The Clerk's Tale

"The Clerk's Tale" is the first tale of Group E (Fragment IV) in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales. It is preceded by The Summoner's Tale and followed by The Merchant's Tale. The Clerk of Oxenford (modern Oxford) is a student of what would nowadays be considered philosophy or theology. He tells the tale of Griselda, a young woman whose husband tests her loyalty in a series of cruel torments that recall the biblical Book of Job.

Plot

The Clerk's tale is about a marquis of Saluzzo in Piedmont in Italy named Walter, a bachelor who is asked by his subjects to marry to provide an heir. He assents and decides he will marry a peasant, named Griselda. Griselda is a poor girl, used to a life of pain and labour, who promises to honour Walter's wishes in all things.

After Griselda has borne him a daughter, Walter decides to test her loyalty. He sends an officer to take the baby, pretending it will be killed, but actually conveying it in secret to Bologna. Griselda, because of her promise, makes no protest at this but only asks that the child be buried properly. When she bears a son several years later, Walter again has him taken from her under identical circumstances.

Finally, Walter determines one last test. He has a papal bull of annulment forged which enables him to leave Griselda, and informs her that he intends to remarry. As part of his deception, he employs Griselda to prepare the wedding for his new bride. Meanwhile, he has brought the children from Bologna, and he presents his daughter as his intended wife. Eventually, he informs Griselda of the deceit, who is overcome by joy at seeing her children alive, and they live happily ever after.

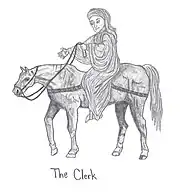

Narrator

The tale is told by the Clerk of Oxford, who is a scholar of logic and philosophy. In the General Prologue, he is described as thin and impoverished, hard-working and wholly dedicated to his studies:

Yet hadde he but litel gold in cofre;

- But al that he myghte of his freendes hente,

- On bookes and on lernynge he it spente.

The Clerk claims that he heard the tale from Petrarch in Padua.[1]

Sources

The story of patient Griselda first appeared as the last chapter of Boccaccio's Decameron, and it is unclear what lesson the author wanted to convey. Critics suggest Boccaccio was simply putting down elements from the oral tradition, notably the popular topos of the ordeal, but the text was open enough to allow very misogynistic interpretations, giving Griselda's passivity as the norm for wifely conduct.[2]

In 1374, it was translated into Latin by Petrarch, who quotes the heroine, Griselda, as an exemplum of that most feminine of virtues, constancy.[2] Circa 1382–1389, Philippe de Mézières translated Petrarch's Latin text into French, adding a prologue which describes Griselda as an allegory of the Christian soul's unquestioning love for Jesus Christ.[2] As far as Chaucer is concerned, critics think he used both Petrarch's and de Mézières's texts, while managing to recapture Boccaccio's opaque irony.[2] Anne Middleton is one of many scholars to discuss the relationship between Petrarch's original and Chaucer's reworking of the tale.[3]

Footnotes

- The Clerks Prologue, 26–32

- The reception of Boccaccio's Griselda (French text) Archived 2 September 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Middleton, Anne (1980). "The Clerk and his Tale: Some Literary Contexts". Studies in the Age of Chaucer. 2: 121–50. doi:10.1353/sac.1980.0006. S2CID 165954387. Middleton's article is discussed in, for instance, Galloway, Andrew (2013). "Petrarch's Pleasures, Chaucer's Revulsions, and the Aesthetics of Renunciation in Late-Medieval Culture". In Frank Grady (ed.). Answerable Style: The Idea of the Literary in Medieval England. Interventions: New Studies in Medieval Culture. Andrew Galloway. Ohio State University Press. pp. 140–66. ISBN 9780814212073.

.jpg.webp)