Cimarron River (Arkansas River tributary)

The Cimarron River (/ˈsɪmərɒn, -roʊn/ SIM-ə-ro(h)n; Iowa-Oto: Ñíxgu or Ñíhgu, meaning 'Salt River';[4] Cheyenne: Hotóao'hé'e) extends 698 miles (1,123 km) across New Mexico, Oklahoma, Colorado, and Kansas. The headwaters flow from Johnson Mesa west of Folsom in northeastern New Mexico. Much of the river's length lies in Oklahoma, where it either borders or passes through eleven counties. There are no major cities along its route. The river enters the Oklahoma Panhandle near Kenton, Oklahoma, crosses the corner of southeastern Colorado into Kansas, reenters the Oklahoma Panhandle, reenters Kansas, and finally returns to Oklahoma where it joins the Arkansas River at Keystone Reservoir west of Tulsa, Oklahoma, its only impoundment. The Cimarron drains a basin that encompasses about 18,927 square miles (49,020 km2).[5]

| Cimarron River | |

|---|---|

The Cimarron River, near Forgan, Oklahoma | |

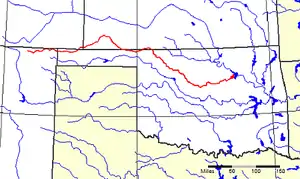

Map of the Arkansas River basin with the Cimarron River highlighted. | |

| Etymology | Río de los Carneros Cimarrones (Spanish for 'River of the Wild Sheep') |

| Native name | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma |

| Cities | Cushing, Oklahoma, Mannford, Oklahoma, Guthrie, Oklahoma |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Confluence of Dry Cimarron River and Carrizozo Creek |

| • location | Kenton, Cimarron County, Oklahoma |

| • coordinates | 36°54′24″N 102°59′12″W[1] |

| • elevation | 4,318 ft (1,316 m) |

| Mouth | Arkansas River |

• location | Keystone Lake, at Westport, Pawnee County, Oklahoma |

• coordinates | 36°10′14″N 96°16′19″W[1] |

• elevation | 722 ft (220 m) |

| Length | 698 mi (1,123 km) |

| Basin size | 18,950 sq mi (49,100 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Guthrie, Oklahoma, 65 miles (105 km) from the mouth[2] |

| • average | 1,163 cu ft/s (32.9 m3/s)[3] |

| • minimum | 0.3 cu ft/s (0.0085 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 158,000 cu ft/s (4,500 m3/s) |

Names and etymology

The river's present name comes from the early Spanish name, Río de los Carneros Cimarrones, which is usually translated as 'River of the Wild Sheep'; previous English names for the river include Grand Saline, Jefferson (in John Melish's 1820 U.S. map), Red Fork, and Salt Fork.[5]

Description

In northeastern New Mexico and in far western Oklahoma, the river is known as the Dry Cimarron River. The Dry Cimarron is not completely dry, but sometimes its water entirely disappears under the sand in the river bed. The Dry Cimarron Scenic Byway follows the river from Folsom to the Oklahoma border. The waterway becomes simply the Cimarron River after being joined by Carrizozo Creek just inside the Oklahoma border, west of Kenton, Oklahoma.[6] Carrizozo Creek also originates in New Mexico and exits into Oklahoma before re-entering New Mexico and then returning to Oklahoma before joining the river.[6]

In Oklahoma it is further joined by North Carrizo Creek north-northeast of Kenton, Tesesquite Creek further to the east of Kenton, and South Carrizo Creek yet further to the east.[6] It additionally joins with Cold Springs Creek, Ute Canyon Creek, and Flagg Springs Creek before crossing into Kansas.[6] The river flows along the southern edges of Black Mesa, Oklahoma's highest point. As it first crosses the Kansas border, the river flows through the Cimarron National Grassland.

At Guthrie, the river is joined by Cottonwood Creek (Cimarron River tributary), at a site known for frequent flooding.[7][8][9]

The Cimarron's water quality is rated as poor because the river flows through natural mineral deposits, salt plains, and saline springs, where it dissolves large amounts of minerals.[5] It also collects quantities of red soil, which it carries to its terminus. Before the Keystone Dam was built, this silt was sufficient to discolor the Arkansas River downstream.

Early explorers

The first Europeans to see the Cimarron River were apparently Spanish conquistadores led by Francisco Vásquez de Coronado in 1541. The Spanish seem to have done little to exploit the area. The Osage tribe claimed most of the territory west of the confluence of the Cimarron and the Arkansas. In 1819 Thomas Nuttall explored the lower Cimarron and wrote a report describing the flora and fauna that he found there. In 1821 Mexico threw off Spanish rule and William Becknell opened the Santa Fe Trail.[5]

Historical notes of interest

- One branch of the Santa Fe Trail, known variously as the Cimarron Route, the Cimarron Cutoff, and the Middle Crossing (of the Arkansas River), ran through the Cimarron Desert and then along the Cimarron River.[10]: 144, 148 Lower Cimarron Spring on the riverbank was an important watering and camping spot.[11]

- In 1831 Comanche Indians killed Jedediah Smith (a famous hunter, trapper, and explorer) on the Santa Fe Trail near the Cimarron River. His body was never recovered.[12]

- In 1834 General Henry Leavenworth established Camp Arbuckle (Fort Arbuckle) at the mouth of the Cimarron River.[5] Later known as Old Fort Arbuckle, it was active for only about a year, and its former site is now submerged beneath the Arkansas River. It should not be confused with the later Fort Arbuckle in Garvin County, Oklahoma.[lower-alpha 1]

- Historic sites along the river include the ruins of Camp Nichols, a stone fort Kit Carson built in 1865 to protect travelers from raids by Plains Indians on the Cimarron Cutoff. It was near present-day Wheeless, Oklahoma.[lower-alpha 2]

- The old Chisholm Trail crossed the river at Red Fork Station near present-day Dover, Oklahoma.

