City status in Ireland

In Ireland, the term city has somewhat differing meanings in Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

City in Northern Ireland:

City in Northern Ireland:- City in the Republic of Ireland:

Administrative unit termed a "city"

Administrative unit termed a "city" City within "city and county" administrative unit

City within "city and county" administrative unit Ceremonial city within "county" administrative unit

Ceremonial city within "county" administrative unit

Former city (status lost before partition)

Former city (status lost before partition)

Historically, city status in the United Kingdom, and before that in the Kingdom of Ireland, was a ceremonial designation. It carried more prestige than the alternative municipal titles "borough", "town" and "township", but gave no extra legal powers. This remains the case in Northern Ireland, which is still part of the United Kingdom. In the Republic of Ireland, "city" has an additional designation in local government.

History up to 1920

Before the Partition of Ireland in 1920–22, the island formed a single jurisdiction in which "city" had a common history.

The first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary s.v. city (published 1893), explains that in England, from the time of Henry VIII, the word was applied to towns with Church of England cathedrals. It goes on to say:

The history of the word in Ireland is somewhat parallel. Probably all or most of the places having bishops have been styled on some occasion civitas; but some of these are mere hamlets, and the term 'city' is currently applied only to a few of them which are ancient and important boroughs. Thom's Directory applies it to Dublin, Cork, Derry, Limerick ('City of the violated treaty'), Kilkenny, and Waterford; also to Armagh and Cashel, but not to Tuam or Galway (though the latter is often called 'the City of the Tribes'). Belfast was, in 1888, created a 'city' by Royal Letters Patent.

Cathair

In most European languages, there is no distinction between "city" and "town", with the same word translating both English words; for example, ville in French, or Stadt in German.

In Modern Irish, "city" is translated cathair[1] and "town" is translated baile;[2] however, this is a recent convention; previously baile was applied to any settlement,[3] while cathair meant a walled or stone fortress, monastery, or city; the term was derived from Proto-Celtic *katrixs ("fortification").[4] For example, Dublin, long the metropolis of the island, has been called Baile Átha Cliath since the fifteenth century,[5] while its earliest city charter is from 1172.[6] The Irish text of the Constitution of Ireland translates "city of Dublin" as cathair Bhaile Átha Chliath,[7] combining the modern sense of cathair with the historic sense of Baile. Conversely, the original Irish names of such smaller settlements as Cahir, Cahirciveen, Caherdaniel, or Westport (Cathair na Mart) use cathair in the older sense.

Civitas

In the Roman Empire, the Latin civitas referred originally to the jurisdiction of a capital town, typically the territory of a single conquered tribe.[8] Later it came to mean the capital town itself.[8] When Christianity was organised in Gaul, each diocese was the territory of a tribe, and each bishop resided in the civitas.[8] Thus civitas came to mean the site of a cathedral.[8] This usage carried over generally to Anglo-Norman cité and English city in England. William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England of 1765[9] cites Edward Coke's Institutes of the Lawes of England of 1634:[10]

A city is a town incorporated, which is or hath been the see of a bishop; and though the bishoprick be dissolved, as at Westminster, yet still it remaineth a city.

Subsequent legal authorities disputed this assertion; pointing out that the City of Westminster gained its status not implicitly from its (former) cathedral but explicitly from letters patent issued by Henry VIII shortly after the Diocese was established.[10]

In any case it was moot whether the association of city with dioceses applied to Ireland. A 1331 writ of Edward III is addressed, among others, to "Civibus civitatis Dublin, —de Droghda, – de Waterford, de Cork, – de Limrik" implying civitas status for Drogheda.[11] Some credence to the episcopal connection was given by the 1835 Report of the Commissioners into Municipal Corporations in Ireland[12][13] and the 1846 Parliamentary Gazetteer of Ireland (see below).

Whereas the Normans moved many English sees from a rural location to a regional hub, the cathedrals of the established Church of Ireland remained at the often rural sites agreed at the twelfth-century Synod of Rathbreasail and Synod of Kells. The Roman Catholic church in Ireland had no cathedrals during the Protestant Ascendancy.

Downpatrick is noted as "the City of Down" in a 1403 record, although no granting instrument is known.[14] The corporation was defunct by 1661, when Charles II initiated plans to revive it, which were not completed.[14]

Although the charter of Clogher did not describe it as a city, the borough constituency in the Irish House of Commons was officially called "City of Clogher".[15] It was a pocket borough of the Bishop of Clogher, disestablished by the Acts of Union 1800.[15]

John Caillard Erck records of Old Leighlin, "So flourishing indeed was this town in subsequent times, that it received the appellation of the city of Leighlin, and was inhabited by eighty-six burgesses during the prelacy of Richard Rocomb, who died in 1420."[16]

Royal charters

For seven settlements in Ireland (listed below), the title "city" was historically conferred by the awarding of a royal charter which used the word "city" in the name of the body corporate charged with governing the settlement. (In fact, charters were for centuries written in Latin, with civitas denoting "city" and villa "town".) Armagh had no charter recognising it as a city but claimed the title by prescription; acts of the Parliament of Ireland in 1773 and 1791 refer to the "city of Armagh".[17] There is one reference in James I's 1609 charter for Wexford to "our said city of Wexford", but the rest of the charter describes it as a town or borough.[18]

The label "city" carried prestige but was purely ceremonial and did not in practice affect the municipal government. However, a few acts of the Parliament of Ireland were stated to apply to "cities". A section of the Newtown Act of 1748[19] allowed for members of a Corporation to be non-resident of its municipality in the case of "any town corporate or borough, not being a city".[20] This was enacted because there were too few Protestants in smaller towns to make up the numbers.[20][21] The 1835 Report of the Commissioners on Municipal Corporations in Ireland questioned whether it was applicable in the case of Armagh and Tuam, both being episcopal sees and hence "cities" in Blackstone's definition. In fact, non-residents had served on both corporations.[12][13] The provisions of a 1785 Act for "the lighting and cleaning of cities" were extended by a 1796 act to "other towns, not being cities".[22] In the 1613 Irish House of Commons, members from a borough constituency were paid 50% more if it was a city.[23]

After the Union

After the Acts of Union 1800, Ireland was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and British law governed the award and removal of the title "city".

