Collapse of the Atlantic northwest cod fishery

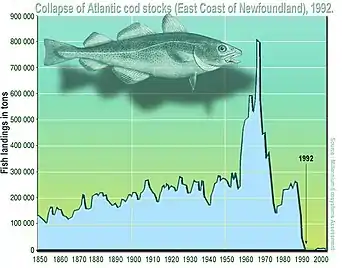

In 1992, Northern Cod populations fell to 1% of historical levels, due in large part to decades of overfishing.[3] The Canadian Federal Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, John Crosbie, declared a moratorium on the Northern Cod fishery, which for the preceding 500 years had primarily shaped the lives and communities of Canada's eastern coast.[4] A significant factor contributing to the depletion of the cod stocks off Newfoundland's shores was the introduction of equipment and technology that increased landed fish volume.[5] From the 1950s onwards, new technology allowed fishers to trawl a larger area, fish more in-depth, and for a longer time. By the 1960s, powerful trawlers equipped with radar, electronic navigation systems, and sonar allowed crews to pursue fish with unparalleled success, and Canadian catches peaked in the late-1970s and early-1980s.[4] Cod stocks were depleted at a faster rate than could be replenished.[4]

The trawlers also caught enormous amounts of non-commercial fish, which were economically unimportant but very important ecologically. This incidental catch undermined the stability of the ecosystem by depleting stocks of important predator and prey species.

Technological factors

A significant factor contributing to the depletion of the cod stocks off the shores of Newfoundland included the introduction and proliferation of equipment and technology that increased the volume of landed fish. For centuries, local fishers used technology that limited the volume of their catch, the area they fished, and let them target specific species and ages of fish.[5] From the 1950s onwards, as was common in all industries, new technology was introduced that allowed fishers to trawl a larger area, fish deeper and for a longer time. By the 1960s, powerful trawlers equipped with radar, electronic navigation systems, and sonar allowed crews to pursue fish with unparalleled success, and Canadian catches peaked in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[4]

The new technologies adversely affected the northern cod population by both increasing the area and depth that was fished. The cod were being depleted until the surviving fish could not replenish the stock lost each year.[4] The trawlers caught enormous amounts of non-commercial fish, which were very important ecologically. Economically unimportant incidental catch undermines ecosystem stability, depleting stocks of important predator and prey species. Significant amounts of capelin – an important prey species for the cod – were caught as bycatch, further undermining the survival of the remaining cod stock.

Ecology

Poor knowledge and understanding of the ocean ecosystem related with Newfoundland's Grand Banks and cod fisheries, as well as technical and environmental challenges associated with observational metrics, led to a misunderstanding of data on the "cod stocks" (meaning residual and recoverable fish). Rather than metrics of megatonnage of harvest, or average size of fish,[7] metrics of the residuum with high variation in the countable population due to sampling error, and dynamic environmental factors such as ocean temperature combined to make it difficult to discern the effects of exploitation to an inexpert regulator.[8] This led to uncertainty of predictions about the "cod stock," making it difficult for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans in Canada to choose the appropriate course of action when the federal government's priorities were elsewhere.[9]

Socioeconomic factors

In addition to ecological considerations, decisions regarding the future of the fisheries were also influenced by social and economic factors. Throughout Atlantic Canada, but especially in Newfoundland, the cod fishery was a source of social and cultural identity.[10] For many families, it also represented their livelihood: most families were connected either directly or indirectly with the fishery as fishermen, fish plant workers, fish sellers, fish transporters, or as employees in related businesses.[10] Additionally, many companies, both foreign and domestic, and individuals had invested heavily in the fishery's boats, equipment, and infrastructure.

Mismanagement

In 1949 Newfoundland joined Canada as a province, and thus Newfoundland's fishery fell under the management of the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). The department mismanaged the resource and allowed overfishing.[11][12]

In 1969 the number of fishing trawlers increased, and coastal fishermen complained to the government.[13] This resulted in the government redefining the offshore fishery boundaries several times and eventually extended its limits from 3 to 200 nautical miles (6 to 370 km; 3 to 230 mi) offshore,[12] as part of its claim for an exclusive economic zone under the UNCLOS.

