Clemuel Ricketts Mansion

The Clemuel Ricketts Mansion (also known as the Stone House, the William R. Ricketts House, and Ganoga) is a Georgian-style house made of sandstone, built in 1852 or 1855 on the shore of Ganoga Lake in Colley Township, Sullivan County, Pennsylvania in the United States. It was home to several generations of the Ricketts family, including R. Bruce Ricketts and William Reynolds Ricketts. Originally built as a hunting lodge, it was also a tavern and post office, and served as part of a hotel for much of the 19th century.

Clemuel Ricketts Mansion | |

The front of the mansion, with the 1913 addition at left | |

| |

| Location | Colley Township, Sullivan County, Pennsylvania |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°21′8″N 76°19′14″W |

| Area | 2.2 acres (0.89 ha) |

| Built | 1852 or 1855 |

| Architect | Clemuel Ricketts |

| Architectural style | Georgian |

| NRHP reference No. | 83002284[1] |

| Added to NRHP | June 9, 1983 |

After 1903 the house served as the Ricketts family's summer home; they kept it even as they sold over 65,000 acres (26,000 ha) to the state of Pennsylvania from 1920 to 1950. The house was included in the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) in 1936 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in 1983. A group of investors bought the lake, surrounding land, and house in 1957 and developed them privately for housing and recreation. The house became the Ganoga Lake Association's clubhouse, and is not open to the public.

The original mansion is an L-shaped structure, two-and-a-half stories high, with stone walls 2 feet (0.6 m) thick. It was built in a clearing surrounded by old-growth forest with a view to the lake 900 feet (270 m) to the east. In 1913 a 2+1⁄2-story wing was added to the north side of the house and the original structure was renovated. The house has seven rooms, four porches, and its original hardware and woodwork. Dormers and some windows were added in the renovation, and electrical wiring and modern plumbing have been added since. According to the NRHP nomination form, the Clemuel Ricketts Mansion "is a stunning example of Georgian vernacular architecture".[2]

Location

The Clemuel Ricketts Mansion is on the southwest shore of Ganoga Lake in Colley Township in the southeastern part of Sullivan County. The mansion and lake are on a part of the Allegheny Plateau known as North Mountain; the plateau formed about 300 to 250 million years ago in the Alleghenian orogeny. Rocks—gray sandstone with conglomerates and some siltstone—of the Mississippian Pocono Formation more than 340 million years old, underlie the house and lake.[3] The lake is in a shallow valley, 13 feet (4.0 m) deep, which is impounded by glacial till up to 30 feet (9.1 m) thick at the southeast end, where Kitchen Creek exits.[4]

The earliest recorded inhabitants of the region were the Susquehannocks, who left or died out by 1675. The land then came under the control of the Iroquois, who sold it to the British in the Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768.[5] The land on which the house was later built was first part of Northumberland County, then became part of Lycoming County in 1795.[6] The Susquehanna and Tioga Turnpike, which followed the lake's western shore, was built between 1822 and 1827; it connected the Pennsylvania communities of Berwick in the south and Towanda in the north. The lake was then known as Long Pond, and the Long Pond Tavern, just north of where the house was later built, was a lunch stop for the stagecoach on the turnpike.[7][8][9] Sullivan County was formed from Lycoming County in 1847, and two years later Colley Township was formed from Cherry Township.[10]

History

Lodge and tavern

Brothers Clemuel Ricketts (1794–1858) and Elijah G. Ricketts (1803–1877) were frustrated at having to spend the night on a hotel's parlor floor while on a hunting trip on Loyalsock Creek north of Ganoga Lake in 1850, and wanted their own hunting preserve. They bought the lake, Long Pond Tavern, and 5,000 acres (2,000 ha) of surrounding land in the early 1850s and soon began building a stone house between the turnpike and the lake shore to replace the log tavern. According to William Reynolds Ricketts' HABS history of the house,[7] Petrillo's history of the region Ghost Towns of North Mountain,[8] and the house's NRHP nomination form,[2] the Ricketts brothers bought the lake and surrounding land in 1851, began building the stone house that year, and finished it in 1852. The year 1852 is also carved in stone on the front (west side) of the house, which faced the highway.[11] However, according to Tomasak's The Life and Times of Robert Bruce Ricketts, the brothers purchased the lake, tavern, and land on April 13, 1853, for $550 (approximately $19,000 in 2023), and had the house built from 1854 to 1855.[12][13]