The Municipal Corporations (Ireland) Act 1840 abolished both those corporations which were already de facto defunct and those which were most egregiously unrepresentative. The latter category included Armagh and Cashel. It was moot whether these ipso facto were no longer cities; some later sources continued to describe them as such.

The Parliamentary Gazetteer of Ireland

The 1846 Parliamentary Gazetteer of Ireland uses the label "city" in a variety of ways. For Cork,[24] Dublin,[25] Kilkenny,[26] Limerick,[27] Derry,[28] and Waterford,[29] the definition at the start of the relevant article includes "a city". Armagh is defined as "[a] post, market, and ancient town, a royal borough, the capital of a county, and the ecclesiastical metropolis of Ireland"; however it is called a "city" throughout its article.[30] Cashel is treated similarly to Armagh.[31] For other episcopal seats, "city" is not used, or used in hedged descriptions like "episcopal city",[32][33] "ancient city",[32][33][34][35] or "nominal city".[36][37] Of Kilfenora it says, "It belongs to the same category as Emly, Clonfert, Kilmacduagh, Ardfert, Connor, Clogher, Kilmore, Ferns, and Achonry, in exhibiting a shrunk and ghastly caricature upon the practical notion of a 'city;' and nothing but its episcopal name and historical associations prevent it from being regarded as a mean and shabby hamlet."[38] Of Elphin it says "the general tone of at once masonry, manners, and business, is a hideous satire upon the idea of 'a city.'"[39] Of Downpatrick it says "it displays a striking, and almost outré combination of unique and common place character, of ancient piles and modern edifices curiously mingling the features of city and village, of political grandeur and social littleness."[40] There are passing references in other articles to "the city of Tuam",[41] and "the city of Killaloe".[42][43]

Belfast

Belfast in 1887 applied to be granted city status on the occasion of Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee.[44] The Home Office objected to setting a precedent for granting city status to towns not episcopal sees.[45] Thomas Sexton asked in the House of Commons:[46]

with regard to the granting of the City Charter to Belfast. A Question was lately put in the House upon the subject, and ... [ W. H. Smith] replied ... that the Government did not intend to recommend any such grant in connection with Her Majesty's Jubilee. ... I will ask him for a reply upon the point ... I do not know that there is much difference between a town and a city; but some people prefer the title of city, and if there is any advantage in a place being called a city, I think the people of Belfast are entitled to have their choice. There are eight cities in Ireland, and Belfast is next to Dublin in point of importance; according to Thom's information, it is the first town of manufacturing importance. I believe there is a strong desire that the title of city should be given to the place. ... It seems absurd that Belfast should be shut out from any City Charter, while Armagh, with 10,000 of a population, is a city; and when Cashell, with a population of 4,000, enjoys the distinction also. Perhaps the right hon. Gentleman the Chancellor of the Exchequer will be able to say that, in consideration of the importance of the town, the Government will recommend the Crown to grant to it the title of city. Like civility, a Charter of this kind costs nothing; and, therefore, I think that this Charter might be promptly and gracefully conceded to the town.

In 1888, the request was granted by letters patent, setting a precedent for non-episcopal cities which was soon emulated by Dundee and Birmingham.[47]

County corporate and county borough

Prior to the Local Government (Ireland) Act 1898, eight Irish municipalities were counties corporate. This was distinct from being a city. Five of the counties corporate were "County of the City", the other three being "County of the Town". The other cities —Derry, and until 1840 Cashel and Armagh— were not governed separately from their surrounding counties; however, the official name of County Londonderry was for long "the City and County of Londonderry". The 1898 act abolished the corporate counties of the city of Kilkenny and the towns of Galway, Drogheda, and Carrickfergus, and converted the other four corporate counties into county boroughs, a new class which also included the cities of Derry and Belfast.

"Lord Mayor" and "Right Honourable"

The title lord mayor is given to the mayor of a privileged subset of UK cities. In some cases, a lord mayor additionally has the style "Right Honourable". The Mayor of Dublin gained the title "lord" by a charter of 1641,[48][49] but the Confederate Wars and their aftermath meant the form "lord mayor" was not used until 1665.[49] The style "Right Honourable" was originally a consequence of the lord mayor's ex officio membership of the Privy Council of Ireland; it was later explicitly granted by the 1840 Act. The Lord Mayor of Belfast gained the title in 1892 —based on the precedent of Dundee[50]— and the style "Right Honourable" in 1923, in recognition of Belfast's status as capital of the newly created Northern Ireland. The Lord Mayor of Cork gained the title in 1900, to mark Queen Victoria's visit to Ireland;[51] the style "Right Honourable" has never applied. Armagh gained a lord mayor in 2012 for the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II.[52] The title of Right Honourable in the cities of Cork and Dublin was abolished by the Local Government Act 2001.[53]

Northern Ireland

Armagh

In the area which in 1921 became Northern Ireland, after Belfast received its charter in 1888, no further towns applied for city status until 1953, when Armagh began to argue for the restoration of the status lost in 1840.[54] Its justification was that the Archbishop of Armagh was Primate of All Ireland. The council used the appellation "city" unofficially; when Milford Everton F.C. moved from Milford to Armagh in 1988 it took the name Armagh City F.C. In 1994, Charles, Prince of Wales announced that city status had been granted to mark the 1,550th anniversary of the traditional date of Armagh's foundation by Saint Patrick.[55]

Lisburn and Newry

Lisburn and Ballymena entered a UK-wide competition for city status held to mark the millennium in 2000; neither was selected, being below the unofficial 200,000 population threshold.[56] Controversy surrounded the decision-making process for the competition, and as a result the rules changed for a 2002 competition for the Golden Jubilee of Elizabeth II, with Northern Ireland guaranteed one new city.[57] This encouraged more applicants, with Lisburn and Ballymena being joined by Carrickfergus, Craigavon, Coleraine, and Newry.[58] Surprisingly, Lisburn and Newry were both successful, prompting allegations of political expediency, since Lisburn is strongly Protestant and Newry strongly Catholic.[59] Ballymena representatives were aggrieved, and there were claims that Lisburn, as a suburb of Belfast, ought to be ineligible.[60] Sinn Féin members of Newry and Mourne District Council were opposed to Newry's city status because of the connection to the British monarchy; other councillors welcomed the award.[61] In 2004 Newry Town F.C. renamed to Newry City F.C. Despite the failure of Craigavon's bid, Craigavon City F.C. has used City in its name since its 2007 foundation.

