Citrus psorosis ophiovirus

Citrus psorosis ophiovirus is a plant pathogenic virus infecting citrus plants worldwide.[2] It is considered the most serious and detrimental virus pathogen of these trees.

| Citrus psorosis ophiovirus | |

|---|---|

| |

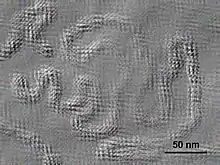

| Electron micrograph of Citrus psorosis ophiovirus | |

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Milneviricetes |

| Order: | Serpentovirales |

| Family: | Aspiviridae |

| Genus: | Ophiovirus |

| Species: | Citrus psorosis ophiovirus |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Citrus psorosis virus | |

Psorosis disease

Psorosis includes various graft-transmitted diseases all of which can be associated with different pathogenic strains including the more mild CPs-V-A and more severe CPsV-B.[3] The virus is characterized by a single-stranded RNA molecule with a 48 kDa coat protein and a spiral filament structure.[4]

Common hosts of this disease are citrus and herbaceous plants like sweet orange, grapefruit, mandarin, and Mexican lime.[5] Symptoms of infected hosts consist of interveinal chlorotic flecks and leaf mottling in younger tissues–in more severe cases these symptoms persist in older tissues. In mild cases, the bark of the trunk or limbs may exhibit scaling and flaking. Later in the disease cycle, gum can permeate into the wood and form an irregular circular pattern. In more severe cases symptoms include rapid expansion of bark lesions, gum-impregnated lesions on twigs, and chlorotic patterns on fruit.[6]

Techniques used for the identification of citrus psorosis virus include the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that uses a specific antibody to determine the antigen, polymerase chain reaction to amplify target sequences, and detecting nucleic acids by lateral flow microarrays. Other methods commonly used are direct tissue blot immunoassays, fluorescence in-situ hybridization, immunofluorescence, and electron microscopy for viral pathogen detection.[7]

Citrus psorosis virus is often transmitted mechanically by infected budwood or contaminated tools. Additionally, the disease has the potential to proliferate through root grafting or infected seeds. The best management practices that can be implemented involve sourcing indexed and certified disease-free budwood, temporary recovery by pruning infected bark, host removal, and disinfection of machinery or equipment.[8]

Isolation

The Citrus psorosis virus Egyptian strain (CPsV-EG) was isolated from naturally infected citrus grapefruit (Citrus paradisi Macf.) at ARC. The grapefruit used for CPsV-EG isolatation was found to be free from CTV, CEVd and Spiroplasma citri by testing with DTBIA, tissue print hybridization and Diene's stain respectively.[9]

CPsV-EG isolate was transmitted from infected citrus to citrus by syringe and grafting and herbaceous plants by forefinger inoculation and syringe. The woody indicators and rootstocks were differed in response to CPsV-EG isolate which appeared as no-response, response, sensitivity and hypersensitivity. A partial fragment of RNA3 (coat protein gene) of CPsV-EG (–1140bp and –571bp) was amplified by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from grapefruit tissues using two sets primers specific CPsV (CPV3 and CPV4) and (PS66 and PS65) respectively. The virus under study was identified as CPsV-EG isolate according to biological, serological and molecular characters. The serological characters represented as the antigenic determinants of CPsV-EG isolate related to monoclonal antibodies specific CPsV strain where as appeared precipitation reaction by DAS-ELISA and DTBIA.[9]

CPsV-EG was detected on the basis of biological indexing by graft inoculation which gave oak leaf pattern (OLP) on Dweet tangor and serological assay by DAS-ELISA using Mab specific CPsV. CPsV-EG was reacted with variable responses on 16 host plants belonging to 6 families. Only 8 host plants are susceptible and showed visible external symptoms which appeared as local, systemic and local followed by systemic infections.[9]

Histology

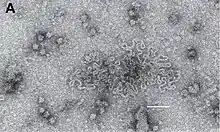

Young grapefruit leaves of both healthy and CPsV-EG infected plants have been studied histologically and ultrastructurally.[10]

In general CPsV-EG-infection affects the upper epidermis of the leaf which is composed of non-tabular parenchyma cells covered by a thin layer of cuticle. Crystal idioblast (CI) containing cells are lacking in the palisade layer and protrude into the epidermis. The oil glands are lacking compared with healthy leaf. Secondary growth occurs in midvein and major lateral veins in smaller veinlets. The vein endings consist of a single trachoid strand of elongated parenchyma cells enclosed by the bundle sheath compared with healthy ones.[10]

