Cocoa bean

The cocoa bean (technically cocoa seed) or simply cocoa (/ˈkoʊ.koʊ/), also called cacao (/kəˈkaʊ/),[1] is the dried and fully fermented seed of Theobroma cacao, from which cocoa solids (a mixture of nonfat substances) and cocoa butter (the fat) can be extracted. Cocoa beans native to the Amazon rainforest are the basis of chocolate, and Mesoamerican foods including tejate, an indigenous Mexican drink.

The cacao tree, native to the Amazon rainforest, was first domesticated 5,300 years ago in South America before being introduced to Central America by the Olmecs. Cacao was consumed by pre-Hispanic cultures in spiritual ceremonies and its beans were a common currency in Mesoamerica. The cacao tree grows in a limited geographical zone, and today, West Africa produces nearly 81% of the world's crop. The three main varieties of cocoa plant are Forastero, Criollo, and Trinitario, with Forastero being the most widely used.

In 2020, global cocoa bean production reached 5.8 million tonnes, with Ivory Coast leading at 38% of the total, followed by Ghana and Indonesia. Cocoa beans, cocoa butter, and cocoa powder are traded on futures markets, with London focusing on West African cocoa and New York on Southeast Asian cocoa. Various international and national initiatives aim to support sustainable cocoa production, including the Swiss Platform for Sustainable Cocoa (SWISSCO), the German Initiative on Sustainable Cocoa (GISCO), and Beyond Chocolate, Belgium. At least 29% of global cocoa production was compliant with voluntary sustainability standards in 2016. Deforestation due to cocoa production remains a concern, especially in West Africa. Sustainable agricultural practices, such as agroforestry, can support cocoa production while conserving biodiversity. Cocoa contributes significantly to economies like Nigeria, and demand for cocoa products continues to grow steadily at over 3% annually since 2008.

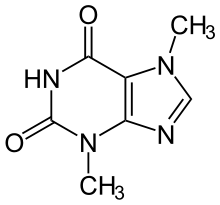

To produce 1 kg/2.2 pounds of chocolate, around 300 to 600 cocoa beans are processed. The beans are roasted, cracked, and deshelled, resulting in pieces called nibs, which are ground into a thick paste known as chocolate liquor or cocoa paste. The liquor is processed into chocolate by adding cocoa butter, sugar, and sometimes vanilla and lecithin. Alternatively, cocoa powder and cocoa butter can be separated using a hydraulic press or the Broma process. Treating cocoa with an alkali produces Dutch process cocoa, which has a different flavor profile than untreated cocoa. Roasting can also be done on the whole bean or nib, affecting the final flavor. Cocoa contains phytochemicals like flavanols, procyanidins, and other flavonoids, and flavanol-rich chocolate and cocoa products may have a small blood pressure lowering effect. The beans also contain theobromine and a small amount of caffeine.

Etymology

The word cocoa comes from the Spanish word cacao, which is derived from the Nahuatl word cacauatl.[2][3] The Nahuatl word, in turn, ultimately derives from the reconstructed Proto-Mixe–Zoquean word kakawa.[4]

(The reason for the inversion of the letters "o" and "a" in the borrowing from the Spanish "cacao" to the English "cocoa" is unknown, but etymological dictionaries speculate that it originated with a simple isolated arbitrary spelling confusion during the borrowing, possibly due to influence from the unrelated Spanish word "coco", but does not appear to represent any larger linguistic pattern or have any particular obvious motivation beyond that, neither semantic nor euphonic.[5])

Used on its own, the term cocoa may also mean:

- Hot cocoa, the drink more known as hot chocolate[6]

Terms derived from cocoa include:

- Cocoa paste, ground cocoa beans:[7] the mass is melted and separated into:

- Cocoa butter, a pale, yellow, edible fat

- Cocoa solids, the dark, bitter mass that contain most of cacao's notable phytochemicals, including caffeine and theobromine

- Cocoa powder, a powder made by removing most of the cocoa butter from ground cacao seeds, or its derivatives, such as Dutch process cocoa

Cocoa beans are technically not beans or legumes, but seeds.[8]

History

The cacao tree is native to the Amazon rainforest. It was first domesticated 5,300 years ago, in equatorial South America, before being introduced in Central America by the Olmecs (Mexico). More than 4,000 years ago, it was consumed by pre-Hispanic cultures along the Yucatán, including the Maya, and as far back as Olmeca civilization in spiritual ceremonies. It also grows in the foothills of the Andes in the Amazon and Orinoco basins of South America, in Colombia and Venezuela. Wild cacao still grows there. Its range may have been larger in the past; evidence of its wild range may be obscured by cultivation of the tree in these areas since long before the Spanish arrived.

As of November 2018, evidence suggests that cacao was first domesticated in equatorial South America,[9] before being domesticated in Central America roughly 1,500 years later.[10] Artifacts found at Santa-Ana-La Florida, in Ecuador, indicate that the Mayo-Chinchipe people were cultivating cacao as long as 5,300 years ago.[10] Chemical analysis of residue extracted from pottery excavated at an archaeological site at Puerto Escondido, in Honduras, indicates that cocoa products were first consumed there sometime between 1500 and 1400 BC. Evidence also indicates that, long before the flavor of the cacao seed (or bean) became popular, the sweet pulp of the chocolate fruit, used in making a fermented (5.34% alcohol) beverage, first drew attention to the plant in the Americas.[11] The cocoa bean was a common currency throughout Mesoamerica before the Spanish conquest.[12]: 2

Cacao trees grow in a limited geographical zone, of about 20° to the north and south of the Equator. Nearly 70% of the world crop today is grown in West Africa. The cacao plant was first given its botanical name by Swedish natural scientist Carl Linnaeus in his original classification of the plant kingdom, where he called it Theobroma ("food of the gods") cacao.

