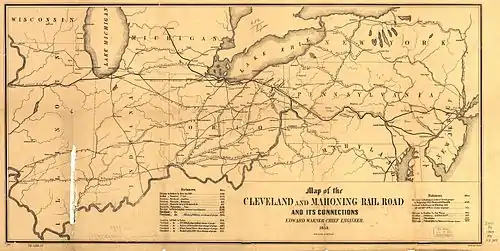

Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad

The Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad (C&MV) was a shortline railroad operating in the state of Ohio in the United States. Originally known as the Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad (C&M), it was chartered in 1848. Construction of the line began in 1853 and was completed in 1857. After an 1872 merger with two small railroads, the corporate name was changed to "Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad". The railroad leased itself to the Atlantic and Great Western Railway in 1863. The C&MV suffered financial instability, and in 1880 its stock was sold to a company based in London in the United Kingdom. A series of leases and ownership changes left the C&MV in the hands of the Erie Railroad in 1896. The CM&V's corporate identity ended in 1942 after the Erie Railroad completed purchasing the railroad's outstanding stock from the British investors.

Former Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad tracks in Cleveland, Ohio | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. |

| Dates of operation | February 22, 1848–December 22, 1941 |

| Successor | Erie Railroad |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge (post-1880) |

| Previous gauge | 4 ft 9+3⁄8 in (1,457 mm) (1856-1880) |

| Length | 67.81 miles (109.13 km) |

A number of ownership changes since 1942 have left the track in various corporate hands. Portions of the track are now biking and hiking trails.

Founding

Jacob Perkins, a prominent attorney in the city of Warren in Trumbull County, Ohio,[1] was the leader in the movement to build a railroad between Cleveland (a fast-growing industrial center and port on the shores of Lake Erie) and the coal fields of east-central Ohio.[2] A previous road to that area, the Ohio and Erie Railroad, was proposed earlier but nothing came of this project.[3] Perkins helped incorporate the Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad, which was chartered by the state of Ohio on February 22, 1848. It was authorized to build a rail line from Cleveland to an unspecified point near Warren.[4][5] Initially, Perkins attempted to interest the Ohio and Pennsylvania Railroad (O&P) into building the line, but that company declined. He then offered the charter to the Pittsburgh and Erie Railroad, but it was uninterested as well.[2]

The state reissued the charter, with minor amendments, on March 20, 1851.[4][6] One of these changes allowed the road to build its line into Pennsylvania, if that state permitted it.[7] The Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad was organized on September 20, 1851.[6][8] The incorporators included[9] Perkins; Dudley Baldwin, Cleveland investment banker;[10] Robert Cunningham, businessman in New Castle, Pennsylvania; Frederick Kinsman, a Trumbull County judge and land agent;[11] James Magee, a wealthy Philadelphia tack manufacturer and one of the founders of the Pennsylvania Railroad;[12] Charles Smith, a Warren businessman and banker;[13] and David Tod, Mahoning County attorney and former U.S. ambassador to Brazil.[14] The initial board of directors included[3] Perkins, Baldwin, Kinsman, Smith, Tod, and Reuben Hitchcock, a judge from Painesville in Lake County, Ohio.[15] Cleveland was chosen as the corporate headquarters.[2]

Route and route changes

Deciding on a route

The company surveyed a number of different routes.[2] The route proposed in 1851 had the railroad's northern terminus in Cleveland,[8] where it would connect with the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad.[6] The route then ran through Chagrin Falls, Garrettsville, Warren, Niles, Girard, Youngstown, Poland, and Petersburgh before terminating at Enon Valley, Pennsylvania.[8] Company officials decided in 1852 to bypass Youngstown entirely, shifting the route south (along what is now Interstate 76 and Interstate 80) to reach Enon Valley. David Tod, who returned to the United States from Brazil in 1852, was angry that the railroad would bypass the largest city in his county. He convinced company officials to change the route back.[16]

The railroad then proposed that, after leaving Youngstown, the route should follow the Mahoning River to New Castle.[6] There, it would connect with the North Western Railroad[6][17][18][lower-alpha 1] and the Ohio & Pennsylvania Railroad.[6][19][lower-alpha 2] The former gave it access to the Pennsylvania Railroad, while the latter provided access to the industrial and agricultural region between New Castle and New Brighton.[20]

At the end of December 1852, a new board of directors was elected.[19][21] Retained were Baldwin, Kinsman, Perkins, Smith, and Tod; newly elected were Charles L. Rhodes, former agent for the Cleveland and Pittsburgh Railroad,[22] and Henry Wick, a prominent Cleveland banker.[23] Perkins was elected president.[21]

Gauge and fundraising

As the company prepared for construction, it had to decide on a track width ("gauge"). The track width has been characterized as both narrow-gauge[18][24] and standard-gauge.[25][26][27][28] It was neither; the gauge was a highly unusual 4 feet 9.375 inches (1,457.32 mm).[29][30] At the time, nearly all railroads in Ohio were built with a 4-foot-10-inch (1,470 mm) gauge (the "Ohio gauge").[17] The directors of the new railroad chose the slightly narrower gauge because they believed it would allow the road to also haul standard-gauge railcars.[29] The confusion about the C&M's gauge likely stems from the fact that the Atlantic and Great Western Railway (a broad-gauge railway) and its owned and leased subsidiaries (which included the C&M) converted to standard-gauge on June 22, 1880.[31]

The Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad initially sold stock to raise construction funds. Investors in Warren and Youngstown bought $275,000 ($8,800,000 in 2022 dollars) in stock, while those in Cleveland purchased $100,000 ($3,500,000 in 2022 dollars).[19]

The route was surveyed by the end of 1852, and construction was ready to begin toward Warren from Cleveland.[19]

First phase of grading

Work on the track began in 1853.[4] The company said in January that it had identified locations in Cleveland for the construction of its freight and passenger stations and its docks on the Cuyahoga River. The company also altered its route and bypassed Chagrin Falls after residents there failed to purchase enough of the company's stock.[32][lower-alpha 3] The new route shifted south, passing through Mantua.[2][lower-alpha 4] Company officials also said the railroad would not go south to the village of Poland after passing through Youngstown, again due to a lack of stock subscription.[32] The railroad would instead follow the Mahoning River southeast to New Castle[35] and might even go as far south as New Brighton.[36]

Grading and track work in Cleveland in 1853 began at the Old Ship Channel of the Cuyahoga River in the Ohio City neighborhood of Cleveland. The route crossed the Old Ship Channel to land near Mulberry Avenue, headed southeast (paralleling the avenue), then ran along the Irishtown Bend of the Cuyahoga River. It cut overland to the southeast to avoid the Scranton Flats and Collision Bend[lower-alpha 5] and crossed to the east bank of the Cuyahoga just north of Kingsbury Run. The tracks then ran parallel to and east of Broadway Avenue, shifting to an east-southeast direction about E. 55th Street. After crossing the tracks of the Cleveland & Pittsburgh Railroad, the C&M turned sharply southward. Before reaching Hamilton Avenue (now called Harvard Avenue), the tracks shifted southeast again, largely paralleling Harvard Avenue, Caine Avenue, and Miles Avenue before leaving the city.[37] This work was completed by a company based in Livingston, New York. The C&M's "Western Division" ran from Cleveland to Warren. This section was graded by a company from Buffalo, New York.[38] The railroad's "Eastern Division" ran from Warren to its terminus. Grading here was completed by Britton & Co., a construction firm based in Warren.[39] Work between Warren and Youngstown began about August 1853.[40]

The road proved more costly to build than anticipated. To obtain more funds, the company sold $850,000 ($29,900,000 in 2022 dollars) in bonds on August 22, 1853.[41] Another $300,000 ($9,800,000 in 2022 dollars) in stock was sold in Philadelphia in early 1854.[42] By July, grading was complete in Cleveland from the Cuyahoga River to the top of the heights in what was then Newburgh Township.[43][lower-alpha 6] Once more, the railroad ran out of money. This time, it estimated it needed another $200,000 ($6,500,000 in 2022 dollars) to complete grading the road to Youngstown.[48]

Second phase of grading

To raise the necessary funds, the railroad decided to sell more bonds. The bond sales faltered badly due to the economic challenges brought about by the 1853–54 recession.[3][49] Perkins traveled to the United Kingdom in the spring of 1854 to try to sell bonds to investors there, but met with no success.[2] Perkins returned to the United States, where board members pleaded with him to take over the railroad's presidency in an effort to improve its reputation among investors. Perkins agreed to do so, and even pledged to put $100,000 ($3,300,000 in 2022 dollars) of his own money into the railroad—but only if his fellow board members agreed to personally guarantee the road's debts. The board members agreed to do so,[2][3][9] with their investment totaling $440,000 ($14,300,000 in 2022 dollars).[20] The strategy worked, for the company was able to sell another $469,200 ($15,300,000 in 2022 dollars)[20] in bonds on September 8, 1854.[41]

With construction tentatively scheduled for completion between Cleveland and Warren in 1855, Perkins and Tod spent two weeks in December 1954 in Philadelphia, where they managed to personally borrow $20,000 ($700,000 in 2022 dollars) which enabled the company to purchase two locomotives.[3][50] The road now had sufficient funds to buy rails to lay track from Cleveland to Youngstown and a limited quantity of rolling stock to begin operations.[50] Rails were purchased from the Phoenixville Manufacturing Co., and the first shipment arrived in late May 1855.[51] The railroad's first locomotive, the Philadelphia, was manufactured by the Cuyahoga Steam Furnace Co. and delivered in late July.[52] The second big shipment of rails arrived in mid-October.[53]

