Cicero Hunt Lewis

Cicero Hunt Lewis (1826–1897) was a prominent merchant and investor in Portland in the U.S. state of Oregon during the second half of the 19th century. Born in New Jersey, Lewis and a friend, Lucius Allen, traveled across the continent in 1851 to open a dry goods and grocery store in what was then a frontier town of about 800 people living along the west bank of the Willamette River. By 1880, their firm, Allen & Lewis, had become one of the leading wholesale grocery companies on the West Coast.

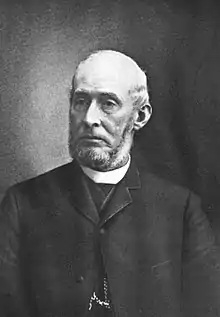

Cicero Hunt Lewis | |

|---|---|

C.H. Lewis | |

| Born | December 22, 1826 Cranbury, New Jersey, United States |

| Died | January 5, 1897 Portland, Oregon, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Merchant, investor |

| Spouse | Clementine Couch |

| Children | 11 |

| Relatives | John H. Couch, father-in-law |

Supporting transportation projects that affected his business, he was a member of the Portland River Channel Improvement Committee in the 1860s, invested in the Oregon Railway and Navigation Company in the 1870s, and was appointed to the original Port of Portland Commission in the 1890s. He helped form a local subscription library in the 1860s, and he was named to the city's first water board in the 1880s.

Married to Clementine Couch, daughter of another prominent Portland pioneer, Lewis fathered 11 children and after 1881 lived in a large, elegantly furnished house within walking distance of his office. He spent most of his time at work or at home, and had few other interests aside from church and charitable donations. He died in 1897 while walking to work on a Saturday afternoon.

Early life

Born in 1826 in Cranbury, New Jersey, Lewis moved with his parents at age 13 to Newburgh, New York. At age 20, he went to New York City to work in the dry-goods business of Chambers, Heiser & Company.[1]

Merchant-entrepreneur

John DeWitt, a New York merchant, hired Lewis in 1851 to assist DeWitt's son-in-law, Lucius Allen, in running a wholesale supply house in Portland, a frontier settlement on the West Coast.[2] Portland, with a population of about 800, was in good position to trade via the Willamette and Columbia rivers and the Pacific Ocean with San Francisco and other ports and by land with an increasing number of pioneer farmers in the Willamette Valley.[3] Allen, a friend of Lewis, had tried and failed in 1850 to establish a Portland branch store, and DeWitt thought that the more experienced Lewis would be able to help. In 1883 after several setbacks, the two men opened their own business (independent of New York) in a rented store at Front and "B" (Burnside) streets. They specialized in dry goods and groceries, building customer loyalty by selling at a fixed price, extending credit to reliable customers, and offering free space in their safe for storage of their customers' gold.[2]

By 1860, Allen had moved to San Francisco, a seaport city about 600 miles (970 km) south of Portland, where the company bought most of its supplies. He became a silent partner, uninvolved in day-to-day management. By then the firm of Allen & Lewis had begun to focus on wholesale markets, and by 1880, it was one of the leading wholesale grocery firms on the West Coast.[2] Lewis and three contemporaries, Henry W. Corbett, William S. Ladd, and Henry Failing, who arrived in Portland in 1851 and set up businesses along Front Street,[4] became "merchant princes of the Northwest".[5]

Within 10 years, this group of dedicated Front Street merchants and their families would dominate the economic, political and social life of Portland. All became warm and lasting friends with Ladd, the former teacher and railroad agent, first among equals... With Benjamin Stark and John H. Couch, who became Lewis's father-in-law, they formed Portland's earliest Establishment, one of merchant-entrepreneurs.[4]

In 1864, these four merchants and others formed the Portland River Channel Improvement Committee, to raise money to make the Willamette shipping channel more easily navigable. This led to a federally funded project by the United States Army Corps of Engineers, which dredged the channel in 1866.[6] In 1891, Lewis was named to the original Port of Portland Commission, established by the Oregon Legislative Assembly to oversee the maritime commercial and shipping interests of the city.[7]

When railroads began replacing steamships as a shipping method in the 1870s, Lewis, Ladd, Corbett, Failing, and Simeon Reed (a Portland transportation executive), became the five largest stockholders, aside from Henry Villard, in Villard's Oregon Railway and Navigation Company (OR&N).[8] In 1888, Lewis was part of a group that visited Villard in New York to negotiate favorable shipping rates on the Union Pacific and the Northern Pacific railroads, with which Villard and the OR&N had contracts affecting Portland.[9] Lewis's interest in Portland railroads extended to the Portland & Willamette Valley Railroad, of which he became a local director in 1885, and which was controlled and formally taken over by the Southern Pacific Railroad in 1890.[10]

