Clare Winger Harris

Clare Winger Harris (January 18, 1891 – October 26, 1968[1]) was an early science fiction writer whose short stories were published during the 1920s. She is credited as the first woman to publish stories under her own name in science fiction magazines.[2][3] Her stories often dealt with characters on the "borders of humanity" such as cyborgs.[4]

Clare Winger Harris | |

|---|---|

Clare Winger Harris, as pictured in the 1929 debut issue of Science Wonder Quarterly | |

| Born | Clare Winger January 18, 1891 Freeport, Illinois |

| Died | October 26, 1968 (age 77) Pasadena, California |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1923–1930 |

| Genre | Science fiction |

| Spouse | Frank Clyde Harris |

| Children | 3 |

Harris began publishing magazine stories in 1926, and soon became well liked by readers. She published a total of twelve stories, all but one of which were collected in 1947 as Away From the Here and Now; a full collection was not published until 2019, in The Artificial Man and Other Stories. Her gender was a surprise to Hugo Gernsback, the editor who eventually bought most of her work, as she was the first American woman to publish in science fiction magazines under her own name.[1] Her stories, which often feature strong female characters, have been occasionally reprinted and have received some positive critical response, including a recognition of her pioneering role as a woman writer in a male-dominated field.

Life

Clare Winger was born on January 18, 1891, in Freeport, Illinois[5] and later attended Smith College in Massachusetts. Her father, Frank Stover Winger, was an electrical engineer who also had an interest in science-fiction writing; in 1917, he published a novel called The Wizard of the Island; or, The Vindication of Prof. Waldinger. Her mother, May Stover, was the daughter of D.C. Stover, founder of the Stover Manufacturing and Engine Company. (Frank was also related to the Stover family on his mother's side, hence his middle name.) Unusually for the era, after their children were born and raised, Frank and May divorced.

In 1912, Clare married Frank Clyde Harris.[6] Her husband was an architect and engineer who served in World War I and was chief engineer with the Loudon Machinery Company in Iowa and one of the organizers of the American Monorail Company of Cleveland, Ohio.[7]

Harris gave birth to three sons (Clyde Winger, born 1915; Donald Stover, born 1916; and Lynn Thackrey, born 1918).[6][7] She and her family lived in Iowa in 1925 according to a state census; sometime before 1930, the family moved to Lakewood, Ohio. Her career as a writer spanned the years 1923 to 1933, during her tenures in both these locations.

Harris ceased writing stories after 1933. She was still living in Lakewood in 1935, and according to an interview with her grandson, she and Frank "stayed together until their kids were fully grown."[8] Clare and Frank's youngest son turned 18 in 1936, and by 1940, U.S. census records show Clare W. Harris as divorced and living in Pasadena, California, where she lived the rest of her life. She privately published a collection of her stories in 1947, but otherwise little is known of the final decades of her life. She died on October 26, 1968, in Pasadena.[1]

Writing career

Harris debuted as a writer in 1923 with a novel, a piece of historical fiction entitled Persephone of Eleusis: A Romance of Ancient Greece. The rest of her work would be very different, as it consisted entirely of short stories in the realm of science fiction.

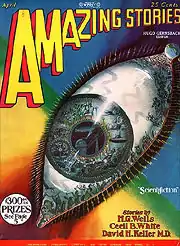

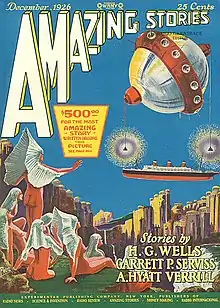

Harris published her first short story, "A Runaway World," in the July 1926 issue of Weird Tales.[9] In December of that year, she submitted a story for a contest being run by Amazing Stories editor Hugo Gernsback. Harris's story, "The Fate of the Poseidonia" (a space opera about Martians who steal earth's water),[2] placed third.[10] She soon became one of Gernsback's most popular writers.