- In the 1890s the Creek Nation Cave along the Cimarron River near Ingalls in the Oklahoma Territory, was a hideout for the Doolin gang, which included the teenage bandits Cattle Annie and Little Britches.[13]

- On September 18, 1906, a bridge across the Cimarron near Dover, Oklahoma Territory, collapsed beneath a Rock Island train bound for Fort Worth, Texas from Chicago. The bridge was a temporary structure unable to withstand the pressure of debris and high water. The railroad had delayed replacing it with a permanent structure for financial reasons. Several sources report that over 100 people were killed,[14][15][16] but the figure is disputed. The true number may be as low as four.[17]

Notes

- See History section in Tulsa County, Oklahoma for further explanation of the creation of Old Fort Arbuckle.

- Wheeless is at the extreme western end of the Oklahoma Panhandle.

See also

References

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Cimarron River (Arkansas River tributary)

- "USGS Gage #07160000 on the Cimarron River near Guthrie, OK" (PDF). National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1938–2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- "USGS Gage #07160000 on the Cimarron River near Guthrie, OK" (PDF). National Water Information System. U.S. Geological Survey. 1938–2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 19, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2010.

- (2008) Kansas Historical Society, Ioway-Otoe-Missouria Language Project, English to Ioway-Otoe-Missouria Dictionary, "Dictionary X (English to Baxoje)", "Cimarron River". Link

- Larry O'Dell, "Cimarron River," Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Archived April 2, 2015, at the Wayback Machine Accessed March 6, 2015.

- "Carrizozo Creek near Kenton, OK". USGS. Retrieved September 9, 2020.

- "Floods in Guthrie, Oklahoma" US Army Corps of Engineers (1970) (Archived at LOC.gov, accessed Oct. 26, 2021)

- "Guthrie flooding keeps schools, roads closed" News9.com (May 22, 2019)

- "Recent flood ranks in top 10" GuthriesNewsPage.com (May 22, 2019)

- Stocking, Hobart (1971). The Road to Santa Fe. New York: Hastings House Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8038-6314-9.

- Whitacre, Christine; Steven De Vore (March 17, 1997). Patty Henry (ed.). "Lower Cimarron Spring National Historic Landmark Nomination USDI/NPS" (PDF). National Park Service. p. 36. Retrieved December 13, 2012.

- "Cimarron Cutoff". Santa Fe Trail Research Site. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- "Cattle Annie & Little Britches, taken from Lee Paul". ranchdivaoutfitters.com. Archived from the original on January 17, 2012. Retrieved December 27, 2012.

- Kite, Steven (September 20, 2000). "Corporate Greed Leads to Death in Oklahoma Territory". Oklahoma Audio Almanac. Oklahoma State University Library. Archived from the original on June 4, 2010. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- "Dover". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved May 18, 2010.

- Goins, Charles Robert; Goble, Danney (2006). Historical Atlas of Oklahoma. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-8061-3482-8.

- Sencicle, Lorraine (January 2008). "Dover Oklahoma". The Daughters of Dover: Dover around the world. Dover, England: The Dover Society. Archived from the original on September 21, 2010. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

Further reading

- Anshutz, Carrie W. Schmoker; M.W. (Doc) Anshutz. Cimarron Chronicles: Saga of the Open Range. Meade, Kansas: Ohnick Enterprises, 2003. ISBN 0-9746222-0-6

- Dary, David. The Santa Fe Trail: Its History, Legends, and Lore. New York: Penguin, 2002 (Reissue). ISBN 0-14-200058-2

- Hanners, Laverne; Ed Lord. The Lords of the Valley: Including the Complete Text of Our Unsheltered Lives. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8061-2804-6

- Hoig, Stan. Beyond the Frontier: Exploring the Indian Country. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8061-3052-0

- Schumm, Stanley A. Channel Widening and Flood-Plain Construction along Cimarron River in Southwestern Kansas: Erosion and Sedimentation in a Semiarid Environment. Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1963. ISBN B0007EFJLY

- Schumm, Stanley A. River Variability and Complexity. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-521-84671-4

- Stovall, John Willis. Geology of the Cimarron River Valley in Cimarron County, Oklahoma. Chicago, 1938.

- Woodhouse, S. W. (Eds. John S. Tomer, Michael J. Brodhead). A Naturalist in Indian Territory: The Journals of S.W. Woodhouse, 1849–50 (The American Exploration and Travel Series, Vol 72). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8061-2805-4

External links

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Cimarron River

- Santa Fe Trail Research Site

- Mouth of the Cimarron TopoQuest.

- Headwaters of the Cimarron TopoQuest.

- Cimarron National Grassland USDA Forest Service.

- Dry Cimarron Scenic Byway New Mexico Historic Markers.

- Kansas connections (Eco-History Trails and Tales)

- Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture – Cimarron River

- Oklahoma Digital Maps: Digital Collections of Oklahoma and Indian Territory