According to Ricketts family tradition, Gad Seward built the mansion. While it was originally known as "Ricketts Folly" for its isolated location in the wilderness, the official name was the Stone House. The house served as the brothers' lodge and as a tavern for travelers on the turnpike. Clemuel was named postmaster of a new post office at the lake on October 3, 1853, and received a tavern license from Sullivan County on August 7, 1854. When Clemuel died in 1858, Elijah bought his share of the house and land. The post office closed April 12, 1860.[7][8][14]

Elijah's son Robert Bruce Ricketts (1839–1918), for whom the nearby Ricketts Glen State Park is named, joined the Union Army as a private at the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861, and rose through the ranks to become a colonel in the artillery. After the war, R. B. Ricketts returned to Pennsylvania and purchased the stone house, lake, and some of the land around it from his father on September 25, 1869, for $3,969.81 (approximately $87,000 in 2023); eventually he controlled or owned more than 80,000 acres (32,000 ha), including the lake and the park's glens and waterfalls.[7][13][15][16][17]

From 1872 to 1875 Ricketts and his partners operated a sawmill 0.5 miles (0.8 km) southeast of his house. In 1872 Ricketts used lumber from the mill to build a three-story wooden addition about 100 feet (30 m) north of the stone house, with a verandah connecting the two. The addition cost $45,000 (approximately $1,099,000 in 2023), and was known as the Ark for its resemblance to Noah's Ark. That same year Ricketts put new white birch floors in the stone house, which are still there as of 2008.[7][8][18][19]

Hotel

The Ark and stone house together formed the North Mountain House hotel, which opened in 1873, and was managed by Ricketts' brother Frank until 1898. Many of the guests, who came from Wilkes-Barre, Philadelphia, New York City, and other places, were Ricketts' friends and relations. The hotel was open year-round; in summer, guests frequently arrived after school let out in June and stayed until school resumed in September. In 1876 and 1877, Ricketts ran the first summer school in the United States at his house and hotel; one of the teachers was Joseph Rothrock, later known as the "Father of Forestry" in Pennsylvania.[7][8][18][19]

By 1874 Ricketts had renamed Long Pond as Highland Lake,[20] and by 1875 had named the highest waterfall on Kitchen Creek as Ganoga Falls.[21][22] That year the North Mountain House hotel was featured in John B. Bachelder's travel guide Popular resorts, and how to reach them, which praised its location in a virgin forest, the lake and nearby waterfalls, and opportunities for hunting, fishing, and hiking.[23] In 1881, Ricketts renamed Highland Lake as Ganoga Lake. Pennsylvania senator Charles R. Buckalew suggested the name Ganoga, an Iroquoian word which he said meant "water on the mountain" in the Seneca language.[7][8]

The house and hotel were on the east side of the old turnpike; a 100-acre (40 ha) field on the other side of the road had a small herd of milk cows and a vegetable garden to provide for the guests' needs. The field also had a rifle range and a nine-hole golf course. Guests could enjoy tennis and croquet, and a lawn stretched from the house east to the lake, which offered boating and bathing. There was an outlook point 0.5 miles (0.8 km) southwest of the house, and Ricketts built a 40-foot (12 m) observation tower at the highest point on North Mountain, 3.5 miles (5.6 km) south. After the first tower collapsed, he built a 100-foot (30 m) replacement, and named the site Grand View.[24]

Ricketts was a lumberman who made his fortune clearcutting nearly all his land, but no logging was allowed within 0.5-mile (0.8 km) of the lake,[25] and the glens and their waterfalls in the state park were "saved from the lumberman's axe through the foresight of the Ricketts family".[26] One hemlock tree cut near the lake to clear land for a building in 1893 was 6 feet (1.8 m) in diameter and 532 years old.[25] The North Mountain House hotel was threatened by a forest fire in 1900; the subsequent loss of much of the surrounding old-growth forest led to decreased numbers of hotel guests. Changing tastes may have also played a role in the decline in popularity; the hotel had over 150 guests in August 1878, but only about 70 guests in August 1894.[27]

In 1903 another large fire on North Mountain threatened the sawmill in the lumber town of Ricketts northeast of the lake. Beginning in 1893, a 3.85-mile (6.20 km) branch line of the Lehigh Valley Railroad ran from Ricketts to a log station at the north end of the lake; a boardwalk and coach service brought guests from the station to the hotel. There was daily passenger service to Wilkes-Barre and Towanda, and the line also served freight trains hauling ice from the lake for use in refrigeration from 1895.[7][8][28]

