Cadang-cadang

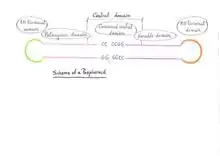

Cadang-cadang is a disease caused by Coconut cadang-cadang viroid (CCCVd), a lethal viroid of several palms including coconut (Cocos nucifera), African oil palm (Elaeis guineensis), anahaw (Saribus rotundifolius), and buri (Corypha utan). The name cadang-cadang comes from the word gadang-gadang that means dying in Bicol.[1] It was originally reported on San Miguel Island in the Philippines in 1927/1928. "By 1962, all but 100 of 250,000 palms on this island had died from the disease," indicating an epidemic.[2] Every year one million coconut palms are killed by CCCVd and over 30 million coconut palms have been killed since Cadang-cadang was discovered. CCCVd directly affects the production of copra, a raw material for coconut oil and animal feed. Total losses of about 30 million palms and annual yield losses of about 22,000 metric tons (22,000 long tons; 24,000 short tons) of copra have been attributed to Cadang-cadang disease in the Philippines.[3]

| Coconut cadang-cadang viroid | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Family: | Pospiviroidae |

| Genus: | Cocadviroid |

| Species: | Coconut cadang-cadang viroid |

Characteristics

Viroids are small, single-stranded RNA molecules, ranging from 246 to 375 nucleotides long. Unlike viruses, they do not code for protein coats but contain genes for autonomous replication. With abilities to cause serious disease, they are more commonly found in a latent stage, and their mode of infection is mainly mechanical, though documented cases exist of vertical transmission through pollen and seed.[4] The sequence and structure prediction of CCCVd has been documented. There are four low-molecular-weight RNA species (ccRNAs) found associated with cadang-cadang disease.[5] Of the four, two are related with the early stage of the disease: ccRNA 1 fast and ccRNA 2 fast. After several years, two other species appear and predominate: ccRNA 1 slow and ccRNA 2 slow. Moreover, they share sequence homology with other viroids.[2]

Conditions for a viroid to infect its host include wounds on the host or infected pollen grain deposited into an ovule.[6] Not all of the mentioned conditions pertain to cadang-cadang.

Tinangaja disease is caused by coconut trinangaja viroid (CTiVd), which has 64% sequence homology with CCCVd. This disease has been found in Guam. Coconuts from Asia and the South Pacific have been found to have viroids with similar (homologous) nucleic acid sequences of CCCVd. The pathogenicity of CTiVd is uncertain.[7] Coconut cadang-cadang viroid, also known as CCCVd, is responsible for a lethal disease of coconut plant first reported in the early 1930 in the Philippines. CCCVd is the smallest known pathogen and it is biologically distinct from other viroids; it consists of circular or lineal single-stranded RNA with a basic size of 246 or 247, it is thought it can be transmitted by seed or pollen (with low transmission rates) and occur in almost all plant parts. Once infected, coconut palm shows yellow leaf spots and nut production ceases; from appearance of first symptoms to tree death, time ranges from around 8 to 16 years, but the pest is generally greater in older plants. It is estimated that over 30 million coconut palms have been killed by cadang-cadang since it was first recognised and the loss of production is valued at about $80 – $100 for each planting site occupied by an infected tree.

Molecular structure

CCCVd are small, circular, and single-stranded. They cannot replicate themselves, and therefore are completely dependent on a host.

CCCVd have a sequence of 246 nucleotides, 44 of which are common with most viroids.[2] CCCVd can add a cytosine residue in the 197 position and increase the size to 247 nucleotides. It is known that forms of CCCVd with 247 nucleotides cause severe symptoms. Their minimum size is 246, but they can produce forms from 287 to 301 nucleotides.[1]

In CCCVd, changes in molecular forms are related to the steps of the disease. There are four different RNAs found in CCCVd, two of them fast and the other two slow (the difference between fast and slow RNA is their mobilities in electrophoresis gel). In the early stages of the disease, RNA fast 1 and RNA fast 2 appear, while in the late stages RNA slow 1 and RNA slow 2 are detected.

Geographical distribution

The CCCVd is widely spread in Philippines and it is mostly found in Bicol Region, Masbate, Catanduanes, Samar and other smaller islands in the zone. It is known that the present northernmost boundary is at the latitude of Manila and the southernmost at the latitude of Homonhon Island. This fact is important due to the proximity of the disease to the major coconut and oil palm growing area of Mindanao.[8] An isolated focus of infection has been found on the Solomon Islands, in Oceania.

The available data at the present suggests that the epidemiology of cadang-cadang viroid may not be spreading into any specific route.