Cocoa was an important commodity in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica.[13] A Spanish soldier who was on Hernan Cortés' side during the conquest of the Aztec Empire tells that when Moctezuma II, emperor of the Aztecs, dined, he took no other beverage than chocolate, served in a golden goblet. Flavored with vanilla or other spices, his chocolate was whipped into a froth that dissolved in the mouth. No fewer than 60 portions each day reportedly may have been consumed by Moctezuma II, and 2,000 more by the nobles of his court.[14]

Chocolate was introduced to Europe by the Spaniards, and became a popular beverage by the mid-17th century.[15] Spaniards also introduced the cacao tree into the West Indies and the Philippines.[16] It was also introduced into the rest of Asia, South Asia and into West Africa by Europeans. In the Gold Coast, modern Ghana, cacao was introduced by a Ghanaian, Tetteh Quarshie.

Varieties

The three main varieties of cocoa plant are Forastero, Criollo, and Trinitario. The first is the most widely used, comprising 80–90% of the world production of cocoa. Cocoa beans of the Criollo variety are rarer and considered a delicacy.[17][18] Criollo also tends to be less resistant to several diseases that attack the cocoa plant, hence very few countries still produce it. One of the largest producers of Criollo beans is Venezuela (Chuao and Porcelana). Trinitario (from Trinidad) is a hybrid between Criollo and Forastero varieties. It is considered to be of much higher quality than Forastero, has higher yields, and is more resistant to disease than Criollo.[18]

Criollo

Representing only 5% of all cocoa beans grown as of 2008,[19] Criollo is the rarest and most expensive cocoa on the market, and is native to Central America, the Caribbean islands and the northern tier of South American states.[20] The genetic purity of cocoas sold today as Criollo is disputed, as most populations have been exposed to the genetic influence of other varieties.

Criollo is particularly difficult to grow, as they are vulnerable to a variety of environmental threats and produce low yields of cocoa per tree. The flavor of Criollo is described as delicate yet complex, low in classic chocolate flavor, but rich in "secondary" notes of long duration.[21]

Forastero

The most commonly grown bean is Forastero,[19] a large group of wild and cultivated cocoas, most likely native to the Amazon Basin. The African cocoa crop is entirely made up of Forastero. They are significantly hardier and of higher yield than Criollo. The source of most chocolate marketed,[19] Forastero cocoas are typically strong in classic "chocolate" flavor, but have a short duration and are unsupported by secondary flavors, producing "quite bland" chocolate.[19] Forastero is particularly tannic and is therefore more astringent and bitter than the other varieties of cocoa.[22]

Nacional

The Nacional is a rare variety of cocoa bean found in areas of South America such as Ecuador and Peru.[23][24] Some experts in the 21st century had formerly considered the Nacional bean to be extinct after an abrupt end in 1916, when an outbreak of witch's broom disease devastated the Nacional variety throughout these countries.[24] Pure genotypes of the bean are rare because most Nacional varieties have been interbred with other cocoa bean varieties.[25] Ecuadorian Nacional traces its genetic lineage as far back as 5,300 years, to the earliest-known cacao trees domesticated by humanity. In the 18th and 19th centuries, Nacional was considered by many European chocolatiers to be the most coveted source of cacao in the world due to its floral aroma and complex flavor profile.

Trinitario

Trinitario is a natural hybrid of Criollo and Forastero. Trinitario originated in Trinidad after an introduction of Forastero to the local Criollo crop. Nearly all cocoa produced over the past five decades is of the Forastero or lower-grade Trinitario varieties.[26]

Cultivation

A cocoa pod (fruit) is about 17 to 20 cm (6.7 to 7.9 in) long and has a rough, leathery rind about 2 to 3 cm (0.79 to 1.18 in) thick (this varies with the origin and variety of pod) filled with sweet, mucilaginous pulp (called baba de cacao in South America) with a lemonade-like taste enclosing 30 to 50 large seeds that are fairly soft and a pale lavender to dark brownish purple color.

During harvest, the pods are opened, the seeds are kept, and the empty pods are discarded and the pulp made into juice. The seeds are placed where they can ferment. Due to heat buildup in the fermentation process, cacao beans lose most of the purplish hue and become mostly brown in color, with an adhered skin which includes the dried remains of the fruity pulp. This skin is released easily by winnowing after roasting. White seeds are found in some rare varieties, usually mixed with purples, and are considered of higher value.[27][28]

Harvesting

Cocoa trees grow in hot, rainy tropical areas within 20° of latitude from the Equator. Cocoa harvest is not restricted to one period per year and a harvest typically occurs over several months. In fact, in many countries, cocoa can be harvested at any time of the year.[12] Pesticides are often applied to the trees to combat capsid bugs, and fungicides to fight black pod disease.[29]

Immature cocoa pods have a variety of colours, but most often are green, red, or purple, and as they mature, their colour tends towards yellow or orange, particularly in the creases.[12][30] Unlike most fruiting trees, the cacao pod grows directly from the trunk or large branch of a tree rather than from the end of a branch, similar to jackfruit. This makes harvesting by hand easier as most of the pods will not be up in the higher branches. The pods on a tree do not ripen together; harvesting needs to be done periodically through the year.[12] Harvesting occurs between three and four times weekly during the harvest season.[12] The ripe and near-ripe pods, as judged by their colour, are harvested from the trunk and branches of the cocoa tree with a curved knife on a long pole. Care must be used when cutting the stem of the pod to avoid damaging the junction of the stem with the tree, as this is where future flowers and pods will emerge.[12][31] One person can harvest an estimated 650 pods per day.[29][32]

Harvest processing

The harvested pods are opened, typically with a machete, to expose the beans.[12][29] The pulp and cocoa seeds are removed and the rind is discarded. The pulp and seeds are then piled in heaps, placed in bins, or laid out on grates for several days. During this time, the seeds and pulp undergo "sweating", where the thick pulp liquefies as it ferments. The fermented pulp trickles away, leaving cocoa seeds behind to be collected. Sweating is important for the quality of the beans,[33] which originally have a strong, bitter taste. If sweating is interrupted, the resulting cocoa may be ruined; if underdone, the cocoa seed maintains a flavor similar to raw potatoes and becomes susceptible to mildew. Some cocoa-producing countries distill alcoholic spirits using the liquefied pulp.[34]