Opening of the line between Cleveland and Warren

At Plank Road Station, on Cleveland's southern border, the railroad constructed its first rail yard. The hamlet which grew up around the yards was renamed Randall, in honor of former United States Postmaster General Alexander Randall. (It was incorporated as the village of North Randall in 1908.)[54] Most of the route in Portage County, Ohio, was graded in 1855, and track partially laid. By November 7, the line was complete between Mantua and Warren, and construction trains were running on the line.[55] On November 20, the C&M awarded a contract to the Chamberlain Co. to grade the route from Youngstown to New Castle.[56]

The winter which began in late 1855 was extremely severe, and little construction could be accomplished. This pushed the date for completion of the line into 1856.[57] To accept freight directly from cargo ships, the railroad announced in March 1856 it would build docks on either side of Columbus Street on the south bank of the Cuyahoga River (the southernmost part of Irishtown Bend).[58] The first 30 miles (48 km) of track south of Cleveland opened in April 1856.[59] On July 1, the railroad opened all the way to Warren.[57][60]

With the beginning of rail operations, the C&M needed a superintendent to manage the road's day-to-day operations. W.C. Clelland, of the Pittsburg & Cleveland Railroad, was appointed superintendent on June 15, 1856,[61] but he resigned suddenly just a month later.[62] Charles L. Rhodes was then appointed superintendent temporarily.[3][63] He was replaced by George Robinson, a superintendent with the Cleveland & Pittsburgh Railroad. Robinson, who also was the C&M's chief engineer, stayed until 1865.[64]

Completion of the line to Youngstown

The C&M reached Youngstown in the fall of 1856,[lower-alpha 7] and opened for commercial traffic to that city on November 24, 1856.[66] This left the C&M 0.75 miles (1.21 km) short of any connection to an eastern railroad.[67]

Track did not initially extend beyond Youngstown in 1856. In part, the railroad lacked the funds, saying it needed at least $50,000 ($1,600,000 in 2022 dollars) to complete this work.[68] The C&M also discovered that the North Western Railroad at Blairsville was willing to ship freight east but not west, which significantly hindered the new road (as it was costly to ship empty rail cars back to Cleveland).[69]

No additional work on the Cleveland and Mahoning's main line was made after 1857,[20][4] leaving the main line just about 67 miles (108 km) long.[20]

Independent railroad: 1857 to 1863

Early operations

The Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad also failed to complete its northern terminus. Work on the main line had terminated at the docks on the Scranton Flats (not Irishtown Bend), leaving the railroad 0.75 miles (1.21 km) short of its connection with the Cleveland, Columbus and Cincinnati Railroad.[67]

Firming up operations on the existing, incomplete road became the company's immediate goal. It initiated a new bond sale on March 27, 1857,[41] raising $344,100 ($10,800,000 in 2022 dollars).[20] A portion of these funds were used to lessen the steep grade in the Tremont area of Cleveland. The company also purchased 11 more locomotives. To accommodate its growing fleet, the C&M contracted with the Chas. Weatherhead construction firm to build its first maintenance shops and roundhouse In Cleveland, just west of the intersection of Literary Road and Mahoning Avenue.[70][lower-alpha 8] In 1861, the railroad demolished its existing wooden bridge over the Cuyahoga River near Kingsbury Run in Cleveland, and replaced it with an iron Howe truss bridge.[71]

The C&M still needed to find a connection to an eastern railroad. In April 1853, the Pennsylvania General Assembly enacted legislation allowing the C&M to run cars to New Castle, but the statute did not authorize construction of a railroad.[72] This changed in February 1854, when the Pennsylvania legislature amended the law to allow the C&M to build a line "to a point at or near New Castle". These rights, however, only lasted for ten years.[72] The North Western Railroad offered to build a line to the C&M from New Castle, but C&M officials expressed disinterest in this approach[73] because they were already in talks with a different railroad.[74] The Panic of 1857 and opposition from Pittsburgh business and railroad interests (whose city would be bypassed by the connection) ended any further overtures by the North Western Railroad.[73]

Building the Hubbard Branch

As the iron and steel industry in the Mahoning Valley grew significantly after 1856, far less coal was available to send to Cleveland. This loss of freight traffic negatively impacted the C&M's profit margin to a great degree. To solve the problem, the road decided to build a branch from Youngstown into the coal fields around Hubbard, Ohio.[71] To raise funds to build the branch, the railroad sold $72,500 ($2,200,000 in 2022 dollars) worth of new bonds on January 15, 1862.[41] The Hubbard Branch was under construction by February 1863. Initially, railroad officials predicted it would be complete by May 1863,[71] but the dire need for railroad ties and rails brought about by the American Civil War delayed this, and the Hubbard Branch was not finished until 1865.[29] The 12.37 miles (19.91 km) branch[75] extended from the terminus of the C&M's main line in Youngstown to the Ohio-Pennsylvania border.[76][5]

Completion of the C&M to Youngstown led to the significant diminution of traffic on the nearby Pennsylvania and Ohio Canal. Opened in 1840, the canal connected New Castle with Akron, Ohio, by following the Mahoning River and then West Branch of the Mahoning River before cutting cross-country to the city of Kent, Ohio. From there, it largely followed the Cuyahoga River to Akron. With the C&M in financial difficulty due to the loss of coal traffic, the state of Ohio decided in 1863 to sell its stock in the canal to the railroad for $30,000 ($700,000 in 2022 dollars). The sale was intended to give the railroad a new source of revenue, but the C&M barely used the canal. The canal's value was in its right of way, and the C&M later sold most of the canal to the Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Toledo Railroad, which filled it in and used it as the bed for its track.[77]

Operation by the Atlantic and Great Western Railway

C&M involvement in the creation of the A&GW

As early as 1852, the C&M was in talks to make its eastern connection with the Atlantic & Great Western Railway (A&GW).[74] The impetus behind the talks came from the completion in early 1851 of the Erie Railway (then known as the New York and Erie Rail Road) between New York City and Dunkirk, New York (a small town on the shore of Lake Erie halfway between Buffalo, New York, and the New York-Pennsylvania border).[78] On June 30, 1851, the state of New York issued a charter to the Erie and New York City Railroad, giving it authority to build a railroad line from Salamanca, New York, westward through Randolph and Jamestown to the Pennsylvania border. Work began in 1853, but the railroad ran out of money in 1855 and became moribund.[79] Business interests in Ohio greatly desired a cross-state railroad which would link with the Erie at some point. In March 1851, the state of Ohio chartered the Franklin and Warren Railroad (F&W), authorizing it to build a railroad from Dayton, Ohio, to Warren and then east to the Ohio-Pennsylvania border.[78] The F&W investigated the charter of the Pittsburgh and Erie Railroad,[74] which had been chartered in 1846,[80] and discovered that its vaguely-worded charter allowed it to build a railroad from Kinsman, Ohio, to any point in Warren County, New York.[74]

Frederick Kinsman, president of the F&W, invited C&M president Jacob Perkins to meet with representatives of the Pittsburg & Erie, the Clinton Line Railroad, the Erie & New York City, the Cleveland, Painesville and Ashtabula Railroad, and a group of financiers from Meadville, Pennsylvania, on October 1, 1852. The C&M and most of the other railroads present agreed to join forces, and to seek a connection with the Erie Railway. The Erie agreed not only to a connection but also to survey the proposed route across Pennsylvania at its own expense.[74] The Franklin & Warren changed its name in 1853 to the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad (A&GW OH).[78] The A&GW OH began work in August 1853 with funds provided by the Meadville investors, but money ran out after only a few miles were graded.[74]

While the Ohio railroad stalled, in April 1857 the state of Pennsylvania granted a charter to the Meadville Railroad Co. to build a line from Erie, Pennsylvania, to Meadville. The state also gave the Meadville the right to purchase any a branch line constructed under the charter of the Pittsburg & Erie. These rights were purchased in July 1857, but the Panic of 1857 left the Meadville unable to sell any construction bonds. The Meadville changed its name to the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad (A&GW PA) in 1858. Officials of the A&GW PA traveled to the United Kingdom to seek investors, where it won the backing of expatriate railroad financier James McHenry. Additional support came in July 1858 when José de Salamanca, 1st Count of los Llanos sold $1 million ($33,800,000 in 2022 dollars) of A&GW PA construction bonds in Spain. The A&GW PA incorporated a new company, the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad (A&GW NY), in New York state in 1859 and purchased the Erie & New York City.[74] In the first public indication that the Cleveland and Mahoning and all three A&GW roads were working together, the news media reported in March 1859 that the A&GW (a wide-gauge road) had even proposed to add a third rail to the C&M tracks all the way to Cleveland so that no transshipment of freight or passengers need occur.[81]

In January 1860, the A&GW roads announced that they had an agreement to use the C&M to reach Cleveland, even though the latter road still had no connection to any other railroad in the city.[82] The A&GW NY opened between Salamanca and Jamestown in September 1860, and to Corry, Pennsylvania, in May 1861.[74] The outbreak of the Civil War caused funds for construction to dry up,[83] so in August 1861 officials from all three A&GW roads sought out McHenry again. McHenry and the monarchy of Spain both provided more funds to the A&GW. The Trent Affair, which threatened war between the United States and United Kingdom, delayed receipt of these funds slightly. Work resumed in mid-1862, and in February 1863 the English railway magnate Sir Morton Peto made an additional large investment in the three A&GWs (which established a joint board of directors to govern all three companies under the name "Atlantic and Great Western Railroad").[84]