Harris eventually published 11 short stories in pulp magazines, most of them in Amazing Stories (although she also published in other places such as Science Wonder Quarterly). She wrote her most acclaimed works during the 1920s; in 1930, she stopped writing to raise and educate her children.[3][11] Her absence from the pulps was noted—a fan wrote in to Amazing Stories in late 1930 to ask, “What happened to Clare Winger Harris? I’ve missed her . . .”[1] However, she did publish one story in 1933—titled "The Vibrometer," it appeared in a mimeographed pamphlet called Science Fiction. The editors, Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, were high school students in Cleveland at the time.[1][12]

In 1947, all of Harris's short stories except "The Vibrometer" were collected under the title Away from the Here and Now; a 2019 collection, The Artificial Man and Other Stories, also includes "The Vibrometer."[12] Her stories have also been reprinted in anthologies such as Daughters of Earth: Feminist Science Fiction in the 20th Century (with a critical essay), Sci-Fi Womanthology, Amazing Science Fiction Anthology: The Wonder Years 1926-1935, and Gosh Wow! Sense of Wonder Science Fiction.

Harris also wrote one of the first attempts to classify science fiction when, in the August 1931 issue of Wonder Stories, she listed 16 basic science fiction themes, including "interplanetary space travel," "adventures on other worlds," and "the creation of synthetic life."[13]

Critical view and influence

When Gernsback published Harris's first short story in Amazing Stories, he praised her writing while also expressing amazement that a woman could write good science fiction: "That the third prize winner should prove to be a woman was one of the surprises of the contest, for, as a rule, women do not make good scientifiction writers, because their education and general tendencies on scientific matters are usually limited. But the exception, as usual, proves the rule, the exception in this case being extraordinarily impressive."[10][14] For many years Harris claimed to have been the first woman science-fiction writer in the United States,[11] although later research proved this to be untrue, as Gertrude Barrows Bennett, writing under the pseudonym Francis Stevens, was publishing science fiction stories as early as 1917. Note that the true identity of "Francis Stevens" was not known publicly until 1952, long after the writing careers of both Harris and Bennett were over.

More recently, Harris is often credited with the narrower distinction of being the first American woman to publish stories in science fiction magazines under her own name.[4][11] Nevertheless, this must be qualified as well: as a teenager, Bennett, born Gertrude Mabel Barrows, published one story as G.M. Barrows (i.e., her own name) in a 1904 edition of Argosy magazine. Argosy, however, was not strictly speaking a science fiction magazine, as it ran stories from a number of genres.

Even though Harris published only a handful of stories, almost all of them have been reprinted over the years. Of these, "The Miracle of the Lily" has been reprinted the most and praised by many critics, with Richard Lupoff saying the story would have "won the Hugo Award for best short story, if the award had existed then."[15][16] Lupoff also wrote that "[w]hile today's reader may find her prose creaky and old-fashioned, the stories positively teem with still-fresh and provocative ideas.[17]

"The Fate of the Poseidonia" has also been reprinted a number of times and is credited as an early example of a science fiction story with a heroic female lead character.[18] Other of Harris's stories are also noted for featuring strong female characters, such as Sylvia, the airplane pilot and mechanic in "The Ape Cycle" (1930). Harris also wrote one story utilizing a female point of view (in 1928's "The Fifth Dimension").

Because Harris was the first American woman published in science fiction magazines under her own name, and because of her embrace of female characters and themes, she has been recognized in recent years as a pioneer of women's and feminist science fiction.[14]

Her work was featured at the Pasadena History Museum in 2018, as part of an exhibit titled "Dreaming the Universe: The Intersection of Science, Fiction, & Southern California."[19]

Bibliography

Novels

Collections

- Away from the Here and Now: Stories in Pseudo-Science (Philadelphia: Dorrance, 1947)

- The Artificial Man and Other Stories (Belt Publishing, February 2019)

Short stories

(Stories included in Away from the Here and Now).

- "A Runaway World" (Weird Tales, July 1926)

- "The Fate of the Poseidonia" (Amazing Stories, June 1927)[10]

- "A Certain Soldier" (Weird Tales, November 1927)

- "The Fifth Dimension" (Amazing Stories, December 1928)

- "The Menace From Mars" (Amazing Stories, October 1928)

- "The Miracle of the Lily" (Amazing Stories, April 1928)[16]

- "The Artificial Man" (Science Wonder Quarterly, Fall 1929)

- "A Baby on Neptune" with Miles J. Breuer, M.D. (Amazing Stories, December 1929)

- "The Diabolical Drug" (Amazing Stories, May 1929)

- "The Evolutionary Monstrosity" (Amazing Stories Quarterly, Winter 1929)

- "The Ape Cycle" (Science Wonder Quarterly, Spring 1930)

(Included in The Artificial Man and Other Stories).

