Cleitus the Black

Cleitus the Black (Greek: Κλεῖτος ὁ μέλας; c. 375 BC – 328 BC) was an officer of the Macedonian army led by Alexander the Great. He saved Alexander's life at the Battle of the Granicus in 334 BC and was killed by him in a drunken quarrel six years later.[1][2][3] Cleitus was the son of Dropidas (who was the son of Critias) and brother of Alexander's nurse, Lanike.[4][5][6] He would be given the epithet 'the Black' to distinguish him from Cleitus the White.[7]

Cleitus the Black | |

|---|---|

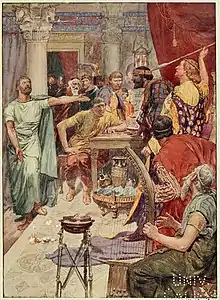

_reduced.jpg.webp) Alexander kills Cleitus, André Castaigne, c. 1898–1899 | |

| Native name | Κλεῖτος ὁ μέλας |

| Birth name | Cleitus |

| Born | 375 BC |

| Died | 328 BC (aged 46–47 years old) Markanda, Bactria |

| Allegiance | Macedonia |

| Commands held | Companion cavalry |

| Battles/wars | Wars of Alexander the Great |

| Relations | Lanike (sister), Critias (grandfather) |

Military service

Cleitus was made a commander of the Greek Cavalry under Philip II, a position he would retain under Alexander the Great.[8]

At the Battle of the Granicus in 334 BC, when Alexander was being assailed by both Rhosaces and Spithridates, Cleitus severed Spithridates's arm before the Persian satrap could bring it down on Alexander, thus saving his life.[8][9][10]

He would later be promoted to one of the two commanders of the companion cavalry following the trial and execution of Philotas.[5][6][7]

The death of Cleitus

In 328 BC, Artabazos resigned his satrapy of Bactria, and Alexander gave it to Cleitus.[8][11] On the eve of the day on which he was to set out to take possessions of his government, Alexander organized a banquet during a feast day for Dionysus in the satrapial palace at Maracanda (what is now the town of Samarkand).[6] At this banquet an angry dispute arose, the particulars of which are disputed by various authors.

Most of the members were rather drunk, and Alexander announced a reorganization of commands. Specifically, Cleitus was given orders to take 16,000 of the defeated Greek mercenaries who formerly fought for the Persian King north to fight the steppe nomads in Central Asia.

Cleitus knew that he would no longer be near the king and would be a forgotten man. Furious at the thought of commanding what he saw as second-rate soldiers and fighting nomads in the middle of nowhere, he spoke his mind. To make matters worse, when Alexander arrogantly boasted that his accomplishments were far greater than that of his father, Phillip II, Cleitus responded by saying that Alexander was not the legitimate king of the Macedonians, and that all of his achievements were due to his father.[12] Alexander called for his guards, but they did not want to intervene in a quarrel between friends.

Alexander threw an apple at Cleitus' head and called for a dagger or spear, but the party near the two men removed the dagger, restrained Alexander, and hustled Cleitus out of the room. The Hypaspists had conveniently left the vicinity of Alexander. Alexander then called for his trumpeter to summon the army; the alarm was not sounded. Nevertheless, Cleitus managed to return to the room to utter more grievances against Alexander (it is possible that Cleitus had not even left the room). But sources agree that at this point Alexander got hold of a javelin and threw it through Cleitus's heart.[2][5][7]

In all of the four major known texts, it is shown that Alexander grieved for the death of Cleitus.[6] Alexander may have genuinely not wanted to kill Cleitus. However, Cleitus was a member of Philip II's generation and Alexander had been removing that generation from power to keep his own peers in power.

The motives of Cleitus in this quarrel have been interpreted in various ways. Cleitus may have been angered at Alexander's increasing adoption of Persian customs. After the death of King Darius III, Alexander was legally King of the Persian Empire. Alexander was now employing eunuchs and was tolerant of such Persian customs as proskynesis, which was considered degrading by many in the Macedonian army.[3]

Cultural references

Cleitus, as Clito, appears as a character in Handel's opera Alessandro.

The American poet John Berryman recounts the tale of "Kleitos" in his thirty-third "dream song."

Cleitus, played by Gary Stretch, is a supporting character in the film Alexander. His death scene in the film is consistent with the historical sources.

Cleitus' death is also described in Mary Butts' 1931 novel The Macedonian.

Cleitus' story is recalled in Henry V in comparing Sir John Falstaff and King Henry V to Cleitus and Alexander in Act IV Scene 7 Lines 33–50.[13]

Seneca the Younger makes a reference to Cleitus' death in letter 83 of his book Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium.[14]

References

- James S. Romm (2011). Ghost on the Throne: The Death of Alexander the Great and the War for Crown and Empire. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-307-27164-8.

- Sanchez, Juan Pablo (September 27, 2018). "How suspicion and intrigue eroded Alexander's empire". History Magazine. National Geographic. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- Hanson, Victor Davis (2007-12-18). Carnage and Culture: Landmark Battles in the Rise to Western Power. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-42518-8.

- Rockefeller, J. D. (2016-11-22). The Story of Alexander the Great. J.D. Rockefeller.

- Grote, George (1907). A History of Greece: From the Earliest Period to the Close of the Generation Contemporary with Alexander the Great. John Murray.

- Skelton, Debra; Dell, Pamela (2009). Empire of Alexander the Great. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-60413-162-8.

- Chrystal, Paul (2016-05-15). In Bed with the Ancient Greeks. Amberley Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-4456-5413-3.

- Mothe, Gordon De la (1993). Reconstructing the Black Image. Trentham Books. ISBN 978-0-948080-61-6.

- Arrian, Anabasis Alexandri, i. 12, 15, 16

- Plutarch, The Life of Alexander, 16.

- Smith, William (editor); Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, "Cleitus (2)", Boston, (1867), p. 785.

- Gabriel, Richard A. (2015-03-31). The Madness of Alexander the Great: And the Myth of Military Genius. Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-5236-5.

- Henry V 4.7/33–50, Folger Shakespeare Library

- Seneca, Lucius Annaeus. "Epistulae Morales ad Lucilium". Internet Archive. p. 270. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

External links

- Plutarch, The Life of Alexander, 16 and 50–51.

- Livius, Clitus by Jona Lendering