Completing the C&M in Cleveland

The Atlantic & Great Western and the Cleveland and Mahoning connected at Warren some time before May 28, 1863.[85] In July 1863, the A&GW leased the C&M.[84][lower-alpha 9] Part of the lease required the A&GW to complete the last 11.75 miles (18.91 km) of C&M track in Cleveland by May 1, 1864. This meant extending the track to the proposed terminus on Whiskey Island on the Old Ship Channel, as well as completing all necessary side track, turnouts, and docks.[30] In an addendum, the A&GW also agreed to lease the incomplete Hubbard Branch[87] and complete it by January 1, 1864.[30][2]

McHenry advanced the C&M $300,000 ($7,100,000 in 2022 dollars) to enable it to purchase rolling stock.[88] A&GW trains began running on the Cleveland & Mahoning on July 20, 1863.[89] Work on a new passenger depot at the Scranton Flats began in August 1863,[90] and a rail yard for the new depot completed on November 4.[91]

C&M operations under the A&GW

The Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad leased two smaller Ohio railroads on January 1, 1864. The larger road to be leased was the 35-mile (56 km) Niles and New Lisbon Railroad, which the C&M obtained access to for 90 years.[87] This railroad traced its origins to an 1827 charter permitting construction of a 95-mile (153 km) line linking Ashtabula (on the shore of Lake Erie) with the village of New Lisbon in Columbiana County, Ohio. The Ashtabula and New Lisbon Railroad Company began construction on the line in 1853.[16][76] It was only completed between Ashtabula and Niles (a town about halfway between Warren and Youngstown),[76] and in 1864 the uncompleted section was leased to the New Lisbon Railroad Co. This road went bankrupt trying to complete the line.[16][76] The Niles and New Lisbon Railroad purchased the incomplete Niles-to-New Lisbon segment in 1869 and finished construction.[16][76] The smaller road to be leased was the 7.75-mile (12.47 km)[92] Liberty and Vienna Railroad.[87] This road extended from the Church Hill Coal Co. Railroad in Liberty Township[76] (about 5 miles (8.0 km) north of Youngstown) due north to the unincorporated village of Vienna. The route was completed in 1868, and extended west to Girard and then southeast to Youngstown in 1870[16] (a distance of 5.5 miles (8.9 km)).[93] Although the Girard-and-Youngstown branch was sold in 1871 to the Ashtabula, Youngstown and Pittsburg Rail Road,[76] the remainder became part of the C&M.[94][lower-alpha 10]

The Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad's focus on connecting with the A&GW led the C&M to neglect its responsibilities under its Pennsylvania charter. On May 4, 1864, the Pennsylvania General Assembly repealed the C&M's charter, and turned over authority to construct a route between the state line and New Castle to the Lawrence Railroad and Transportation Co.[95] The C&M still sought a direct connection to Pittsburgh, and began seeking an extension of its charter authority in 1866.[2] The Pennsylvania General Assembly refused to approve the charter revision in April 1866,[96] after heavy lobbying against it by Pennsylvania railroads.[97] Committed to reaching New Castle, however, the C&M reluctantly agreed to connect to the Lawrence Railroad once it completed its branch line between New Castle and the Hubbard Branch. (Work on the branch line was completed in March 1867.)[98]

On June 20, 1864, the A&GW, pushing from the west, created another link with the Cleveland and Mahoning. With the western end of the A&GW connecting to the Cincinnati, Hamilton and Dayton Railroad, which gave C&M freight access to St. Louis, Missouri.[84]

A&GW first bankruptcy and Hubbard Branch extension

On August 19, 1865, the three A&GW railroads merged into a new company, the Atlantic and Great Western Railway.[99]

The A&GW went bankrupt in 1867.[100] The A&GW was now leased to the Erie Railway. Beginning in 1867, railroad developer and speculator Jay Gould had waged a successful stock battle for control of the Erie Railway.[101] Gould now began to extend the Erie's reach westward to Chicago, a critical market if his road was to compete with the New York Central Railroad and the Pennsylvania Railroad.[102] His first step in this endeavor was to lease the Erie's long-time partner, the A&GW.[103][lower-alpha 11]

In 1869, the C&M's Hubbard Branch finally gained access to Pennsylvania via trackage rights on two small railroads. The first of these was the Sharon Railway, which was constructed by the Sharon Iron Co. in 1862 to link its iron works with the Brier Hill coal mine in Brookfield Township, Ohio.[104] This 2.09-mile (3.36 km) long industrial railroad extended from the Pennsylvania-Ohio border to Sharon, Pennsylvania,[105] and then slightly north to Pymatuning Junction.[106][lower-alpha 12] The other leased railroad was the Westerman Railroad, completed on May 20, 1864, and constructed by Coleman, Westerman & Co. to connect its iron works with the coal mines in Brookfield Township.[107] This 1.5-mile (2.4 km) long[108] industrial railroad originated in Sharon and extended 0.75 miles (1.21 km) into Ohio.[109] Together, the Sharon Railway and Westerman Railroad pushed the Hubbard Branch a total of 9.85 miles (15.85 km) into Pennsylvania.[110] The C&M obtained trackage rights on both industrial roads, upgraded the line for passenger and freight trains, and ran its first passenger train over them on April 1, 1869.[107]

The A&GW emerged from bankruptcy in 1871 under its old name, the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad,[111] and the lease to the Erie ended.

Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad

1872 creation of the Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad

James McHenry purchased all but 19 shares of the C&M's outstanding stock in April 1872. This stock was then transferred to an investment trust, the Rental Trust Bonds of the Atlantic and Great Western Railway ("the 1872 rental trust").[112]

Recognizing the importance of the Niles & New Lisbon and the Vienna & Liberty shortlines to the C&M, McHenry now moved to ensure that neither line could be taken from him. He sold about $5.5 million ($134,400,000 in 2022 dollars) in bonds to purchase the two roads, and then created a sinking fund for their revenues to repay the debt.[24] On July 25, 1872, the Cleveland & Mahoning, Niles & New Lisbon, and Vienna & Liberty were merged under the laws of Ohio into a new company, the Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad (C&MV).[87][28][2] Over the next several decades, the C&MV made money but the two shortlines did not.[87] The C&MV now began being referred to as the Mahoning Division of the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad.[112]

Second A&GW bankruptcy

Gould lost control of the Erie Railway in March 1872,[113] but the railroad's new managers retained Gould's strategy of trying to reach Chicago.[114] In a lease dated May 1, 1872, but not ratified by stockholders until June 25, the Erie Railway agreed to lease the A&GW for 99 years for an annual rent of $800,000 ($20,700,000 in 2022 dollars) a year. The lease did not cover the C&MV, however, which remained tied only to the AG&W and not the Erie.[115] After Hugh J. Jewett became president of the Erie in July 1874, he discovered that the lease required the A&GW to purchase a controlling interest in the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and Indianapolis Railway, and turn over the stock to the Erie. This the A&GW had not done. Moreover, the A&GW had the right to demand that the Erie deposit an unlimited amount of securities in an Ohio bank of its choosing in order to ensure the good creditworthiness and continuing operation of the A&GW.[116] Jewett declared the lease broken by the A&GW's failure to perform.[117] Its finances destabilized by the loss of rental income and security guarantees, the A&GW went into receivership on December 8, 1874,[118]

The AG&W spent six years drifting through bankruptcy.[119] As it did, the C&MV expanded its route slightly when the Sharon Railway extended its line to Shenango Junction[lower-alpha 13] in 1876.[120] In 1877, Chagrin Falls businessman William Hutchings constructed a 5-mile (8.0 km) branch from Chagrin Falls to the C&MV main line.[121]

Nypano lease of the C&MV

The A&GW finally emerged from bankruptcy in 1880. The company owed more than $60 million ($1,551,900,000 in 2022 dollars), and most of its rolling stock had been repossessed for lack of payment. It was widely believed in the railroad industry that the A&GW could be made profitable with the expenditure of about $5 million ($137,400,000 in 2022 dollars), which would allow it to be converted to standard-gauge and purchase enough rolling stock to make it operational again. The Erie Railway (now formally known as the New York, Lake Erie and Western Railroad), still seeking a western main line, agreed to raise the money. The A&GW would be permitted to retain two-thirds of its earnings, with the remaining one-third going to the Erie. In England, McHenry and the other owners of the "1872 investment trust" were outraged: They had purchased more than $50 million ($1,293,200,000 in 2022 dollars) in AG&W stock and $70 million ($1,810,500,000 in 2022 dollars) in AG&W bonds, and had seen no return. They initiated several lawsuits which delayed the A&GW's emergence from bankruptcy for three years.[116] Finally, on March 16, 1880, the five trustees of the A&GW organized a new company, the New York, Pennsylvania and Ohio Railroad (NYP&O, pronounced "Nip-ah-no"), on behalf of the bondholders.[122] The Atlantic & Great Western was sold to the NYP&O on March 20, 1880.[123]

On June 22, 1880, the C&MV was converted to standard-gauge in a single day.[31]