Bangor

Coleraine and Craigavon were again among the 26 applicants for city status at the 2012 Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II,[62] but neither was among the three successful.[52] Ballymena, Bangor, and Coleraine were among the 39 towns applying for city status as part of the Platinum Jubilee Civic Honours,[63] with Bangor among the eight winners announced on 20 May 2022.[64] A Bangor Green Party member of Ards and North Down Borough Council suggested the £10,000 to update Bangor's four welcome signs should not be spent during the UK cost-of-living crisis.[65] The production by the Crown Office of the letters patent formally granting city status was delayed by the death of Elizabeth II.[66] The revised document was issued on 22 November by the Clerk of the Crown for Northern Ireland under the royal sign manual of the new king, Charles III.[67] It was formally presented at Bangor Castle on 2 December by Anne, Princess Royal to the Vice Lord Lieutenant of County Down, Catherine Champion, and the Mayor of Ards and North Down, Karen Douglas.[67][68]

Current list

Thus the recognised cities in Northern Ireland as of 16 November 2022 number five (Armagh, Belfast, Derry, Lisburn, Newry)[69][70] plus one announced for later in 2022 (Bangor).[71] The local government districts named after two of the new cities were granted a corresponding change of name: from "Armagh District" to "Armagh City and District",[72] and from "Lisburn Borough" to "Lisburn City".[73] just as the older cities had Belfast City Council and Derry City Council. Newry and Mourne district's name did not use the word "city". In 2014–2015, the number of districts was reduced from 26 to 11 by merging all except Belfast with neighbouring ones. The successor districts inherited city status where applicable: those linked to a charter (Belfast, Derry, Lisburn) by request of its council, and those not linked to a charter (Armagh, Newry) automatically.[70][74] This is reflected in the names of Derry City and Strabane District Council, Lisburn and Castlereagh City Council and Armagh City, Banbridge and Craigavon Borough Council, but not in that of Newry, Mourne and Down District Council.

Republic of Ireland

On the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922 (Ireland from 1937), there were four county boroughs within its jurisdiction: Dublin, Cork, Limerick and Waterford. Galway was made a fifth county borough in 1986.[75] The Local Government Act 2001 redesignated the five county boroughs as cities.[76] These cities, like the county boroughs before them, are almost identical in power and function to the administrative counties. The five administrative cities were Cork, Dublin, Galway, Limerick, and Waterford.[77] The Local Government Reform Act 2014 amalgamated the cities of Limerick and Waterford with their respective counties, creating local government areas under the category of Cities and Counties.[78]

Dublin

The Constitution of Ireland adopted in 1937 prescribes that the Oireachtas must meet, and the President must reside, "in or near the City of Dublin"; the only occurrences of "city" in the Constitution.[79] In fact Leinster House and Áras an Uachtaráin are within the municipal limits of the city. The formula "in or near the City of Dublin" had occurred in earlier statutes, including Ormonde's Articles of Peace of 1649[80] and the 1922 Constitution.[81]

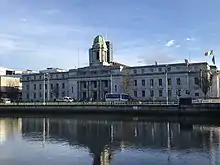

Cork

A 2015 review proposed a merger of Cork city and county by 2019, but was not implemented after objections from the city.[82][83] Instead, the boundary of the city of Cork was extended.

Limerick and Waterford

The Local Government Reform Act 2014 amalgamated the local government areas of the county of Limerick and the city of Limerick to form a single local government area named as Limerick City and County, and amalgamated the local government areas of the county of Waterford and the city of Waterford to form a single local government area named as Waterford City and County, with the first elections held to the new Limerick City and County Council and Waterford City and County Council at the 2014 local elections.[84][85] Each of the two merged local government areas is termed a "city and county".[86] The changes are "without prejudice to the continued use of the description city in relation to Limerick and to Waterford".[87] Within each "city and county", the municipal district which contains the city is styled a "metropolitan district" (Ceantar Cathrach in Irish).[88]

Waterford, Ireland's oldest city is believed to have been established by the Viking Ragnall (the grandson of Ivar the Boneless) in 914 AD.

Galway

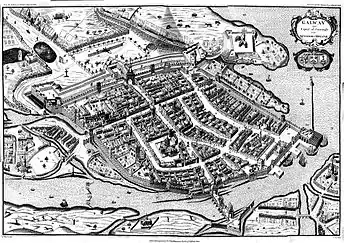

Galway's status as a city was for long debatable.[89] Its nickname was "the city of the Tribes" due to the fact that there were 14 main tribes there Athy, Blake, Bodkin, Browne, Darcy, Deane, French, Font, Joyce, Kirwan, Lynch, Martin, Morris, and Skerrett, families, but in British times it was legally a town, and its county corporate was the "county of the town of Galway".[90] Its 1484 charter grants its corporation's head the title of Mayor,[91] but so did the charters of Clonmel and Drogheda,[92] as well as the charters extinguished in 1840 of Carrickfergus, Coleraine, Wexford, and Youghal,[93] none of which claimed the title of "city". Under Irish self Rule however, there has never been any debate about the city's status

