Clan Macdonald of Sleat

Clan Macdonald of Sleat, sometimes known as Clan Donald North and in Gaelic Clann Ùisdein [kʰl̪ˠan̪ˠ ˈuːʃtʲɛɲ], is a Scottish clan and a branch of Clan Donald—one of the largest Scottish clans. The founder of the Macdonalds of Sleat was Ùisdean, or Hugh, a 6th great-grandson of Somerled, a 12th-century Lord of the Isles (Rì Innse Gall). The clan is known in Gaelic as Clann Ùisdein ("children of Ùisdean"), and its chief's Gaelic designation is Mac Ùisdein ("son of Ùisdean"), in reference to the clan's founder. Both the clan and its clan chief are recognised by the Lord Lyon King of Arms, who is the heraldic authority in Scotland.

| Clan Macdonald of Sleat Clann Ùisdein | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Motto | Per mare per terras (By sea and by land) | ||

| Profile | |||

| Region | Highland and Islands | ||

| District | Inverness-shire | ||

| Plant badge | Common heath[1] | ||

| Chief | |||

| |||

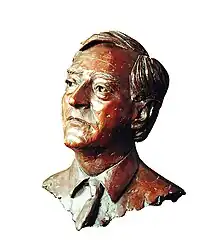

| Sir Ian Godfrey Bosville Macdonald of Sleat[2] | |||

| 17th Baronet of Sleat, 25th Chief of Macdonald of Sleat[2] (Mac Ùisdein[3]) | |||

| Seat | Thorpe Hall, Rudston, East Yorkshire, England[4] | ||

| Historic seat | Dunscaith Castle;[5] Duntulm Castle;[6] Armadale Castle[7] | ||

| |||

| |||

The Macdonalds of Sleat participated in several feuds with neighbouring clans, most notably the Macleods of Harris & Dunvegan and the Macleans of Duart. The clan also suffered from infighting in the early 16th century, as the leading members of the clan fought and murdered each other.

The clan seems to have grudgingly supported the Royalist cause in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and suffered grievously in military defeats against Parliamentarian forces. The clan supported the Jacobite cause in the 1715 rebellion, yet refused to come out for Bonnie Prince Charlie and his father a generation later in 1745. In the early 18th century, the clan's chief was involved in a plan to sell tenants into indentured servitude in the American Colonies. By the late 18th century, the chiefs had alienated themselves from the common clansfolk, when they seated themselves in northern England and rarely visited the old clan lands. The 18th and 19th centuries witnessed the suffering of the common clansfolk, as many were cleared off their lands at the hands of their absentee landlords. Today members and descendants of the clan live all over the world.

Sources

Much of the history of the Macdonalds of Sleat comes from traditional family histories, and it is often difficult, if not impossible, to tell fact from fiction.[8] The clan histories relevant to the Macdonalds of Sleat were composed by the shanachies (historians or story tellers) MacVuirich – the Clanranald shenachie – and Hugh Macdonald – the Sleat shenachie. Contemporary records that shed light upon the early history of the clan include charters and confirmations of charters granted by kings, and various bonds of manrent entered with other landlords and clan chiefs.

History of the Macdonalds of Sleat

.jpg.webp)

Origins

The Macdonalds of Sleat are a branch of Clan Donald — one of the largest Scottish clans.[9][10] The eponymous ancestor of Clan Donald is Domhnall, son of Raghnall, son of Somhairle.[11] Traditional Clan Donald genealogies, created in the later Middle Ages, give the clan a descent from various legendary Irish figures. Modern historians, however, distrust these traditional genealogies,[12] and consider Somhairle, son of Gille Brighde to be earliest ancestor for whom there is secure historical evidence.[13] Somhairle, himself, was a 12th-century leader, styled "king of the isles" and "king of Argyll";[14] yet there is no reliable account for his rise to power.[12]

The Macdonalds of Sleat descend from Domhnall's son, Aonghas Mór; and then from his son, Aonghas Óg. Angus Óg's son, Eoin, was the first Lord of the Isles. Eoin I's first marriage was to Áine, heiress of Clann Ruaidhrí (which was founded by Ruaidhrí, elder brother to Domhnall, founder of Clan Donald).[15] Eoin I later divorced Áine and married Margaret, daughter of Robert II. The children from Eoin I's first marriage were then passed over in the main succession of the chiefship of Clan Donald and later Macdonald lords of the isles, in favour of those from his second marriage.[16] Eoin I was succeeded by his son, Domhnall of Islay; who was in turn succeeded by his son, Alasdair of Islay. The Macdonalds of Sleat descend from Ùisdean, bastard son of Alasdair of Islay and the daughter of Ó Beólláin (O'Beolan), Abbot of Applecross. From Ùisdean, the Macdonalds of Sleat are also known in Gaelic as Clann Ùisdein ("the children of Ùisdein").[17]

15th century

The first record of Ùisdean occur in the traditional histories of the shenachie MacVurich and Hugh Macdonald. According to the Sleat shenachie, Ùisdean, along with several young men from the Western Isles went on a raiding expedition to Orkney. The tradition runs that the Western Islesmen were victorious in their conflict with the Northern Islesmen, and that the Earl of Orkney was also slain. Ùisdean is then said to have ravaged Orkney, and carried off much loot. According to Angus and Archibald Macdonald, Ùisdean's expedition took place around 1460, when he did not appear to hold title to any of the lands his family would come to hold. In fact, in the year 1463, Eoin II, Lord of the Isles granted Ùisdean's older brother, Celestine, the 28 merklands of Sleat, in addition to extensive lands in west Ross given to him in the previous year. In 1469, Ùisdean received from the Earl of Ross the 30 merklands of Skeirhough in South Uist; the 12 merklands of Benbecula, and the merkland of Gergryminis also in Benbecula; the 2 merklands of Scolpig, the 4 merklands of Tallowmartin, the 6 merklands of Orinsay, the half merkland of Wanlis, all in North Uist; and also the 28 merklands of Sleat. The earliest Clann Ùisdein seat connected with the barony of Sleat was Dunscaith Castle, off the Sound of Sleat. Ùisdean played not a small part in securing the surrender of the Earl of Ross, for which he was promised by the king 20 pounds worth of land, in 1476. The lordship of the isles was forfeited in 1493, and Ùisdean obtained a royal confirmation for his lands granted to him by the Earl of Ross in 1469. Ùisdean died in 1498, and was buried at Sand, in North Uist.