In 1968 the cod catch peaked at 810,000 tons, approximately three times more than the maximum yearly catch achieved before the super-trawlers. Around eight million tons of cod were caught between 1647 and 1750 (103 years), encompassing 25 to 40 cod generations. The factory trawlers took the same amount in 15 years.[14]

In 1976, the Canadian government declared the right to manage the fisheries in an exclusive economic zone that extended to 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) offshore. The government wanted to reverse declining fish stocks by removing foreign fishing within the new inshore fishery boundaries.[12] Fish mortality decreased immediately.[13] This was not due to a rise in cod stocks but because foreign trawlers could no longer fish the waters. Therefore, when Fisheries and Oceans set quotas, they overestimated the total supply and increased the total allowable catch.[14] With the absence of foreign fishing, many Canadian and U.S fishing trawlers took their place, and the number of cod kept diminishing past a point of recovery.[12]

Many local fishers noticed the drastic decrease of cod and tried to inform local government officials.

In a 1978 white paper, the Newfoundland government stated:[15]

It must be recognised that both the Federal and Provincial Governments, plant workers, and the private sector, which includes fishermen, all have a role to play at influencing and directing the course of development within the fisheries sector. It is essential, therefore, that various interest group conflicts be minimized and that the appropriate measures be taken to ensure that benefits accruing from the exploitation of fish stocks are consistent with rational resource management objectives and desirable socio-economic considerations.

In 1986, scientists reviewed calculations and data, after which they determined, to conserve cod fishing, the total allowable catch rate had to be cut in half. However, even with these new statistics brought to light, no changes were made in the allotted yearly catch of cod.[12] With only a limited knowledge of cod biology, scientists predicted that the population of the species would rebound from its low point in 1975.

In the early-1990s, the industry collapsed entirely.

In 1992, John Crosbie, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, set the quota for cod at 187,969 tonnes, even though only 129,033 tonnes had been caught the previous year.

In 1992 the government announced a moratorium on cod fishing.[12] The moratorium was at first meant to last two years, hoping that the northern cod population would recover and the fishery. However, catches were still low,[16] and thus the cod fishery remained closed.

By 1993 six cod populations had collapsed, forcing a belated moratorium on fishing.[14] Spawning biomass had decreased by at least 75% in all stocks, by 90% in three of the six stocks, and by 99% in the case of "northern" cod, previously the largest cod fishery in the world.[14] The previous increases in catches were wrongly thought to be due to "the stock growing" but were caused by new technologies such as trawlers.[13]

Intense fishing pressure also contributed to fisheries-induced evolution in Northern cod. Prior to the collapse of the population, maturation reaction norms of Northern cod shifted towards younger ages and smaller sizes in the decade leading up to the collapse.[17] Small size at maturity has continued into the mid 2000s, despite stricter fishing regulations, which supports the theory that there have been genetic changes in growth in Northern cod populations in response to size-selective fishing.[18] In addition, this trend has been attributed to a hypothesis suggesting that selection differentials from the environment are not as strong as the artificial selection differentials imposed by heavy fishing.[19] Other factors for the slow recovery of the original life-history characteristics of cod include lower genetic heritable variation due to overexploitation. It has been estimated that such a full recovery of life-history characteristics in a population of cod may take up to 84 years.[20]

Impact on Newfoundland

Approximately 37,000 fishermen and fish plant workers lost their jobs due to the collapse of the cod fisheries; many people had to find new jobs or further their education to find employment.