Galway was nevertheless intermittently described as a city; John Speed's 1610 map of "Connaugh" includes a plan of "the Citie of Galway".[94] In The history of the town and county of the town of Galway (1820), James Hardiman generally describes it as a town. However, his account of the 1651 map commissioned by Clanricarde concludes that at the time Galway "was universally acknowledged to be the most perfect city in the kingdom".[95] Robert Wilson Lynd in 1912 referred to "Galway city – technically, it is only Galway town —".[96] The Local Government (Galway) Act 1937, describes it as the "Town of Galway" and created a municipal government called the "Borough of Galway".[97] On the other hand, the Aran Islands (Transport) Act 1936, regulates steamships travelling "between the City of Galway and the Aran Islands";[98] and legislators debating the passage of the 1937 Act frequently referred to Galway as a "city".[99][100]

In 1986, the Borough of Galway became the County Borough of Galway and ceased to part of County Galway.[75][101] The Borough Council became the "City Council" and it acquired its own "City Manager".[75] This was not presented as the acquiring of city status; Minister for the Environment Liam Kavanagh said it was "the extension of the Galway City boundary and for upgrading of that city to the status of county borough".[102]

Galway only officially became a city in 2001 under the Local Government Act of that year.[103]

A proposal to merge Galway city and county was put on hold in 2018 after Seanad opposition, and has now been completely abandoned by the government.[104]

Kilkenny

The only city in the Republic which was not a county borough was Kilkenny. The Local Government Bill 2000, as initiated, would have reclassified as "towns" all "boroughs" which were not county boroughs, including Kilkenny.[105] This drew objections from Kilkenny's borough councillors, and from TDs Phil Hogan and John McGuinness.[106] Accordingly, a clause was added to the bill:[107]

This section is without prejudice to the continued use of the description city in relation to Kilkenny, to the extent that that description was used before the establishment day and is not otherwise inconsistent with this Act.

The Act also states:[108]

Subject to this Act, royal charters and letters patent relating to local authorities shall continue to apply for ceremonial and related purposes in accordance with local civic tradition but shall otherwise cease to have effect.

Minister of State Tom Kitt explained these provisions as follows:[109]

New provisions to recognise the term "city" to describe Kilkenny in line with long-established historical and municipal practice were brought in. Kilkenny was reconstituted as a borough corporation under the Municipal Corporations Act, 1840, as were Clonmel, Drogheda and Sligo. Section 2 of the 1840 Act specifically provided that Kilkenny is a borough which is still the current legal position in local government law. Traditionally, however, Kilkenny had been referred to as a city and this has its roots in local usage, deriving from a 17th-century charter. It has not been a city in terms of local government law for at least 160 years.

As I have indicated, the Bill as published specifically provides that local charters can continue for ceremonial or related purposes, thereby safeguarding local tradition and practice. There was, therefore, no difficulty in Kilkenny continuing with this long-established tradition. However, Kilkenny Corporation indicated that it was concerned that the existing provisions in the Bill would not maintain the status quo in addition to concerns with the other boroughs that the term "town" was some form of diminution of status. In view of these concerns, the Minister [ Noel Dempsey ] indicated that he would include a provision in the Bill to specifically recognise the traditional usage of the term "city" to describe Kilkenny. For the first time ever in the Local Government Act, the unique position of Kilkenny is being recognised in local government law.

The Minister honoured in full his commitment on Kilkenny and delivered on what the deputation from Kilkenny sought. It was never intended that Kilkenny would be a city such as Dublin or Cork. All Kilkenny wanted was to be allowed to continue to use the term "city" in recognition of its ancient tradition. The deputation expressed its satisfaction to the Minister on his proposal.

In 2002, Phil Hogan (a Fine Gael TD) asked for "full city status" for Kilkenny;[110] in 2009 he said "Kilkenny has lost its City status courtesy of Fianna Fáil".[111]

The Local Government Reform Act 2014, which had been proposed by Phil Hogan as Minister for the Environment, Community and Local Government, dissolved all boroughs and towns, including Kilkenny, and established municipal districts in all counties outside Dublin. Whereas the municipal district encompassing other boroughs are styled "the Borough District of Sligo [or Drogheda/Wexford/Clonmel]", that encompassing Kilkenny is styled "the Municipal District of Kilkenny City".[112]

National Spatial Strategy

The National Spatial Strategy (NSS) for 2002–2020 planned to manage urban sprawl by identifying certain urban centres outside Dublin as areas for concentrated growth. The NSS report calls the regional centres "gateways" and the sub-regional centres "hubs".[113] It does not call them "cities", but among the features it lists for "Gateways" are "City level range of theatres, arts and sports centres and public spaces/parks." and "City-scale water and waste management services."[114] It also gives a target population for a gateway of over 100,000, including the suburban hinterland.[114]

The report describes Cork, Limerick/Shannon, Galway and Waterford, as "existing gateways" and identifies four "new national level gateways": Dundalk, Sligo, and two "linked" gateways Letterkenny/(Derry), and Athlone/Tullamore/Mullingar.[113] The campaigns of Sligo and Dundalk for city status have referenced their status as regional gateways. The "Midlands Gateway", a polycentric zone based on Tullamore, Athlone, and Mullingar, has occasionally been described as constituting a new or future city.[115][116] A 2008 study by Dublin Institute of Technology concluded that the growth in population of the designated gateways was far less than had been planned.[117]

Proposed cities

Local councillors and TDs from several towns have raised the possibility of gaining city status. Prior to the 2001 Act, these suggestions were a matter of simple prestige. Since the 2001 Act, the suggestions sometimes relate to the administrative functions of county-equivalent cities and sometimes to the ceremonial title. The Minister for Housing, Local Government and Heritage has not entertained these suggestions,[118][119] and has said "A modernised legal framework and structures at both regional and local level are now in place ... I have no proposals for amending legislation, which would be necessary to establish new city councils."[120]