During his life, Ùisdean had several wives and several known children by other women.[5] Some of Ùisdean's sons would go on to play a large part in the history of the clan in the early 16th century. His eldest son, Eoin, would go on to succeed him.[5] Other notable sons included: Dòmhnall Gallach, son of the daughter of a prominent member of Clan Gunn (Caithness is called Gallaibh in Gaelic).[19] Another son was Dòmhnall Hearach, so-called from the fact his mother was a daughter of Macleod of Harris, and where he probably spent a portion of his early life; Aonghas Collach, so-called from the fact his mother was a daughter of Maclean of Coll; Gilleasbaig Dubh was the son of a daughter of Torquil Macleod of the Lewes; and Aonghas Dubh was the son of a daughter Maurice Vicar of South Uist.[20]

Early 16th century

.jpeg.webp)

On the year of his succession, Eoin resigned the lands and superiorities to the king. In consequence, the lands of Kendess, Gergryminis, 21 merklands of Eigg, and 24 merklands of Arisaig were then granted to Ranald Bane Allanson of Clanranald (chief of the Macdonalds of Clanranald). In 1498, the king granted to Alasdair Crotach (chief of Clan MacLeod) two unicates of the barony of Trotternish with the office of the bailiary of the whole lands thereof. Also the same year, the king granted Torquil MacLeod of Lewis (chief of Clan MacLeod of Lewis) the same bailiary of Trotternish which was granted to the chief of the Clan MacLeod, and also the 4 merklands of Terunga of Duntulm and 4 merklands of Airdmhiceolan. A and A Macdonald noted that during the minority of the Stewart kings in the 15 and 16th centuries many charters for the same lands were granted to several individuals. It is no wonder that in 1498 James IV revoked all charters given during the period prior to his coming of age. In 1505, Eoin resigned the lands of Sleat and North Uist, including Dunscaith Castle, to Ranald Allanson of Island Begrim. On his death, the chiefship of the clan passed to Dòmhnall Gallach, second son of Ùisdean.[22]

Because of the way in which his predecessor had granted away the clan lands, there is no contemporary record of Dòmhnall Gallach. The only record of Dòmhnall Gallach is from tradition. According to the Sleat shanachie, he was present at the Battle of Bloody Bay in 1484, and there fought on the side of Aonghas Óg against his father, Eoin, Lord of the Isles. Even though Dòmhnall Gallach's legal right to much his father's lands was given away by his predecessor, he and his brothers managed to physically hold on to their lands in Skye and Uist. Notwithstanding Clanranald's charter, Dòmhnall Gallach had his seat at Dunscaith Castle. Dòmhnall Gallach did not reign long as chief as he was murdered in 1506, by his brother, Gilleasbaig Dubh. The brothers Gilleasbaig Dubh, Aonghas Dubh and Aonghas Collach also conspired together and murdered their other half-brother, Dòmhnall Hearach, on the Inch of Loch Scolpig. Not long after the murders, Ranald Bane of Moydart forced Gilleasbaig Dubh to flee Uist, whereupon he participated in piratical career in the southern Hebrides for about 3 years. Gilleasbaig Dubh earned the favour of the Government by handing over similar pirates John Mor and Alister Bernich, of Clan Allister of Kintyre. After doing so he returned to the lands of Clann Ùisdein, assumed the leadership of the clan and took possession of the bailiary of Trotternish, all with the consent of the Government.[20]

Clann Ùisdein chaos

During the time of Gilleasbaig Dubh's piratical career, the traditional history of Clann Ùisdein is a tale of violence and lawlessness.[20] According to the Sleat shenachie, Aonghas Collach travelled to North Uist with a number of his followers and spent the night the home of Dòmhnall of Balranald (who was a member of the Siol Gorrie: descendants of Gorraidh (Godfrey), youngest son of Eoin and Ami MacRauiri).[20][23] Balranald happened to be away from home at the time, and that night Aonghas Collach attempted to rape his wife (who was a Macdonald of Clanranald). After her escape to South Uist, she alerted her friends and family. The result was that a body of 60 men, led by Donald MacRanald, and large contingent of Sìol Ghorraidh men marched north and surprised Aonghas Collach at Kirkibost. There 18 of Aonghas Collach's men were slain and he himself was taken prisoner. He was then sent to Macdonald of Clanranald, in South Uist, and tied up into a sack and cast into the sea. Another of Ùisdean's sons, Aonghas Dubh was also made prisoner by Macdonald of Clanranald, and was long held captive. One day he was permitted to run on the Strand of Askernish in South Uist, to see if he could run as well as he could prior to his incarceration. Aonghas Dubh then attempted flee his guards, however he was then wounded in the leg by an arrow. The wound was considered incurable and Aonghas Dubh was summarily put to death.[20]

Soon after his return, Gilleasbaig Dubh's took revenge on Sìol Ghorraidh for their treatment of Aonghas Collach, and put many of them to death. The manner of Gilleasbaig Dubh's death is also recorded by the Sleat shenachie. This account tells how Dòmhnall Gruamach, son of Dòmhnall Gallach, and his half-brother Raghnall, son of Dòmhnall Hearach, went to North Uist to visit Gilleasbaig Dubh who had murdered their father. One day, the two half-brothers, Gilleasbaig Dubh, and their henchmen, went hunting south of Lochmaddy. While the attendants were beating up the hill the three men sat waited for the game to appear. In time, Gilleasbaig Dubh eventually fell asleep and Raghnall killed his uncle. A and A Macdonald gave the date of Gilleasbaig Dubh's murder at probably about 1515–1520.[24]