A typical pod contains 30 to 40 beans and about 400 dried beans are required to make 1 pound (450 g) of chocolate. Cocoa pods weigh an average of 400 g (14 oz) and each one yields 35 to 40 g (1.2 to 1.4 oz) dried beans; this yield is 9–10% of the total weight in the pod.[29] One person can separate the beans from about 2000 pods per day.[29][32]

.jpg.webp)

The wet beans are then transported to a facility so they can be fermented and dried.[29][32] The farmer removes the beans from the pods, packs them into boxes or heaps them into piles, then covers them with mats or banana leaves for three to seven days.[35] Finally, the beans are trodden and shuffled about (often using bare human feet) and sometimes, during this process, red clay mixed with water is sprinkled over the beans to obtain a finer color, polish, and protection against molds during shipment to factories in other countries. Drying in the sun is preferable to drying by artificial means, as no extraneous flavors such as smoke or oil are introduced which might otherwise taint the flavor.

The beans should be dry for shipment, which is usually by sea. Traditionally exported in jute bags, over the last decade, beans are increasingly shipped in "mega-bulk" parcels of several thousand tonnes at a time on ships, or standardized to 62.5 kilograms (138 lb) per bag and 200 (12.5 metric tons (12.3 long tons; 13.8 short tons)) or 240 (15 metric tons (15 long tons; 17 short tons)) bags per 20 feet (6.1 m) container. Shipping in bulk significantly reduces handling costs. Shipment in bags, either in a ship's hold or in containers, is still common.

Throughout Mesoamerica where they are native, cocoa beans are used for a variety of foods. The harvested and fermented beans may be ground to order at tiendas de chocolate, or chocolate mills. At these mills, the cocoa can be mixed with a variety of ingredients such as cinnamon, chili peppers, almonds, vanilla, and other spices to create drinking chocolate.[36] The ground cocoa is also an important ingredient in tejate.

Child slavery

The first allegations that child slavery is used in cocoa production appeared in 1998.[37] In late 2000, a BBC documentary reported the use of enslaved children in the production of cocoa in West Africa.[37][38][39] Other media followed by reporting widespread child slavery and child trafficking in the production of cocoa.[40][41]

The cocoa industry was accused of profiting from child slavery and trafficking.[42] The Harkin–Engel Protocol is an effort to end these practices.[43] In 2001, it was signed and witnessed by the heads of eight major chocolate companies, US senators Tom Harkin and Herb Kohl, US Representative Eliot Engel, the ambassador of the Ivory Coast, the director of the International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labor, and others.[43] It has, however, been criticized by some groups including the International Labor Rights Forum as an industry initiative which falls short, as the goal to eliminate the "worst forms of child labor" from cocoa production by 2005 was not reached.[44][45][46][47] The deadline was extended multiple times and the goal changed to a 70% child labor reduction.[48][49]

Child labour was growing in some West African countries in 2008–09 when it was estimated that 819,921 children worked on cocoa farms in Ivory Coast alone; by 2013–14, the number went up to 1,303,009. During the same period in Ghana, the estimated number of children working on cocoa farms was 957,398 children.[50]

The 2010 documentary The Dark Side of Chocolate revealed that children smuggled from Mali to the Ivory Coast were forced to earn income for their parents, while others were sold as slaves for €230.

In 2010, the US Department of Labor formed the Child Labor Cocoa Coordinating Group as a public-private partnership with the governments of Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire to address child labor practices in the cocoa industry.[51]

As of 2017, approximately 2.1 million children in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire were involved in harvesting cocoa, carrying heavy loads, clearing forests, and being exposed to pesticides.[52] According to Sona Ebai, the former secretary general of the Alliance of Cocoa Producing Countries: "I think child labor cannot be just the responsibility of industry to solve. I think it's the proverbial all-hands-on-deck: government, civil society, the private sector. And there, you really need leadership."[53] As Reported in 2018, a 3-year pilot program, conducted by Nestlé with 26,000 farmers mostly located in Côte d'Ivoire, observed a 51% decrease in the number of children doing hazardous jobs in cocoa farming.[54]

Lawsuits

In 2021, several companies were named in a class action lawsuit filed by eight former children from Mali who alleged that the companies aided and abetted their enslavement on cocoa plantations in Ivory Coast. The suit accused Barry Callebaut, Cargill, The Hershey Company, Mars, Mondelez, Nestlé, and Olam International, of knowingly engaging in forced labour, and the plaintiffs sought damages for unjust enrichment, negligent supervision, and intentional infliction of emotional distress.[55]

Production

| Country | Weight (tonnes) |

|---|---|

| 2,200,000 | |

| 800,000 | |

| 739,483 | |

| 340,163 | |

| 327,903 | |

| 290,000 | |

| 269,731 | |

| World | 5,756,953 |

In 2020, world production of cocoa beans was 5.8 million tonnes, led by Ivory Coast with 38% of the total. Secondary producers were Ghana and Indonesia (each with about 14%).[56]

Cocoa trading

Cocoa beans are traditionally shipped and stored in burlap sacks, in which the beans are susceptible to pest attacks.[57] Fumigation with methyl bromide was to be phased out globally by 2015. Additional cocoa protection techniques for shipping and storage include the application of pyrenoids as well as hermetic storage in sealed bags or containers with lowered oxygen concentrations.[58] Safe long-term storage facilitates the trading of cocoa products at commodity exchanges.

Cocoa beans, cocoa butter and cocoa powder are traded on futures markets. The London market is based on West African cocoa and New York on cocoa predominantly from Southeast Asia. Cocoa is the world's smallest soft commodity market. The futures price of cocoa butter and cocoa powder is determined by multiplying the bean price by a ratio. The combined butter and powder ratio has tended to be around 3.5. If the combined ratio falls below 3.2 or so, production ceases to be economically viable and some factories cease extraction of butter and powder and trade exclusively in cocoa liquor.

