Christopher Sykes (politician)

Christopher Sykes (1831 – 15 December 1898) was an English Conservative politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1865 to 1892.[2] He enjoyed the "intimate friendship" of Edward VII when Prince of Wales and Alexandra of Denmark when Princess of Wales.[2]

Sykes was the second son of Sir Tatton Sykes, 4th Baronet, and his wife Mary Ann Foulis, daughter of Sir William Foulis, 7th Baronet.[2][3] His father was a popular horse breeder who bred bloodstock; however, he was an authoritarian father who bullied his children.[4] Sykes was educated at Rugby School and Trinity College, Cambridge.[2][5] He began mixing with London's great and good and became a connoisseur of books, china and furniture. He was a Deputy Lieutenant and J.P. for the East Riding of Yorkshire.[2][3]

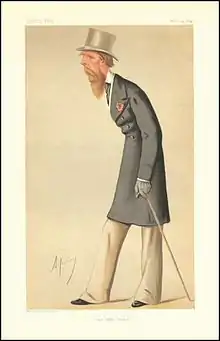

At the 1865 general election Sykes was elected Conservative Member of Parliament (MP) for Beverley.[2] At the 1868 general election he was elected MP for the East Riding of Yorkshire, which he held until 1885, when it was divided under the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885.[2] He was then elected for Buckrose, one of the constituencies into which his previous constituency had been divided, which he held until 1892, when he retired. [2] Between 1868 and 1892, he made only six speeches, and did little except introduce the bill which became the Sea Birds Preservation Act 1869.[2] This led to him being caricatured in Vanity Fair as "The Gull's friend".[6] He was "widely recognised" as "Mr Brancepath" in Lothair, the novel by Benjamin Disraeli.[2] He was honoured with the Order of St Lazarus of Belgium in 1879.[5]

Sykes became a close friend of Edward VII as Prince of Wales, who - because of his great height - called him the "great Xtopher", (pronounced "Christopher").[7] Sykes entertained the prince and princess in great splendour at Brantingham Thorpe, his country house in Yorkshire, the Doncaster Races, and his London home in Berkeley Square.[8] One night, at the Marlborough Club, the Prince- who hated the vice of drunkenness- poured a glass of brandy over the inebriated Sykes's head; the latter's only response was to bow and say "As your Royal Highness pleases". This performance was repeated subsequently, "dutifully obliged" by the "complicit" Sykes, to the sycophantic appreciation of courtiers present.[9]

However, Sykes's lavish entertainment of the Marlborough House Set - and the Prince of Wales - "dissipated much of his fortune".[8] In the late 1880s he was compelled to take out large loans which led to a long-running dispute with his solicitor and parliamentary agent eventually settled in the Court of Chancery.[10] Brantingham Thorpe was let from 1887.[11] The estate in which he held a life interest reverted on his death to trustees of his father who sold it in 1899 to the then tenant of the house.[12] Despite this, the Prince of Wales never forgot his devoted friend, and after Sykes' death in 1898, he installed a tablet to his memory at Westminster Abbey. Ridley observes of his near-bankruptcy in attendance on the Prince that "if Sykes was a victim, Bertie was an unwitting oppressor; he had nothing but pity for his old friend, he visited him in London and he wrote to Tatton Sykes imploring him to provide for his brother";[13] previously, the Prince, having for years stayed with Sykes for the Doncaster races, chose to stay elsewhere in consideration of Sykes's reduced circumstances, saying "I do not wish him... to spend a farthing on my account- I shall be furious if he gives me a birthday present!"[8]

References and sources

- "Personal". Illustrated London News. 24 December 1898. p. 945.

- The Times (1898), p. 8.

- Debretts House of Commons and the Judicial Bench 1886

- Dictionary of National Biography

- "Sykes, Christopher (SKS848C)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- Pellegrini, Carlo (14 November 1874). "The Gull's friend". Vanity Fair (UK magazine). Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- Ridley (2012), pp. 117, 280 & 333.

- Ridley (2012), p. 280.

- Ridley (2012), p. 117.

- Yorkshire Evening Post, 15 December 1898, p.4

- Blackburn Standard, 3 September 1887, p.6

- Yorkshire Herald, 7 July 1899, p. 4.; Eastern Morning News, 13 July 1899, p. 5.

- Ridley (2012), p. 333, 334.

- "Obituary". The Times (35702). 17 December 1898. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- Ridley, Jane (2012). Bertie - A Life of Edward VII. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 978-0099575443.