Mid to late 16th century

Dòmhnall Gallach succeeded to the chiefship after the death of Gilleasbaig Dubh. In 1521, the chief rendered a bond of manrent to Sir John Campbell of Cawdor. A and A Macdonald stated that this bond may have led the Sleat chief to follow Cawdor, in 1523, on the Duke of Albany's campaign against England. The campaign did not go well for the two chiefs, as both Sleat and Cawdor's names are recorded on a remission for leaving the field of battle during the siege of Wark Castle. A and A Macdonald also stated that it was likely on their return from the borders that Cawdor and his followers (including Sleat) murdered Lachlann Cattanach Maclean of Duart, in Edinburgh. In 1524, Dòmhnall Gruamach entered into an alliance with the chief of Clan Mackintosh; and later in 1527, he entered into bonds with Mackintosh, Munro, Rose of Kilravock and Campbell of Cawdor. In 1528, Dòmhnall Gruamach received considerable support from his half-brother, Iain, son of Torquil, chief of Clan Macleod of Lewis. That year their combined forces were successful in driving out the Macleods of Harris & Dunvegan, and their vassals, from the barony of Trotternish. Dòmhnall Gruamach, in return, then aided Macleod of Lewis in obtaining effective possession of Lewis. Macleod of Harris & Dunvegan then appealed to the Privy Council, and that year a summons was issued to the chiefs of Sleat and Lewis. As conflicts in the Hebrides increased over time, the Privy Council ordered the chieftains of the isles to appear before the king in 1530. The following year Sleat, Macleod of Harris & Dunvegan, and Mackinnon of Strathardill were frequently cited before Parliament but failed to appear. After 1530, Dòmhnall Gallach's chiefship seems to have been uneventful and peaceful, as there is no record of his name in state records until his death, in about 1537.[25]

The chiefship of the clan then passed to Dòmhnall Gallach's son, Dòmhnall Gorm.

Dòmhnall Gorm was killed at Eilean Donan in 1539 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Dòmhnall Gormeson. As Dòmhnall Gormeson was only a child at the time of his father's death, the leadership of the clan went to his granduncle, Gilleasbaig Clèireach, son of Dòmhnall Gallach. According to the Sleat shenachie, the Privy Council made a strong attempt to apprehend the young chief during his minority. The traditional history has it that he was sent to the safety of Ruairidh Macleod of Lewis. Though afterwards, Gilleasbaig Cleireach took Dòmhnall Gormeson to England, where the young chief lived for several years. In 1554, with anarchy prevailing in the Highlands, the Queen Dowager took control of the Government and attempted to restore peace and order. Her lieutenants, Argyll and Huntly, were ordained by the Privy Council to passify the most unruly chiefs, among these was Dòmhnall Gormeson. Shortly afterwards, Dòmhnall Gormeson appears to have submitted to the Government, and for about 8 years obediently ceased to quarrel with his neighbouring chiefs. However, by 1562, he is recorded among others Macdonalds, as receiving a remission form Queen Mary for the destruction and slaughter committed in the Maclean lands of Mull, Tiree and Coll. A and A Macdonald were unsure of the nature of these raids, though proposed that they may have something to do with a quarrel of Clann Iain Mhòir and Maclean of Duart, regarding the Rinns of Islay. In 1568 he joined Somhairle Buidhe MacDhòmhnaill and his Irish campaigning. The next year he was feuding with the Mackenzies of Kintail.[26] Dòmhnall Gormeson died in 1585, and was succeeded by his oldest son, Dòmhnall Gorm Mòr.[7]

Late 16th century

Dòmhnall Gorm Mòr was still a minor at the time of his father's death. The young chief was placed under the guardianship of his granduncle, Seumas of Castle Camus. In 1575, Seumas of Castle Camus agreed to pay the dues owing in the lands of North Uist, Sleat, and Trotternish, which had been owed to the Bishop of the Isles since the death of Dòmhnall Gormson. This document shows that Seumas of Castle Camus and Clann GhillEasbaig Chlèireach ("the children of Gilleasbaig Clèireach") had divided up the lands of the Macdonalds of Sleat. A and A Macdonald stated that Clann GhillEasbaig Chlèireach possessed themselves of Trotternish (with Dòmhnall, son of Gilleasbaig as bailie of the region); while Seumas of Castle Camus held the bailiary of Sleat. For the year 1580, there is evidence that the possessors of clan estates were behind in their payments to the Bishopric of the Isles and the Iona Abbey — so much so that an Act of Council and Session was passed ordering a summons against Dòmhnall and Ùisdean, sons of Gilleasbaig Cleireach. The following year Seumas of Castle Camus and Clann GhillEasbaig Chlèireach were declared rebels, and forfeited for their failure to pay their dues, and their escheat was granted to the Bishop of the Isles.[27]

In 1585, Dòmhnall Gorm Mòr and his retinue were sailing to visit Macdonald of Dunivaig & the Glens of Antrim, but were forced to take shelter in Jura, which was then divided between Maclean of Duart and the chief of Clann Iain Mhòir. Unluckily for the Macdonalds of Sleat, they landed on Maclean of Duart's portion of the island. That night they were attacked by a large body of Macleans, at a place called Inbhir a' Chnuic, and tradition states that 60 of them were slain and that the chief had only escaped because he had fallen asleep upon his galley. This conflict was only the beginning of a bloody feud between the Macdonalds of Sleat and the Macleans of Duart. It is not certain exactly what conflicts transpired, though by September 1585, James VI had written to Ruairidh Mòr Macleod of Harris & Dunvegan, requesting him to assist Maclean of Duart against the Macdonalds who had done Maclean of Duart much injury and were threatening even more. By 1589, the feud had come to an end. The next year, the Sleat chief, and his brothers Gilleasbaig and Alasdair, his granduncle Seumas of Castle Camus, and Ùisdean, son of GillEasbaig Clèireach, received a remission for all crimes committed against the Macleans of Duart. On the power of this dispensation, Dòmhnall Gorm Mòr, Sir Lachlann Mòr Maclean of Duart, and Angus Macdonald of Dunivaig and the Glens of Antrim, were all induced to go to Edinburgh to consult the king. On their arrival they were apprehended and imprisoned, and the king and council imposed heavy fines as a condition of their release. Dòmhnall Gorm Mòr was to promise to give up £4,000 and to pledge his obedience to the Scottish Government, as well as the Irish Government of Elizabeth I.[27]