Cocoa futures traded on the ICE Futures US Softs exchange, are valued at 10 Tonnes per contract with a tick size of 1 and tick value of US$10.[59]

| Cocoa (CCA) | |

|---|---|

| Exchange: | NYI |

| Sector: | Soft |

| Tick Size: | 1 |

| Tick Value: | 10 USD |

| BPV: | 10 |

| Denomination: | USD |

| Decimal Place: | 0 |

Sustainability

Multiple international and national initiatives collaborate to support sustainable cocoa production. These include the Swiss Platform for Sustainable Cocoa (SWISSCO), the German Initiative on Sustainable Cocoa (GISCO), and Beyond Chocolate, Belgium. A memorandum between these three initiatives was signed in 2020 to measure and address issues including child labor, living income, deforestation and supply chain transparency.[60] Similar partnerships between cocoa producing and consuming countries are being developed, such as the cooperation between the International Cocoa Organization (ICCO) and the Ghanaian Cocoa Authority, who aim to increase the proportion of sustainable cocoa being imported from Ghana to Switzerland to 80% by 2025.[61] The ICCO is engaged in projects around the world to support sustainable cocoa production and provide current information on the world cocoa market.[62]

Voluntary sustainability standards

There are numerous voluntary certifications including Fairtrade and UTZ (now part of Rainforest Alliance) for cocoa which aim to differentiate between conventional cocoa production and that which is more sustainable in terms of social, economic and environmental concerns. As of 2016, at least 29% of global cocoa production was compliant with voluntary sustainability standards.[63] However, among the different certifications there are significant differences in their goals and approaches, and a lack of data to show and compare the results on the farm level. While certifications can lead to increased farm income, the premium price paid for certified cocoa by consumers is not always reflected proportionally in the income for farmers. In 2012 the ICCO found that farm size mattered significantly when determining the benefits of certifications, and that farms an area less than 1ha were less likely to benefit from such programs, while those with slightly larger farms as well as access to member co-ops and the ability to improve productivity were most likely to benefit from certification.[64] Certification often requires high up-front costs, which are a barrier to small farmers, and particularly, female farmers. The primary benefits to certification include improving conservation practices and reducing the use of agrochemicals, business support through cooperatives and resource sharing, and a higher price for cocoa beans which can improve the standard of living for farmers.[65]

Fair trade cocoa producer groups are established in Belize, Bolivia, Cameroon, the Congo,[66] Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic,[67] Ecuador, Ghana, Haiti, India, Ivory Coast, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Sierra Leone, and São Tomé and Príncipe.

In 2018, the Beyond Chocolate partnership was created between multiple stakeholders in the global cocoa industry to decrease deforestation and provide a living income for cocoa farmers. The many international companies are currently participating in this agreement and the following voluntary certification programs are also partners in the Beyond Chocolate initiative: Rainforest Alliance, Fairtrade, ISEAL, BioForum Vlaanderen.[68]

Many major chocolate production companies around the world have started to prioritize buying fair trade cocoa by investing in fair trade cocoa production, improving fair trade cocoa supply chains and setting purchasing goals to increase the proportion of fair trade chocolate available in the global market.[69][70][71][72][73]

The Rainforest Alliance lists the following goals as part of their certification program:

- Forest protection and sustainable land management

- Improve rural livelihoods to reduce poverty

- Address human rights issues such as child labor, gender inequality and indigenous land rights

The UTZ Certified-program (now part of Rainforest Alliance) included counteracting against child labor and exploitation of cocoa workers, requiring a code of conduct in relation to social and environmentally friendly factors, and improvement of farming methods to increase profits and salaries of farmers and distributors.[74]

Environmental impact

The relative poverty of many cocoa farmers means that environmental consequences such as deforestation are given little significance. For decades, cocoa farmers have encroached on virgin forest, mostly after the felling of trees by logging companies. This trend has decreased as many governments and communities are beginning to protect their remaining forested zones.[75] However, deforestation due to cocoa production is still a major concern in parts of West Africa. In Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana, barriers to land ownership have led migrant workers and farmers without financial resources to buy land to illegally expand their cocoa farming in protected forests. Many cocoa farmers in this region continue to prioritize expansion of their cocoa production, which often leads to deforestation.[76]

Sustainable agricultural practices such as utilizing cover crops to prepare the soil before planting and intercropping cocoa seedlings with companion plants can support cocoa production and benefit the farm ecosystem. Prior to planting cocoa, leguminous cover crops can improve the soil nutrients and structure, which are important in areas where cocoa is produced due to high heat and rainfall which can diminish soil quality. Plantains are often intercropped with cocoa to provide shade to young seedlings and improve drought resilience of the soil. If the soil lacks essential nutrients, compost or animal manure can improve soil fertility and help with water retention.[77]

In general, the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides by cocoa farmers is limited. When cocoa bean prices are high, farmers may invest in their crops, leading to higher yields which, in turn tends to result in lower market prices and a renewed period of lower investment.

