Cigar Makers' International Union

The Journeymen Cigar Makers' International Union of America (CMIU) was a labor union established in 1864 that represented workers in the cigar industry. The CMIU was part of the American Federation of Labor from 1887 until its merger in 1974.

Organizational history

Forerunners

The first local Cigar Makers' Union was founded in Baltimore, Maryland in 1851 by craftsmen who were opposed to the importation of low-cost laborers from Germany.[1] This was followed two or three years later by the establishment of a New York Cigarmakers' Union of about 70 members, mostly emigrants from England or Germany. This group quickly expanded in size to include about 160 of the city's 800 or so cigar workers before collapsing in an unsuccessful strike to avert a general cut in wages.[1]

The defeat proved temporary, as in 1859 another New York union was established in response to complaints about the business behavior of one manufacturer named Tom Little. About 250 cigarmakers were brought into the union before it, too, collapsed in a failed strike 10 months later.[1]

Part of the reason for the failure of cigar maker strikes was the lack of concentration of the industry. Prior to the American Civil War of 1861-1865, cigar makers were typically independent proprietors. Before 1889, all cigars were made by hand. The cigar roller or craftsman worked for himself, buying tobacco in small quantities as he needed it, using only his hands and a cutting blade to fabricate finished cigars in the place in which he lived.[2]

Samuel Gompers, himself a skilled cigar maker, echoed similar sentiments in his memoirs:

"In every community where the demand for cigars was sufficient to warrant, the cigar maker worked and sold his own cigars direct to the consuming public. Rarely did he employ helpers and then not more than one or two journeymen. If the journeyman became dissatisfied for any reason, he needed but small capital to become his own employer."[3]

In New York City, one of the leading hubs of cigar production in the 1860s, it was typical for cigar manufacturers to furnish the raw material to the cigar makers they employed, who would pay a deposit of nearly double the value of the tobacco supplied. The cigar makers would then carry their stock home and make the cigars in their own rooms, bringing back completed cigars to the manufacturer for payment.[4] Defects in workmanship would result in the manufacturer refusing to take the cigars, which would be left in the possession of the cigarmaker to dispose of as he was best able.[4]

During the Civil War, the revenue-starved federal government instituted an internal revenue tax on cigars and established a system of permits for employers and employees.[4] As the tax system tightened its embrace, this system of so-called "turn-in jobs" was eliminated; henceforth the employer would have to have some sort of physical facility. Many previously self-employed cigar makers were consequently driven out of business, forced to work in the employ of bonded cigar manufacturers. This accelerated the trend towards unionization of the industry.

Foundation

In 1863 came the first effort to establish a national union of cigar makers, bringing delegates from New York, Philadelphia, Newark, Cleveland, New Haven, Boston, Detroit, and elsewhere to a preliminary convention in Philadelphia.[1] This gathering decided to move forward with the establishment of a national union and called a foundation convention for the group for June 21, 1864, in New York City.[1]

The union formed at this New York meeting was initially known as the National Union of Cigar Makers of America, before changing its name to the Journeymen Cigar Makers' International Union (CMIU) in 1867.[5]

One of the early challenges faced by the CMIU related to a new system of manufacture established in the first years of the 1870s. The years 1871 and 1872 saw the arrival of a substantial wave of immigrants from Bohemia, a region which now comprises the western two-thirds of the Czech Republic. This new group of arrivals provided manufacturers with a ready source of low-cost labor. A simplified system of cigar production was also emerging at the same time, assisted by the appearance in 1867 of a wooden mold or form, which decreased assembly time during the bunching process by eliminating one step in the manufacture of cigars by hand.[6] Cigar manufacturers, seeking to realize larger profits from economies of scale using the new assembly methods would buy or rent a block of tenements and then sublet the apartments to cigar makers and their families — thereby technically fulfilling the government requirement of maintaining a physical facility.[7]

Traditional craft skill was thus devalued and the cigar makers demoralized. High union initiation fees further limited the size of the unionized workforce. English-speaking Local 15 of the CMIU in New York City evaporated to fewer than 50; German-speaking Local 90 to just 85; and the union as a whole to only 3,771 members in 1873.[7]

The CMIU concentrated its efforts on publicizing the abuses inherent in the so-called "tenement house system," ultimately forcing the New York Board of Health to take notice of the situation. The report of the Board of Health whitewashed the tenement system, making it seem as though the tenements represented superior living quarters, an action which enraged the unionized cigar makers and mobilized other unions of the city to the cigar makers' cause.[8]

Development

The economic crisis of 1877 was very nearly fatal to the organization, with a coordinated lockout by the employers' association of cigar manufacturers putting 7,000 workers out on the street in a lockout lasting four months.[1] Only 131 of the union's approximately 6,000 members remained in the union after the strike and the CMIU did not again exceed the 1,000 member mark until a full year later.[1]

The CMIU was instrumental in the formation of the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions in 1881, and organization which later evolved into the American Federation of Labor (AF of L).