Drogheda

The possibility of Drogheda gaining city status was raised in Dáil questions by Gay Mitchell in 2005,[121] Michael Noonan in 2007[120] and by Fergus O'Dowd in 2007[118] and 2010.[122] The Borough Council's draft development plan for 2011–17 does not mention city status,[123] although the manager's summary of public submissions reported backing for city status for the greater Drogheda area, incorporating adjacent areas in Counties Louth and Meath.[124] In 2010, a "Drogheda City Status Campaign" was launched,[125] and in March 2012, Drogheda Borough Council passed a resolution, "That the members of Drogheda Borough Council from this day forward give their consent and approval to the people of Drogheda referring to Drogheda as the City of Drogheda".[126][127]

Dún Laoghaire

A 1991 official report recommended that the borough of Dún Laoghaire should be "upgraded to city [i.e. county borough] status" with an extended boundary;[128] instead the Local Government (Dublin) Act 1993 used a similar boundary to delimit a new administrative county, subsuming the old borough, named Dún Laoghaire–Rathdown.[129]

Dundalk

Dundalk's development plan for 2003–09 stated "Dundalk, in order to fulfil its potential as a regional growth centre, should, in the near future achieve City Status, to acknowledge its present role and to enable its future growth as a regional gateway."[130] Michael Noonan asked a question in the Dáil in 2007.[120] Dundalk's draft development plan for 2009–15 seeks to develop the "Newry–Dundalk Twin City Region" with Newry, which is nearby across the border.[131] The county manager of County Louth made a summary of public submissions on the plan, which predicted Dundalk Institute of Technology being upgraded to university status would help to win city status.[132]

Sligo

John Perry raised an adjournment debate in 1999 calling for Sligo to be declared a "millennium city", stating:[133]

While the Government will probably say Sligo can call itself a city, an official declaration by the Government to declare Sligo the millennium city will confer an official status on it. The word 'city' has a certain meaning for investors. ... The requirement for a town to be called a city is that it be a seat of government or a cathedral town. Sligo is sometimes called a town and sometimes a city. This leads to confusion and the region falls between both stools. An official declaration of Sligo as a millennium city would have major significance for the entire area. The word city has a certain meaning for investors. It presumes a certain level of services and a status towards which the world reacts very favourably. The Fitzpatrick report established Sligo as a future growth centre. Even officials of Sligo Corporation are confused because in certain instances Sligo is called a town and in others a city.

Declan Bree, mayor of the town in 2005, advocated "Sligo gaining city status similar to Limerick, Galway and Waterford."[134] The town council and county council held meetings to plan an expansion of the borough boundaries with a view to enhancing the prospects for such a change.[134]

The main building of Sligo Borough Council is called "City Hall".[135] However Sligo is still not officially recognised as a City

Swords

Michael Kennedy, TD for Dublin North, stated in 2007 that "Fingal County Council is planning to confer city status on our county town of Swords in the next 15 to 20 years as its population grows to 100,000."[136] In May 2008, the Council published "Your Swords, an Emerging City, Strategic Vision 2035", with a vision of Swords as "an emerging green city of 100,000 people."[137]

Tallaght

A campaign to have Tallaght given city status was launched in 2003 by Eamonn Maloney, a member of South Dublin County Council.[138] It is supported by the Tallaght Area Committee, comprising 10 of the 26 county councillors.[138] Advantages envisaged by the campaign's website include having a dedicated Industrial Development Authority branch office for attracting investment, and facilitating the upgrade of Institute of Technology, Tallaght to university status.[139] When Charlie O'Connor asked about city status for "Tallaght, Dublin 24" in 2007, the minister had "no plans to re-designate South Dublin County Council as a city council, or to establish Tallaght as a separate city authority".[119] O'Connor said later "The only problem I can see is our close proximity to Dublin".[138] The head of the local chamber of commerce said in 2010, "If Tallaght was anywhere else in the country, it would have been a city years ago. We already have the population, the hospital and the third-level institution. If we're missing something, someone needs to tell us, clarify what the criteria [are], and we'll get it."[138]

List

This list includes places which have at some time had a legally recognised claim to the title "city". Informally the term may have been applied to other places or at other times.

Current

Cities in Northern Ireland are denoted by a light blue background.

Former

| Name | Gained status |

Method of granting | Jurisdiction granting | Lost status | Present jurisdiction |

Province |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Armagh (1st time) | By 1226[55] | prescription[55] | Lordship of Ireland | 1840[t 2] | Northern Ireland | Ulster |

| Downpatrick ("Down")[14] | By 1403[14] | Lordship of Ireland | By 1661[14] | Northern Ireland | Ulster | |

| Clogher[15] | Lordship of Ireland | 1801[15] | Northern Ireland | Ulster | ||

| Cashel | 1638[146] | royal charter[146] | Kingdom of Ireland | 1840[t 2] | Republic of Ireland | Munster |

- Officially Londonderry. See Derry/Londonderry name dispute

- The 1871 census' summary report includes "Armagh City" and "Cashel City" among the subdivisions.[145]

See also

References

Citations

- "city". Focal. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- "town". Focal. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- "baile". Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language. Royal Irish Academy. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- "cathair". Electronic Dictionary of the Irish Language. Royal Irish Academy. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- "Dublin, the history of the placename" (PDF) (in Irish and English). The Placenames Branch. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 June 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

The element baile, 'town', was prefixed to the name some time in the 15th century

- 1835 Rep Comm Mun Corp Irl Vol 9 Pt 1 p.2

- Ó Cearúil, Micheál; Ó Murchú, Máirtín (1999). Bunreacht na hÉireann: A study of the Irish text (PDF). for the All-Party Oireachtas Committee on the Constitution. Dublin: Stationery Office. pp. 172–3, 225–6. ISBN 0-7076-6400-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Galinié, Henri (2000). "Civitas, City". In Vauchez, André; Dobson, Richard Barrie; Lapidge, Michael (eds.). Encyclopedia of the Middle Ages. Routledge. p. 313. ISBN 978-1-57958-282-1. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- Blackstone, William (1765). "Introduction §4: Of the Countries subject to the Laws of England". Commentaries on the Laws of England. Vol. 1. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 111. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