While governments and NGOs have made efforts to help cocoa farmers in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire sustainably improve crop yields, many of the educational and financial resources provided are more readily available to male farmers versus female farmers. Access to credit is important for cocoa farmers, as it allows them to implement sustainable practices, such as agroforestry, and provide a financial buffer in case disasters like pest or weather patterns decrease crop yield.[76]

Cocoa production is likely to be affected in various ways by the expected effects of global warming. Specific concerns have been raised concerning its future as a cash crop in West Africa, the current centre of global cocoa production. If temperatures continue to rise, West Africa could simply become unfit to grow the beans.[78][79] The International Center for Tropical Agriculture warned in a paper published in 2013 that Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire, the world's two top cocoa growers, will experience a decline in suitable areas for cocoa production as global temperatures rise by up to 2 °C by 2050.[80]

Climate change, coupled with pests, poor soil health, and the demand for sustainable cocoa, has led to a rapid decline in cocoa productivity, resulting in reduced income for smallholder cocoa farmers.[81] Severe droughts have led to soil fertility decline, causing a decrease in yields, and resulting in some farmers abandoning cocoa production.[82][83]

Cocoa beans also have a potential to be used as a bedding material in farms for cows. Using cocoa bean husks in bedding material for cows may contribute to udder health (less bacterial growth) and ammonia levels (lower ammonia levels on bedding).[84]

Agroforestry

Cocoa beans may be cultivated under shade, as done in agroforestry. Agroforestry can reduce the pressure on existing protected forests for resources, such as firewood, and conserve biodiversity.[85] Integrating shade trees with cocoa plants reduces risk of soil erosion and evaporation, and protects young cocoa plants from extreme heat.[77] Agroforests act as buffers to formally protected forests and biodiversity island refuges in an open, human-dominated landscape. Research of their shade-grown coffee counterparts has shown that greater canopy cover in plots is significantly associated with greater mammal species diversity.[86] The amount of diversity in tree species is fairly comparable between shade-grown cocoa plots and primary forests.[87]

Economic effects

Cocoa contributes significantly to Nigerian economic activity, comprising the largest part of the country's foreign exchange, and providing income for farmers.[88] Farmers can grow a variety of fruit-bearing shade trees to supplement their income to help cope with the volatile cocoa prices.[89] Although cocoa has been adapted to grow under a dense rainforest canopy, agroforestry does not significantly further enhance cocoa productivity.[90] However, while growing cocoa in full sun without incorporating shade plants can temporarily increase cocoa yields, it will eventually decrease the quality of the soil due to nutrient loss, desertification and erosion, leading to unsustainable yields and dependency on inorganic fertilizers. Agroforestry practices stabilize and improve soil quality, which can sustain cocoa production in the long term.[76]

Over time, cocoa agroforestry systems become more similar to forest, although they never fully recover the original forest community within the life cycle of a productive cocoa plantation (approximately 25 years).[91] Thus, although cocoa agroforests cannot replace natural forests, they are a valuable tool for conserving and protecting biodiversity while maintaining high levels of productivity in agricultural landscapes.[91]

In West Africa, where about 70% of global cocoa supply originates from smallholder farmers, recent public–private initiatives such as the Cocoa Forest Initiatives in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire (World Cocoa Foundation, 2017) and the Green Cocoa Landscape Programme in Cameroon (IDH, 2019) aim to support the sustainable intensification and climate resilience of cocoa production, the prevention of further deforestation and the restoration of degraded forests.[91] They often align with national REDD+ policies and plans.[91]

Consumption

People around the world enjoy cocoa in many different forms, consuming more than 3 million tons of cocoa beans yearly. Once the cocoa beans have been harvested, fermented, dried and transported they are processed in several components. Processor grindings serve as the main metric for market analysis. Processing is the last phase in which consumption of the cocoa bean can be equitably compared to supply. After this step all the different components are sold across industries to many manufacturers of different types of products.

Global market share for processing has remained stable, even as grindings increase to meet demand. One of the largest processing countries by volume is the Netherlands, handling around 13% of global grindings. Europe and Russia as a whole handle about 38% of the processing market. Average year after year demand growth has been just over 3% since 2008. While Europe and North America are relatively stable markets, increasing household income in developing countries is the main reason of the stable demand growth. As demand is awaited to keep growing, supply growth may slow down due to changing weather conditions in the largest cocoa production areas.[92]

Chocolate production

To make 1 kg (2.2 lb) of chocolate, about 300 to 600 beans are processed, depending on the desired cocoa content. In a factory, the beans are roasted. Next, they are cracked and then deshelled by a "winnower". The resulting pieces of beans are called nibs. They are sometimes sold in small packages at specialty stores and markets to be used in cooking, snacking, and chocolate dishes. Since nibs are directly from the cocoa tree, they contain high amounts of theobromine. Most nibs are ground, using various methods, into a thick, creamy paste, known as chocolate liquor or cocoa paste. This "liquor" is then further processed into chocolate by mixing in (more) cocoa butter and sugar (and sometimes vanilla and lecithin as an emulsifier), and then refined, conched and tempered. Alternatively, it can be separated into cocoa powder and cocoa butter using a hydraulic press or the Broma process. This process produces around 50% cocoa butter and 50% cocoa powder. Cocoa powder may have a fat content of about 12%,[93] but this varies significantly.[94] Cocoa butter is used in chocolate bar manufacture, other confectionery, soaps, and cosmetics.

Treating with an alkali produces Dutch process cocoa, which is less acidic, darker, and more mellow in flavor than untreated cocoa. Regular (non-alkalized) cocoa is acidic, so when cocoa is treated with an alkaline ingredient, generally potassium carbonate, the pH increases.[95] This process can be done at various stages during manufacturing, including during nib treatment, liquor treatment, or press cake treatment.

Another process that helps develop the flavor is roasting, which can be done on the whole bean before shelling or on the nib after shelling. The time and temperature of the roast affect the result: A "low roast" produces a more acid, aromatic flavor, while a high roast gives a more intense, bitter flavor lacking complex flavor notes.[96]

Phytochemicals and research

Cocoa contains various phytochemicals, such as flavanols (including epicatechin), procyanidins, and other flavonoids. A systematic review presented moderate evidence that the use of flavanol-rich chocolate and cocoa products causes a small (2 mmHg) blood pressure lowering effect in healthy adults—mostly in the short term.[97]

The highest levels of cocoa flavanols are found in raw cocoa and to a lesser extent, dark chocolate, since flavonoids degrade during cooking used to make chocolate.[98]

Methylxanthines

The beans contain theobromine, and between 0.1% and 0.7% caffeine, whereas dry coffee beans are about 1.2% caffeine.[99]

Theobromine found in the cocoa solids is fat soluble.[100]

See also

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of the World's Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people – In brief, FAO & UNEP, FAO & UNEP.