The years 1879 to 1883 were a period of dramatic growth, with the number of union locals increasing from 35 to 185, with about 10,000 members.[1]

In 1882, bitter disagreement over the question of political endorsements lead to a split of the union, with about 1,800 New York City cigarmakers seceding to form the Cigarmakers' Progressive Union of America.[1] Many of the members of this new organization were members of the Socialist Labor Party of America and were unwilling to see the national union work hand-in-glove with established, sometimes corrupt, politicians of the Democratic and Republican parties.[1] The two sibling unions were in a position of competing with one another and they engaged in a bitter and destructive four year war, undercutting one another's contracts in order to gain recognition, until they once again reunited in 1886. This is a well-studied example of the dual unionism problem.[9]

The American Federation of Labor chartered the Cigar Makers in 1887. George W. Perkins became president of the CMIU in 1892, a post he held until 1927. Perkins disdain for machine-made cigars and manufacture was reflected in his dogged refusal to extend CMIU membership to the semi-skilled and unskilled workers employed in machine cigar factories throughout his term as president.

As of 1925, the CMIU included 13,463 men and 3,186 women out of an American national work force in the industry of 28,293 men and 50,648 women.[10] Of some 10,320 cigar-making shops known to the union, an impressive 7,180 used union labor, but of these 3,246 consisted of shops in which the owner was the only worker employed.[10]

Ideology

Although the Cigar Makers' Union initially barred black and female cigar makers from membership at its 2nd National Convention, held in Cleveland, Ohio in 1865, it reversed this decision two years later and came to be a forerunner in the representation of workers of various ethnic backgrounds.[1] The Cigar Makers' International Union in 1867 became one of only two national unions to accept females to membership.[11] This policy was sometimes openly defied by union locals, however.

While the CMIU pressed for higher wages, shorter hours, better working conditions, and the right of collective bargaining, it restricted its organizing efforts to the skilled cigar roller or craftsman, requiring factory owners to reject any production of cigars by machine or to use non-union semi-skilled or unskilled labor, i.e. a closed shop.

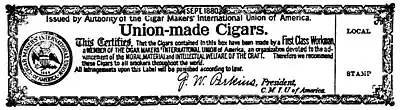

Union labels

After 1880, Cigar manufacturers who negotiated labor contracts with the CMIU affixed blue labels to boxes of "union made" cigars made exclusively by a "First-Class Workman", i.e. hand-made. Previously, local chapters issued their own stamps including white labels, used by the Cigar Makers' Association of the Pacific Coast to show that their cigars were made by white labor, in response to the growing use of low-wage, Chinese immigrant labor. In 1875, the cigar makers' local in St Louis tried to encourage consumers to buy union-made cigars by using a red label.

The CMIU created a standard blue "union made" label in 1880 to reflect the fact that the cigars inside were made by a skilled labor union member. Union stamps underwent frequent changes and are an excellent help to collectors in the dating of cigar boxes. A "Sept. 1880" date was added top center to the label design in 1888 and appears on all CMIU cigar (not stogie) issues until 1974.

Decline and merger

About one-half of all cigar workers were represented by the CMIU in 1916, when its membership peaked at 53,000 members.[12]

In the end, the decisive blow to cigar maker unions came from technology and changing consumer preferences. As early as 1880, continued strikes, walkouts, and the steadily rising costs of labor and tobacco leaf caused U.S. tobacco companies to invest in mechanized methods of producing cigarettes and cigars. The first cigarette rolling machine was introduced in 1880 by James Albert Bonsack, while the cigar-making machine first appeared in 1889.[13][14] As demand for cigarettes increased, consumption of hand-rolled cigars declined, which directly affected CMIU members. Mechanization and unskilled cigar workers (known as "bunch breakers") increasingly replaced skilled cigar workers after World War I. Strangely, George Perkins and the CMIU leadership declined to organize semi-skilled and unskilled machine workers despite overwhelming evidence that traditional cigar-making was in steep decline; an estimated 56,000 jobs were lost between 1921 and 1935.[15] Scores of union factories went out of business, while the remainder declared an open shop.[16] By 1928, the CMIU lost much of its influence; the average CMIU member was now sixty-four years old.[17] In that year, CMIU's leadership finally agreed to unionize machine cigar workers and permit the union label on machine-finished cigars, but it was too late.[18] The Great Depression resulted in additional industry cost-cutting. By 1933, CMIU membership had declined to 15,000 members, many of them unemployed.[18] In 1931, the American Cigar Co., the only USA-based cigar factory still using hand-rolling techniques, ceased manufacture.[19]