In order to retain control of the C&MV, the NYP&O executed supplemental leases with the road on May 4, 1880, and again on April 24, 1883.[28] The NYP&O converted the C&MV's trackage rights on the Westerman Railroad into a formal lease on January 1, 1886.[109]

In the spring of 1886, the NYP&O completed the C&MV route in Cleveland, at last making the connection to another railroad.[55] To cross the peninsula between the Old Ship Channel and the Irishtown Bend, the track bed was placed in a channel, with Hemlock, Maine, Washington, and Winslow Avenues passing over the tracks via stone bridges.[124][lower-alpha 14] Trains began running July 4.[55] The C&MV's rail yards extended for nearly 2 miles (3.2 km)[125] along the southwest bank of the Old Ship Channel, around Irishtown Bend, and in Tremont.[124] The NYP&O replaced the C&MV's bridge over the Cuyahoga River at Kingsbury Run with a jackknife bridge, and rebuilt the bridge over Kingsbury Run itself.[125] The NYP&O also built a new C&MV dock just north of where the C&MV tracks curved westward to pass under Detroit Avenue.[126]

Fourth Erie lease

On March 6, 1883, the Erie Railroad leased the NYP&O.[127]

By 1886, the C&MV was the NYP&O's most important line, generating 55 percent of the entire NYP&O's 6,045,000 short tons (5,484,000 t) of annual freight. There was so much freight traffic on the C&MV that the line was overloaded. Its docks in Cleveland were still not automated, and the use of manual labor left so much freight backed up that the docks actually moved less freight in 1886 than they did in 1885.[128]

A joint study of the situation by the Erie and C&MV, released in February 1888, recommended that the line between Cleveland and Youngstown finally be double-tracked at a cost of $1.25 million ($40,700,000 in 2022 dollars). The study also recommended, among other things, that new steam-powered unloaders be built at the Cleveland docks at a cost of $250,000 ($8,100,000 in 2022 dollars).[128]

Double-track work began in May 1888 with the successful sale of new bonds.[129][130] Work commenced in the early fall of 1888.[131] To cut costs, the C&MV prefabricated each short bridge and carried it to the worksite en toto on flatbed cars. There, the bridges were placed on skids before being winched into place using hand-powered derricks. Larger bridges were prefabricated in pieces, and set into place the same way. In only one case, that of the longest bridge on the line, did the railroad need to build a temporary trestle to carry the track while a new bridge was put in place.[132] The C&MV found, however, that it had too few funds on hand to complete the double-tracking and build all the required rail yards. Officials decided to regrade the entire road for double track, but only lay 56 miles (90 km) of rail.[131] The double-tracking effort ended in 1890, with just 10 miles (16 km) of track left to double.[133]

Erie ownership of the Nypano

The NYP&O once more fell into financial difficulty in 1895. The Erie Railroad agreed to purchase all the debt and stock of the road on January 1, 1896. The NYP&O was reorganized on March 16, 1896, as the Nypano Railroad Company.[134] The Erie continued to lease the C&MV as well. This latest lease gave the Erie control of the road until March 1, 1962, in exchange for an annual rent of $514,180 ($18,100,000 in 2022 dollars).[129]

A number of changes were made to the C&MV over the next 35 years. The railroad was realigned between Hubbard and Chestnut Ridge (County Highway 12 to the northeast), and several tight curves improved.[135] The Sharon Railway purchased the New Castle and Shenango Valley Railroad in November 1900, finally giving the C&MV a connection to New Castle. On January 1, 1901 (retroactive to December 1, 1900), the Nypano leased the Sharon Railway for 900 years.[120] The new lease allowed the C&MV to abandon the rarely-profitable Vienna & Liberty Railroad, which it did in 1901.[136] The Nypano spent $3 million ($101,500,000 in 2022 dollars) on C&MV track, depot, and yard improvements in 1903.[137] Fifteen bridges were replaced in 1905, including a two-span bridge over the Shenango River at Sharon.[138] In 1941, the Nypano leased a portion of the Cleveland & Pittsburgh Railroad line in Ravenna, Ohio. This 2.5 miles (4.0 km) piece of track became the Mahoning Division's main line (giving the division a better route through the city than its existing double-tracked and single-tracked lines). The Erie purchased this track in 1945.[139] In 1912, the Nypano replaced the damaged swing bridge over the Cuyahoga River north of Kingsbury Run with a new 180-foot (55 m), double-tracked, single-leaf Strauss bascule bridge.[140]

The Nypano built a new, steam-operated coal tipple and dock for the C&MV in 1912, near what is now the western abutment of the Detroit-Superior Bridge. It was designed by Wellman Engineering, a prominent Cleveland firm.[141] C&MV traffic along the Cuyahoga River in Cleveland was so extensive, the C&MV expanded its rail yard at Irishtown Bend to eight tracks to accommodate it.[142] Construction on the Detroit-Superior Bridge began in 1914, The coal tipple was moved 200 feet (61 m) upstream in 1917 to accommodate the bridge.[141]

On March 9, 1917, the Nypano signed a new, amended lease with the C&MV. This lease gave the Nypano control of the road for 999 years in exchange for an annual rent of $558,967 ($12,800,000 in 2022 dollars) (plus taxes).[28]

In the mid-1920s, the Erie Railroad fell under the control of the Nickel Plate Securities Corporation. This company had been established in 1915 by O. P. Van Sweringen and M. J. Van Sweringen ("The Vans"), two brothers from Cleveland. The Vans were real estate developers who had been frustrated in their attempts to win construction of a streetcar line from their Shaker Heights, Ohio, development to downtown Cleveland. In April 1916, the Vans purchased a controlling interest in the New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad (known as the "Nickel Plate Railroad"), whose charter permitted a rail line into downtown Cleveland. To protect their Nickel Plate investment, the Vans began acquiring other railroads as well. As part of this strategy, from November 1924 to January 1925 the Vans purchased enough stock in the Erie Railroad to take control of that property.[143]

Erie Railroad purchase of the Cleveland and Mahoning Valley

The complex system of holding companies and loans which the Vans used to build their railroad empire collapsed in 1933 with the onset of the Great Depression.[144]

As the Van Sweringen railroads struggled with bankruptcy, the Erie Railroad sought ways to cut costs. The company was still paying $558,967 to the British stockholders of the C&MV, even though income from the line had fallen far below that. Erie officials learned that the stockholders, many of whom needed cash to help them get through the depression, would be willing to sell.[145] The Erie needed a loan to pay for the transactions. It approached the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which in mid-October 1939 approved the loan.[146][147] The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) approved the $7.9 million ($166,200,000 in 2022 dollars) purchase on November 16.[148]

This left only the Nypano (the C&MV's lease-holder) and the C&MV's bondholders as the only obstacle to the Erie's complete ownership of the Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad. In 1941, the Erie sought approval from the ICC to sell $18 million ($358,100,000 in 2022 dollars) in bonds. This would allow the Erie to purchase the Nypano and pay off the C&MV's existing bonds. The ICC approved the bond sale on September 15, 1941,[149] and the purchase of the Nypano and C&MV bonds on October 28.[150] A bankruptcy court gave its approval on December 19, 1941, when it allowed the Erie to emerge from bankruptcy.[151]

The Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad's existence as an independent corporation came to a close on May 7, 1942.[152]

Post-Erie status

The C&MV now became known as the Mahoning Division of the Erie Railroad.[153][lower-alpha 15] About 1.5 miles (2.4 km) south of Transfer, Pennsylvania, the double track became two parallel tracks. The southern set of tracks (the former Hubbard Branch) kept to the valleys and passed through Sharon to reach Youngstown before moving northwest to Warren. These tracks the Erie called the "First Subdivision". The second set of tracks stuck to the higher ground, and swung more westerly to reach Warren's north side via a more direct route. These tracks the Erie called the "Second Subdivision".[155] As both subdivisions left Warren's city limits, they became parallel again.[156] The two tracks crossed just west of Leavittsburg (a location known as "SN Junction"), with all passenger trains taking the First Subdivision (which became double-tracked again).[157]

The Erie Railroad closed the former C&MV freight docks at Columbus Road on Irishtown Bend on May 31, 1946.[158] At some point, either the C&MV or the Erie had moved the main passenger and freight station away from Scranton Flats to a new depot located west of E. 93rd Street and Harvard Avenue in Cleveland's Union-Miles Park neighborhood. In January 1948, the Erie announced it would construct a new passenger station at E. 131st Street and Miles Avenue. about 0.5 miles (0.80 km) to the east.[159] By July, these plans had changed: Now the Erie intended to build a 50 by 19 feet (15.2 by 5.8 m) passenger-only depot at the intersection of Lee Road and Miles Avenue, a full mile southeast of the existing location. This would no longer be the main depot, either, but merely a station to give suburban passengers easier access.[160] The Erie's main station shifted to Cleveland Union Station, the massive train station erected in 1927 by the Van Sweringens beneath Terminal Tower.[161]

Erie Lackawanna Railroad and Conrail ownership

On October 17, 1960, the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad merged with the Erie Railroad to become the Erie Lackawanna Railroad.[162] The Erie Lackawanna made major repairs to the former C&MV track near the Detroit-Superior Bridge in late 1960 after it was discovered that the track bed and subsided significantly. A later investigation concluded that saturated soil, caused by either a nearby broken water line or an unknown natural spring, was the culprit.[163] In 1964, the Erie Lackawanna canceled all intercity passenger train traffic on the old C&MV, leaving a Cleveland-to-Youngstown commuter train as the only regularly scheduled passenger service on the line.[164]