The collapse of the northern cod fishery marked a profound change in the ecological, economic and socio-cultural structure of Atlantic Canada. The moratorium in 1992 was the largest industrial closure in Canadian history,[21] and it was expressed most acutely in Newfoundland, whose continental shelf lay under the region most heavily fished. Over 35,000 fishermen and plant workers from over 400 coastal communities became unemployed.[10] In response to dire warnings of social and economic consequences, the federal government initially provided income assistance through the Northern Cod Adjustment and Recovery Program, and later through the Atlantic Groundfish Strategy, which included money specifically for the retraining of those workers displaced by the closing of the fishery.[3] Newfoundland has since experienced a dramatic environmental, industrial, economic, and social restructuring, including considerable outward migration,[22] and increased economic diversification, an increased emphasis on education. As the predatory groundfish population declined, a thriving invertebrates fishing industry emerged, snow crab and northern shrimp proliferated, providing the basis for a new initiative that is roughly equivalent in economic value to the cod fishery it replaced.[3]

Post-collapse management

In 1997 the Minister for DFO partly lifted the ban on Canadian cod fishing, ten days before a federal election. However, independent Canadian scientists and the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea doubted there had been sufficient recovery.[23] In general, depleted populations of cod and other gadids do not appear to recover easily when fishing pressure is reduced or stopped.[24]

In 1998 the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) assessed Atlantic Cod. COSEWIC's designations, in theory, are informed by reports that it commissions and by expert discussion in the panel, and it claims to be scientific and apolitical. Recognizing faults in processes is not recreational but an essential step in their improvement. In this case much was mishandled. One observer opined "this process stinks";[25] the same observer later joined, and then became Chair of, COSEWIC. COSEWIC listed Atlantic cod as "vulnerable" (this category later renamed "special concern") on a single-unit basis, i.e. assuming a single homogeneous population. The basis (single-unit) of designation and the level (vulnerable) assigned was in contrast to the range of designations including "endangered"[25][26] for some of the ten management (sub) units addressed in the report[27] that COSEWIC had commissioned from Dr. K.N.I. Bell. That contradiction between the report and the listing reflected political pressure from the DFO; such bureaucratic pressure had been evident through three years of drafts.

The 1998 designation followed on from a deferral in 1997 and bureaucratic tactics including what one COSEWIC insider characterized as "a plan to make it late."[25][28] Press interest before the 1998 meeting[26] had, however, likely deterred a further deferral. COSEWIC's 'single unit' basis of listing was at the behest of DFO, although DFO had previously in criticism demanded (properly, given the new evidence) that the report address multiple stocks. Bell had agreed with that criticism and revised accordingly, but DFO then changed its mind without explanation.

By the time of COSEWIC's 1998 cod discussion, the Chair had been ousted for having said, "I have seen a lot of status reports ... it is as good as I have ever seen in regards to content."[25] COSEWIC had already attempted to alter[29] the 1998 report unilaterally. The report remains one of an undeclared number that is illegally suppressed (COSEWIC refuses to officially release it unless it can change it "so that it ... reflects COSEWIC's designation"),[28] in this case despite kudos from eminent reviewers of COSEWIC's own choice.[30] COSEWIC in defense asserted a right to alter the report or that Bell had been asked to provide a report that supported COSEWIC's designation;[28] either defense would involve explicit violations of ethics, of COSEWIC's procedures at the time, and norms of science. The key tactics used to avert any at-risk listing centered on the issue of stock discreteness, and DFO's single-stock stance within COSEWIC contradicted the multiple-stock hypothesis supported by the most recent science (including DFO's, hence DFO's earlier and proper demand that the report address these). Bell has argued that this contradiction between fact and tactic effectively painted management into a corner. It could not acknowledge or explain the contrast between areas where conservation measures were needed and areas where opposite observations were gaining press attention.[31]