This article incorporates text from a free content work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 IGO (license statement/permission). Text taken from The State of the World's Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people – In brief, FAO & UNEP, FAO & UNEP.

References

- "Cacao". Free Dictionary. Retrieved 17 February 2015.

- "cocoa (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Bingham, Ann; Roberts, Jeremy (2010). South and Meso-American Mythology A to Z. Infobase Publishing. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-4381-2958-7.

- Kaufman, Terrence; Justeson, John (2006). "History of the Word for 'Cacao' and Related Terms in Ancient Meso-America". In Cameron L. McNeil (ed.). Chocolate in Mesoamerica: A Cultural History of Cacao. University Press of Florida. p. 121. ISBN 978-0-8130-3382-2.

- "cocoa (n.)". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- "Chocolate Facts". 11 June 2005. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- "Cacao Vs. Cocoa: Updating Your Chocolate Vocabulary". Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2007.

- Crozier, Stephen J.; Preston, Amy G.; Hurst, Jeffrey W.; Payne, Mark J.; Mann, Julie; Hainly, Larry; Miller, Debra L. (7 February 2011). "Cacao seeds are a "Super Fruit": A comparative analysis of various fruit powders and products". Chemistry Central Journal. 5 (5): 5. doi:10.1186/1752-153X-5-5. PMC 3038885. PMID 21299842.

Cacao (or cocoa) beans are technically not beans or legumes, but rather the seeds of the fruit of the Theobroma cacao tree.

- Roberto Ochoa (19 November 2017). "Jaén y la cultura Marañón". Lima: Domingo semanal (La República). Archived from the original on 7 May 2018. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "Sweet discovery pushes back the origins of chocolate: Researchers find cacao originated 1,500 years earlier than previously thought". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

- "The Earliest Chocolate Drink of the New World". Penn Museum. 13 November 2007. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013.

- Wood, G. A. R.; Lass, R. A. (2001). Cocoa. Tropical agriculture serie (4th ed.). John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-632-06398-7.

- Dillinger, Teresa L.; Barriga, Patricia; Escárcega, Sylvia; Jimenez, Martha; Lowe, Diana Salazar; Grivetti, Louis E. (1 August 2000). "Food of the Gods: Cure for Humanity? A Cultural History of the Medicinal and Ritual Use of Chocolate". The Journal of Nutrition. 130 (8): 2057S–2072S. doi:10.1093/jn/130.8.2057S. ISSN 0022-3166. PMID 10917925.

- Díaz del Castillo, Bernal (2005) [1632]. Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España. Felipe Castro Gutiérrez (Introduction). Mexico: Editores Mexicanos Unidos, S.A. ISBN 968-15-0863-7. OCLC 34997012

- "Chocolate History Time Line". Retrieved 8 November 2007.

- "The Philippine 2020 Cacao Challenge". Cacao Industry Development Association of Mindanao, Inc. (CIDAMi). Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- Spadaccini, Jim. "The Sweet Lure of Chocolate". The Exploratorium.

- "Theobroma cacao, the food of the gods". Barry Callebaut.

- Kowalchuk, Kristine. "Cuckoo for Cocoa". Westworld Alberta. Archived from the original on 28 February 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- "Criollo Chocolate: Efficient Food of the Gods". MetaEfficient. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- "Sensational Chocolates: Discover the Intense Robust flavor of 100% 'Grand Cru' Chocolate". Sensational Chocolates. Archived from the original on 28 March 2008. Retrieved 17 May 2008.

- Payany, Estérelle (2019). Ferrandi, Chocolate: Recipes and techniques from the Ferrandi school of culinary arts. Groupe Flammarion. p. 18. ISBN 9782081506794.

particularly tannic and has a more astringent and bitter taste than other varieties

- Fabricant, Florence (12 January 2011). "Rare Cacao Beans Discovered in Peru". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- Scheffler, Daniel (30 September 2015). "Fine chocolates now appreciated by connoisseurs as a luxury product". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- Giller, M.; Laiskonis, M. (2017). Bean-to-bar Chocolate: America's Craft Chocolate Revolution : the Origins, the Makers, and the Mind-blowing Flavors. Storey Publishing. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-61212-821-4. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- "What are the varieties of cocoa?". International Cocoa Organization. 21 July 1998. Archived from the original on 18 February 2006. Retrieved 27 June 2006.

- Fabricant, Florence (11 January 2011). "Rare Cacao Beans Discovered in Peru". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 February 2014.

- Zipperer, Paul (1902). The manufacture of chocolate and other cacao preparations (3rd ed.). Berlin: Verlag von M. Krayn. p. 14.

white cacao, ... Ecuador ... rare ... In Trinidad also

- Abenyega, Olivia & Gockowski, James (2003). Labor practices in the cocoa sector of Ghana with a special focus on the role of children. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-978-131-218-2.

- Hui, Yiu H. (2006). Handbook of food science, technology, and engineering. Vol. 4. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-9849-0.

- Dand, Robin (1999). The international cocoa trade (2nd ed.). Woodhead Publishing. ISBN 978-1-85573-434-0.

- Gockowski, J. & Oduwole, S. (2003). Labor practices in the cocoa sector of southwest Nigeria with a focus on the role of children. International Institute of Tropical Agriculture. pp. 11–15. ISBN 978-978-131-215-1.

- "Yeasts key for cacao bean fermentation and chocolate quality". Confectionery News. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- "FAQ : Products that can be made from cocoa". International Cocoa Organization. Archived from the original on 4 October 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2014.

- "Cocoa Life – A story on Farming – Cocoa Growing". Cocoa Life. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- Whitmore, Alex (10 April 2009). "Mexican Chocolate: Rustic, Stronger, Better". The Atlantic.