The Erie Lackawanna filed for bankruptcy on June 26, 1972, after Hurricane Agnes devastated much of its track.[165]

The Erie Lackawanna lingered in bankruptcy until 1976. A number of other northeastern railroads had also gone bankrupt, and in 1975 Congress enacted legislation creating Conrail, a quasi-governmental corporation with authority to take over the bankrupt roads, improve them, abandon unprofitable branches and main lines, and make freight traffic profitable again. Conrail took over the Erie Lackawanna and the other railroads on April 1, 1976.[166]

Conrail renamed the C&MV track, calling the old First Subdivision the "Randall Secondary"[167] and the old Second Subdivision the "Freedom Secondary".[168]

Changes under Conrail

Conrail abandoned the 31-mile (50 km) Lisbon Branch immediately after taking over the Erie-Lackawanna.[169] Conrail then ended Cleveland-to-Youngstown commuter service on January 14, 1977.[170][lower-alpha 16]

Conrail began trimming its freight service on the old C&MV in the 1980s. The railroad began moving freight traffic onto its Cleveland Line (the old Cleveland & Pittsburgh Railroad) in the late 1970s and early 1980s, leaving the Randall and Freedom Secondaries with almost no traffic.[172] It abandoned the C&MV line east of Mantua in 1981,[173] and the line between Hubbard and Sharon in 1982.[174] It removed 22 miles (35 km) of track between Mantua and Leavittsburg in 1982,[175] and in 1982 and 1983 it removed portions of its track within the cities of Warren (1.6 miles (2.6 km))[176] and Youngstown (1.39 miles (2.24 km)).[177]

In 1982, Conrail removed 3.3 miles (5.3 km) of track in Cleveland, from the terminus on Whiskey Island to its Von Willer Yard (at E. 93rd Street and Harvard Avenue).[178] About 1993, Conrail abandoned the remainder of the Randall Secondary east of Chamberlain Road.[179][lower-alpha 17]

Some of the former C&MV main line in Cleveland was lost to road construction in the 1980s. Riverbed Street had, for many decades, been a single-lane road which paralleled the most inland track at Irishtown Bend. The road was widened to two lanes in 1985, with the new eastern lane covering this track.[142]

In July 1993, Conrail sold the 35-acre (140,000 m2) former C&MV rail yards on Whiskey Island to Whiskey Island Partners, a real estate development corporation, for $1.6 million ($3,200,000 in 2022 dollars).[180] The private company spent $300,000 moving Conrail's track off Whiskey Island.[181] In December 2004, Cuyahoga County purchased the land from the Whiskey Island Partners, as well as the rest of Whiskey Island, for $6.25 million ($9,700,000 in 2022 dollars).[182] The county used most of the peninsula to create Wendy Park.[183]

Conrail sold in June 1994, among other assets, a 7.2-mile (11.6 km) segment of the Freedom Secondary between Kent and Ravenna to the newly formed Akron Barberton Cluster Railway.[184] This portion of track was later sold to the Portage Private Industry Council, and in 2004 to the Portage County Port Authority (which continued to lease it to the Akron Barberton Cluster Railway).[185]

In 1996, the Warren and Trumbull Railroad gained access to two sections of former C&MV track. In May, Conrail sold a 5-mile (8.0 km) segment of the Freedom Secondary between North Warren and Leavittsburg to the newly formed Economic Development Rail II Corporation, a nonprofit organization created by the Mahoning Valley Economic Development Corporation. This portion of track was leased to the Warren and Trumbull Railroad.[186] The following August, the Warren and Trumbull Railroad Company purchased 12.9 miles (20.8 km) of Randall Secondary and Freedom Secondary main line, spurs, and siding (the "Lordstown Cluster Lines").[187]

In January 1997, the Youngstown Belt Railroad purchased about 3 miles (4.8 km) of Randall Secondary main line, spurs, and siding between West Crossing in Youngstown and Weathersfield Township.[188]

Norfolk Southern ownership

In 1998, most of Conrail was acquired by CSX Transportation and the Norfolk Southern Railway, which divided the company between them. The Norfolk Southern (NS) ended up with the Randall Secondary.[179]

In June 2009, the Cleveland Commercial Railroad (CCR) signed an agreement in which it leased 25 miles (40 km) of the Randall Secondary (between the Von Willer Yard and the end of functioning track east of Aurora).[189] The NS and CCR both proposed in June 2017 abandoning the 5.5 miles (8.9 km) of the line west of Chamberlain Road, and removing the track.[190]

About the C&MV line

Main line and branches

The Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad's main line ran from Cleveland to Youngstown, and was originally 67.81 miles (109.13 km) long.[75][lower-alpha 18] Siding and other track along the main line totaled 10 miles (16 km) in 1867,[86] but after completion of the line and significant expansion of yards it totaled 209.76 miles (337.58 km) in 1922.[28] Completion of the main line by the Atlantic & Great Western Railway left the main line 80.81 miles (130.05 km) long.[129] Doubled (or "secondary") track along the route was initially 65.72 miles (105.77 km) in 1898,[129] but had reached 77.29 miles (124.39 km) by 1922.[28]

The Hubbard Branch began in Youngstown and ran through Hubbard to the Ohio-Pennsylvania border, a distance of 12.37 miles (19.91 km).[75]

The Niles & New Lisbon Railroad (later known as the Lisbon Branch) ran from Niles to a point about 3 miles (4.8 km) south of New Lisbon, a total distance of 36.25 miles (58.34 km).[129][105]

The Liberty & Vienna Railroad (later known as the Liberty Branch) ran from Liberty Township to the village of Vienna, a distance of about 7.75 miles (12.47 km).[92]

The Westerman Railroad and Sharon Railway extended the Hubbard Branch 9.85 miles (15.85 km) to Pymatuning Junction in Pennsylvania.[110]

Description of the line

After completion of the double-track, the Cleveland and Mahoning Valley Railroad had a grade of 0.398 going west and 0.49 going east. The grade was a much steeper 1.1 from the shore of Lake Erie to the heights of Cleveland.[6] The steep grade from the heights to the shore meant that trains were limited to just 130 cars past the North Randall yard.[125]

About milepost 41, near Garrettsville, the huge Mahoning Siding had spurs to numerous sand and gravel quarries in the area, and provided extensive holding areas for ore cars as they awaited connection to a freight train.[192] The two tracks of the main line crossed one another just west of Leavittsburg (a location known as "SN Junction").[157] In the city limits of Warren, the double track became a gauntlet track.[193]

By the late 1950s, the Brier Hill Yard at Youngstown was 25 tracks wide and 1.5 miles (2.4 km) long. The main line was actually triple-tracked here so that sleeper car trains would not be delayed. Southeast of Crab Creek was Himrod Junction, where trains bound for Pittsburgh could veer southeast and connect with another Erie subdivision. Trains headed for Hoboken, New Jersey, stayed on the C&MV.[194]

Between Hubbard and Sharon, the line single-tracked for 3.5 miles (5.6 km). Trains also single-tracked over the Shenango River and across the Pymatuning Swamp. Double-tracking began again at Pymatuning Junction.[195]

Headwaters Trail

Beginning about 1993, Portage County began acquiring 7 miles (11 km) of abandoned Randall Secondary track between Mantua and Garrettsville. By 1997, it had assembled the entire segment from various landowners, and the parcels were renamed the Headwaters Trail. A $50,000 ($100,000 in 2022 dollars) bequest enabled the newly created Portage County Park District to begin grading the right of way and turning it into a biking aned hiking trail. The eastern portion of the trail was completed about October 1997.[196] The western portion, paid for by a $99,000 ($100,000 in 2022 dollars) grant from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources (ODNR), opened the following year.[197] The park district was able to obtain a missing 1.5-mile (2.4 km) long section of abandoned track[198] in 2003 for $46,000, enabling the eastern and western segments of the trail to connect.[199]

The park district acquired an additional 1.35 miles (2.17 km) of abandoned track at the western end of the trail in November 2017. A $60,000 ($100,000 in 2022 dollars) grant from the ODNR allowed the park district to resurface the entire length of the trail in 2018.[200] The same month, the park district signed a purchase agreement to obtain 0.8 miles (1.3 km) of abandoned track at the eastern terminus of the Headwaters Trail.[201][lower-alpha 19]

Cleveland Foundation Centennial Lake Link Trail

In 1987,[203] a series of archaeological digs at Irishtown Bend led to a report that recommended protecting the site.[204] Following up on this recommendation, the Cuyahoga County Planning Commission released a report in April 1992 that proposed a biking and hiking trail along the old C&MV track bed at Irishtown Bend and the Scranton Flats to link Whiskey Island in the north with the Ohio and Erie Canal Towpath Trail in the south.[205] In January 2009, a group spearheaded by the city of Cleveland issued a report which once more called for turning the abandoned trackbed between Whiskey Island and the Towpath Trail into a biking-hiking trail. The plan also included the construction of a new pedestrian bridge over the Old Ship Channel of the Cuyahoga River to reconnect the tracks with the old C&MV rail yard (now part of Wendy Park).[206]

Negotiations to obtain title to the C&MV trackbed began in 2008. The Trust for Public Land (TPL), a national nonprofit which coordinates and facilities the creation of parkland, negotiated on behalf of the group with Westbank Development Corp.[206] On December 28, 2009, TPL purchased for $3.2 million ($4,400,000 in 2022 dollars) title and an easement covering 1.3 miles (2.1 km) of former C&MV trackbed between the Old Ship Channel and the Cuyahoga River near Kingsbury Run.[207]