- Coke, Edward; Hale, Matthew; Nottingham, Heneage Finch, Earl of; Francis Hargrave, Charles Butler (1853). "109b". A commentary upon Littleton. The Institutes of the laws of England. Vol. 1 (1st American, from 19th London ed.). Philadelphia: R. H. Small. Vol. 1 pp.163–5. Retrieved 17 May 2010.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gale 1834, Appendix 35; Writ of King Edward the Third, issued in the year 1331, to the prelates and peers, and cities of Ireland, to assist his Justiciary, p.cclii

- 1835 Rep Comm Mun Corp Irl p.671–2 "City of Armagh" §10

- 1835 Rep Comm Mun Corp Irl p.432 "Borough of Tuam" §13

- 1835 Rep Comm Mun Corp Irl p.797

- 1835 Rep Comm Mun Corp Irl pp.997–998

- Erck, John Caillard (1827). The ecclesiastical register: containing the names of the dignitaries and parochial clergy of Ireland : as also of the parishes and their respective patrons and an account of monies granted for building churches and glebe-houses with ecclesiastical annals annexed to each diocese and appendixes : containing among other things several cases of quare impedit. R. Milliken and Son. p. 128. Retrieved 14 May 2010.

- 13 & 14 George III c.40 and 31 George III c.46

- Gale 1834, Appendix 17: Translation from enrolment in Chancery of the charter to the town of Wexford by James the First; pp.lxxxiii–lxxxiv

- 21 Geo. 2 c. 10 (Ir) s. 8

- Rept Comm Mun Corp Irl pp.19–20

- Malcomson, A. P. W. (March 1973). "The Newtown Act of 1748: Revision and Reconstruction". Irish Historical Studies. Irish Historical Studies Publications. 18 (71): 313–344. doi:10.1017/S0021121400025840. JSTOR 30005420. S2CID 159997457.

- [1785] 25 Geo.3 c.54 s.3 and [1796] 36 Geo.3 c.51 s.1; see also preamble of [1828] 9 Geo.4 c.82

- Steele, Robert (1910). "The Council of Ireland and its Proclamations". Bibliography of royal proclamations of the Tudor and Stuart sovereigns and of others published under authority, 1485–1714; Vol. I. Bibliotheca Lindesiana. Vol. V. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. cxxviii. Retrieved 16 February 2021 – via National Library of Scotland.

in 1613 the wages paid by the constituencies were, to knights of the shire, 13s. 4d.; citizens, 10s.; burgesses, 6s. 8d. per day.

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.1 p.519 "Cork" "A sea-port, a parliamentary borough, a city, the assize-town of the county of Cork, the capital of Munster, and the second town of Ireland"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.2 p.108 "Dublin" "The metropolis of Ireland, the second city of the British empire, and the seventh city of Europe"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.2 p.431 "Kilkenny" "A post and market town, a municipal and parliamentary borough, a city, the capital of the county of Kilkenny, and the seat of the diocese of Ossory"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.2 p.632 "Limerick" "A post, market, and sea-port town and borough, a city, and the capital of Western Munster"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.2 p.672 "Londonderry" "A post, market, and sea-port town, a borough, a city, the county town of Londonderry, and the capital of the extreme north of Ulster"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.3 p.488 "Waterford" "A post and market town, a sea-port, a borough, a city, and the capital of the county of Waterford"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.1 p.78 "Armagh"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.1 p.342 "Cashel" "A post and market town, a borough, an episcopal city, and the ecclesiastical metropolis of the southern province of Ireland"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.1 p.418 "Clogher" "An ancient episcopal city and incorporated town, but at present a mere village"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.1 p.470 "Cloyne" "A market and post town, and an ancient Episcopal city"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.1 p.56 "Ardfert" "This ancient and once important city is now a poor and declining village"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.2 p.176 "Emly" "Though now a mere village, it is noticed by some ancient historians as in their day a large and flourishing city."

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.1 p.493 "Connor" "the farce of nominal city character"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.2 p.77 "Dromore" "Though nominally a city, it is really but a small and common-place market-town."

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.2 p.409

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.2 p.174

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.2 p.60

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.3 p.398 "Tuam" [parish] "The Clare and the Dunmore sections contain the city of Tuam"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.2 p.552 "Kincora" "1 mile north-northwest of the city of Killaloe"

- 1846 Parl Gaz Irl Vol.3 p.251 "Slieve Bernagh" "it soars gradually up in the western vicinity of the city of Killaloe"

- Beckett 2005, p.44

- Beckett 2005, p.45

- "Civil Services". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). Vol. 317. HC. 15 July 1887. col. 977–978.

- Beckett 2005, pp. 45–50.

- 1835 Rep Comm Mun Corp Irl Vol 9 Pt 1 p.5

- "History of the Lord Mayor's Office". Dublin City Council. Archived from the original on 19 April 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Beckett 2005 p.67

- Beckett 2005 p.68

- "Three towns win city status for Diamond Jubilee". BBC Online. 14 March 2012. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- Local Government Act 2001 §32(3)b

- Beckett 2005, p.133

- Beckett 2005, p.134

- Beckett 2005, pp. 141–163.

- Beckett 2005,p.153

- Beckett 2005, p. 170.

- Beckett 2005, p. 174.