- "The Vibrometer" (Science Fiction #5, 1933, edited by Jerry Siegel)[20]

Essays

- Letter (Amazing Stories, May 1929): A Very Interesting Letter from One of Our Authors

- Letter (Air Wonder Stories, September 1929) [only as by Clare W. Harris]: On why Air Wonder Stories may not make a good venue for her fiction

- Letter (Weird Tales, March 1930): Expression of appreciation for the style of Henry de Vere Stacpoole's The Blue Lagoon (novel)

- Letter (Wonder Stories, August 1931): Possible Science Fiction Plots

References

- "Meet the Reclusive Woman Who Became a Pioneer of Science Fiction". Literary Hub. 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- Donawerth, Jane (1990). "Teaching Science Fiction by Women". The English Journal (subscription required). 79 (3): 39–46. doi:10.2307/819233. JSTOR 819233.

- Davis, Cynthia J.; West, Kathryn (1996). Women Writers in the United States: A Timeline of Literary, Cultural, and Social History. Oxford University Press. p. 229. ISBN 978-0-19-509053-6.

- John Chute, Peter Nicholls, ed. (1993). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. St. Martin's Press. p. 544. ISBN 978-0-312-13486-0.

- Social Security Death Record for Clare Winger Harris, SS# 550-34-7527, accessed April 2, 2007.

- "Clare Winger Harris" (in German). www.feministische-sf.de. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- James Harris-Mary Cherry Family, PART 3, POSTERITY CHAPTER VI, Isaiah M. Harris-Wilkerson-Murrell Descendants, accessed April 2, 2007.

- "Meet the Reclusive Woman Who Became a Pioneer of Science Fiction". 27 March 2019.

- "Title: A Runaway World".

- Harris, Clare Winger (June 1927). "The Fate of the Poseidonia". Amazing Stories. pp. 245–252, 267.

- "Curiosities by Richard A. Lupoff". Fantasy and Science Fiction Magazine. 1998. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-03-30.

- "The Artificial Man and Other Stories by Clare Winger Harris". tangentonline.com. Archived from the original on 2019-03-31. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- Letter/essay from Clare Winger Harris, Wonder Stories, August 1931. An excerpt of this letter is reprinted on Google Groups here, accessed March 30, 2007.

- Justine Larbalestier, ed. (2006). "Introduction to Clare Winger Harris's "The Fate of the Poiseidonia"". Daughters of Earth: Feminist Science Fiction in the Twentieth Century. Wesleyan University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-8195-6676-8.

- "Science Fiction Timelines, 1920-30". Magic Dragon Multimedia. Retrieved 2007-03-30.

- Harris, Clare Winger (April 1928). "The Miracle of the Lily". Amazing Stories. pp. 48–55.

- "Curiosities, F&SF, July 1998

- Donawerth, Jane (2006). "Illicit Reproduction: Clare Winger Harris's 'The Fate of the Poiseidonia'". In Justine Larbalestier (ed.). Daughters of Earth: Feminist Science Fiction in the Twentieth Century. Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6676-8.

- "Pasadena History Museum • Dreaming the Universe". Pasadena Museum of History. Archived from the original on 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2019-03-27.

- Moskowitz, Sam (June 1958). "How "Superman" Was Born". Future Science Fiction. 37: 122 – via Internet Archive.

Further reading

- Yaszek, Lisa, et al. Sisters of Tomorrow: The First Women of Science Fiction, Wesleyan University Press, 2016, pp. 8–9. Google Books.

External links

- Works by Clare Winger Harris at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Clare Winger Harris at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Clare Winger Harris at Internet Archive

- Clare Winger Harris at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Amazing Stories archive at The Online Books Page

- Bibliography at The FictionMags Index