Variants

In Guam, a similar viroid known as coconut tinangaja viroid (CTiVd) has been found that causes a similar disease named tinangaja disease. This viroid has 64% sequence homology with the cadang-cadang viroid.[9] There are other related viroids with the CCCVd, which are found in Asia and the South Pacific. They have a high degree of homology but the pathogenicity is uncertain.[10]

Transmission

The mode of natural inoculation of the viroid is unknown. There has been evidence that the transmission through pollen and seed can occur but they have a very low transmission rates: progenies of healthy palms pollinated with diseased pollen, exhibited disease symptoms 6 years after germination.[11]

CCCVd can spread through mechanical inoculation primarily through contaminated farm tools such as harvesting scythes or machetes, due to the improper sanitary conditions.[12] The efficiency of the mechanical inoculation has been influenced by factors such as the age of the test plant and the mode of inoculation.

Experimental transmission of the CCCVd using insects as vector has been unsuccessful although there are few evidences that the transmission of the viroid might be related to the wounds of coelopteran insects, but this has not been properly investigated.[12]

The natural hosts of cadang-cadang identified are Cocos nucifera, Corypha utan, Elaeis guineensis and Roystonea regia. The experimental hosts are Adonidia merrillii, Areca catechu, Caryota cumingii, Dypsis lutescens, Saribus rotundifolius, Phoenix dactylifera, Ptychosperma macarthurii and Roystonea regia.[13]

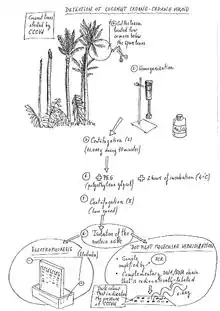

Detection

The diagnosis by symptoms is not reliable enough so it's better to do a molecular diagnosis based in test samples. Some of these methods (like Dot-blot hybridisation) allow the scientists to detect the viroid even six months before noticing the first symptoms.

The first step is the purification to obtain the nucleic acids of the plant cells. The leaves of the plant located four or more below the spare leaf are cut. Afterwards, they are blended (homogenize) with sodium sulfite. Then the extract is filtered and clarified by centrifugation (10.000 g during 10 minutes). The next step is to add polyethylene glycol (PEG). Finally, after nearly two hours of incubation at 4 °C, and after another centrifugation (at low speed) the nucleic acids can be extracted by chloroform procedures, for example.

When approximately 1 g of coconut tissue has been purified, the electrophoresis method can be started, which will help to identify the viroid by its relative mobility.[7] The CCCVd is analysed in one or two dimensional polyacrylamide gels with a silver stain.

The viroid can also be detected by a more sensitive method called dot blot molecular hybridization.[14] In this method CCCVd is amplified by the PCR (polymerase chain reaction) and the clones of CCCVd are used as templates to synthesize a complementary DNA or RNA chain. These sequences are radioactively labelled so when they are put over the samples with the intention to analyse (on a supporting membrane) and exposed to x-ray film, then if CCCVd is present it will appear as a dark colour. This dark tonality only appears when nucleic acid hybridisation occurs.

Pharmacology and treatment

Coconut cadang-cadang disease has no treatment yet. However, chemotherapy with antibiotics has been tried with tetracycline solutions; antibiotics failed trying to alter progress of the disease since they had no significant effect on any of the studied parameters. When the treated plants were at the early stage, tetracycline injections failed to prevent the progression of the palms to more advanced stages, nor did they affect significantly the mean number of spathes or nuts. Penicillin treatment had no apparent improvement either.

Control strategies are elimination of reservoir species, vector control, mild strain protection and breeding for host resistance.[15] Eradication of diseased plants is usually performed to minimize spread but is of dubious efficacy due to the difficulties of early diagnosis as the virus etiology remains unknown and the one discovered are the three main stages in the disease development.

Easily confused pests

Coconut Cadang Cadang Viroid (CCCVd) can be confused with another viroid called Coconut Tinangaja Viroid (CTiVd). That is because both viroids have 64% of their sequence of nucleotides in common. They both affect coconut palm, and infected plants have similar symptoms: spots on the leaves reduced top, yellow palms and even death.[16]

There are few differences between both viroids in the effects caused on fruit: CTiVd causes small nuts, while CCCVd causes round and reduced nuts. Moreover, CTiVd has 254 nucleotides of length, while CCCVd has 246.

Symptoms

Symptoms of cadang-cadang develop slowly over 8 to 15 years making it difficult to diagnose at an early time.[6] There are three main “stages” of defined series of characteristics: early, medium, and late stages.[17] The first symptoms in the early stage develop within two to four years of infection.[17] These symptoms include scarification of the coconuts which also become rounded. The leaves (fronds) display bright yellow spots. About two years later, during the medium stage,[18] the inflorescences become stunted and eventually killed, so no more coconuts are produced. Yellow spots are larger and in greater abundance to give the appearance of chlorosis. During the final stage, roughly 6 years after the first symptoms are recorded, the yellow/bronze fronds start to decrease in size and number. Finally, all the leaves coalesce, leaving just the trunk of the palm “standing like a telephone pole”.[6]

Palms under 10 years of age are rarely affected by cadang-cadang; the incidence of disease increases until about 40 years of age and then plateaus.[19] "No recovery has ever been observed, and the disease is always fatal".[4] African oil palm has similar symptoms as coconut but also have orange spotting on palms.[20]

Environment

Geographical location

Philippines: Southern Luzon, Samar, Masbate, and other small islands. Tinangaja was found in Guam on Mariana Islands.[19] Evidence shows that CCCVd is negatively correlated with altitude.[3]

Dispersal

The CCCVd viroid can be transmitted by pollen, seed, and mechanical transmission; it infects almost all parts of the host after flowering.

