Cirta steles

The Cirta steles are almost 1,000 Punic funerary and votive steles found in Cirta (today Constantine, Algeria) in a cemetery located on a hill immediately south of the Salah Bey Viaduct.

.jpg.webp)

The first group of steles were published by Auguste Celestin Judas in 1861. The Lazare Costa inscriptions were the second group of these inscriptions found; they were discovered between 1875 and 1880 by Lazare Costa, a Constantine-based Italian antiquarian. Most of the steles are now in the Louvre.[2][3][4] These are known as KAI 102–105.

In 1950, hundreds of additional steles were excavated from the same location – then named El Hofra – by André Berthier, director of the Gustave-Mercier Museum (today the Musée national Cirta) and Father René Charlier, professor at the Constantine seminary.[5] Many of these steles are now in the Musée national Cirta.[6] Over a dozen of the most notable inscriptions were later published in Kanaanäische und Aramäische Inschriften and are known as 106-116 (Punic) and 162-164 (Neo Punic).

Judas steles

_-_Plate_11.jpg.webp)

_-_Plate_1.jpg.webp)

_-_Plate_3.jpg.webp)

_-_Plate_4.jpg.webp)

In 1861 Auguste Celestin Judas published a series of 19 inscribed steles in the Annuaire de la Société archéologique de la province de Constantine. Between 1857 and 61 more than 30 such steles had been collected by the Archaeological Society, of which a dozen in 1860 alone.[7] Judas noted that the locations of the finds had been difficult to ascertain, his understanding was as follows:[8]

Of the nineteen inscriptions of which I have spoken, two, nos. II and XVII, come from Coudiat-ati; sixteen from the location of the new Christian cemetery, to the west and 500 meters from Coudiat-ati, 725 meters from Constantine. For number I, no indication.

Costa steles

Overview

On the death of Lazare Costa, Antoine Héron de Villefosse and Dr Reboud negotiated the acquisition of all of Costa's steles for the Louvre. Although not all the steles made it to the Louvre, more were found.[9]

A concordance of 135 of the steles was published by Jean-Baptiste Chabot in 1917.[10]

Gallery

Lazare Costa's manuscript map showing the location of his discoveries

Lazare Costa's manuscript map showing the location of his discoveries

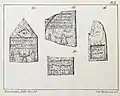

Inscriptions 4-6 (Costa 6 is RES 331)

Inscriptions 4-6 (Costa 6 is RES 331) Inscriptions 7-9 (Costa 8 is KAI 105 / RES 334 / KI 98 / NSI 51)

Inscriptions 7-9 (Costa 8 is KAI 105 / RES 334 / KI 98 / NSI 51) Inscriptions 10-12

Inscriptions 10-12 Inscriptions 13-15

Inscriptions 13-15 Inscriptions 16-18 (Costa 16 is RES 328, Costa 17 is RES 333)

Inscriptions 16-18 (Costa 16 is RES 328, Costa 17 is RES 333) Inscriptions 19-21

Inscriptions 19-21 Inscriptions 22-24 (Costa 22 is RES 330, and Costa 24 is RES 326)

Inscriptions 22-24 (Costa 22 is RES 330, and Costa 24 is RES 326) Inscriptions 25-31 (Costa 31 is KAI 104 / RES 327 / KI 97)

Inscriptions 25-31 (Costa 31 is KAI 104 / RES 327 / KI 97) Inscriptions 32-35 (Costa 33 is RES 329)

Inscriptions 32-35 (Costa 33 is RES 329) AO 5226 on display at the Louvre

AO 5226 on display at the Louvre AO 5187 on display at the Louvre

AO 5187 on display at the Louvre AO 5191 on display at the Louvre

AO 5191 on display at the Louvre%252C_around_300-200_BC%252C_Louvre_Lens%252C_France_(26329653164).jpg.webp) "Costa 15" in the Louvre-Lens

"Costa 15" in the Louvre-Lens Costa 16 on display at the Musée d'archéologie méditerranéenne, Marseille

Costa 16 on display at the Musée d'archéologie méditerranéenne, Marseille

Berthier steles

.jpg.webp)

Overview

At the southern exit of the city, on the El Hofra hill, about 150m southeast of what was then the "Transatlantic Hotel" (today a branch of the Crédit populaire d'Algérie), the construction of a large Renault garage (today Garage Sonacome) was begun in spring 1950.[5] The hill is at the confluence of the Rhumel River and its tributary Oued Bou Merzoug, just south of the Salah Bey Viaduct. On May 6, 1950, the excavator struck a mass of stelae grouped over a length of about 75m, laid flat and forming a kind of wall whose height did not exceed the thickness of four stelae while the width varied from 0.5-1.0m.[6]

The stelae were not found in situ: all appear to have been broken with intention (all were broken and many of the inscriptions were mutilated), and then transported to a sort of dumping ground.[11]

By September 1950, about 500 fragments had been found, more than half of which bearing inscriptions;[6] in total 700 stelae and fragments were found, of which 281 were Punic and neo-Punic stelae, totally or partially legible, 17 were Greek inscriptions and 7 were Latin inscriptions.[5] Almost all the steles were published by Berthier and Charlier, except for three – one long Punic inscription which was too faint, and two Neo Punic inscriptions which were later published by James Germain Février (KAI 162–163).[12]

Some are dated to the reign of Massinissa or the reign of her sons; they range from 163-2 BCE until 148-7 (the year of Massinissa's death) and perhaps until 122-1 (under Micipsa). Number 63 (KAI 112) mentions the simultaneous reign of the three sons of Massinissa – Micipsa, Gulussa and Mastanabai, and one of the stelae contains a complete transliteration of a Punic text in Greek characters (page 167).[5]

Bibliography

- BERTHIER André - CHARLIER René, 1952–55, Le sanctuaire punique d'El-Hofra à Constantine. 2 volumes

- Février, James Germain [in French] (1955). "Review: Le sanctuaire punique d'El Hofra à Constantine, par André Berthier et René Charlier. Préface d'Albert Grenier, membre de l'Institut, 1955". Revue des Études Anciennes. 57 (3–4): 410–412.