In the summer of 1594, Dòmhnall Gorm Mòr and Ruairidh Mòr Macleod of Harris & Dunvegan each sailed for Ulster at the head of 500 men each. They force was intended to support Aodh Rua Ó Domhnaill who was besieging Enniskillen Castle. Later in 1595 another expedition of Hebridians was made to support the Irish rebels against the forces of Elizabeth I. Dòmhnall Gorm Mòr raised a fighting force of 4,000 men and sailed to Ulster in a fleet of 50 galleys and 70 supply ships. The fleet was however blown off course and was attacked off Rathlin Island by 3 English frigates. 13 Macdonald galleys were sunk and another 12 or 13 were destroyed or captured off Copeland Island, at the entrance to Belfast Lough.[29]

Bitter feuding with Macleod of Harris & Dunvegan

.jpeg.webp)

Not long after returning from Ireland, a feud seems to have arisen between Dòmhnall Gorm Mòr and the chief of Clan Macleod, Ruairidh Mòr. The Sleat chief had married the sister of the Macleod chief, and after some time sent her back to Macleod. Tradition has it that she was blind in an eye, and was mounted upon one-eyed horse, followed by a one-eyed dog, and accompanied by a one-eyed man.[7] The Macleod chief was outraged and immediately had Trotternish ravaged. The Macdonalds of Sleat then retaliated by attacking Macleod possessions in Harris. This then led to Ruairidh Mòr leading a warband of 60 men on a raid in North Uist.[30] The Macleod chief's relative, Mac Dhòmhnaill Ghlais ("the son of Dòmhnall the grey"),[note 1] and 40 followers managed to possess themselves of the goods that the Uistfolk has hidden in Teampull na Trionaid ("trinity church"), at Carinish. However, the Macleods were attacked by a celebrated Clanranald warrior, named Dhòmhnall MacIain 'Ic Sheumais, in command of 15 men. The Macleods were outmanoeuvred by Dhòmhnall MacIain 'Ic Sheumais, and were slain almost to a man. Mac Dhòmhnaill Ghlais and a few of his followers fled for the island of Baleshare, but were run-down by some Uistmen and killed on the spot which ever since been known as Oitir Mhic Dhòmhnaill Ghlais ("the strand of the son of Dòmhnall the grey").[7]

The feud then became even more vicious, with both sides constantly raiding one another's territories, and the common clansfolk caught up in the middle of the warring were reduced to such an extent that they were even forced to eat dogs and cats to sustain themselves. The Macdonalds of Sleat later made one final strike against the Macleods. At the time, Ruairidh Mòr was away seeking assistance from Archibald Campbell, 7th Earl of Argyll. Seizing upon the moment, Dòmhnall Gorm Mòr, led an all out invasion of Minginish and Bracadle, in the north of Skye. The Macdonalds took much spoil in the form of cattle and drove them to Coire na Creiche, overlooking the Cuillin hills. Here the Macleods mustered themselves, led by Alasdair, brother of the Macleod chief. The Battle of Coire Na Creiche lasted into the night and when the fighting subdued the Macleods were utterly defeated in what has since been the last clan battle to have ever have been fought on the Isle of Skye.[30] By now, Dòmhnall Gorm Mòr and Ruairidh Mòr's feud had escalated to such an extent that the Privy Council interfered, and ordered the two chiefs to disband their forces. The Macleod chief was ordered to surrender himself to the Earl of Argyll and the Sleat chief to George Gordon, 1st Marquess of Huntly. Not long afterwards the two chieftains were reconciled with each other by mutual acquaintances. Through meetings and Eilean Donan and Glasgow, it was agreed that peace should be preserved. By the end of 1601, the bloody feud, between Ruairidh Mòr and Dòmhnall Gorm Mòr, had come to an end.[7][30]

Early 17th century

In 1608 after a century of feuding which included battles against the Clan Mackenzie and Clan Maclean all of the relevant Macdonald chiefs were called to a meeting with Lord Ochiltree who was the King's representative. Here they discussed the future Royal intentions for governing the Isles. The chiefs did not agree with the king and were all thrown into prison. Donald, the chief of the Macdonalds of Sleat, was incarcerated in the Blackness Castle. His release was granted when he at last submitted to the King. Donald died in 1616 and then Sir Donald Macdonald, his nephew succeeded as the chief and became the first Baronet of Sleat.

Mid-17th century: civil war

Sir James Macdonald, 2nd Baronet of Sleat, had just succeeded his father, in 1644, when civil war broke out in the British Isles. At the time the population of his estates was estimated to have been about 12,000, and in consequence he would have been a power to be reckoned with within the Highlands. According to A and A Macdonald, it seems that the baronet had not been very enthusiastic for the royal cause. In the autumn of 1644, when Alasdair MacColla arrived on the west coast, with Irish auxiliaries supplied by the Marquess of Antrim, he offered command to Sleat, yet Sleat declined the offer. Following the battle at Inverlochly, Montrose marched northwards. Shortly before the Battle of Auldearn, Montrose wrote to the Laird of Grant, informing him that, among others, 400 of the baronet's men had joined him. It is unknown who led the Macdonald of Sleat contingent, or what part they played in the campaign. A and A Macdonald considered it probably that the Sleat men fought under the command of the baronet's brother, Donald Macdonald of Castleton. The Sleat men continued with the campaigning following the defeat at the Battle of Philiphaugh. They took part in the siege of Inverness. When the king surrendered to the Scottish Army at Newark, and ordered Montrose to disband his forces, the Sleat men returned home to Skye and Uist. The baronet then made terms with the Committee of Estates, for himself and his principal followers who had taken part in the insurrection. The Duke of Hamilton marched down to recover the king. The Hebridean men had mustered in large numbers and were a part of the force which was defeated at the Battle of Preston in 1648. After the expedition had failed, the engagers were replaced in the Government by a new Committee of Estates, with Argyll at their head. In 1649, the baronet was cited to find caution for good behaviour. The baronet took no notice. In the summer of 1650, Charles II arrived in Scotland and was crowned at Scone. In expectation of Cromwell's advance, he appealed for support to his Highland supporters. The baronet was given a commission to levy a regiment on his estates in Uist and Skye-which was completed in January, 1651 and then marched to support the king. At the Battle of Worcester they formed a part of the Highland wing of the army. The Sleat men and the Macleods suffered severely in the battle, and only a remnant ever returned to their homes in the isles. After the defeat, the king fled to the continent, and the baronet made peace with Commonwealth of Scotland. Later the baronet refused to aid the Earl of Glencairn and others in 1653. He was hard pressed by his former allies, notably Glengarry who was a noted loyalist.[32] The 2nd baronet died in 1678 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Donald Macdonald, 3rd Baronet of Sleat.[7]