Cleveland Metroparks oversaw initial design work for the proposed trail, which began in 2009.[207] The agency began bridge design work in 2014.[208] A February 2015 restudy of Irishtown Bend geologic instability, issued by the Cleveland-Cuyahoga County Port Authority, led to a delay in constructing trail along Irishtown Bend until the hillside was permanently stabilized.[209]

The 0.25-mile (0.40 km) southern leg of the Cleveland Foundation Centennial Lake Link Trail opened on August 13, 2015. This leg began at the northern terminus of the Ohio & Erie Canal Towpath Trail and crossed the base of the Scranton Peninsula before terminating at Columbus Road on the eastern side of Irishtown Bend.[210] The 0.5-mile (0.80 km) northern leg of the Cleveland Foundation Centennial Lake Link Trail opened on June 9, 2017. This leg ran from the Detroit-Superior Bridge northwest and west to the Old Ship Channel.[211][212]

Cleveland Metroparks said it would seek bids to build the Whiskey Island pedestrian bridge before the end of 2017.[211] The agency said it hoped to begin construction on the bridge in the summer of 2018, and complete work at the end of 2019.[213]

See also

References

- Notes

- The North Western Railroad had completed its line from New Castle to Blairsville, Pennsylvania, in 1854.[18]

- As of October 1853, the Ohio & Pennsylvania Railroad was being constructed along the valley of the Beaver River from New Brighton to New Castle.[6]

- Chagrin Falls businessmen were extremely angry about the decision. They pointed out that the village had purchased $30,000 ($1,100,000 in 2022 dollars) in stock, and should have been on the route.[33]

- The decision proved fortuitous; the village of Mantua was founded around the C&M's depot.[34]

- Collision Bend is an oxbow in the Cuyahoga River which defines the peninsula that contains the Scranton Flats.

- The Portage Escarpment acts as a moderately high bluff or ridge[44] cutting across Cleveland roughly northeast to southwest. It parallels the shore of Lake Erie at a distance of about 3 miles (4.8 km) until it reaches Painesville, where it begins to curve ever more sharply to the southwest and south. In Newburgh Township, it extend from Doan's Corners (located roughly at the modern intersection of Euclid Avenue and E. 105th Street) southwest, south, and southwest again to the old Newburgh Village.[45] Northwest and west of the ridge, the terrain is relatively flat. It rises gradually in a series of sandy ancient beach ridges left by Lake Erie at a time when the lake was much larger than it is today. East and southeast of the ridge, glacial moraine covers the Allegheny Plateau as it rises gradually toward the Appalachian Plateau.[46] This area is hilly, cut through by numerous dry ravines.[47]

- The track roughly paralleled the east bank of the Mahoning River. It reached Crab Creek in Youngstown, and then stopped.[65]

- This work included a 120-by-75-foot (37 by 23 m) machine shop and repair shop, a 15-by-20-foot (4.6 by 6.1 m) boilerhouse, and a 200-foot (61 m) wide, $20,000 ($600,000 in 2022 dollars) roundhouse with 20 locomotive stalls and a turntable. The work began in August 1857, and was completed three months later.[70]

- Most sources say the lease dates to October 1[86] or October 7.[2][87] Erie Railroad historian Edward H. Mott says the lease dates to July 1863.[84] Mott's claim is probably more reliable, given the work the news media said the A&GW did on the C&M tracks prior to October 1863.

- This required the C&M to build a 1.65-mile (2.66 km) connection from Youngstown to Liberty Township.[28]

- There were, in fact, two leases. The court-appointed receiver leased the A&GW to the Erie Railway in 1868. The first receiver was removed, and a new receiver appointed. The second receiver leased the A&GW again to the Erie in 1869.[100]

- Pymatuning Junction was a connection with the Erie Railway located about 1,500 feet (460 m) east of the intersection of what is now Carrier Road (Township Road 428) and W. Lake Road (Township Road 587) in Mercer County.

- This is an unincorporated hamlet located 1 mile (1.6 km) south of Greenville, Pennsylvania, on what is now Pennsylvania Route 18.

- The earliest of these bridges, built in 1853, allowed Detroit Avenue to pass over the tracks. As of 1981, it was the oldest bridge still in use in Cleveland.[124]

- The Erie Railroad considered the Mahoning Division to extend northeast past Shenango to 1 mile (1.6 km) past Meadville, Pennsylvania.[154]

- Long-distance intercity passenger trains stopped using Terminal Tower in 1972.[171]

- The location is east of Aurora, Ohio, a few hundred feet north of the intersection of Chamberlain Road and E. Pioneer Trail.

- Sources note that the southern terminus was originally Girard, and that the line was later extended 6 miles (9.7 km) to Crab Creek in Youngstown.[129][28][105] This segment was also known as the "Canal Branch".[191]

- The Headwaters Trail does not include the former C&MV depot at Mantua. However, that station is an architectural and historical landmark protected by the Village of Mantua.[202]

- Citations

- Orth 1910c, p. 1067.

- Kennedy 1885, p. 602.

- History of Trumbull and Mahoning Counties 1892, p. 104.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1868a, p. 41.

- Brown & Norris 1885, p. 291.

- "Exhibit of the Conditions and Prospects of the Cleveland and Mahoning Railway Company". American Railroad Journal. October 29, 1853. p. 692. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- Reynolds, Gifford & Ilisevich 2002, p. 26.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad". The Plain Dealer. September 12, 1851. p. 2.

- Rose 1990, p. 250.

- Kennedy 1896, p. 305.

- Upton 1910, pp. 32–33.

- Jordan 1911, pp. 578–579.

- Upton 1910, p. 11.

- Comley & D'Eggville 1875, p. 136.

- Miller 2015, p. 348.

- Butler 1921, p. 761.

- Albert 1882, p. 403.

- Wilson 1899, p. 212.

- "Cleveland & Mahoning Rail Road—The Destiny of Cleveland as a Manufacturing City". The Plain Dealer. January 6, 1853. p. 2.

- "Annual Report of the Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad". The Plain Dealer. January 25, 1861. p. 3.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad". The Plain Dealer. December 27, 1852. p. 2.

- "With and Without Glasses". The Plain Dealer. April 8, 1894. p. 9.

- Avery 1918, p. 560.

- "Atlantic and Great Western". The Railway Times. April 10, 1875. p. 362. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- Sanders 2007, p. 33.

- Romans 1899, p. 67.

- Puffert 2009, p. 117.

- Moody 1922, p. 97.

- Erie Magazine 1958, p. 12.

- Works Progress Administration 1939, pp. 139–140.

- Camp 2007, p. 33.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad—President and Engineer's Report". The Plain Dealer. January 24, 1853. p. 3.

- "The Chagrin Falls Branch of the Cleveland and Mahoning R. R.". The Plain Dealer. April 30, 1853. p. 3.

- Brown & Norris 1885, p. 483.

- "New Railroad Project". The Plain Dealer. March 24, 1853. p. 2.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad—President and Engineer's Report". The Plain Dealer. January 25, 1853. p. 3.

- MacKeigan 2011, p. 28.

- "Mahoning Rail Road". The Plain Dealer. March 5, 1853. p. 3.

- "Cleveland, Mahoning, Britton, Warren, Youngstown". The Plain Dealer. May 31, 1853. p. 3.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad". The Plain Dealer. August 27, 1853. p. 2.

- Interstate Commerce Commission 1931, p. 461.

- "The North-Western, and Cleveland and Mahoning Railroads". The Plain Dealer. February 27, 1854. p. 2.

- "Mahoning Construction Progressing". The Plain Dealer. July 10, 1854. p. 3.

- Leading Manufacturers and Merchants of the City of Cleveland and Environs 1886, p. 23.

- Orth 1910a, p. 101.

- Winslow, White & Webber 1953, p. 5.

- MacKeigan 2011, p. 50.

- "Cleveland & Mahoning Rail Road". The Plain Dealer. July 24, 1854. p. 3.

- Kennedy 1885, pp. 602–603.

- "New Railroad—Make way for the Mines of Mahoning". The Plain Dealer. April 20, 1855. p. 2.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad". The Plain Dealer. May 28, 1855. p. 3.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad". The Plain Dealer. July 26, 1855. p. 3.

- "Arrivals of R. R. Iron". The Plain Dealer. October 19, 1855. p. 3.

- "In North Randall, It's Almost All Business". The Plain Dealer. April 6, 1996. p. E3.

- Brown & Norris 1885, p. 292.

- "Mahoning Valley Railroad". The Plain Dealer. November 30, 1855. p. 2.

- "The Mahoning Rail Road". The Plain Dealer. June 30, 1856. p. 3.

- "Municipal Affairs". The Plain Dealer. March 19, 1856. p. 3.

- "Ohio Railroads". The Plain Dealer. April 11, 1856. p. 3.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad". The Plain Dealer. June 27, 1856. p. 4.

- "Unclassified". The Plain Dealer. June 16, 1856. p. 3.

- "Change". The Plain Dealer. July 17, 1856. p. 3.

- "Election Returns". The Plain Dealer. January 30, 1857. p. 3.

- Brown & Norris 1885, p. 846.