In 1998, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) listed the Atlantic cod as "vulnerable," a category subsequently rebranded as "special concern," though not as an endangered species. This decision process is formally supposed to be informed by Reports that are commissioned from authors. Dr. Kim N.I. Bell authored the 1998 Status Report for COSEWIC.[32][33] This was the first such report on a commercial fish species in Canada. The potential designation change (from Not At Risk to Endangered) was highly contentious because many considered that the collapse of Atlantic Cod had ultimately resulted from mismanagement by DFO. The Report (section: Author's Recommendation of Status) therefore discussed at great length the process of developing a recommendation for the designation. The Report contained discussion addressing points that DFO had offered because although COSEWIC had a mechanism for the 'jurisdiction' (i.e., the department responsible for the 'species' (here, for the population), to provide objections to an author), it had no mechanism for those objections to be objectively arbitrated as a matter of science. Rebuttal by authors was untraditional and unexpected. That is undoubtedly why, before the meeting which was to decide the designation, COSEWIC had massively unannouncedly edited the Report, thereby introducing many errors and changing meanings, including removing the word "few" from "there are few indications of improvement," and expunging a substantial section which engaged various objections raised by DFO. When the author discovered the unauthorized "edits," COSEWIC was obliged to circulate a letter explaining that it had sent out a version that lacked the author's approval and had to provide the author's version to members.[34][35]

The Report contained, under a subsection "Designation by geographic management units (as preferred by DFO in 1996)", recommendations (or options) for 10 geographic management units, being Not At Risk or Vulnerable (for 1 management area), Threatened or Endangered (for 5 management areas), and to Endangered (for 4 management areas). In its designation, COSEWIC:

- Disregarded population structure and provided a recommendation based on the presumption of a single homogeneous population (which even DFO's own internal documents concluded was unlikely, compared to heterogeneity).

- Disregarded the arithmetic that clearly put declines in high "at risk" categories, and applied a decision of vulnerable, a lower-risk category, to the entire species within Canadian waters.

COSEWIC did not account for its designation variation from the Report's recommendation and did not admit that variation. COSEWIC also refused to release the Report, although its rules required it to. Bell, the Report's author, subsequently stated that political pressure by the DFO within COSEWIC was what accounted for the difference.[25]

In 1998 in a book, Bell argued[36] that the collapse of the fishery and the failure of the Listing process was ultimately facilitated by secrecy (as long ago in the defense science context observed by the venerable C. P. Snow[37] and recently cast as "government information control" in the fishery context[38]) and the lack of a code of ethics appropriate to (at least) scientists whose findings are relevant to conservation and public resource management. He wrote that a proper code of ethics would acknowledge the obligations of all to conservation, the right of the public to know and understand scientific findings, the obligation of scientists to communicate vital issues with the public, and would not acknowledge the right of bureaucrats to impede[39] that dialogue, and that to be effective, such ethical issues need to be included in science curricula.

Mark Kurlansky, in his 1999 book about cod, wrote that the collapse of the cod fishery off Newfoundland, and the 1992 decision by Canada to impose an indefinite moratorium on the Grand Banks, is a dramatic example of the consequences of overfishing.[40]

Later developments

In 2000, WWF placed cod on the endangered species list. The WWF issued a report stating that the global cod catch had dropped by 70% over the last 30 years and that if this trend continued, the world's cod stocks would disappear in 15 years.[41] Åsmund Bjordal, director of the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research, disputed the WWF's claim, noting the healthy Barents Sea cod population.[42] Cod (known in Norway as skrei or torsk) is among Norway's most important fishery exports, and the Barents Sea is Norway's most important cod fishery. In 2015, the Norwegian Seafood Council invited Crown Prince Haakon to take part in opening the year's cod fishing season on the island of Senja.[43]

By 2002, after a 10-year moratorium on fishing, the cod had still not returned.[44] The local ecosystem seemed to have changed, with forage fish, such as capelin, which used to provide food for the cod, increase in numbers, and eat the juvenile cod. The waters appeared to be dominated by crab and shrimp rather than fish.[44] Local inshore fishermen blamed hundreds of factory trawlers, mainly from Eastern Europe, which started arriving soon after WWII, catching all the breeding cod.[44]

In 2003, COSEWIC in an update designated the Newfoundland and Labrador population of Atlantic cod as endangered, and Fisheries Minister Robert Thibault announced an indefinite closure of the cod fishery in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and off the northeast coast of Newfoundland, thus closing the last remaining cod fishery in Atlantic Canada. In the Canadian system, however, under the 2002 Species at Risk Act (SARA)[45] the ultimate determination of conservation status (e.g., endangered) is a political, cabinet-level decision;[45] Cabinet decided not to accept COSEWIC's 2003 recommendations. Bell has explained[31] how both COSEWIC and public perceptions were manipulated, and the governing law broken, to favor that decision.