Late 17th century

In the decade following the death of James there is little record of the Macdonalds of Sleat. The chief, the 3rd baronet, was in ill health and seems to have lived a quiet life. In 1685, Argyll and others landed in the Western Isles and the Privy Council ordered Sir Donald to raise 300 men, and have them in Loch Ness in June. The insurrection however came to an abrupt end when Argyll was executed, and the Sleat men returned home before the end of June without seeing battle. When Dundee appealed to the Highland chiefs for their support to James VII, Sleat was among the first to join at the head of 500 men. The 3rd baronet however became ill just as he reached Lochaber, and the Sleat men were led by his son, Donald. At the Battle of Killiecrankie, the Sleat battalion was posted on the extreme left wing and suffered severely during the ensuing conflict. Among the slain were five of the principal officers, all cadets of the Macdonalds of Sleat. With the collapse of the rebellion, after the Highland men had returned home, the Government made an effort to treat with the Macdonalds of Sleat. While the baronet's son, who had led the clan in battle during the rising, was willing to consent under certain terms, the baronet remained stubborn and refused to communicate with William II's emissaries. After a while the Government took steps to force the chief into obedience, and two frigates were sent to Skye. After fruitless efforts at negotiating the frigates began shelling two of the chief's houses, burning them to the ground. Lowland troops then landed and fought with Sleat's men, though were forced back to their ships, suffering 20 dead. In time he came to peace with the Government, though it is unknown what were the manner or terms of the surrender. The Macdonalds of Sleat were on friendly terms with the garrison at Fort William, yet were at odds with other Macdonalds. In 1694, the chief and Macdonald of Camuscross made a complaint to the Supreme Council against, Alexander Macdonald, Younger of Glengarry; Aeneas Macdonald, his brother; and several others in Knoydart. Sleat and Camuscross claimed that the men had conceived "ane deadly hatred and evil will" against them, committing acts of violence against them and their possessions. The 3rd baronet died at Armadale in 1695 and was succeeded by his son, Sir Donald Macdonald, 4th Baronet.[33]

18th century

_Sir_Donald_Macdonald_of_Sleat%252C_4th_Baronet.jpg.webp)

The 4th baronet distinguished himself as leader of the clan in his father's lifetime. From the beginning of the 18th century to the eve of the Jacobite rebellion in 1715, he lived in Glasgow, and had no contact with his clan in the Hebrides. During this period, according to A and A Macdonald, it would appear that he was in close contact with the Jacobite factions. The 4th baronet was not present at the Jacobite gathering at Braemar in September, when the standard was raised by the Earl of Mar. He travelled to Skye to raise his followers, which have been estimated from 700 to 900 men. In around the beginning of October, the baronet at the head of his men, joined the Earl of Seaforth at Brahan, and together proceeded to Alness. They put to the flight the Earl of Sutherland, with the Sutherland and Reay men, the Monros, Rosses and others. The baronet fell ill and returned to Skye, leaving command of the Sleat men to his brothers, James and William. When Government troops were sent to Skye the baronet then fled to North Uist. In April 1716, the baronet offered to surrender himself in term of the recently passed Act of Parliament, pleading that he was not healthy enough to travel to Inverlochy to surrender in person as the act required. However, when he failed to appear he was found guilty of high treason, and his estates were accordingly forfeited[34] (however his titled does not appear to have been forfeited). The Commissioners of Forfeited Estates then proceeded to survey the baronet's estates. The survey found that the clan lands were in very poor condition and the people were in extreme poverty. For example, the tenants of North Uist had lost 745 cows, 573 horses and 820 sheep by a plague. The sea, too, had overflowed in parts of the land and destroyed many houses. The Skye estates were in similar condition with the loss of 485 horses, 1,027 cows and 4,556 sheep. The 4th baronet died in 1718 and was succeeded by his only son, Donald.[34]

Immediately following his father's death, the 5th baronet petitioned the Court of Session to rule that his father had indeed obeyed the Act of Parliament, by submitting his written surrender to the Government. The Court of Session ruled in favour of the baronet, and that he had not been forfeited of his estates. The Forfeited Estates Commissioners however appealed to the House of Lords, who subsequently ruled in favour of the appellants. The baronet died young, in 1720, and was succeeded by his uncle, James Macdonald of Oronsay.[note 2] The 6th baronet had served the clan at the Battle of Killiecrankie, and led the Sleat men at the Battle of Sheriffmuir. Despite his support to the Jacobite cause, he supported George I in 1719 during the Spanish invasion which ended at the Battle of Glen Shiel. The 5th baronet outlived his nephew by only a few months, and died in 1720.[35]

_Sir_Alexander_Macdonald_of_Sleat%252C_7th_Baronet.jpg.webp)

During the forfeiture of the clan's estates, the children of Sir James petitioned Parliament, in which they were successful, to receive £10,000 out of the estate of the deceased Donald. At the same time, provisions were also made for the widow and children of Donald. In 1723, Kenneth Mackenzie, an Edinburgh advocate, purchased the three baronies of Sleat, Trotternish and North Uist for £21,000. After deducting the provisions to the families of Donald and James, and the debts due to the wadsetters and others, the purchase price was nearly exhausted, and only £4,000 went to the public. General Wade's report on the Highlands in 1724, estimated the clan strength at 1,000 men.[36] In 1726. Kenneth Mackenzie and Sir Alexander Macdonald, 7th Baronet, the heir male, entered into a contract of sale, whereby the whole estate which had belonged to Sir Donald was sold to Sir Alexander. In 1727, Sir Alexander received a Crown charter for his lands, erecting the whole into a barony – called the Barony of Macdonald.