The ultrastructure of infected leaves showed a number of changes. Infected cells have large numbers of abnormal chloroplasts, mitochondria and hypertrophied nuclei. Cells of CPsV-EG infected citrus plants have abnormally elongated and curved mitochondria. The nuclei have several dark stained bodies, which are displaced toward nucleus periphery along the nuclear envelope. Sometimes nucleolus appear abnormally shaped. Inclusion bodies that may contain virus particles are also found.[10]

Strains

Three Egyptian isolates of Citrus psorosis virus (CPsV-EG)—ARC, TB and TN—were obtained from three citrus cultivars—Grapefruit, Balady and Navel—respectively. These isolates were differed in some of their external symptoms. The CPsV-EG isolates were detected by biological indexing, giving rise to Oak Leaf Pattern (OLP) on Dweet tangor. The three isolates were differentiated using Double Antibody Sandwich-Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (DAS-ELISA), woody indicator plants, differential hosts, peroxidase isozymes and activity, total RNA content and Reserves Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR). The severe isolate (ARC) gave the highest OD value (2.204) in ELISA, followed by the mild isolate (TB) (1.958) and the last latent isolate (TN) (1.669). These isolates differed also in incubation period, intensity of symptoms and response to sensitivity of woody indicator plants and differential hosts. The CPsV-EG isolates showed differences in isozymes fractions, RF value and intensity as compared with healthy plant. Results were confirmed by peroxidase activity where the level of peroxidase activity was considerably higher in ARC leaves than TB and the last TN. The total RNA content in infected leaves gave the highest content in ARC followed by TB isolate while the lowest was recorded in TN isolate. Finally, RT-PCR showed differences between CPsV-EG isolates of PCR products using specific primer (Ps66 and Ps65) where base number of coat protein gene ARC isolate 571 bp; TB isolate 529 bp and TN isolate 546 bp.[11]

References

- "ICTV Taxonomy history: Citrus psorosis ophiovirus". International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTV). Retrieved 14 January 2019.

- K. Djelouah, A.M. D'Onghia "Detection of citrus psorosis virus (CPsV) and citrus tristeza virus (CTV) by direct tissue blot immunoassay" Options Méditerranéennes (Mediterranean Agronomic Institute), Série B n. 33

- Trimmer, L.W., Gransey, S.M. and Graham, J.H (2000). "Compendium of citrus diseases".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Belabess, Z., Sagouti, T., Rhallabi, N., Tahiri, A., Massart, S., Tahzima, R., Lahlali, R., & Jijakli, M. H. (2020). "Citrus Psorosis Virus: Current Insights on a Still Poorly Understood Ophiovirus". Microorganisms. 8 (8): 1197. doi:10.3390/microorganisms8081197. PMC 7465697. PMID 32781662.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Trimmer, L.W., Gransey, S.M. and Graham, J.H. (2000). "Compendium of citrus diseases".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Dewdney, Megan. "Citrus Disease Spotlight: Psorosis" (PDF). Citrus Industry.

- Gautam, A.K., and Kumar S. (2020). "Techniques for the Detection, Identification, and Diagnosis of Agricultural Pathogens and Diseases". Natural Remedies for Pest, Disease and Weed Control. pp. 135–142. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-819304-4.00012-9. ISBN 9780128193044. S2CID 212893107.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Eskalen, A. and Adaskaveg, J.E. "Psorosis". UC IPM Pest Management Guidelines: Citrus UC ANR Publication 3441.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ghazal, S.A.; Kh.A. El-Dougdoug; A.A. Mousa; H. Fahmy and A.R. Sofy, 2008. Isolation and identification of Citrus psorosis virus Egyptian isolate (CPsV-EG). Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 73(2): 285–95.

- Sofy, A.R.; A.A. Mousa; H. Fahmy; S.A. Ghazal and Kh.A. El-Dougdoug, 2007. Anatomical and Ultrastructural Changes in Citrus Leaves Infected with Citrus psorosis virus Egyptian Isolate (CPsV-EG). Journal of Applied Sciences Research. 3(6): 485–494.

- El-Dougdoug, Kh.A.; S.A. Ghazal; A.A. Mousa; H. Fahmy and A.R. Sofy, 2009. Differentiation Among Three Egyptian Isolates of Citrus psorosis virus. International Journal of Virology. 5(2): 49–63.