Lewis and the other three pioneer merchants were among those in 1864 who formed the Mercantile Library Association (later renamed the Library Association of Portland) to establish a local subscription library. Roughly 30 years later, after a public library opened in Portland in 1891, members of the Cicero Lewis family were among its largest donors.[11] In 1885, Lewis was one of 15 men named to the Portland Water Committee, empowered by the state legislature to acquire and operate a municipal water system for the city.[12]

Family, other interests, death

In 1857 Lewis married Clementine Couch, daughter of John H. Couch, a sea captain and early Portland settler. Unlike many of his friends, Lewis developed few interests beyond his business. His only form of recreation was walking to work, and although he was a charter member of the Arlington Club and could have dined there, he usually walked home for lunch. Historian E. Kimbark MacColl writes that Lewis "spent his life at his desk and never went out in the evening for entertainment or the theater... He was never known to have taken a pleasure trip, spending what remaining leisure time he had with his wife and 11 children."[13] Lewis died of a stroke in 1897 while walking back to work on a Saturday afternoon.[13]

Lewis was a member of the Episcopal Church[14] and a Mason.[15] He was one of the largest supporters of Good Samaritan Hospital and Trinity Episcopal Church in Portland.[13] After Lewis died, his wife funded a hospital addition named in his honor at Good Samaritan.[1]

The Lewis family lived in a house on Fourth and Everett streets until 1881, when they built a large house on a lot in the Couch tract in northwest Portland. The tract, consisting of half of the block between 19th and 20th streets and Everett and Flanders streets, was owned by Mary Couch, Clementine's sister, and was developed by other members of the Couch family.[n 1] The project consisted of four houses, each on a lot 100 feet (30 m) wide and 100 feet (30 m) long.[5] The Lewis property, facing 19th Street, included stables, a greenhouse, and a sweeping drive leading to a carriage porch. Their very large house was built in a stick style that was "rather simple for its period", but its interior featured tall windows, a massive staircase, front and rear parlors, a reception room with a marble fireplace, and tall mirrors in elaborate frames, as well as "rare woods, marble mantels, brocaded walls [and] fine lighting fixtures" throughout.[5] The four houses on the Couch tract were demolished in the 1960s.[5]

Notes and references

Notes

- Central Portland lies on the west side of a bend in the north-flowing Willamette River. With few exceptions, its north–south streets (called avenues in the 21st century) are numbered in ascending order beginning west of Front Street (later named Naito Parkway), which runs along the river. In the northwest quadrant of the city, the east–west street names are alphabetical in ascending order beginning with Burnside Street. The first Lewis residence was roughly four blocks west of the river and three blocks north of Burnside, and their second residence was about 20 blocks west of the river and four blocks north of Burnside.[16]

References

- Gaston, pp. 106–09

- MacColl, Merchants, pp. 31–33

- Toll, William (2003). "The Oregon History Project: Foundings: Making a Market Town: Portland and Other Western Cities". Oregon Historical Society. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- MacColl, Merchants, p. 20

- Marlitt, pp. 29 and 58–65

- MacColl, Merchants, p. 154

- MacColl, Shaping, p. 421

- MacColl, Shaping, pp. 42–44

- MacColl, Shaping, p. 46

- MacColl, Shaping, pp. 70–73

- MacColl, Merchants, pp. 194–96

- MacColl, Merchants, p. 246

- MacColl, Shaping, pp. 26–29

- MacColl, Merchants, p. 312

- MacColl, Merchants, p. 189

- Streets of Portland (Map). Rand McNally. 2007. ISBN 0-528-86776-8.

Works cited

- Gaston, Joseph (1911). Portland, Oregon, its history and builders: in connection with the Antecedent Explorations, Discoveries, and Movements of the Pioneers That Selected the Site for the Great City of the Pacific, vol. 2. Chicago, Illinois: The S.J. Clarke Publishing Company.OCLC 1183569. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- Marlitt, Richard. (1978) [1968]. Seventeenth Street, revised ed. Portland, Oregon: Oregon Historical Society. ISBN 0-87595-000-0.

- MacColl, E. Kimbark; Stein, Harry H. (1988). Merchants, Money, and Power: The Portland Establishment 1843–1913. Portland, Oregon: The Georgian Press. ISBN 0-9603408-4-X.

- MacColl, E. Kimbark. (1976). The Shaping of a City: Business and Politics in Portland, Oregon, 1885 to 1915. Portland, Oregon: The Georgian Press. OCLC 2645815.