The North Mountain House was long known for its rustic charms; it was heated with open fireplaces, decorated with animal skins and hatracks made of antlers, and had two live black bears on chains in the field across the road from the house. In 1895 and 1900 the stone house was refurbished, and telephone service, acetylene lighting, and steam heat were added.[29] In 1900 The Sullivan Review newspaper recalled its former state and wrote of the changes: "We hardly call that an improvement. ... When the North Mountain House is lighted by gas, heated by a modern furnace, etc., its great charm is gone."[30]

House

The wooden addition to the stone house was torn down in either 1897 or 1903, and the land became a garden.[a] The hotel closed in November 1903, and passenger train service ended at that time. The sawmills at Ricketts closed when the timber was exhausted in 1913, and the ice company closed in 1915.[7][31] The stone house remained the Ricketts' summer home. Ricketts proposed moving the highway from his front yard in 1904; the Pennsylvania General Assembly approved this in 1908, after he paid for the construction of the new highway, 1.5 miles (2.4 km) east of the house. Thomas Henry Atherton of Wilkes-Barre was the architect for a new wing that was added to the stone house in 1913, as well as renovations to the original structure. Ricketts died in 1918 at the stone house; his wife died a few days after and they are buried in the small Ricketts family cemetery near the north end of the lake.[7][8][32] As part of Ricketts' will, the stone house and its outbuildings were valued at $12,000 in 1918 (approximately $233,000 in 2023).[13][33]

R. B. Ricketts and his wife had three children; their son William Reynolds Ricketts (1869–1956) lived in the house after his parents' deaths. Beginning in 1920, the Ricketts heirs began selling land to the state of Pennsylvania, but still owned over 12,000 acres (4,900 ha) surrounding the house, Ganoga Lake, and the glens with their waterfalls. The stone house was included in the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) in 1936 as the William R. Ricketts House. Atherton, the architect for the 1913 addition, helped prepare the HABS architectural drawings, which gave the house's name as "Ganoga". William Reynolds Ricketts' history for the HABS refers to it as the stone house.[7][34] The area was approved as a national park site in the 1930s; a 1935 article in The New York Times reported that the federal government planned to purchase 22,000 acres (8,900 ha) in the area, mentioning the waterfalls and the Ricketts estate and house, which it called "the oldest stone hotel in Pennsylvania".[16][35] The National Park Service operated a Civilian Conservation Corps camp at "Ricketts Glynn" (sic),[36][37] but budget problems and World War II brought an end to national plans for development.[16][38]

In 1942 the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania began buying the glens and their waterfalls from the heirs for $82,000 (approximately $1,469,000 in 2023)[13] and opened Ricketts Glen State Park in 1944; from 1920 to 1950 the state bought more than 65,000 acres (26,000 ha) from the Ricketts family for the park and Pennsylvania State Game Lands.[16][39] William Reynolds Ricketts died in 1956 and the lake and surrounding land were sold in October 1957 for $109,000 (approximately $1,136,000 in 2023).[13] The Department of Forests and Waters (predecessor of the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources) bid on the 3,140 acres (1,270 ha) including the house and lake, but were outbid by a group of private investors. These "formed the Lake Ganoga Association in September 1959 to regulate and preserve the recreation and residential facilities at Lake Ganoga".[40] The association built a road around the lake, cleared some land at its southern end, and its members built about 50 houses on the lake shore. In 1983 the stone house was listed on the National Register of Historic Places as the Clemuel Ricketts Mansion;[2] it serves as the association's headquarters and clubhouse, and is used for association meetings, weddings, and picnics.[41] As part of a private development, the house and lake are not open to the public:[42] "To all outsiders that have no property around the lake, the lake and grounds are off limits."[43]

Architecture

Clemuel Ricketts, the architect of the stone house, was very interested in architecture from the colonial period and had traveled widely. In the 1840s he published a book which examined the British and European sources of colonial architecture in the United States. Clemuel designed the house in the colonial or Georgian style in the early 1850s; construction began in either 1851 or 1854 and finished the next year.[2][7][12]

The Clemuel Ricketts Mansion lies 900 feet (270 m) west of Ganoga Lake, on what the HABS map described as a 2.2-acre (0.89 ha) "clearing completely surrounded by primeval forest", with a view to the lake.[7] The house was originally on the east side of the turnpike and faced it, but when what became Pennsylvania Route 487 was built in 1907, the course of the highway was changed so that it now runs on the other (east) side of the lake. Since then, the house is on a private road 1.5 miles (2.4 km) from the highway.[2][7][9]