- Beckett 2005, p.175

- "D.D.84./2002 – CITY STATUS" (PDF). Minutes of District Development Committee Meeting. Newry and Mourne District Council. 19 March 2002. pp. 4–7. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "More than 25 towns bid for Diamond Jubilee city status". BBC News. 16 June 2011. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- "City status: The 39 towns competing for an upgrade revealed". BBC News. 23 December 2021. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- "Platinum Jubilee: Eight towns to be made cities for Platinum Jubilee". BBC News. 19 May 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- Kenwood, Michael (15 November 2022). "Questions raised over cost of new Bangor 'City' signs". BelfastLive. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- "Yuletide Joy for the City of Bangor". County Down Spectator. 10 November 2022. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- "Bangor receives city status in Princess Anne visit". BBC News. 2 December 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

-

- McCambridge, Jonathan (3 December 2022). "The Princess Royal gives official seal of approval for new city Bangor". PA. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- "Court Circular". The Times. London. 2 December 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- Beckett 2005, p.185

- DOENI (Department of the Environment (Northern Ireland)) (20 October 2014). "Draft Local Government (Transitional, Incidental, Consequential and Supplemental Provisions) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2014: Charters and Status: Consultation Document" (PDF). p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 April 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Leadbeater, Chris (27 May 2022). "Ranked and rated: Which of the new Jubilee cities really deserves the title?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

Bangor becomes Northern Ireland's sixth city – following the examples of Belfast, Armagh, Londonderry, Lisburn and Newry

- "Change of District Name (Armagh) Order (Northern Ireland) 1995". Belfast Gazette (5656): 804. 15 September 1995. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "Change of District Name (Lisburn Borough) Order (Northern Ireland) 2002". Office of Public Sector Information. 5 July 2002. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- "The Local Government (Transitional, Incidental, Consequential and Supplemental Provisions) Regulations (Northern Ireland) 2015". Legislation.gov.uk. 5 March 2015. Retrieved 12 May 2017.

- Local Government (Reorganisation) Act 1985, s. 5: Establishment of Borough of Galway as County Borough (No. 7 of 1985, s. 5). Enacted on 3 April 1985. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 24 June 2021.

- Local Government Act 2001, s. 10: Local government areas (No. 37 of 2001, s. 10). Enacted on 21 July 2001. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 24 June 2021.

- Local Government Act, 2001; Schedule 5, Part 2

- Local Government Reform Act 2014, s. 12: Local government areas (No. 1 of 2014, s. 12). Enacted on 27 January 2014. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 27 December 2021.

- Art 12.11.1°, Art 15.1.3° "Constitution of Ireland". Irish Statute Book. Attorney General of Ireland. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- Historical Collections of Private Passages of State, Weighty Matters in Law Part 4 Vol 1 p.415 John Rushworth, London, 1701

- Constitution of the Irish Free State (Saorstát Eireann) Act, 1922 Irish Statute Book

- Cork Local Government Committee (September 2015). "Local Government Arrangements in Cork" (PDF). Department of the Environment, Community and Local Government. pp. 9–10. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- English, Eoin (30 June 2016). "Review of controversial merger plan for Cork city and county councils". Irish Examiner. Retrieved 6 February 2017.; "Local Government Bill 2018: Second Stage". Dáil Éireann debate. Oireachtas. 18 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Local Government Reform Act 2014, s. 9: Cesser and amalgamation of certain local government areas (No. 1 of 2014, s. 9). Enacted on 27 January 2014. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 27 December 2021.

- Local Government Reform Act 2014: * sec.12(1) [amending sec.10(2) of the Local Government Act 2001] * sec.12(2) [adding Part 3 to Schedule 5 of the Local Government Act 2001]

- Local Government Reform Act 2014, sec 9(1)(a)(ii) and 9(1)(c)(ii)

- Local Government Reform Act 2014, sec.12(1) [amending sec.10(6)(b) of the Local Government Act 2001]

- Local Government Reform Act 2014, sec.19 [insertion into Local Government Act 2001 of Section 22A(2)(a)]

- Beckett 2005, p.16

- Parl Gazz Irl 1846 Vol.2 p.237

- "History of The City Council". Galway City Council. Archived from the original on 13 December 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Municipal Corporations (Ireland) Act 1840, Schedule A

- Municipal Corporations (Ireland) Act 1840, Schedule B

- Abbott, T. K. (1900). "Maps, Plans, etc., principally relating to Ireland (some printed).". Catalogue of the manuscripts in the Library of Trinity College, Dublin, to which is added a list of the Fagel collection of maps in the same library. Dublin: Hodges Figgis. pp. 238, No.70.

- Hardiman, James (1820). The history of the town and county of the town of Galway. Dublin. p. 29. Retrieved 16 May 2010.

- Lynd, Robert (1912). Rambles in Ireland. D. Estes & company. p. 14.

- Local Government (Galway) Act 1937, s. 4: Formation of the Borough of Galway (No. 3P of 1937, s. 4). Enacted on 10 June 1937. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 24 June 2021.

- Aran Islands (Transport) Act 1936, s. 2: Contracts for steamer service to the Aran Islands (No. 36 of 1936, s. 2). Enacted on 24 July 1936. Act of the Oireachtas. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 24 June 2021.

- Oireachtas, Houses of the (11 July 1934). "Seanad Éireann debate - Wednesday, 11 Jul 1934". www.oireachtas.ie.

- "Private Business. - Local Government (Galway) Bill, 1937—Fifth Stage – Dáil Éireann debate". Houses of the Oireachtas. 9 June 1937.

- Local Government (Reorganisation) Act 1985 (County Borough of Galway) (Appointed Day) Order 1985 (S.I. No. 425 of 1985). Signed on 18 December 1985. Statutory Instrument of the Government of Ireland. Retrieved from Irish Statute Book on 24 June 2021.

- Local Government (Reorganisation) Bill, 1985: Second Stage. Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dáil Éireann – Volume 356 – 14 March 1985

- Section 10 and Schedule 5 of the Local Government Act, 2001.

- "No.101: Local Authority Boundaries". Parliamentary Questions (33rd Dáil). Oireachtas. 28 January 2021. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- "Local Government Bill, 2000 (as initiated)" (PDF). Oireachtas. 4 May 2000.