- "C.&M. Railroad". The Plain Dealer. April 16, 1858. p. 3.

- "Cleveland & Mahoning R.R. Time Table Number 3". The Plain Dealer. November 25, 1856. p. 2.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad". The Plain Dealer. July 6, 1857. p. 1.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad". The Plain Dealer. January 28, 1857. p. 2.

- "Cleveland and Her Rail Roads". The Plain Dealer. May 30, 1857. p. 1.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Rail Road Shops". The Plain Dealer. August 6, 1857. p. 3.

- "Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad". American Railroad Journal. February 7, 1863. pp. 118–119. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1871, p. 547.

- Churella 2013, pp. 306, 633.

- Mott 1901, p. 364.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1868a, p. 44.

- History of Trumbull and Mahoning Counties 1892, p. 105.

- Brown & Norris 1885, p. 290.

- Mott 1901, p. 363.

- Mott 1901, pp. 363–364.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1871, p. 556.

- "Rail Road War and Rumors of War". The Plain Dealer. March 14, 1859. p. 2.

- "The Atlantic and Great Western R. R.". The Plain Dealer. January 30, 1860. p. 3.

- Mott 1901, pp. 364–365.

- Mott 1901, p. 365.

- "The Atlantic & Great Western Railroad". The Plain Dealer. May 28, 1863. p. 3.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1868a, p. 53.

- Swinburne, John (July 3, 1875). "Atlantic and Great Western". The Railway Times. pp. 649–651. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- Weber 1999, p. 17.

- "New Route From Cleveland to New York". The Plain Dealer. July 17, 1863. p. 3.

- "The Atlantic & Great Western Railroad". The Plain Dealer. August 12, 1863. p. 3.

- "Completion of the Atlantic & Great Western Railroad to Cleveland". The Plain Dealer. November 5, 1863. p. 3.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1884, p. 710.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1874, p. 71.

- Butler 1921, p. 762.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1871, pp. 547–548.

- "The Pittsburg Press on the Defeat of the Cleveland and Mahoning Railroad Bill". The Plain Dealer. April 10, 1866. p. 2.

- Sanders 2014, p. 21.

- "Railroad Matters". The Plain Dealer. March 25, 1867. p. 4.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1881, p. 1026.

- Finkelman 2001, p. 55.

- Morris 2006, pp. 62–66.

- Morris 2006, p. 67.

- Morris 2006, pp. 67–68.

- History of Mercer County, Pennsylvania 1888, pp. 195–196.

- Pennsylvania Bureau of Railways 1903, p. 97.

- Erie Railroad Company 1888, p. 35.

- History of Mercer County, Pennsylvania 1888, p. 176.

- Ohio Commissioner of Railroads and Telegraphs 1873, p. 50.

- Sanderson 1907, p. 233.

- Poor 1889, p. 213.

- "Another Chapter of Erie". Railway Age. September 29, 1905. p. 384. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- "Cleveland & Mahoning Valley Railroad". The Commercial and Financial Chronicle. October 18, 1873. p. 512. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- Morris 2006, p. 77.

- Schafer 2000, pp. 47–48.

- "Old and New Roads". Railroad Gazette. July 4, 1875. p. 257. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- Mott 1901, p. 237.

- Mott 1901, pp. 237, 240.

- "Atlantic and Great Western". The Railway Times. January 2, 1875. pp. 22–23. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- Mott 1901, p. 262.

- Moody 1922, p. 98.

- Farkas, Karen (August 16, 1992). "Bustling Little Town Lost in Time". The Plain Dealer. p. B1.

- Ohio Secretary of State 1881, p. 1029.

- Ohio Secretary of State 1881, p. 162.

- Watson & Wolfs 1981, p. 58.

- Erie Magazine 1958, p. 13.

- Watson & Wolfs 1981, p. 59.

- Springirth 2010, p. 75.

- "Railway News". Railway World. February 18, 1888. p. 155. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- Poor 1899, p. 121.

- "To Double Track the Mahoning Valley Road". The Plain Dealer. May 19, 1888. p. 8.

- Erie Railroad Company 1888, p. 13.

- Bianculli 2003, p. 92.

- "New York Pennsylvania & Ohio Railroad". The Commercial and Financial Chronicle. November 18, 1891. p. 796. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- New York Board of Railroad Commissioners 1897, p. 700.

- Erie Railroad Company 1899, p. 17.

- Moody 1922, pp. 97–98.

- "American and Canadian Railway News". The Railway News. July 5, 1902. p. 12. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- "Erie Railroad Improvements". Trust Companies. July 1905. p. 567. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- Erie Magazine 1958b, p. 29.

- "Replacing the Cuyahoga River Draw Bridge". Engineering Record. January 4, 1913. pp. 20–21. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- Dean, Jewell R. (June 2, 1946). "Busy Six Months Indicated for Great Lakes Carriers". The Plain Dealer. p. C13.

- Barr and Prevost 2015, p. 4.

- Ellenberger & Mahar 1973, p. 368.

- Harwood 2003, pp. 260–270.

- Grant 2001, p. 28.

- Grant 2001, pp. 28–29.

- "Construction". Railway Age. October 14, 1939. p. 606. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- "Leased-Line Deal of Erie Approved". The New York Times. November 17, 1939. p. 33.

- "Erie Road Plans Securities Sale". The New York Times. September 16, 1941. p. 31.

- "Erie to Buy 2 Roads". The New York Times. October 29, 1941. p. 33.

- "Court to Set Free Erie Road Today". The New York Times. December 20, 1941. pp. 29–30.

- Holm & Dudley 1957, p. 164.

- Rose 1990, p. 322.

- Erie Magazine 1958b, p. 12.

- Erie Magazine 1958b, pp. 14, 26.

- Erie Magazine 1958b, p. 27.

- Erie Magazine 1958b, p. 28.

- Dean, Jewell R. (June 1, 1946). "Marine News". The Plain Dealer. p. 10.

- "New Erie Station Plans Nearly Set". The Plain Dealer. January 16, 1948. p. 11.

- "Erie Railroad Will Build New Station at Lee and Miles". The Plain Dealer. July 1, 1948. p. 4.

- "Erie To Shift To Terminal in 1949". The Plain Dealer. July 30, 1948. pp. 1, 7.

- "New Rail System Selects Officers". The New York Times. October 18, 1960. pp. 55, 64.

- Barr and Prevost 2015, pp. 2, 9–10.

- "Hearing Set on Erie Aim to Cut Service". The Plain Dealer. September 10, 1964. p. 23.

- Bedingfield, Robert E. (June 27, 1972). "Erie Road, Citing Flood, Files for Reorganization". The New York Times. pp. 1, 81.

- Bedingfield, Robert E. (April 1, 1976). "Conrail Takes Over Northeast's System". The New York Times. pp. 43, 47.

- Surface Transportation Board 1998, p. R-90.

- Transportation Economics and Management Systems & HNTB 2007, p. 2—19.

- "Ohio Rail Lines To Be Phased Out As ConRail System Becomes Reality". The Press-Gazette. March 31, 1976. p. 8. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Doll, Bill (January 15, 1977). "It Was All Aboard—The Final Time". The Plain Dealer. p. 19.

- Nussbaum, John (January 14, 1977). "All Aboard Tonight". The Plain Dealer. p. 7.

- Sanders 2016, p. 58.

- Sanders 2014, p. 30.

- "Consolidated Rail Corporation. AB 167, Sub 32". Interstate Commerce Commission. September 15, 1981. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- "Consolidated Rail Corporation. AB 167, Sub 302". Interstate Commerce Commission. November 30, 1981. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- "Consolidated Rail Corporation. AB 167, Sub 174N". Interstate Commerce Commission. November 30, 1981. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- "Consolidated Rail Corporation. AB 167, Sub 456N". Interstate Commerce Commission. January 18, 1983. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- "Consolidated Rail Corporation. AB 167, Sub 220N". Interstate Commerce Commission. November 23, 1981. Retrieved November 19, 2017; "Consolidated Rail Corporation. AB 167, Sub 175N". Interstate Commerce Commission. November 30, 1981. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Parsons Brinckerhoff 2001, p. 3.47.

- Phillips, Stephen (July 16, 1993). "Conrail Sells Land for Marina on the Lake". The Plain Dealer. p. E1.

- Lubinger, Bill (March 5, 1999). "Whiskey Island Land for Sale". The Plain Dealer. p. C1.

- Mazzolini, Joan (December 15, 2004). "County to buy Whiskey Island". The Plain Dealer. p. B1.

- Hollander, Sarah; Mazzolini, Joan (July 21, 2005). "County, city agree on future of island". The Plain Dealer. p. B1.

- Lewis 1996, p. 16.

- "Ohio county seeks STB approval to acquire privately held line". Progressive Railroading. March 22, 2004. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- Eastgate Regional Council of Governments (April 2013). The 2040 Metropolitan Transportation Plan (PDF) (Report). Columbus, Ohio. p. 239. Retrieved November 20, 2017; Surface Transportation Board, Department of Transportation. STB Finance Docket No. 32798. "Economic Development Rail II Corporation—Acquisition Exemption—Lines of Consolidated Rail Corporation." 61 FR 16528. April 15, 1996.

- Surface Transportation Board, Department of Transportation. STB Finance Docket No. 33012. "Warren & Trumbull Railroad Company—Acquisition Exemption—Lines of Consolidated Rail Corporation." 61 FR 42084. August 13, 1996.

