patients are at particularly high risk if the following is observed:

- A tumor thickness greater than 2mm[18] or a tumor two times or more larger than the optic nerve head.[9]

- Symptoms such as decreased vision (lower acuity),[19] flashing lights and orange pigment[18] on or surrounding the tumor.[9]

- Distance between the margin of the tumor and the optic disk is less than 3mm.

- Subretinal fluid[18] (i.e. the leakage of fluid[9]).

- Ultrasonographic hollowness. In one study, 25% of nevi with hollowness on ultrasonography transformed into melanoma.[18]

- Lack of halo. The presence of a halo is associated with stability of the nevi. This is illustrated by a study which reported that 7% of nevi in the absence of halo, grew into melanoma.[18]

If three or more of the above melanoma risk factors are observed, the risk of the choroidal nevus growing into a melanoma is greater than 50%.[12]

Pathophysiology and cytogenetics

The pathophysiology of choroidal melanoma (a type of uveal melanoma), is not well understood.[20] However, several molecular mechanisms and cytogenetics may be involved in the process of it becoming malignant. Chromosomal alterations, monosomy 3 and chromosome 8 gains have been identified to be associated with metastasis in uveal melanomas.[1][21] Moreover BAP1, GNAQ, GNA11, SF3B1 and EIF1AX gene alterations were shown to be in correlation with uveal melanomas, each with a frequency of 18–45%.[21]

Other risk factors

Although transformation into a melanoma is considered to be sporadic,[20] several general risk factors are identified to be potentially relevant to the malignant transformation. These include light iris color, generally lower levels of melanin (light and untanned skin tones), exposure to arc welding due to intermittent ultraviolet exposure,[22][23] as well as diseases such as ocular melanocytosis and dysplastic nevus syndrome.[23]

Differentiating between choroidal nevi and melanomas

Choroidal nevus has a few features that differentiate it from a choroidal melanoma, its malignant tumor form. Speed of growth: Nevi with slow growth in terms of size and in the absence of melanoma risk factors, do not show any signs of malignancy. The process of enlargement of the nevus can take up to an average of 15 years.[24] In a long-term follow up study on the growth of choroidal nevi, out of 284 nevi, 31% of the patients only showed slight enlargement of choroidal nevi without any clinical evidence or signs of transformation into melanoma.[24] In contrast, for small melanomas, the speed of growth is much faster,[13][24] making it easily detectable in a short period of time. In fact, melanomas grow exponentially in thickness during their active growth phase.[24]

Ability to metastasis: Choroidal melanomas are able to undergo distant metastasis, whereas choroidal nevus is unable to do so.[24]

Risks factors for prediction of growth: There is a lack of overlap between the risk factors for the prediction of growth or enlargement of nevus and melanoma. While choroidal melanomas have multiple risk factors including even UV exposure and welding, the only risk factor for choroidal nevus is age.[24] Slow growth and enlargement of choroidal nevi are found to be more common in younger patients, before becoming stable in mid or late adulthood.[24]

Diagnosis

Unless the choroidal nevus has progressed to a symptomatic form, it can only be discovered during a normal eye examination.[8] The nevus is identified by its distinctive appearance. With a thickness of approximately 2mm and a color between brown to slate gray, the edge of the nevus blends into the retina.[8] It is entirely possible to have more than one nevus in an eye, or have nevi in both eyes.[8]

Diagnostic testing is carried out by ultrasound, fluorescein angiography and OCT.[8] Both OCT and ultrasound fall under ophthalmic diagnostic imaging,[17] allowing practitioners to take direct photographs of eye surfaces. The retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) can be captured as well, using autofluorescence, because the light waves can detect lipofuscin.[17]

A B-scan ultrasound provides the practitioner with an approximate size of the tumor, in addition to vertical and horizontal measurements,[14] while an A-scan determines the amount of internal reflectivity.[14] On the other hand, fluorescein angiography will aid in recognizing whether the tumor has developed its own circulation network.[14]