- Local Government Bill, 2000: Second Stage (Resumed). Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dáil Éireann – Volume 538 – 13 June 2001

- Local Government Act, 2001 §10(7)

- Local Government Act, 2001 §11(16)

- Local Government Bill, 2000: Committee Stage. Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Seanad Éireann – Volume 167 – 11 July 2001

- Written Answers. – City Status. Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dáil Éireann – Volume 550 – 20 March 2002

- Keane, Sean (24 July 2009). "Jobs, funding under threat as Bord Snip gets set to slash". Kilkenny People. Archived from the original on 29 July 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Local Government Reform Act 2014, sec. 19 [insertion into Local Government Act 2001 of Section 22A(2)(b) and 22A(2)(c)]

- NSS 2002, p.38

- NSS 2002, p.40

- "New Athlone retail complex to tap into Midlands' new wealth". Irish Independent. Dublin. 22 June 2005. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

the government's National Spatial Strategy [creates] a major city by linking the towns of Athlone, Mullingar and Tullamore.

- "Calls for re-opening of railway line". RTÉ.ie. RTÉ. 15 April 2005. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

Delegates were also told that the gateway towns of Athlone, Tullamore and Mullingar would constitute a joint city with a population of over 100,000 people within the next 30 years.

- "Sligo won't ever be a city, says Dublin-based report". Sligo Weekender. 5 February 2005. Archived from the original on 22 June 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- Written Answers. – City Status. Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dáil Éireann – Volume 636 – 24 April 2007

- Written Answers. – Local Government Reform. Dáil Éireann – Volume 638 – 26 September 2007

- Written Answers. – City Status. Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dáil Éireann – Volume 635 – 5 April 2007

- Oireachtas, Houses of the (28 June 2005). "Dáil Éireann debate - Tuesday, 28 Jun 2005". www.oireachtas.ie.

- Oireachtas, Houses of the (11 May 2010). "Dáil Éireann debate - Tuesday, 11 May 2010". www.oireachtas.ie.

- "Draft Drogheda Borough Council Development Plan 2011–2017". Drogheda Borough Council. 2009. Archived from the original on 30 April 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- Murray, Conn (1 September 2009). "Theme 1 : Development Strategy." (PDF). Drogheda Borough Council Review of Development Plan 2005–2011: Managers Report prepared under Section 11 (4) of the Planning and Development Act 2000 in relation to submissions received. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2011.

- Murphy, Hubert (20 October 2010). "Drogheda now regarded as major city in all but name". Drogheda Independent. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- "51/12 Notice of Motion – The Mayor, Councillor K. Callan". Minutes of Council Meeting of Drogheda Borough Council held in the Governor's House, Millmount, Drogheda, on 5th March, 2012, at 7.00 p.m. Archived from the original (MS Word) on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- "Drogheda City Status group to meet with Minister Hogan". Drogheda Independent. 11 April 2012. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Advisory Expert Committee (1991). Local government reorganisation and reform (PDF). Vol. Pl.7918. Dublin: Stationery Office. p. 3. ISBN 0-7076-0156-8. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Local Government (Dublin) Act 1993 s.15(2)". electronic Irish Statute Book (eISB). Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "1 Introduction & Context" (PDF). Dundalk & Environs Development Plan. Dundalk Town Council. p. 8. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- "3.2.3 Economic Corridor" (PDF). Dundalk And Environs Development Plan 2009–2015. Dundalk Town Council. 2009. p. 32. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2011. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Managers Report prepared under Section 11 (4) of the Planning and Development Act 2000 in relation to submissions received (PDF). Dundalk Town Council. August 2008. pp. 7 Theme 1 : Economic Strategy b) Achieving City Status. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 August 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Adjournment Debate. – City Status for Sligo. Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dáil Éireann – Volume 510 – 9 November 1999

- Bree, Declan (28 June 2005). "Sligo seeks to push out towards city status". Sligo Weekender. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "The Story of the City Hall". Sligo Borough Council. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- Local Government (Roads Functions) Bill 2007: Second Stage (Resumed). Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dáil Éireann – Volume 641 – 14 November 2007

- "Your Swords, an Emerging City, Strategic Vision 2035" (PDF). Fingal County Council. May 2008. p. 1. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- McInerney, Sarah (14 March 2010). "Tallaght relaunches fight for city status". The Sunday Times. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- "About The Campaign". Tallaght City Campaign. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2010.

- Charters Archived 4 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine Cork City Council

- Patrick Fitzgerald, John James McGregor; The history, topography and antiquities, of the county and city of Limerick Vol 2 App p.iii

- Charles Smith, The ancient and present state of the county and city of Waterford p.106

- 1835 Rep Comm Mun Corp Irl p.534

- City commemorates the 400th Anniversary of the City’s first charter as illustrated by the Life and Times of Sir Henry Docwra Archived 2 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine Derry City Council 2004

- "Table I. The number of inhabitants in each province, county, city, and certain corporate towns, in 1841, 1851, 1861, and 1871; with the approximate increase or decrease between 1861 and 1871". Census of Ireland, 1871; Abstract of the enumerators' returns. Command papers. Vol. LIX. Dublin: Alexander Thom for HMSO. 1871 [C.375]. p. 7. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- 1835 Rep Comm Mun Corp Irl p.462

Sources

- Beckett, John V. (2005). City status in the British Isles, 1830–2002. Historical Urban Studies. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 0-7546-5067-7 – via Internet Archive.

- Gale, Peter (1834). An inquiry into the ancient corporate system of Ireland. Bentley. Retrieved 15 May 2010.

- Reports of Commissioners on the state of the municipal corporations in Ireland; Parliamentary papers: 1835, Vols. XXVII–XXVIII; 1836, Vol. XXIV.

- The Parliamentary Gazetteer of Ireland adapted to the new Poor-Law, Franchise, Municipal and Ecclesiastical arrangements ... as existing in 1844–45. Dublin: A. Fullarton & Co. 1846. Vol. I: A–C, Vol. II: D–M, Vol. III: N–Z

- "Local Government Act, 2001". Irish Statute Book. Attorney General of Ireland. Retrieved 13 May 2010.

- "Local Government Reform Act 2014". Irish Statute Book. 15 October 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- National Spatial Strategy for Ireland 2002 – 2020 (PDF). Dublin: The Stationery Office. 2002.