Paper chromatography

Paper chromatography is an analytical method used to separate coloured chemicals or substances.[1] It is now primarily used as a teaching tool, having been replaced in the laboratory by other chromatography methods such as thin-layer chromatography (TLC).

paper chromatography | |

| Acronym | PC |

|---|---|

| Classification | Chromatography |

| Analytes | chromatography is a technique used for separation of the parts of a mixture of either gas or liquid solution |

| Other techniques | |

| Related | Thin layer chromatography |

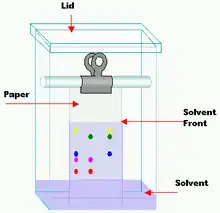

The setup has three components. The mobile phase is a solution that travels up the stationary phase by capillary action. The mobile phase is generally a mixture of non-polar organic solvent, while the stationary phase is polar inorganic solvent water. Here paper is used to support the stationary phase, water. Polar water molecules are held inside the void space of the cellulose network of the host paper. The difference between TLC and paper chromatography is that the stationary phase in TLC is a layer of adsorbent (usually silica gel, or aluminium oxide), and the stationary phase in paper chromatography is less absorbent paper.

A paper chromatography variant, two-dimensional chromatography, involves using two solvents and rotating the paper 90° in between. This is useful for separating complex mixtures of compounds having similar polarity, for example, amino acids.

Rƒ value, solutes, and solvents

The retention factor (Rƒ) may be defined as the ratio of the distance travelled by the solute to the distance travelled by the solvent. It is used in chromatography to quantify the amount of retardation of a sample in a stationary phase relative to a mobile phase.[2] Rƒ values are usually expressed as a fraction of two decimal places.

- If Rƒ value of a solution is zero, the solute remains in the stationary phase and thus it is immobile.

- If Rƒ value = 1 then the solute has no affinity for the stationary phase and travels with the solvent front.

For example, if a compound travels 9.9 cm and the solvent front travels 12.7 cm, the Rƒ value = (9.9/12.7) = 0.779 or 0.78. Rƒ value depends on temperature and the solvent used in experiment, so several solvents offer several Rƒ values for the same mixture of compound. A solvent in chromatography is the liquid the paper is placed in, and the solute is the ink which is being separated.

Pigments and polarity

Paper chromatography is one method for testing the purity of compounds and identifying substances. Paper chromatography is a useful technique because it is relatively quick and requires only small quantities of material. Separations in paper chromatography involve the principle of partition. In paper chromatography, substances are distributed between a stationary phase and a mobile phase. The stationary phase is the water trapped between the cellulose fibers of the paper. The mobile phase is a developing solution that travels up the stationary phase, carrying the samples with it. Components of the sample will separate readily according to how strongly they adsorb onto the stationary phase versus how readily they dissolve in the mobile phase.

When a colored chemical sample is placed on a filter paper, the colors separate from the sample by placing one end of the paper in a solvent. The solvent diffuses up the paper, dissolving the various molecules in the sample according to the polarities of the molecules and the solvent. If the sample contains more than one color, that means it must have more than one kind of molecule. Because of the different chemical structures of each kind of molecule, the chances are very high that each molecule will have at least a slightly different polarity, giving each molecule a different solubility in the solvent. The unequal solubility causes the various color molecules to leave solution at different places as the solvent continues to move up the paper. The more soluble a molecule is, the higher it will migrate up the paper. If a chemical is very non-polar it will not dissolve at all in a very polar solvent. This is the same for a very polar chemical and a very non-polar solvent.

It is very important to note that when using water (a very polar substance) as a solvent, the more polar the color, the higher it will rise on the papers.

Types

Descending

Development of the chromatogram is done by allowing the solvent to travel down the paper. Here, the mobile phase is placed in a solvent holder at the top. The spot is kept at the top and solvent flows down the paper from above.

Ascending

Here the solvent travels up the chromatographic paper. Both descending and ascending paper chromatography are used for the separation of organic and inorganic substances. The sample and solvent move upward.

Ascending-descending

This is the hybrid of both of the above techniques. The upper part of ascending chromatography can be folded over a rod in order to allow the paper to become descending after crossing the rod.

Circular chromatography

A circular filter paper is taken and the sample is deposited at the center of the paper. After drying the spot, the filter paper is tied horizontally on a Petri dish containing solvent, so that the wick of the paper is dipped in the solvent. The solvent rises through the wick and the components are separated into concentric rings.

Two-dimensional

In this technique a square or rectangular paper is used. Here the sample is applied to one of the corners and development is performed at a right angle to the direction of the first run.

History of paper chromatography

The discovery of paper chromatography in 1943 by Martin and Synge provided, for the first time, the means of surveying constituents of plants and for their separation and identification.[3] Erwin Chargaff credits in Weintraub's history of the man the 1944 article by Consden, Gordon and Martin.[4][5] There was an explosion of activity in this field after 1945.[3]

References

- "Paper chromatography | chemistry". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2018-06-01.

- IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "retention factor, k in column chromatography'". doi:10.1351/goldbook.R05359

- Haslam, Edwin (2007). "Vegetable tannins – Lessons of a phytochemical lifetime". Phytochemistry. 68 (22–24): 2713–21. doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.09.009. PMID 18037145.

- Consden, R.; Gordon, A. H.; Martin, A. J. P. (1944). "Qualitative analysis of proteins: A partition chromatographic method using paper". Biochemical Journal. 38 (3): 224–232. doi:10.1042/bj0380224. PMC 1258072. PMID 16747784.

- Weintraub, Bob (September 2006). "Erwin Chargaff and Chargaff's Rules". Chemistry in Israel - Bulletin of the Israel Chemical Society (22): 29–31.

Bibliography

- Block, Richard J.; Durrum, Emmett L.; Zweig, Gunter (1955). A Manual of Paper Chromatography and Paper Electrophoresis. Elsevier. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4832-7680-9 – via Google Books.