Insect vectors

No insect vector is known at this time, and rate of dispersal is not related to proximity of clusters.

Control

No definite control measures exist at the present.

- Genetic resistance and Vector control are not options because resistant/tolerant varieties have yet to be discovered, and there is no known vector of CCCVd.

- Eradication is ineffective because of the long latent period between infection and appearance of symptoms, which is approximately 1 to 2 years.

- Cross-protection (see also Influenza vaccine: Cross-protection) is a possibility for the future. Cross infection means inoculating the coconut with a mild strain of the viroid to give the coconut tree some degree of protection from infection by the killer form. This is similar to Edward Jenner's pioneering smallpox vaccine. He used cowpox to confer induced immunity on humans.[21] But in the case of Cadang-cadang, this is still under research.

References

- Hanold, D.; Randles, J. W. (1991). "Coconut Cadang-Cadang Disease and Its Viroid Agent". Plant Disease. American Phytopathological Society. 75 (4): 330–335. doi:10.1094/PD-75-0330. (Waite Agricultural Research Institute, University of Adelaide Glen Osmond, South Australia)

- Haseloff J.; Mohamed N.A.; Symons R.H. (1982). "Viroid RNAs of cadang-cadang disease of coconuts". Nature. 299 (5881): 316–321. Bibcode:1982Natur.299..316H. doi:10.1038/299316a0. S2CID 4232530.

- Zelazny B (1980). "Ecology of Cadang-Cadang Disease of Coconut Palm in the Philippines". Phytopathology. 70 (8): 700–703. doi:10.1094/phyto-70-700.

- Maramorosch, K. (1991). Viroids and Satellites: Molecular Parasites at the Frontier of Life. Boston: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-6783-2.

- Imperial J.S.; Rodrieguez J.B.; Randles J.W. (1981). "Variation in the Viroid-Like RNA Associated With Cadang-Cadang Disease: Evidence for an Increase in Molecular Weight With Disease Progress". Journal of General Virology. 56: 77–85. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-56-1-77.

- Agrios 2005, pages 822-823.

- Hanold, D.; Randles, J. W. (1991). "Detection of coconut cadang-cadang viroid-like sequences in oil and coconut palm and other monocotyledons in the south-west Pacific". Annals of Applied Biology. Association of Applied Biologists/Wiley-Blackwell. 118 (1): 139–151. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7348.1991.tb06092.x. ISSN 0003-4746.

- Randles, J.W., Hanold, D., Pacumba, E.P., and Rodriguez, M. J. B. Cadang-cadang disease of coconut palm. In: Plant Diseases of International Importance. A. N. Mukhopadhyay, J. Kumar, H.S. Chabue, and U. S. Singh, eds. Pretice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. In press. 1991

- Boccardo, G., Beaver, R. G., Randles, J.W., and Imperial, J.S. Tinangaja and bristle top, coconut diseases of uncertain etiology in Guam and their relationship to cadang-cadang disease of coconut in Philippines.1981

- EPPO Quarantine Pest and CABI. Coconut cadang-cadang viroid. Data sheets on Quarantine Pests 1978

- Pacumbaba, E.B.; Zelazny, B.; Orense, J.C. (Philippine Coconut Authority, Banao, Guinobatan, Albay (Philippines). Albay Research Center. Pollen and seed transmission of the coconut cadang-cadang viroid. May 1992.

- Zelazny, B., Randles, J. W., Boccardo, G., and Imperial J.S 1982. The viroid nature of the cadang-cadang disease of coconut palm. Scientia Flipinas, 1979

- Batugal, P., Ramanatha Rao, V., Oliver, J. (eds.) Coconut Genetic Resources. 2005

- Symons R.H. (1985). "Dot blot procedure with 32P DNA probes for the sensitive detection of avocado sunblotch and other viroids in plants". Journal of Virological Methods. 10 (2): 87–98. doi:10.1016/0166-0934(85)90094-1. PMID 3980666.

- Boccardo G., Randles J. W., Retuerma M. L. and Rillo Erlinda P., Transmission of the RNA Species Associated with Cadang-Cadang of coconut plant and the Insensivity of the Disease to Antibiotics, 1977.