After World War II, the consolidation of cigar manufacturing in the United States continued; many of the remaining larger manufacturing concerns moved cigar production to Central America and South America, which only accelerated the loss of union jobs.[20]

In 1974, the remaining 2,000 members of the CMIU voted to merge with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union.[12][21]

Notable members

Presidents

- 1864: Andrew Zeitler

- 1865: L. C. Walker

- 1867: John J. Junbo

- 1868: Fred Bland

- 1871: Edwin Johnson

- 1872: William H. Noerr

- 1873: William J. Cannon

- 1875: George Hurst

- 1877: Adolph Strasser

- 1891: George W. Perkins

- 1927: Ira M. Ornburn

- 1936: R. E. Van Horn

- 1944: A. P. Bower

- 1949: Mario Azpeitia

Other members

- J. Mahlon Barnes, Executive Secretary of the Socialist Party of America

- John J. Ballam, Communist Party Central Executive Committee member and union organizer

- Samuel Gompers, longtime President of the AF of L, was a National Vice President of the CMIU and President of Local 144

- John Kirchner, Secretary of the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions

Footnotes

- "Cigar-Makers! Interesting History of Their Organization," The People [New York], vol. 1, no. 25 (September 20, 1891), pg. 1.

- John B. Andrews, "The Cigar Makers," in John R. Commons, et al., History of Labour in the United States. New York: Macmillan, 1918; vol. 2, pg. 69.

- Samuel Gompers, Seventy Years of Life and Labor: An Autobiography. New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1925; vol. 1, pp. 106-107.

- Gompers, Seventy Years of Life and Labor, vol. 1, pg. 107.

- Andrews, "The Cigar Makers," History of Labour in the United States, vol. 2, pg. 70.

- Andrews, "The Cigar Makers," History of Labour in the United States, vol. 2, pg. 71.

- Gompers, Seventy Years of Life and Labor, vol. 1, pg. 108.

- Gompers, Seventy Years of Life and Labor, vol. 1, pg. 113.

- East, Dennis (1975-03-01). "Union labels and boycotts: Cooperation of the knights of labor and the cigar makers international union, 1885–6". Labor History. 16 (2): 266–271. doi:10.1080/00236567508584336. ISSN 0023-656X.

- "Cigarmakers' International Union of America," in Solon DeLeon and Nathan Fine (eds.), The American Labor Year Book 1926. New York: Rand School of Social Science, 1926; pp. 161-162.

- Alice Henry, The Trade Union Woman. Library of Congress. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- "Archives of the Cigar Makers' International Union". University of Maryland Libraries. 2007. Archived from the original on 2012-06-22. Retrieved 2012-03-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Tilley, N. M.: The Bright-tobacco industry, 1860 - 1929; Arno Press (1972), ISBN 0-405-04728-2

- The Wheeling Intelligencer, A Great Invention, Wheeling, W. VA 25 July 1889, p. 1

- Lerman, N. (ed.) Gender and Technology: A Reader, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801872596 (2003),pp. 221

- Lerman, N. (ed.) Gender and Technology: A Reader, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801872596 (2003),pp. 221, 225

- Lerman, N. (ed.) Gender and Technology: A Reader, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801872596 (2003),pp. 226

- Lerman, N. (ed.) Gender and Technology: A Reader, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801872596 (2003),p. 225

- United States Tobacco Journal, 16 February 1931

- Lerman, N. (ed.) Gender and Technology: A Reader, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801872596 (2003),pp. 228

- Lerman, N. (ed.) Gender and Technology: A Reader, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801872596 (2003),p. 228

Further reading

- Patricia A. Cooper, Once a Cigar Maker: Men, Women, and Work Culture in American Cigar Factories, 1900-1919. Urbana: Illinois University Press, 1987.

- G.W. Perkins (ed.), Cigar Makers' Official Journal. Volumes 33 to 36. Chicago: Cigar Makers' International Union of America, 1908-1911.

- G.W. Perkins (ed.), Cigar Makers' Official Journal. Volumes 42 to 44. Chicago: Cigar Makers' International Union of America, 1918-1920.

- G.W. Perkins (ed.), Cigar Makers' Official Journal. Volumes 45 to 47. Chicago: Cigar Makers' International Union of America, 1921-1923.

External links

- Tony Hyman, "Dating Union-Made Labels," National Cigar Museum. Retrieved April 29, 2010. —Color illustrations of CMIU labels, 1880-1974.

- Cigar Makers' International Union Collection. 1856-1974. 30 reels of microfilm and 5.50 linear feet. University of Maryland Labor History Collection, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Maryland Libraries.

- Patricia Cooper's collection of papers includes papers, photographs, and manuscript drafts among others concerning her book Once a Cigar Maker: Men, Women, and Work Culture in American Cigar Factories, 1900-1919 located at the University of Maryland Libraries.