Optomap is a common diagnostic tool in recognizing a choroidal nevus from a melanoma.[14] It takes an image of the nevus or melanoma using two different lasers - which are red and green.[14] When using the green laser to view the retina, a nevus would be invisible while a melanoma would be visible.[14] Hence, optomap can distinguish a nevus from a melanoma.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) may have the potential for clinical diagnosis of choroidal nevus or melanoma. This can be achieved through machine learning, whereby a large dataset of imaging photographs of all sizes, shapes and location of nevi are used in training.[17] This would improve detection accuracy as well as the design of treatment for nevi and melanoma.[17]

Treatment

Since typical choroidal nevi do not have adverse effects, treatment is not required. Additionally, there are no safe methods to remove nevi from the eye as of now.[10] Nonetheless, annual evaluations and checkups by ophthalmologists are necessary. The American Academy of Ophthalmology recommends adults aged 40 and above to have full eye examinations, as vision loss and eye diseases are most likely to start around this age.[25]

Most choroidal nevi can be managed and monitored by OCT. However, the abnormal development of vascular tissue as a result of the development of nevi can be treated using anti-VEGF agents, injected through the veins.[8] These drugs inactivate the growth factor (VEGF) to reduce neovascularization and swelling.[8] If the choroidal nevus does transform into a melanoma, then it would be treated with cancer therapy.

References

- Chien, Jason L.; Sioufi, Kareem; Surakiatchanukul, Thamolwan; Shields, Jerry A.; Shields, Carol L. (May 2017). "Choroidal nevus: a review of prevalence, features, genetics, risks, and outcomes". Current Opinion in Ophthalmology. 28 (3): 228–237. doi:10.1097/ICU.0000000000000361. PMID 28141766. S2CID 19367181.

- Boyd, Kierstan (2022-01-11). "Nevus (Eye Freckle)". American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- Sumich, P.; Mitchell, P.; Wang, J.J. (1998). "Choroidal nevi in a white population: the Blue Mountains Eye Study". Archives of Ophthalmology. 116 (5): 645–650. doi:10.1001/archopht.116.5.645. PMID 9596501.

- Qiu, Mary; Shields, Carol L. (2015). "Choroidal Nevus in the United States Adult Population: Racial Disparities and Associated Factors in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey". Ophthalmology. 122 (10): 2071–2083. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2015.06.008. PMID 26255109.

- Gass, J.D. (1977). "Problems in the differential diagnosis of choroidal nevi and malignant melanomas. The XXXIII Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture". American Journal of Ophthalmology. 83 (3): 299–323. doi:10.1089/ten.2005.11.1254. PMID 848534.

- Greenstein, M. B.; Myers, C. E.; Meuer, S.M.; Klein, B. E.; Cotch, M. F.; Wong, T. Y.; Klein, R. (2011). "Prevalence and characteristics of choroidal nevi: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis". Ophthalmology. 118 (12): 2468–73. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2011.05.007. PMC 3213310. PMID 21820181.

- Qiu, Mary; Shields, Carol L. (2015). "Relationship Between Female Reproductive Factors and Choroidal Nevus in US Women: Analysis of Data From the 2005-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey". JAMA Ophthalmology. 133 (11): 1287–1294. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2015.3178. PMID 26402791.

- "Choroidal Nevus - Patients - The American Society of Retina Specialists". www.asrs.org.

- Optometrist, Dr J. R. Lacey, Therapeutic. "Choroidal Nevus: A Common Eye Condition that can Become Lethal". www.mastereyeassociates.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Choroidal Nevus » New York Eye Cancer Center". New York Eye Cancer Center. 25 April 2016.

- Shields, C. L.; Maktabi, A. M.; Jahnle, E.; Mashayekhi, A.; Lally, S. E.; Shields, J. A (2010). "Halo nevus of the choroid in 150 patients: the 2010 Henry van Dyke Lecture". Archives of Ophthalmology. 128 (7): 859–864. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2010.132. PMID 20625046.

- Shields, C. L.; Furuta, M. M.; Berman, E.L.; Zahler, J.D.; Hoberman, D.M.; Dinh, D.H.; Mashayekhi, A.; Shields, J.A. (2009). "Choroidal nevus transformation into melanoma: analysis of 2514 consecutive cases". Archives of Ophthalmology. 127 (8): 981–987. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.151. PMID 19667334.