Sir Alexander was implicated in the abduction of Rachel Chiesley, Lady Grange, who was held on the Macdonald-owned Monach Isles between 1732 and 1734, before being moved on to St. Kilda.[37] In 1739, he was involved in the kidnapping of men and women from the Hebrides, with the intent of selling them into indentured servitude in North America (see relevant section below).

The 7th baronet was notable among Macdonald chiefs in refusing to join the 1745 Jacobite rising. His voiced his reasoning to Macdonald of Clanranald, stating the uprising was inopportune, with the chance of any success remote. A and A Macdonald noted that he would have also been grateful to the reigning House of Hanover, for the restoration of the clan's estates, which had been forfeited in the last rebellion. During the rising the 7th baronet raised two Independent Highland Companies for the Government cause.[38] The 7th baronet died in Bernera, in 1746, and was buried at Kilmore, in Sleat. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Sir James.[38]

The 8th baronet suffered from ill health as a child and while still comparatively young he was injured in a hunting accident. He attempted to regain his health in a warmer climate, when he left the British Isles for Italy, in 1765. His health, however, finally failed him in 1766, when he died in Rome, where he was buried.[7][39] He was succeeded by his brother, Alexander, who was at the time, an officer in the Coldstream Guards.[39] A and A Macdonald described the 9th baronet as being of a completely different temperament than that of his older brother. They described his tastes as "if note wholly English, at least entirely anti-Celtic". The 9th baronet raised the rents upon his estates, and evicted many of the poorer tenants from their holdings. During his chiefship, several tacksmen in Skye and Uist gave up their leases and emigrated. When Boswell and Johnson visited Skye in 1773, they encountered an emigrant ship, filled with tacksmen and their tenants, about to set sail. In 1776, the 9th baronet was made Lord Macdonald in the Peerage of Ireland. In 1777, he offered to raise a regiment on his estates, which the Government accepted. The regiment was named the 76th Regiment of Foot (Macdonald's Highlanders) and was 1,086 men strong; 750 of whom were from the baronet's lands on Skye and North Uist.[40] The Macdonalds were well represented in the officers of the unit with men from the families of the Macdonalds of Glencoe, Morar, Boisdale and others.[41] The regiment embarked for New York, in 1779, and served with distinction the American Revolutionary War. It returned home, and was disbanded in 1784. In 1794, the baronet raised three volunteer companies in Skye and Uist, for the defence of the country and relief of the regular army.[40] He married Elizabeth Diana, eldest daughter of Godfrey Bosville of Gunthwaite, (in the County of York, England). He died comparatively young, in 1795, and was succeeded by his eldest son, Alexander Wentworth.[7][40]

19th century to present

Alexander died in 1795 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Alexander Wentworth Macdonald, 2nd Baron Macdonald. The 2nd baron lived for the most of his life in England and abroad, and consequently associated little with the tenants on his Hebridean estates. In 1798, he received permission from George III to raise a regiment on these estates; however the islanders were unwilling to join, and very considerable pressure was brought to bear upon them before the full complement of men was finally recruited. He erected the mansion house at Armadale, in Sleat, which was the principal seat of his family.[7] The 2nd baron died unmarried in 1824 and was succeeded by his brother, Godfrey Bosville – Macdonald, 3rd Baron Macdonald. The 3rd baron was baptised as Godfrey Macdonald, and legally changed his name to Godfrey Bosville, in 1814. After succeeding his brother in 1824, he changed his name to Godfrey Bosville – Macdonald. The 3rd baron had served in the British Army prior to his succession and eventually rose to the rank of lieutenant-general, in 1830. He was also involved in a controversial dispute over the chiefship with Glengarry, which took place privately and publicly in the press.[7] He died in 1832 and was succeeded by his second eldest son, Godfrey William Wentworth Bosville – Macdonald, 4th Baron Macdonald. Under the 4th baron, vast portions of the clan inheritance were sold off, including North Uist and Kilmuir in Trotternish which included Duntulm Castle.[7] He died in 1863 and was succeeded by his eldest son, Somerled James Brudenell Bosville – Macdonald, 5th Baron Macdonald. The 5th baron died in 1874, aged 25, and was succeeded by his brother, Ronald Archibald Bosville – Macdonald, 6th Baron Macdonald. The 6th baron was succeeded by his grandson, Alexander Godfrey Bosville – Macdonald, 7th Baron Macdonald, who was in turn succeeded by his son, Godfrey James Macdonald, 8th Baron Macdonald. The 8th baron is the current chief of the name and arms of Macdonald and high chief of Clan Donald.

Illegitimacy and inheritance: modern chiefship

The current chiefs of Clan Donald and Clan Macdonald of Sleat both descend from the 3rd baron (Macdonald of Macdonald from his second son; Macdonald of Sleat from his eldest son). This reason for this is because the 3rd baron's eldest son, Alexander William Robert Macdonald, was considered to be illegitimate under English Law.[44] In consequence, the eldest son could not inherit the title Baron Macdonald in the Peerage of Ireland. However, since the baronetcy (Baronet of Sleat) was a Scottish title, it was later ruled in 1910, that the eldest son could succeed to that instead.[45]

The 3rd baron had married an illegitimate daughter of William Henry, Duke of Gloucester, in 1803; and the 3rd baron's eldest son, Alexander William Robert Macdonald, was born before that, in 1800.[11] In 1832, Alexander William Robert Macdonald had his name legally changed to Alexander William Robert Bosville. Later in 1847, he inherited his father's Bosville estates in Yorkshire, England. In consequence, he remained in Yorkshire and his younger brother, Godfrey William Wentworth Bosville–Macdonald, 4th Baron Macdonald, inherited the Scottish estates, titles, and chiefship. In 1910, Alexander Wentworth Macdonald Bosville, grandson of Alexander William Robert Bosville, obtained a decree from the Court of Session, which declared that Alexander William Robert Bosville was the eldest lawful son of the 3rd baron, and was accordingly the rightful heir.[3][11] He then changed his name to Alexander Wentworth Macdonald Bosville–Macdonald and was recognised as the 14th Baronet of Sleat, as such became the 22nd chief of Macdonald of Sleat.[3] He died in 1933 and was succeeded by his son, Godfrey Middleton Bosville–Macdonald of Sleat; who was in turn succeeded by his son, Alexander Somerled Angus Bosville–Macdonald of Sleat; who was succeeded by Ian Godfrey Bosville Macdonald of Sleat, 17th Baronet – the current chief of the clan. The chiefly family has been seated at Thorpe Hall, Rudston, East Yorkshire since the 3rd baron's eldest son inherited the Bosville estates in the 18th century.[3]