In 2004, the WWF in a report agreed that the Barents Sea cod fishery appeared to be healthy, but that the situation may not last due to illegal fishing, industrial development, and high quotas.[46]

In The End of the Line: How Overfishing Is Changing the World and What We Eat, author Charles Clover claims that cod is only one example of how the modern unsustainable fishing industry is destroying ocean ecosystems.[47]

In 2005, the WWF—Canada accused foreign and Canadian fishing vessels of deliberate large-scale violations of the restrictions on the Grand Banks, in the form of bycatch. WWF also claimed poor enforcement by NAFO, an intergovernmental organization with a mandate to provide scientific fishery advice and management in the northwestern Atlantic.[48][49]

In 2006, the Norwegian Institute of Marine Research considered coastal cod (but not the North East Arctic cod) endangered, but has since reversed this assessment.[50]

In November 2006, Fisheries and Oceans Canada released an article suggesting that the unexpectedly slow recovery of the cod stock was due to inadequate food supplies, cooling of the North Atlantic, and a poor genetic stock due to the overfishing of larger cod.[51]

In 2010 a study by the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization found that stocks in the Grand Banks near Newfoundland and Labrador had recovered by 69% since 2007, though that number only equated to 10% of the original stock.[52]

In 2010, Greenpeace International added the Atlantic cod to its seafood red list, "a list of fish that are commonly sold in supermarkets worldwide, and which have a very high risk of being sourced from unsustainable fisheries."[53] According to Seafood Watch, cod is currently on the list of fish consumers should avoid.

In summer 2011, a study was announced that showing East Coast cod stocks around Nova Scotia showed promises of recovery starting in 2005, despite earlier thoughts of complete collapse.[52] It said that on the Scotian Shelf after the cod were gone, the small plankton-eating fish (capelin etc.) that the cod ate multiplied to many times their old numbers and ate cod eggs and cod hatchlings, but in the early 2000s collapsed, giving in 2005 a window of opportunity for the cod to start to recover; but more time and studies were needed to study the long-term stability of the stock increase.

In 2011 in a letter to Nature, a team of Canadian scientists reported that cod in the Scotian Shelf ecosystem off Canada showed signs of recovery.[54] Brian Petrie, a team member said, "Cod is about a third of the way to full recovery, and haddock is already back to historical biomass levels."[55] Despite such positive reports, cod landings continued to decline since 2009, according to Fisheries and Oceans Canada statistics through 2012.[16]

In 2015, two reports on cod fishery recovery suggested stocks may have recovered somewhat.[56][2][57]

- A Canadian scientist reported that, cod were increasing in numbers, health, normalizing in maturity and behavior, and offered a promising estimate of increased biomass in particular areas.[2]

- A US report suggested that a failure to consider reduced resilience of cod populations due to increased mortality in warming surface water of the Gulf of Maine had led to overfishing despite regulation. Thus, overestimates of stock biomass due to generalization of local estimates and ignorance of environmental factors in the growth or recovery potential of a cod fishery would lead to mismanagement and further collapse of stocks, through further unsustainable quotas, as in the past.[58][59]

In June 2018, the federal government reduced the cod quota, finding that the cod stocks had fallen again after just two years of fair catches.

Notes

- Kenneth T. Frank; Brian Petrie; Jae S. Choi; William C. Leggett (2005). "Trophic Cascades in a Formerly Cod-Dominated Ecosystem". Science. 308 (5728): 1621–1623. Bibcode:2005Sci...308.1621F. doi:10.1126/science.1113075. PMID 15947186. S2CID 45088691.