- Raghavan, Sudarsan; Chatterjee, Sumana (24 June 2001). "Slaves feed world's taste for chocolate: Captives common in cocoa farms of Africa". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Archived from the original on 17 September 2006. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- "Combating Child Labour in Cocoa Growing" (PDF). International Labour Organization. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 May 2005. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- Wolfe, David & Shazzie (2005). Naked Chocolate: The Astonishing Truth about the World's Greatest Food. North Atlantic Books. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-55643-731-1. Retrieved 15 December 2011.

- Hawksley, Humphrey (12 April 2001). "Mali's children in chocolate slavery". BBC News. Retrieved 2 January 2010.

- Hawksley, Humphrey (4 May 2001). "Ivory Coast accuses chocolate companies". BBC News. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- Payson Center for International Development and Technology Transfer (30 September 2010). "Fourth Annual Report: Oversight of Public and Private Initiatives to Eliminate the Worst Forms of Child Labor in the Cocoa Sector of Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana" (PDF). Tulane University. p. 26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- "Protocol for the growing and processing of cocoa beans and their derivative products in a manner that complies with ILO Convention 182 concerning the prohibition and immediate action for the elimination of the worst forms of child labor" (PDF). International Cocoa Initiative. 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2012.

- Escobedo, Tricia (19 September 2011). "The Human Cost of Chocolate". CNN. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Monsy, Karen Ann (24 February 2012). "The bitter truth". Khaleej Times. Archived from the original on 15 April 2012. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Payson Center for International Development and Technology Transfer (31 March 2011). "Oversight of Public and Private Initiatives to Eliminate the Worst Forms of Child Labor in the Cocoa Sector of Côte d'Ivoire and Ghana" (PDF). Tulane University. pp. 7–12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- "Harkin Engel Protocol". Slave Free Chocolate. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- "The human cost of chocolate". Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- "Human Rights and Child Labour". Make Chocolate Fair!. 13 August 2013. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- "Final Report 2013/14 Survey Research on Child Labor in West African Cocoa Growing Areas Tulane University Louisiana" (PDF). 30 July 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 December 2017.

- "Child Labor in the Production of Cocoa". Bureau of International Labor Affairs, United States Department of Labor, Washington, DC. 2018. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Kieran Guilbert (12 June 2017). "Falling cocoa prices threaten child labor spike in Ghana, Ivory Coast". Reuters. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- O'Keefe, Brian (1 March 2016). "Inside Big Chocolate's Child Labor Problem". Fortune.com. Fortune. Retrieved 7 January 2018.

For a decade and a half, the big chocolate makers have promised to end child labor in their industry—and have spent tens of millions of dollars in the effort. But as of the latest estimate, 2.1 million West African children still do the dangerous and physically taxing work of harvesting cocoa. What will it take to fix the problem?

- Oliver Balch (20 June 2018). "Child Labour: the true cost of chocolate production". Raconteur. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- Balch, Oliver (12 February 2021). "Mars, Nestlé and Hershey to face child slavery lawsuit in US". Retrieved 13 February 2021.

- "Cocoa bean production in 2020, Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists)". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Kisiedu, E. W.; Ntifo, S. E. A. (1975). "Problems of cocoa storage and shipment in Cameroon". In Kumar, R. (ed.). Proceedings of the Fourth Conference of West African Cocoa Entomologists, Legon, Cameroon, 1974. Zoology Department of University of Cameroon. pp. 104–105.

- Finkelman, S.; Navarro, S.; Rindner, M.; Dias, R.; Azrieli, A. (2003). "Effect of low pressures on the survival of cocoa pests at 18 °C". Journal of Stored Products Research. 39 (4): 423–431. doi:10.1016/S0022-474X(02)00037-1.

- "Historical Cocoa Intraday Futures Data (CCA)". PortaraCQG. Retrieved 12 May 2022.

- "International collaboration". Kakaoplattform. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- "Partnerships to make cocoa production more sustainable". Kakaoplattform. 30 April 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- "About ICCO". www.icco.org. Archived from the original on 4 October 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- Voora, V.; Bermudez, S.; Larrea, C. (2019). "Global Market Report: Cocoa". State of Sustainability Initiatives. Archived from the original on 22 January 2021.

- "Downloads | Fair Trade & Organic Cocoa | Related Documents". www.icco.org. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- "The COSA Measuring Sustainability Report – COSA". Committee on Sustainability Assessment. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. Retrieved 27 June 2022.

- "Gourmet Gardens: Congolese Fair Trade and Organic Cocoa". befair.be.

- "CONACADO: National confederation of cocoa producers". Archived from the original on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- "Beyond Chocolate". IDH - the sustainable trade initiative. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- Nieburg, Oliver (8 June 2016). "Ferrero to double Fairtrade cocoa purchases". Confectionery News.

- "The News on Chocolate is Bittersweet: No Progress on Child Labor, but Fair Trade Chocolate is on the Rise" (PDF). Global Exchange. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- "Fairtrade Cadbury Dairy Milk Goes Global as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand take Fairtrade Further Into Mainstream". Archived 30 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine Cadbury PLC 2010. Retrieved 1 July 2010.

- Nieburg, Oliver (19 November 2012). "Mondelez pumps $400m in sustainable cocoa supply chain". Confectionery News.

- Nieburg, Oliver (20 June 2016). "Cocoa sector remains 'far from' from sustainable". Confectionery News.

- "Certification for Farmers". UTZ.

- "Back to the future: Brazilian federal bill re-discovers sustainable cabruca cocoa bean production". confectionerynews.com. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- Schulte, I.; Landholm, D.M.; Bakhtary, H.; Cabezas, S.C.; Siantidis, S.; Manirajaj, S.M.; and Streck, C. (2020). Supporting smallholder farmers for a sustainable cocoa sector: Exploring the motivations and role of farmers in the effective implementation of supply chain sustainability in Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire (pp. 1–59, Rep.). Washington DC: Meridian Institute.