Forced emigration and the Ship of the People

In 1739, the 1st baron was involved in the infamous kidnapping of men and women from Skye and Harris, with the intention of transporting them to the American Colonies and selling them off as indentured servants. Other prominent men involved were Norman Macleod of Dunvegan (chief of Clan MacLeod), Donald Macleod of Berneray and his son Norman Macleod. During the night, Macleod of Berneray's son, Norman, arrived at Skye with a ship which has ever since been known as Soitheach nan Daoine ("the Ship of the People").[46][47] He then proceeded to force on board men, women, and children, from all levels of society. As the ship sailed towards North America with its human cargo, it was driven by a storm onto the northern coast of Ireland and wrecked. The passengers were however rescued, and most of them settled on the lands of the Earl of Antrim, though a few, after great difficulties managed to return to their homes in the Hebrides.[46][48][49]

The 4th baron and chief of the Macdonalds of Sleat, presided over one of the more notable forced evictions of Highlanders during the era of the Highland Clearances.[50] Those that drew particular controversy were the forced evictions of the small community of Sollas, in North Uist, in 1849 and 1850.[51] During the 1849 evictions rioting broke out in which the Uist women played a prominent role.[52] During the 1830s, tenants were cleared from his estates on Skye; and during the years 1838 and 1843, 1,300 people were removed from their homes in North Uist, to be replaced by sheep.[51] Several of the Sollas rioters were arrested and eventually found guilty, yet the jury made the following written comments afterwards:

...the jury unanimously recommend the pannels to the utmost leniency and mercy of the Court, in consideration of the cruel, though it may be legal, proceedings adopted in ejecting the whole people of Solas from their houses and crops without the prospect of shelter, or a footing in their fatherland, or even the means of expatriating them to a foreign one...[53]

Clan profile

- Clan chief: The current chief of the clan is Sir Ian Godfrey Bosville Macdonald of Sleat, 17th Baronet of Sleat. He is the 25th chief of Clan Macdonald of Sleat.[2][3] The chief's Gaelic designation is Mac Ùisdein ("son of Ùisdean"), which relates to his descent from Ùisdean of Sleat. The chief's sloinneadh (or pedigree) is: Shir Iain Gorraidh mac Alasdair Somhairle mhic Gorraidh 'ic Alasdair Uilleam 'ic Gorraidh 'ic Alasdair Uilleam 'ic Gorraidh 'ic Alasdair 'ic Alasdair 'ic Seumais 'ic Dòmhnaill Breac 'ic Seumais Mhor 'ic Dòmhnaill Gorm Òg 'ic GillEasbaig Clèirich 'ic Dòmhnaill 'ic Dòmhnaill Gorm 'ic Dòmhnaill Gruamach 'ic Dòmhnaill Gallach 'ic Ùisdean 'ic Alasdair 'ic Dòmhnaill 'ic Eoin 'ic Aonghais Òg 'ic Aonghais Mhòr 'ic Dòmhnaill 'ic Raghnaill 'ic Somhairle.[3]

- Chiefly arms: The current chief's coat of arms is blazoned: Quarterly first, argent a lion rampant gules armed and langued azure; second, Or a hand in armour fessways proper holding a cross crosslet fitchée gules; third, Or a lymphad sails furled and oars in action sable flagged gules; fourth, vert a salmon naiant in fess proper. Crest: A dexter forearm in armour fessways proper the hand proper holding a cross crosslet fitchée gules. Motto: Per mare per terras (by sea and land). Supporters: Two leopards proper collared Or.[3] The chief's heraldic standard consists of: The arms of Macdonald of Sleat in the hoist and of two tracts argent and gules, upon which is depicted the crest in the first and second compartments, and two sprigs of common heather in the third compartment, along with the motto "per mare per terras" in letters gules upon two transverse bands argent.[54] The coat of arms was matriculated at the Court of the Lord Lyon in 2000.[3] The chief's motto (per mare per terras) translates from Latin as "by sea and land".[55] The chief's slogan is carna, which is the name of a small island (Càrna) on Loch Sunart. Càrna was where Donald Balloch rallied the clan in 1431 before the Battle of Inverlochy, and also where Donald Dubh lead his last insurrection in 1545.[3]

- Clan member's crest badge: The crest badge suitable for members of the clan contains the chief's heraldic crest and motto. The crest is: A hand in armour fesswise holding a cross crosslet fitchée gules. The motto is: per mare per terras.[55]

- Clan badge: The clan badge or plant badge attributed to the clan is common heath. This plant is attributed to the other Macdonald clans and some other associated clans such as Clan MacIntyre and the Macqueens of Skye.[1]

- Origin of the surname: There are many variations of the surname Macdonald. The surname is an Anglicisation of the Gaelic Mac Dhomhnuill, which is the patronymic form of Domhnall. This Gaelic personal name is composed of the elements domno "world" and val "might", "rule".[56] According to Alex Woolf, the Gaelic personal name is probably a borrowing from the British Dyfnwal.[57]

- Pipe music: There are several pipe tunes specifically associated with the clan. Two pipe tunes were composed by Ewen Macdonald, for Sir James Macdonald, 8th Baronet. These were Cumha na Coise and Sir James Macdonald of the Isle's Salute.[39]

See also

- Sleat History

- Macdonald baronets

- Macdonald, things named Macdonald on Wikipedia

Notes

- The 20th century Clan Macleod historian, Rev. Donald MacKinnon, stated that according to some writers this cousin of the chief referred to, was Donald Macleod of Drynoch (also known as Donald Glas). MacKinnon stated this view likely stemmed from Sir Robert Gordon's 17th century work, which states that Roderick Mor Macleod sent his cousin, Donald Glas Macleod, to take possession of the spoil during the North Uist raid. MacKinnon points out that Uist tradition, however, gives the man's name as "MAC DHOMHNUILL GHLAIS (Donald Glas' son)", who was a grandson of Alasdair Crotach, 8th of Dunvegan. Furthermore, MacKinnon stated that Macleod of Drynoch could not have been the Macleod that took part in the raid as he would have been far too young and was only distantly related to the chief.[31]

- Which Oronsay?