- Rose, George A.; Rowe, Sherrylynn (27 October 2015). "Northern cod comeback". Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 72 (12): 1789–1798. doi:10.1139/cjfas-2015-0346. ISSN 0706-652X.

- Hamilton, Lawrence C.; Butler, M. J. (January 2001). "Outport adaptations: Social indicators through Newfoundland's Cod crisis". Human Ecology Review. 8 (2): 1–11.

- Hamilton, L.C.; Haedrich, R.L.; Duncan, C.M. (2004). "Above and below the water: Social/ecological transformation in northwest Newfoundland". Population and Environment. 25 (3): 195–215. doi:10.1007/s11111-004-4484-z. S2CID 189912501.

- Keating, Michael (February 1994). "Media, Fish and Sustainability". Working Paper. Ottawa: National Round Table on Environment and Economy. NDLC: DM621.

- Based on data from the FishStat database FAO.

- "The Starving Ocean". fisherycrisis.com.

- Cochrane (2000), p. 6.

- Dyer, Gwynne (6 February 2013). "Mackerel Wars". Koreatimes. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- Gien (2000), p. 121.

- Mason, Fred (2002). "The Newfoundland Cod Stock Collapse: A Review and Analysis of Social Factors". Electronic Green Journal. UCLA Library (17). doi:10.5070/G311710480. S2CID 152403457. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- MacDowell, L. (2012). "12: Coastal Fisheries". An Environmental History of Canada. Vancouver: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-2103-2.

- Taking Stock [Motion picture]. (1994). Canada.

- Ransom A. Myers; Jeffrey A. Hutchings; Nicholas J. Barrowman (1997). "Why do fish stocks collapse? The example of cod in Atlantic Canada" (PDF). Ecological Applications. 7 (1): 91–106. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(1997)007[0091:WDFSCT]2.0.CO;2. JSTOR 2269409. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-07-13. Retrieved 2019-02-14.

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador: White Paper on Strategies and Programs for Fisheries Development to 1985 (St. John's, 1978), p. 2.

- "2012 Volume Atlantic Coast Commercial Landings, by Region | Fisheries and Oceans Canada". Archived from the original on 2013-12-20. Retrieved 2013-12-27.

- Olsen, E. M.; Heino, M.; Lilly, G. R.; Morgan, M. J.; Brattey, J.; Ernande, B.; Dieckmann, U. (2004). "Maturation trends indicative of rapid evolution preceded the collapse of northern cod". Nature. 428 (6986): 932–935. Bibcode:2004Natur.428..932O. doi:10.1038/nature02430. PMID 15118724. S2CID 315815.

- Swain, D. P.; Sinclair, A. F.; Mark Hanson, J. (2007). "Evolutionary response to size-selective mortality in an exploited fish population". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 274 (1613): 1015–1022. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.0275. PMC 2124474. PMID 17264058.

- Hutchings, J. A.; Fraser, D. J. (2008). "The nature of fisheries- and farming-induced evolution". Molecular Ecology. 17 (1): 294–313. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03485.x. PMID 17784924. S2CID 24481902.

- Pandolfi, J. M. (2009). "Evolutionary impacts of fishing: Overfishing's 'Darwinian debt'". F1000 Biology Reports. 1: 43. doi:10.3410/B1-43. PMC 2924707. PMID 20948642.

- Dolan, et al. (2005), p. 202.

- Kennedy (1997), p. 315.

- Fletcher, Neil. "Will Atlantic cod ever recover?". International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. Archived from the original on 2006-02-14. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- Jeffrey A. Hutchings (2000). "Collapse and recovery of marine fishes" (PDF). Nature. 406 (6798): 882–885. Bibcode:2000Natur.406..882H. doi:10.1038/35022565. PMID 10972288. S2CID 4428364. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-09-27. Retrieved 2019-02-14.