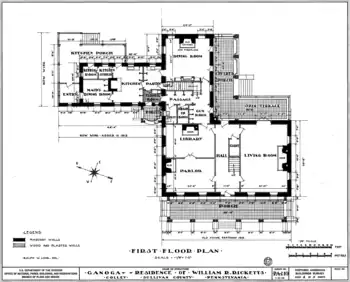

The original house built in the 1850s is L-shaped. According to the architectural drawings made for the HABS, the bottom of the L is 60 feet 4 inches (18.39 m) north–south by 35 feet 8 inches (10.87 m) east–west. In 1935 the ground floor of this part of the house included the main door and entrance hall, living room, parlor, library, and stairs. The main entrance is on the west side, which has a porch 60 feet 4 inches (18.39 m) wide by 12 feet (3.7 m) deep, supported by pairs of square pillars with stairs on the north, south, and west sides. The top of the L is 24 feet 2 inches (7.37 m) north–south by 40 feet 6 inches (12.34 m) east–west, and in 1935 the ground floor of the top of the L had the dining room, gun room, "brush up room", toilet, stairs, and a passage to the 1913 addition.[7] The inside corner of the L has a two-story covered porch along the south side, and an open terrace on the east side's ground floor. In 1935 the second story of the original house had four bedrooms and a bathroom in the lower part of the L and two bedrooms and a bath in the upper part, as well as two staircases and hallways.[2][7]

The mansion's stone walls are 2 feet (0.6 m) thick; the individual building stones are "field sandstone about 17 inches square, of various thicknesses" (17 inches is 43 cm).[7] There is a basement below the original house. The lower part of the L is five bays by two bays; the original double-hung sash windows in each bay of the 1850s house have six panes of glass per sash. All the original windows have shutters, these are paneled on the first floor and louvered on the second. The main door is in the Federal style with a large fanlight above the door and sidelights on either side. The attic in the 1850s part of the house is not finished, and the gable roof has "boxed cornices with returns".[2][7]

In 1897 or 1903 a formal garden was added north of the stone house, on the site of the razed wooden structure where most of the hotel guests had stayed.[7] In 1913 a two-and-half story wing was added on the north side of the original house, which was renovated; Thomas Henry Atherton was the architect. The new wing is 48 feet 3 inches (14.71 m) north–south and 20 feet 4 inches (6.20 m) east–west, with a large enclosed one-story porch on the north and east sides. In 1935 the addition had the kitchen, pantry, storage and refrigeration rooms, and a "maid's dining room" on the first floor,[7] two bedrooms and a bathroom on the second floor, and two servant rooms and a bath in the finished attic.[2][7]

The new wing has six dormers (three on a side), and six dormers were added to the old house in the 1913 renovation (four on the east side, two on the west). The windows on the first floor of the new wing matched the old windows, but the windows in the second story of the addition have twelve panes in the upper sash and eight in the lower. As part of the renovation work, four new windows were placed in the 1850s house: two just west of the new wing, and two on the east wall of the lower part of the L. A small porch was added in the corner where the west wall of the new wing meets the north wall of the old house, and all the old porches were restored. In the original house two chimneys were restored and two replaced, and new fireplaces were installed in the living room, library, and dining room. The house has a total of 28 rooms.[2][7]

The NRHP nomination form lists two other structures on the property: a utility building made of brick and covered in stucco east of the house,[b] and a large barn to the southwest. Since the house's 1913 renovation, the only changes have been the installation of electrical wiring and modernization of the plumbing. The original hardware and woodwork are still present inside the house. According to the NRHP nomination form, the Clemuel Ricketts Mansion "is a stunning example of Georgian vernacular architecture" which "represents the manifestations of one man's architectural dream preserved within the wilderness for over a century".[2]

Notes

- a. ^ All sources agree that the North Mountain House hotel closed in 1903, but differ on the date that the wooden addition used for the hotel was torn down. William Reynold's Ricketts' history for the HABS and Petrillo's book both report it was razed in 1897,[7][8] while McDonald's NRHP nomination form and Tomasak's book give the year as 1903.[2][32]

- b. ^ According to Tomasak's book, this utility building served as William Reynolds Ricketts library, and was where he worked on his stamp collection. Later, it served as the office from which the Ganoga Lake Association sold lots around the lake. Follow these links for photographs of the utility building and of the barn.[41]

References

- "NPS Focus: Search page". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. Archived from the original (Enter: Ricketts, Clemuel, Mansion) on July 25, 2008. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- McDonald, pp. 1–6.

- Braun, Inners, pp. 1–13.

- Braun, p. 12.

- Wallace, pp. 99–108, 159.

- "Lycoming County 5th class" (PDF). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- Ricketts, pp. 2–6.