- Bigornia, Q12 Philippine Journal of Coconout Studies, 1977.

- Philippine Coconut Authority. Coconut Cadang-Cadang Disease Primer. Philippine Coconut Authority. PCA. Web. 23 Oct. 2011. <http://www.pca.da.gov.ph Archived 2011-10-09 at the Wayback Machine>.

- European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization, CABI. (2008). Coconut Cadang-cadang viroid [Data file]. Retrieved from http://www.eppo.org/QUARANTINE/virus/Coconut_cadang_cadang_viroid/CCCVD0_ds.pdf Archived 2010-07-13 at the Wayback Machine

- Randles, J.W.; Imperial, J.S. (July 1984). Coconut cadang-cadang viroid. Retrieved from http://www.dpvweb.net/dpv/showadpv.php?dpvno=287 Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Coconut cadang-cadang viroid. (2008). [Caption under Cadang-cadang photo May 4, 2010]. Coconut Cadang-cadang viroid: cocadviroid CCCVd. Retrieved from http://www.invasive.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=0656010 on 20 Now. 2011.

- Stefan Riedel, MD (January 2005). "Edward Jenner and the history of smallpox and vaccination". Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 18 (1): 21–25. doi:10.1080/08998280.2005.11928028. PMC 1200696. PMID 16200144.

External links

- Agrios, G. N. (2005). Plant Pathology pp. 822–823. (5th ed.). Burlington, MA: Elsevier Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-12-044565-3

- Coconut cadang-cadang viroid. (2008). [Caption under Cadang-cadang photo May 4, 2010]. Coconut Cadang-cadang viroid: cocadviroid CCCVd. Retrieved from http://www.invasive.org/browse/detail.cfm?imgnum=0656010 on 20 Now. 2011.

- European and Mediterranean Plant Protection Organization, CABI. (2008). Coconut Cadang-cadang viroid [Data file]. Retrieved from https://web.archive.org/web/20100713213014/http://www.eppo.org/QUARANTINE/virus/Coconut_cadang_cadang_viroid/CCCVD0_ds.pdf on 3 Nov. 2011.

- Hanold, D.; Randles, J.W.. (1991a) Coconut cadang-cadang disease and its viroid agent. Plant Disease 75, 330-335.

- Hanold, D.; Randles, J.W. (1991b) Detection of coconut cadang-cadang viroid-like sequences in oil and coconut palm and other monocotyledons in the South-west Pacific. Annals of Applied Biology 118, 139-151.

- Haseloff J.; Mohamed N.A.; Symons R.H. (1982). "Viroid RNAs of cadang-cadang disease of coconuts". Nature. 299 (5881): 316–321. Bibcode:1982Natur.299..316H. doi:10.1038/299316a0. S2CID 4232530.

- Imperial J.S.; Bautista R.M.; Randles J.W. (1985). "Transmission of the Coconut cadang-cadang Viroid to Six Species of Palm by Inoculation with Nucleic Acid Extracts". Plant Pathology. 34 (3): 391–401. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3059.1985.tb01378.x.

- Imperial J.S.; Rodrieguez J.B.; Randles J.W. (1981). "Variation in the Viroid-Like RNA Associated With Cadang-Cadang Disease: Evidence for an Increase in Molecular Weight With Disease Progress". Journal of General Virology. 56: 77–85. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-56-1-77.

- Maramorosch, K. (1991). Viroids and Satellites: Molecular Parasites at the Frontier of Life (127-139). Boston: CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-6783-2

- Philippine Coconut Authority. Coconut Cadang-Cadang Disease Primer. Philippine Coconut Authority. PCA. Web. 23 Oct. 2011. <http://www.pca.da.gov.ph Archived 2011-10-09 at the Wayback Machine>.

- Randles, J.W.; Imperial, J.S. (1984) Coconut cadang-cadang viroid. CMI/AAB Descriptions of Plant Viruses No. 287. Association of Applied Biologists, Wellesbourne, UK.

- Randles, J.W.; Imperial, J.S. (July 1984). Coconut cadang-cadang viroid. Retrieved from http://www.dpvweb.net/dpv/showadpv.php?dpvno=287 Archived 2015-09-23 at the Wayback Machine

- Randles, J. W. (1987). Coconut Cadang-Cadang. In Diener, T. O. (Eds.) The Viroids (265-277). New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-42523-3

- Zelazny B (1980). "Ecology of Cadang-Cadang Disease of Coconut Palm in the Philippines". Phytopathology. 70 (8): 700–703. doi:10.1094/phyto-70-700.

- Mohammadi MR, Vadamalai G, Joseph H (2010). "An optimized method for extraction and detection of Coconut cadang-cadang viroid(CCCVd) from oil palm". Commun. Agric. Appl. Biol. Sci. 75 (4): 777–81. PMID 21534490.