- Comeau, Pauline (July–August 1997). "Confidential report calls Atlantic cod endangered". Canadian Geographic. Vol. 117, no. 4. pp. 18–22. Archived from the original on 2011-11-21. Retrieved 2019-02-17.

- Ottawa Citizen April 18, 1998, p. 1

- "Status of Atlantic Cod, Gadus morhua, in Canada". Archived from the original on 2021-04-15. Retrieved 2019-02-14.

- Bell, K.N.I. "COSEWIC: armpit-length committee". Memorial University of Newfoundland. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- "Letter to Cosewic members". 10 April 1998. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- "Reviews of the Report*: Status of Atlantic Cod, Gadus morhua, in Canada". Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- Bell, K.N.I. "Endangered Cod, Red Herrings, Harps, and Hamster Wheels". Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- Bell, Kim N. I. (1998). "Status of Atlantic Cod, Gadus morhua, in Canada (Status Report commissioned by COSEWIC) [text]". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- Bell, Kim N. I. (1998). "Status of Atlantic Cod, Gadus morhua, in Canada (Status Report commissioned by COSEWIC) [figures]". Archived from the original on 2014-04-01. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- Bell, Kim N. I. "Cod: what happened? Why?". Archived from the original on 2016-03-17. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- Comeau, Pauline (July–August 1998). "New Endangered Species Plan Unveiled - Cod listing shows that mixing politics and science compromises the integrity of decisions, say conservationists". Canadian Geographic. pp. 28–30. Retrieved 2018-06-28.

- Bell, K. N. I. (1998). "An object lesson for demersal African fisheries from the collapse of Canadian Atlantic Cod (Gadus morhua)". In L. Coetzee; J. Gon; C. Kulongowski (eds.). African Fishes and Fisheries - diversity and utilisation. Vol. I (Book of Abstracts). Grahamstown, South Africa, Sept. 13-18 1998. p. 91.

- Snow, C. P. 1962. Science and government (from the Godkin Lectures at Harvard University, 1960). New York: New American Library / Mentor (by arrangement with Harvard University Press). vii+128 pp.

- Jeffrey A. Hutchings; Carl Walters; Richard L. Haedrich (1997). "Is scientific inquiry incompatible with government information control?" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 54 (5): 1198–1210. doi:10.1139/cjfas-54-5-1198. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-13. Retrieved 2019-02-15.

- Harris (1998), p. .

- Kurlansky, Mark (1999). Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World. New York: Vintage. pp. 177–206. ISBN 978-0-09-926870-3. Retrieved 2021-06-16.

- "WWF – No more cod in 15 years, WWF report warns". Worldwildlife.org. 13 May 2004. Archived from the original on 2010-08-10. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- Tisdall, Jonathan (25 April 2002). "Cod not endangered species". Aftenposten.no. Archived from the original on 2008-06-29. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- "Good fishing off Senja". The Royal House of Norway. 15 January 2015.

- Hirsch, Tim (16 December 2002). "Cod's warning from Newfoundland". BBC News. Retrieved 2009-01-13.

- "The Species at Risk Act". Archived from the original on 2013-06-06.

- "WWF – The Barents Sea Cod – the last of the large cod stocks". Panda.org. 10 May 2004. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- Clover, Charles (2004). The End of the Line: How Overfishing is Changing the World and what We Eat. Ebury Press. ISBN 978-0-09-189780-2. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- "Fisheries laying waste to endangered fish stocks". WWF Canada. 20 September 2005. Archived from the original on 2007-03-09. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- "WWF – Cod overfished in the North-West Atlantic despite ban". Panda.org. 27 May 2008. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- Hauge, Marie (9 November 2010). "Raudlista: Friskmelder 15 artar, kritisk for ål og pigghå" [Red List: Announcement for 15 Species, Critical for European Eel and Spiny Dogfish]. Havforskningsinstituttet: Institute of Marine Research (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2013-05-04.