- Bertrandy François, Sznycer Maurice, Les Stèles puniques de Constantine, musée du Louvre, département des Antiquités orientales, Paris, Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1987.

- MacKendrick, P.L. (2000). The North African Stones Speak. University of North Carolina Press. p. 194. ISBN 978-0-8078-4942-2.

References

- pages 433-434

- Punic stele with triangular pediment: "Dating from the 2nd century BC, this votive stele was discovered in Algeria in 1875, together with some hundred others, by Lazare Costa, an Italian antiquarian from Constantine. An enthusiastic amateur archaeologist, Costa visited all the civil engineering sites and agricultural development projects in Constantine and its environs. Thus it was that on the slopes of the hill of el-Hofra - then being prepared for the planting of a vineyard - he discovered the greater part of these monuments, today in the Louvre."

- Cahen, Abr. (1879). Inscriptions Puniques et Neo-Puniques de Constantine. Alessi et Arnolet., Recueil des notices et mémoires de la Société Archéologique du Département de Constantine, volume 19, 1878, pages 252 onwards and plates

- V Reboud, Quelques Mots sur les Steles Neo Puniques Découvertes par Lazare Costa, Recueil des notices et mémoires de la Société Archéologique du Département de Constantine, volume 18, 1877, pages 434 onwards, and plates

- Février 1955.

- Grenier Albert. Nouvelles archéologiques d'Algérie. In: Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, 94e année, N. 4, 1950. pp. 345-354. DOI : https://doi.org/10.3406/crai.1950.78583

- Auguste Celestin Judas, 1861, Inscriptions Numidico-Puniques Découvertes a Constantine, Annuaire de la Société archéologique de la province de Constantine 1860-61, Société archéologique, historique et géographique du département de Constantine: "Dans le cours des quatre dernières années seulement, plus de trente pierres avec des inscriptions ou des anaglyphes numidico-puniques ont été découvertes dans l'antique capitale de Massinissa. Plusieurs des inscriptions apportent, si je ne me trompe, un nouveau jour à l'étude de la langue introduite par les Carthaginois... En novembre 1860, une nouvelle trouvaille a eu lieu; elle comprenait une douzaine de pierres.... Les textes qui m'ont paru, à l'aide de ces instruments, susceptibles de lecture sont au nombre de dix-neuf; des copies, les unes réduites, les autres de grandeur réelle, en sont présentées aux plancbes I à IX."

- Auguste Celestin Judas, 1861, Inscriptions Numidico-Puniques Découvertes a Constantine, Annuaire de la Société archéologique de la province de Constantine 1860-61, Société archéologique, historique et géographique du département de Constantine: p.89 "Des dix-neuf inscriptions dont j'ai parlé,-deux, les nos II et XVII, proviennent dû Coudiat-ati; seize de l'emplacement du nouveau cimetière chrétien, à l'ouest et à 500 mètres du Coudiat-ati, à 725 mètres de Constantine. Pour le n° I, nulle indication."

- Les Inscriptions de Constantine au Musee de Louvre par Philippe Berger, Actes du onzième congrès international des Orientalistes. Paris, 1897. Section 4 Congrès international des orientalistes, 1897, p.273 onwards: "A la mort de M. Costa, M. Héron de Villefosse, aidé du Dr Reboud, dont le nom restera attaché à l'épigraphie de Constantine, négocia l'acquisition de toutes les stèles de Costa pour le Musée du Louvre. Un certain nombre d'entre elles, sans doute déjà dispersées auparavant, ne sont pas parvenues au Musée du Louvre. D'autre part, la collection du Louvre s'est enrichie de quelques stèles qui ne figurent pas parmi les estampages de M. Costa, et d'une vingtaine d'autres provenant du moulin Carbonel et données par le Dr Reboud. Telle qu'elle est, la collection des inscriptions de Constantine, qui ne comprend pas moins de 150 numéros, forme, après Carthage et Maktar, la série la plus complète des inscriptions phéniciennes d'Afrique. Ces inscriptions paraîtront à leur place dans le Corpus; je voudrais dès à présent appeler l'attention sur quelques particularités communes à cette série épigraphique, l'une des plus intéressantes par son unité, comme aussi par certains caractères qui lui assignent une place à part dans l'épigraphie punique."

- Chabot, Jean-Baptiste (1917). Punica: XVIII Steles Punique de Constantine; II. Collection Costa. Journal asiatique. Société asiatique. pp. 50–72.

- Février 1955, p. 410-411: "Les stèles n'ont pas été trouvées in situ: brisées toutes avec intention, elles avaient été transportées ensuite dans une sorte de terrain de décharge.... Toutes les stèles étaient brisées et sur beaucoup l'inscription mutilée."

- Février 1955, p. 411: "Trois textes ne figurent pas dans la publication. L'un est une longue inscription punique, à peu près évanide. Les deux autres sont néo-puniques : la lecture matérielle en est aisée, l'interprétation difficile ; je viens de les éditer, avec l'autorisation de MM. Berthier et Charlier, dans les Mélanges Isidore Lévy."