- Surface Transportation Board, Department of Transportation. STB Finance Docket No. 33332. "Summit View Incorporated—Continuance in Control Exemption—The Youngstown Belt Railroad Company." 62 FR 3735. January 24, 1997.

- Miller, Jay (February 7, 2011). "Cleveland railroad quietly, quickly moves on expansion projects". Crain's Cleveland Business. Retrieved September 5, 2017; Schoenberger, Robert (January 24, 2011). "Railroad operator finds a half mile of track, plans to service steel companies". Crain's Cleveland Business. Retrieved September 5, 2017; "Cleveland Commercial Railroad" (PDF). The Railroad Week in Review. June 12, 2009. p. 2. Retrieved September 5, 2017.

- "AB-290 (Sub-No. 394X). Norfolk Southern Railway Company Proposed Abandonment. AB-1257. Cleveland Commercial Railroad Company, LLC Discontinuance of Lease and Operation Authority Between Milepost RH 22.0 and Milepost RH 27.5 in Aurora, Ohio" (PDF). Surface Transportation Board. U.S. Department of Transportation. June 23, 2017. p. 2. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Erie Railroad Company 1918, p. 20.

- Erie Magazine 1958, p. 14.

- Erie Magazine 1958, p. 15-16.

- Erie Magazine 1958, p. 16.

- Erie Magazine 1958, p. 17.

- Kawa, Barry (August 25, 1997). "The Gift of Life: Family Gives for Hiking Trail". The Plain Dealer. p. B1.

- Oblander, Terry (June 4, 1998). "State Grants to Fund Improvements, Parks in Six Summit Communities". The Plain Dealer. p. B1.

- "Where Nature Dresses for its Big Autumn Show". The Plain Dealer. September 1, 2000. p. E1.

- Sever, Mike (February 7, 2003). "Park district buying old rail land". Record-Courier. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- "Headwaters Trail expansion to get $60,000 from state". Record-Courier. November 6, 2017. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- "AB-290 (Sub-No. 394X). Norfolk Southern Railway Company Proposed Abandonment. AB-1257. Cleveland Commercial Railroad Company, LLC Discontinuance of Lease and Operation Authority Between Milepost RH 22.0 and Milepost RH 27.5 in Aurora, Ohio" (PDF). Surface Transportation Board. U.S. Department of Transportation. June 23, 2017. p. 23. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Turner, Stacy (January 13, 2017). "News from Mantua Village". Weekly Villager. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- Muhs, Angie (July 31, 1989). "RiverFest Rolls Right Along Despite Gray Skies". The Plain Dealer. p. B2.

- Lesie, Michele (March 17, 1989). "Burying a Bad Image". The Plain Dealer. p. B16.

- Thomas, Pauline (April 21, 1992). "Study Recommends Valley Rail Extension, Trails". The Plain Dealer. p. B2.

- Litt, Steven (January 10, 2009). "Plan designed to link gray Flats to green future". The Plain Dealer. p. A1. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- Litt, Steven (December 29, 2009). "Land purchase moves trail plan a step closer to Lake Erie shore". The Plain Dealer. p. A1. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- Ewinger, James (August 20, 2014). "Gift will help close trail's final gap". The Plain Dealer. pp. A1, A3.

- Litt, Steven (June 9, 2016). "NOACA poised to approve vital grant to plan future of Irishtown Bend". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved November 26, 2017.

- McCarty, James F. (August 14, 2015). "Interior secretary joins ceremony dedicating Centennial Trail's first leg". The Plain Dealer. p. A12.

- Litt, Steven (June 7, 2017). "Newest section of Lake Link Trail is set to open Friday". The Plain Dealer. p. A1. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- Rice, Karen Connelly (June 20, 2017). "New Lake Link Trail segment unveils a wonderland in the Flats". Freshwater Cleveland. Retrieved November 24, 2017.

- Litt, Steven (October 28, 2017). "West Side greenway trail gets final funds". The Plain Dealer. p. A1.

Bibliography

- Albert, Albert George (1882). History of the County of Westmoreland, Pennsylvania, With Biographical Sketches of Many of Its Pioneers and Prominent Men. Philadelphia: L.H. Everts & Co.

- Avery, Elroy McKendree (1918). A History of Cleveland and Its Environs: The Heart of New Connecticut. Volume 2. Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co.

- Barr and Prevost (May 1, 2015). Final Report: Franklin Hill/Irishtown Bend Stabilization and Restoration (Report). Cleveland. Retrieved November 28, 2017.

- Bianculli, Anthony J. (2003). Trains and Technology: The American Railroad in the Nineteenth Century. Volume 4: Bridges and Tunnels; Signals. Newark, Del.: University of Delaware Press. ISBN 9780874138030.

- Brown, R.C.; Norris, J.E. (1885). History of Portage County, Ohio. Chicago: Warner, Beers & Co.

- Butler, Joseph G., Jr. (1921). History of Youngstown and the Mahoning Valley, Ohio. Volume 1. Chicago: American Historical Society.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Camp, Mark J. (2007). Railroad Depots of Northeast Ohio. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738551159.

- Churella, Albert J. (2013). The Pennsylvania Railroad. Volume 1: Building an Empire, 1846-1917. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812243482.

- Comley, W.J.; D'Eggville, W. (1875). Ohio, the Future Great State, Her Manufacturers, and a History of Her Commercial Cities, Cincinnati and Cleveland. Cincinnati: Comley Bros.

- Ellenberger, J.S.; Mahar, Ellen P. (1973). Legislative History of the Securities Act of 1933 and Securities Exchange Act of 1934. South Hackensack, N.J.: Law Librarians' Society of Washington, D.C.

- "Erie's Mahoning Branches Serve Three Basic Industries" (PDF). Erie Magazine. March 1959. pp. 12–15, 27–28. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- "Erie's Mahoning Division Is Nation's Ore, Steel Handler" (PDF). Erie Magazine. November 1958. pp. 12–15, 26–29. Retrieved November 19, 2017.

- Erie Railroad Company (1888). Report of the Board of Directors of New York, Lake Erie, and Western Railroad Company to the Bond and Shareholders for the Year Ending September 30, 1888 (Report). New York: New York, Lake Erie, and Western Railroad Company.

- Erie Railroad Company (1899). Report of the Board of Directors of New York, Lake Erie, and Western Railroad Company to the Bond and Shareholders for the Year Ending September 30, 1899 (Report). New York: New York, Lake Erie, and Western Railroad Company.

- Erie Railroad Company (1918). Report of the Board of Directors of the Erie Railroad Company to the Bond and Shareholders for the Year Ending December 31, 1917 (Report). New York: Erie Railroad Company. hdl:2027/osu.32435067090118.

- Finkelman, Paul, ed. (2001). Encyclopedia of the United States in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Scribner. ISBN 9780684805009.

- Grant, H. Roger (2001). Erie Lackawanna: The Death of an American Railroad, 1938-1992. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804727983.

- Harwood, Herbert H. (2003). Invisible Giants: The Empires of Cleveland's Van Sweringen Brothers. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253341631.

- History of Mercer County, Pennsylvania: Its Past and Present. Chicago: Brown, Runk & Co. 1888.

- History of Trumbull and Mahoning Counties. Volume 1. Cleveland: H.Z. Williams & Bro. 1882.

- Holm, James B.; Dudley, Lucille (1957). Portage Heritage: A History of Portage County, Ohio; Its Towns and Townships and the Men and Women Who Have Developed Them; Its Life, Institutions and Biographies, Facts and Lore. Ravenna, Ohio: Commercial Press Incorporated.

- Interstate Commerce Commission (1931). Decisions of the Interstate Commerce Commission of the United States, June-December 1930. Interstate Commerce Commission Reports. Volume 33: Valuation Reports (Report). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office. hdl:2027/uc1.b2963282.

- Jordan, John W. (1911). Colonial and Revolutionary Families of Pennsylvania: Genealogical and Personal Memoirs. Baltimore: The Lewis Publishing Co. hdl:2027/coo.31924092226806.

- Kennedy, James Harrison (October 1885). The Early Railroad Interests of Cleveland. pp. 594–619.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Kennedy, James Harrison (1896). A History of the City of Cleveland: Its Settlement, Rise, and Progress, 1796-1896. Cleveland: The Imperial Press.

- Leading Manufacturers and Merchants of the City of Cleveland and Environs: A Half Century's Progress. Boston: International Publishing Co. 1886.

- Lewis, Edward A. (1996). American Shortline Railway Guide. Waukesha, Wisc.: Kalmbach Publishing Co. ISBN 9780890242902.

- MacKeigan, Judith A. (May 2011). "The Good People of Newburgh": Yankee Identity and Industrialization in a Cleveland Neighborhood, 1850-1992 (MA). Cleveland State University. Retrieved July 18, 2017.

- "Mahoning Division Carries Steel Industry's Life-Blood" (PDF). Erie Magazine. December 1958. pp. 12–17. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- Miller, Richard F., ed. (2015). States at War. Volume 5: A Reference Guide for Ohio in the Civil War. Lebanon, N.H.: University Press of New England. ISBN 9781611683240.

- Moody, John (1922). Moody's Manual of Investments and Security Rating Books. New York: Moody's Investors Service.

- Morris, Charles R. (2006). The Tycoons: How Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller, Jay Gould, and J.P. Morgan Invented the American Supereconomy. New York: Owl Books. ISBN 9780805081343.