- "What's Holding Back the Cod Recovery?". Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 30 January 2013 [November 1, 2006]. Archived from the original on 2013-06-24. Retrieved 2013-02-06.

- "East Coast cod found to be recovering". CBC News. 27 June 2011.

- "Greenpeace International Seafood Red list". Greenpeace.org. 17 March 2003. Archived from the original on 2008-07-03. Retrieved 2010-09-22.

- Frank, KT; Petrie, B; Fisher, JA; Leggett, WC (2011). "Transient dynamics of an altered large marine ecosystem". Nature. 477 (7362): 86–89. Bibcode:2011Natur.477...86F. doi:10.1038/nature10285. PMID 21796120. S2CID 3116043.

- Coghlan, Andy (28 July 2011). "Canadian cod make a comeback". New Scientist. Retrieved 2011-07-28.

- "The great northern cod comeback". Canadian Science Publishing (NRC Research Press) (Press release). 27 October 2015 – via phys.org.

- "Cod recovery 'quite spectacular,' but George Rose calls for caution". CBC News. 28 October 2015. Retrieved 2023-01-02.

- Goode, Erica (29 October 2015). "Cod's Continuing Decline Linked to Warming Gulf of Maine Waters". The New York Times.

- Pershing, Andrew J.; et al. (13 November 2015). "Slow adaptation in the face of rapid warming leads to collapse of the Gulf of Maine cod fishery". Science. 350 (6262): 809–812. Bibcode:2015Sci...350..809P. doi:10.1126/science.aac9819. PMID 26516197.

References

- Cochrane, Kevern (2000). "Reconciling Sustainability, Economic Efficiency and Equity in Fisheries: the One that Got Away". Fish and Fisheries. 1: 3–21. doi:10.1046/j.1467-2979.2000.00003.x.

- Dolan, Holly; et al. (2005). "Restructuring and Health in Canadian Coastal Communities". EcoHealth. 2 (3): 195–208. doi:10.1007/s10393-005-6333-7. S2CID 9819768.

- Gien, Lan (2000). "Land and Sea Connection: The East Coast Fishery Closure, Unemployment and Health". Canadian Journal of Public Health. 91 (2): 121–124. doi:10.1007/bf03404926. PMC 6980110. PMID 10832177.

- Harris, Michael (1998). Lament for an Ocean: The Collapse of the Atlantic Cod Fishery, a True Crime Story. McClelland & Stewart. ISBN 978-0-7710-3958-4.

- Kennedy, John (1997). "At the Crossroads: Newfoundland and Labrador Communities in a Changing International Context". The Canadian Review of Sociology and Anthropology. 34 (3): 297–318. doi:10.1111/j.1755-618X.1997.tb00210.x.

Further reading

- Dayton, Paul; et al. (1995). "Environmental Effects of Marine Fishing". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 5 (3): 205–232. doi:10.1002/aqc.3270050305.

- Ferguson-Cradler, Gregory (2018). "Fisheries' collapse and the making of a global event, 1950s–1970s". Journal of Global History. 13 (3): 399–424. doi:10.1017/S1740022818000219. hdl:21.11116/0000-0002-72B5-1. S2CID 165758107.

- Holy, Norman (2009). Deserted Ocean: A Social History of Depletion. AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4389-6493-5.

- Hutchings, Jeffrey (1996). "Spatial and Temporal Variation in the Density of Northern Cod a Review of Hypotheses for the Stock's Collapse". Canadian Journal of Aquatic Science. 53 (5): 943–962. doi:10.1139/f96-097.

- Milich, Lenard (1999). "Resource Mismanagement Versus Sustainable Livelihoods: The Collapse of the Newfoundland Cod Fishery". Society and Natural Resources. 12 (7): 625–642. doi:10.1080/089419299279353.

- Stokstad, Erik (7 April 2021). "Massive collapse of Atlantic cod didn't leave evolutionary scars". Science. doi:10.1126/science.abi8780. S2CID 234805414.