- Petrillo, pp. 40–43.

- Wilson, Jr., Kenneth T. (Spring 1990). "Sketches from the Susquehanna-Tioga Turnpike". Carver Magazine. 8 (1). Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- "Sullivan County 7th class" (PDF). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Retrieved April 12, 2010.

- See this photograph of the date 1852 carved on the front of the house.

- Tomasak, p. 38.

- "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2008". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Archived from the original on December 20, 2014. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- Tomasak, pp. 38–40.

- Petrillo, pp. 40, 77.

- "Ricketts Glen State Park". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on February 2, 2004. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- "Ricketts Glen Project Sidetracked". Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin. February 28, 1936. Retrieved July 1, 2010.

- "History of the Rothrock State Forest". Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on March 2, 2004. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- Tomasak, pp. 83, 323.

- Tomasak, p. 98.

- Bachelder, pp. 186–189.

- Tomasak, p. 85.

- Bachelder, pp. 184–192.

- Tomasak, pp. 100, 323, 327.

- Petrillo, pp. 50–55.

- "50,000 will see Rickett's Glen Charms". Williamsport Sun. September 4, 1947. p. 12.

- Tomasak, pp. 88, 323, 326, 328–329.

- Tomasak, pp. 324, 328–329.

- Tomasak, pp. 313–314, 324, 327–328.

- The Sullivan Review, November 1, 1900, quoted in Tomasak, p. 328.

- Petrillo, pp. 1, 50, 53, 55

- Tomasak, p. 313.

- Tomasak, p. 398.

- Tomasak, p. 332.

- "Plans Pennsylvania Park". The New York Times. March 30, 1935. p. 17.

- "Camp Information for SP-9-PA". Pennsylvania CCC Archive. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- Paige, John C. (1985). "Appendix C, Table C-1: Directory of CCC Camps Supervised by the NPS (updated to December 31, 1941).". The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933–1942: An Administrative History. National Park Service, Department of the Interior. OCLC 12072830.

- "Ricketts Glen Project Sidetracked". Williamsport Gazette and Bulletin. February 28, 1936. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- Petrillo, p. 69.

- Petrillo, pp. 68–70.

- Tomasak, pp. 376–377.

- Lamey-Welshans, Jessica (October 26, 2008). "Ghost town of Ricketts brought back to life by state park educator". Williamsport Sun-Gazette. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- Tomasak, p. 376.

Works cited

- Bachelder, John B. (1875). Popular resorts, and how to reach them. Combining a Brief Description of the Principal Summer Retreats in the United States, and the Routes of travel Leading to Them. Boston, Massachusetts: J. B. Bachelder Publishing. OCLC 317328980.

- Braun, Duane D. (2007). "Surficial geology of the Red Rock 7.5-minute quadrangle, Luzerne, Sullivan, and Columbia Counties, Pennsylvania" (PDF). Pennsylvania Geological Survey, 4th series, Open-File Report OFSM 07-10.0. Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2012. Retrieved May 15, 2010.

- Braun, Duane D.; Inners, Jon D. "Pennsylvania Trail of Geology, Ricketts Glen State Park, Luzerne, Sullivan and Columbia Counties, The Rocks, the Glens and the Falls (Park Guide 13)" (PDF). Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 20, 2004. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

- McDonald, Teresa B. (1980). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Clemuel Ricketts Mansion" (PDF). Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- Petrillo, F. Charles (1991). Ghost Towns of North Mountain: Ricketts, Mountain Springs, Stull (PDF). Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: Wyoming Historical & Geological Society. ISBN 978-0-937537-00-8. OCLC 25080093. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 27, 2009. Retrieved April 11, 2010.

- Ricketts, William Reynolds (1936). "William R. Ricketts House, North Mountain Colley, Ganoga Lake, Sullivan County, PA". Historic American Buildings Survey. Library of Congress. Retrieved April 11, 2010. Note: The map and architectural drawings included are also used as references in this article.

- Tomasak, Peter (2008). In Command of Time Elapsed: The Life and Times of Robert Bruce Ricketts. Kyttle, Pennsylvania: North Mountain Publishing Company.

- Wallace, Paul A. W.; Hunter, William A. Hunter (2005). Indians in Pennsylvania (Second ed.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. ISBN 9781422314937. OCLC 1744740. Retrieved April 11, 2010. (Note: OCLC refers to the 1961 first edition.)

External links

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. PA-210, "William R. Ricketts House, North Mountain Colley, Colley, Sullivan County, PA", 3 photos, 6 measured drawings, 5 data pages