References

- Adam; Innes of Learney 1970: pp. 541–543.

- "Bosville Macdonald of Sleat, Chief of Macdonald of Sleat". Burke's Peerage and Gentry. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- "Sir Ian Macdonald of Sleat". highcouncilofclandonald.org. Retrieved 27 May 2009.

- "Clan Chiefs". Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 1–6.

- "Skye, Duntulm Castle". CANMORE. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 38–46.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 1: p. 1.

- Newton 2007: p. 37.

- "Pledge to launch clan gathering". BBC News Online. 22 October 2007. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- Eyre-Todd 1923, 1: pp. 232–243.

- Woolf, Alex (2005). "The origins and ancestry of Somerled: Gofraid mac Fergusa and 'The Annals of the Four Masters'" (PDF). University of St Andrews. Retrieved 24 May 2009.

- Woolf 2007: p. 299.

- Brown 2004: p. 70.

- Duffy 2007: pp. 77–85.

- Eyre-Todd 1923, 2: pp. 269–270.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 467–479.

- "Skye, Dun Scaich". CANMORE. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- MacDonald of Castleton, Donald J (1977). "Galleys at Kishorn". clandonald.org.uk. Clan Donald Magazine No 7 (1977) Online. Archived from the original on 10 August 2007. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 9–15.

- Roberts 2000: pp. 4–5.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 6–9.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 359–360.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 15–16.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 16–19.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 20–27.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 27–38.

- "Skye, Knock Castle". CANMORE. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- Roberts 1999: p. 106.

- Roberts 1999: pp. 140–141.

- "Donald Macleod (I of Drynoch)". macleodgenealogy.org. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 58–69.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 69–79.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 79–82.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 82–84.

- Johnston, Thomas Brumby; Robertson, James Alexander; Dickson, William Kirk (1899). "General Wade's Report". Historical Geography of the Clans of Scotland. Edinburgh and London: W. & A.K. Johnston. p. 26. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- Macaulay, Margaret (2010), The Prisoner of St. Kilda: The True Story of the Unfortunate Lady Grange, Luath Press Ltd.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 84–92.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 92–98.

- Macdonald; Macdonald 1900, 3: pp. 98–101.

- Maclauchlan; Wilson 1875: pp. 520–522.

- "Armadale Castle". clandonald.com. Archived from the original on 4 August 2004. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- "Welcome". clandonald.com. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- "Clan Macdonald of Sleat". Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- "The Barony of MacDonald". baronage.co.uk. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- "Norman Macleod (VI of Berneray)". macleodgenealogy.org. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- "BBC Scotland Autumn 2007". BBC Online. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

- "The Hebridean ‘slaves’ offered for £3 a head"

- "Soitheach na Daoine". Comunn Eachdraidh Bheàrnaraigh. Retrieved 9 May 2017.

- Campey 2005: p. 122.

- Richards 1982: p. 420.

- Richards 2007: p. 71.

- Richards 2007: p. 185–186.

- "MacDonald of Sleat". myclan.com. Archived from the original on 21 May 2006. Retrieved 13 June 2009.

- George Way of Plean; Squire 2000: p. 174.

- "McDonald Name Meaning and History". Ancestry.com. Retrieved 2 June 2009.

- Woolf 2007: p. xiii.

Sources

- Brown, Michael (2004). The Wars of Scotland, 1214–1371 (illustrated ed.). Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1238-6.

- Campey, Lucille H (2005). The Scottish Pioneers of Upper Canada, 1784–1855. Toronto: National Heritage Books. ISBN 1-897045-01-8.

- Duffy, Seán, ed. (2007). The World of the Galloglass: War and Society in the North Sea Region, 1150–1600. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-85182-946-0.

- Eyre-Todd, George (1923). The Highland clans of Scotland; their History and Traditions. Vol. 1. New York: D. Appleton.

- Eyre-Todd, George (1923). The Highland clans of Scotland; their History and Traditions. Vol. 2. New York: D. Appleton.

- Fox, Adam; Woolf, Daniel R, eds. (2002). The Spoken Word: Oral Culture in Britain, 1500–1850 (illustrated ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-5747-7.

- Macdonald, Angus; Macdonald, Archibald (1900). The Clan Donald. Vol. 1. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company, Ltd.

- Macdonald, Angus; Macdonald, Archibald (1900). The Clan Donald. Vol. 2. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company, Ltd.

- Macdonald, Angus; Macdonald, Archibald (1900). The Clan Donald. Vol. 3. Inverness: The Northern Counties Publishing Company, Ltd.

- Maclauchlan, Thomas; Wilson, John (1875). Keltie, John Scott (ed.). A History of the Scottish Highlands, Highland Clans and Highland Regiments. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: A. Fullarton & Co.

- Newton, Norman S (2007). Skye. Edinburgh: David & Charles. ISBN 978-0-7153-2887-3.

- Richards, Eric (1982). A History of the Highland Clearances: Agrarian Transformation and the Evictions 1746–1886 (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0-7099-2249-3.

- Richards, Eric (2007). Debating the Highland Clearances. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-2182-8.

- Roberts, John Leonard (1999). Feuds, Forays and Rebellions: History of the Highland Clans, 1475–1625 (illustrated ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-6244-8.

- Roberts, John Leonard (2000). Clan, King, and Covenant (illustrated ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1393-5.

- Stewart, Donald Calder; Thompson, J. Charles (1980). Scarlett, James (ed.). Scotland's Forged Tartans. Edinburgh: Paul Harris Publishing. ISBN 0-904505-67-7.

- Way, George; Squire, Romilly (2000). Clans & Tartans. Glasgow: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-472501-8.

- Woolf, Alex (2007). From Pictland to Alba, 789–1070. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1233-8.

.png.webp)