- Dohmen, M. M., Noponen, M., Enomoto, R., Mensah, C., & Muilerman, S. (2018). Climate-Smart Agriculture in Cocoa A Training Manual for Field Officers (pp. 1-111, Rep.). Washington DC: World Cocoa Foundation

- Stecker, Tiffany; ClimateWire (3 October 2011). "Climate Change Could Melt Chocolate Production". Scientific American.

- "Climate change: Will chocolate become a costly luxury?". The Week. 30 September 2011.

- Läderach, P.; Martinez-Valle, A.; Schroth, G.; Castro, N. (August 2013). "Predicting the future climatic suitability for cocoa farming of the world's leading producer countries, Ghana and Côte d'Ivoire". Climatic Change. 119 (3–4): 841–854. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0774-8. hdl:10.1007/s10584-013-0774-8. ISSN 0165-0009. S2CID 154596223.

- Heckel, Jodi (13 January 2022). "Climate adaptation increases vulnerability of cocoa farmers, study shows". phys.org.

- Nieburg, Oliver (21 December 2015). "'Devastating' impact of climate change on cocoa can't be ignored, says Rainforest Alliance". confectionerynews.com.

- Juniper, Tony (25 January 2020). "How climate change has altered cocoa farming in Ivory Coast". www.greenbiz.com.

- Yajima, Akira; Ohwada, Hisashi; Kobayashi, Suguru; Komatsu, Natsumi; Takehara, Kazuaki; Ito, Maria; Matsuda, Kazuhide; Sato, Kan; Itabashi, Hisao (2017). "Cacao bean husk: an applicable bedding material in dairy free-stall barns". Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences. 30 (7): 1048–1053. doi:10.5713/ajas.16.0877. ISSN 1011-2367. PMC 5495665. PMID 28002931.

- Bhagwat, Shonil A.; Willis, Katherine J.; Birks, H. John B.; Whittaker, Robert J. (2008). "Agroforestry: a refuge for tropical biodiversity?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 23 (5): 261–267. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2008.01.005. PMID 18359125.

- Caudill, S. Amanda; DeClerck, Fabrice J.A.; Husband, Thomas P. (2015). "Connecting sustainable agriculture and wildlife conservation: Does shade coffee provide habitat for mammals?". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 199: 85–93. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2014.08.023.

- Vebrova, Hana; Lojka, Bohdan; Husband, Thomas P.; Zans, Maria E. C.; Van Damme, Patrick; Rollo, Alexandr; Kalousova, Marie (2014). "Tree Diversity in Cacao Agroforests in San Alejandro, Peruvian Amazon". Agroforestry Systems. 88 (6): 1101–1115. doi:10.1007/s10457-013-9654-5. S2CID 18279989.

- Ambele, F. C.; Bisseleua Daghela, H. B.; Babalola, O. O.; Ekesi, S. (16 April 2018). "Soil-dwelling insect pests of tree crops in Sub-Saharan Africa, problems and management strategies-A review". Journal of Applied Entomology. Wiley. 142 (6): 539–552. doi:10.1111/jen.12511. ISSN 0931-2048. S2CID 90875055. (HBBD ORCID: 0000-0002-2696-8859). (SE ORCID: 0000-0001-9787-1360).

- Oke, D. O.; Odebiyi, K. A. (2007). "Traditional cocoa-based agroforestry and forest species conservation in Ondo State, Nigeria". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 122 (3): 305–311. doi:10.1016/j.agee.2007.01.022.

- Pédelahore, Philippe (2014). "Farmers Accumulation Strategies and Agroforestry Systems Intensification: The Example of Cocoa in the Central Region of Cameroon over the 1910–2010 Period". Agroforestry Systems. 88 (6): 1157–1166. doi:10.1007/s10457-014-9675-8. S2CID 18228052.

- The State of the World's Forests 2020. Forests, biodiversity and people. Rome: FAO & UNEP. 2020. doi:10.4060/CA8642EN. ISBN 978-92-5-132707-4. S2CID 241858489.

- "World Cocoa Foundation Market Update 2014" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 August 2014.

- Osakabe, Naomi; Baba, Seigo; Yasuda, Akiko; Iwamoto, Tamami; Kamiyama, Masumi; Tokunaga, Takahisa; Kondo, Kazuo (2004). "Dose-Response Study of Daily Cocoa Intake on the Oxidative Susceptibility of Low-Density Lipoprotein in Healthy Human Volunteers". Journal of Health Science. 50 (6): 679–684. doi:10.1248/jhs.50.679. ISSN 1344-9702.

12.1% fat

- "Cadbury Bournville Cocoa Powder Tin 250g". Sainsbury's (UK). Retrieved 16 November 2020.

Fat 21%, of which saturates 12%

- Nolan, Emily (2002). Baking For Dummies. For Dummies. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-7645-5420-9.

- Urbanski, John (27 May 2008). "Cocoa: From Bean to Bar". Food Product Design. Archived from the original on 5 June 2008.

- Ried, Karin; Fakler, Peter; Stocks, Nigel P (25 April 2017). "Effect of cocoa on blood pressure". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017 (5): CD008893. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008893.pub3. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6478304. PMID 28439881.

- "Cocoa nutrient for 'lethal ills'". BBC News. 11 March 2007. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- Kim, Jiyoung; Kim, Jaekyoon; Shim, J; Lee, CY; Lee, KW; Lee, HJ (2014). "Cocoa phytochemicals: Recent advances in molecular mechanisms on health". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 54 (11): 1458–72. doi:10.1080/10408398.2011.641041. PMID 24580540. S2CID 20314911.

- Baggott, MJ; Childs, E; Hart, AB; de Bruin, E; Palmer, AA; Wilkinson, JE; de Wit, H (July 2013). "Psychopharmacology of theobromine in healthy volunteers". Psychopharmacology. 228 (1): 109–18. doi:10.1007/s00213-013-3021-0. PMC 3672386. PMID 23420115.