- Li, H. K.; Shields, C. L.; Mashayekhi, A.; Randolph, J.D.; Bailey, T.; Burnbaum, J. Y.; Shields, J.A. (2010). "Giant choroidal nevus clinical features and natural course in 322 cases". Ophthalmology. 117 (2): 324–333. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.07.006. PMID 19969359.

- "Differential diagnosis of ocular melanoma vs. choroidal nevus is crucial". www.healio.com.

- Shields, Carol L.; Kels, Jane Grant; Shields, Jerry A. (2015). "Melanoma of the eye: revealing hidden secrets, one at a time". Clinics in Dermatology. 33 (2): 183–196. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.10.010. ISSN 1879-1131. PMID 25704938.

- Jonna, Gowtham; Daniels, Anthony B. (2019). "Enhanced Depth Imaging Optical Coherence Tomography of Ultrasonographically Flat Choroidal Nevi Demonstrates 5 Distinct Patterns". Ophthalmology. Retina. 3 (3): 270–277. doi:10.1016/j.oret.2018.10.004. ISSN 2468-7219. PMC 7906427. PMID 31014705.

- Shields, Carol L.; Lally, Sara E.; Dalvin, Lauren A.; et al. (17 February 2021). "White Paper on Ophthalmic Imaging for Choroidal Nevus Identification and Transformation into Melanoma". Translational Vision Science & Technology. 10 (2): 24. doi:10.1167/tvst.10.2.24. ISSN 2164-2591. PMC 7900849. PMID 34003909.

- Shields, Carol L.; Furuta, Minoru; Berman, Edwina L.; Zahler, Jonathan D.; Hoberman, Daniel M.; Dinh, Diep H.; Mashayekhi, Arman; Shields, Jerry A. (1 August 2009). "Choroidal Nevus Transformation Into Melanoma: Analysis of 2514 Consecutive Cases". Archives of Ophthalmology. 127 (8): 981–987. doi:10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.151. ISSN 0003-9950. PMID 19667334.

- Shields, C.L.; Dalvin, L.A.; Ancona-Lezama, D.; et al. (2019). "CHOROIDAL NEVUS IMAGING FEATURES IN 3,806 CASES AND RISK FACTORS FOR TRANSFORMATION INTO MELANOMA IN 2,355 CASES: The 2020". Retina. 39 (10): 1840–1851. doi:10.1097/IAE.0000000000002440. PMID 30608349. S2CID 58539759.

- Monsivais-Rodríguez, Fabiola V.; Sweeney, Adam; Stacey, Andrew W.; Gupta, Divakar; Fry, Constance (19 January 2022). "Clinical Evaluation of Choroidal Melanoma". EyeWiki. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- Krantz, Benjamin A.; Dave, Nikita; Komatsubara, Kimberly M.; Marr, Brian P.; Carvajal, Richard D. (2017). "Uveal melanoma: epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of primary disease". Clinical Ophthalmology. 11: 279–289. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S89591. ISSN 1177-5467. PMC 5298817. PMID 28203054.

- Shah, C.P.; Weis, E.; Lajous, M.; Shields, J.A.; Shields, C.L. (2005). "Intermittent and chronic ultraviolet light exposure and uveal melanoma: a meta-analysis". Ophthalmology. 112 (9): 1599–1607. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2005.04.020. PMID 16051363.

- Krantz, B.A.; Dave, N.; Komatsubara, K.M.; Marr, B. P.; Carvajal, R. D. (2017). "Uveal melanoma: epidemiology, etiology, and treatment of primary disease". Clinical Ophthalmology. 11: 279–289. doi:10.2147/OPTH.S89591. PMC 5298817. PMID 28203054.

- Mashayekhi, A.; Siu, S.; Shields, C.L.; Shields, J.A. (2011). "Slow enlargement of choroidal nevi: a long-term follow-up study". Ophthalmology. 118 (2): 382–388. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.06.006. PMID 20801518.

- Seltman, Whitney (7 November 2021). "How Often Should I Get My Eyes Checked?". WebMD. Retrieved 2 April 2022.