Code of Lipit-Ishtar

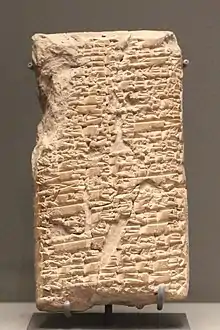

The Code of Lipit-Ishtar is a collection of laws promulgated by Lipit-Ishtar (r. 1934 – 1924 BCE (MC)), a ruler in Lower Mesopotamia. As cuneiform law, it is a legal code written in cuneiform script in the Sumerian language.[2][3]

| Code of Lipit-Ishtar | |

|---|---|

|

It is the second-oldest known extant legal code after the Code of Ur-Nammu. As it is more detailed than that earlier code, it paved the way for the famous later Code of Hammurabi.[4]

History

Historical background

Lipit-Ishtar (r. 1934 – 1924 BCE (MC)) was the fifth king of the Dynasty of Isin, which was founded after the collapse of the Third Dynasty of Ur.[5] His father, Ishme-Dagan, is credited with the restoration of Nippur, an ancient Sumerian city located in today's Iraq.[4] The Dynasty of Isin governed the city of Isin, also located in today's Iraq, and held political power in the cities of Lower Mesopotamia.[5]

Lipit-Ishtar himself is said to have restored peace and is praised for the establishment of a functioning legal system.[4]

Original stele

The original diorite stele inscribed with the code was placed in Nippur. Two pieces of this stele have survived to this day.[4] The American academic Martha Roth notes that during this period a tradition existed to name individual years after notable events that happened in that year and argues that one named year could commemorate the erection of the stele.[5] In its English translation, the year is named as follows:

The year in which Lipit-Ishtar established justice in the lands of Sumer and Akkad.

— Lipit-Ishtar (translated by Martha Roth)

Transmission

The code has been handed down to the present day through various sources. All but two of them stem from Nippur.[4] About half of the code is contained in these sources and thus transmitted. The total length the code is considered to be about the same as that of the later Code of Hammurabi.[4]

Legal contents

The Code of Lipit-Ishtar is similar in structure to the Code of Ur-Nammu, the oldest surviving law code.[4] It has a prologue, which justifies its legal authority, a main body which contains the civil and penal laws governing life and a concluding epilogue.[4]

Prologue

The prologue legitimatizes the legal content of the code. The gods An and Enlil are invoked and it is explained that they have invested Lipit-Ishtar as "the country’s prince" in order to "establish justice in the land, eradicate the cry for justice [...] [and] forcefully restrain crime and violence" so "that Sumer and Akkad [can] be happy".[4] The prologue further informs the reader that Lipit-Ishtar has recently freed slaves from Nippur, Ur, and Isin.[4]

The academic Martha Roth summarizes the prologue as containing self-praise of Lipit-Ishtar, listing all Lower Mesopotamian cities under his rule, and emphasizing his success as a restorer of justice.[5]

Laws

The existing main body consists of almost fifty legal provisions.[4] The first set of them deals with boats. They are followed by provisions on agriculture, fugitive slaves, false testimony, foster care, apprenticeship, marriage and sexual relationships as well as rented oxen.[6] The provisions are all introduced by the Sumerian tukun-be, meaning "if".[6][7] The transmitted provisions do not contain crimes which are punished by death.[7]

The code contains, for example, a provision according to which false accusers have to bear the punishment for the crimes they have alleged.[4][7] All extant provisions of the code are listed by Martha Roth[8] and Claus Wilcke.[9]

Epilogue

The epilogue of the code contains three large lacunae.[4] The remaining parts explain that Lipit-Ishtar executed a divine order and brought justice to his land:[4]

I, Lipit-Ishtar […] silenced crime and violence, made tears, laments and cries for justice taboo, let probity and law shine, made Sumer and Akkad content.

— Lipit-Ishtar (translated by Claus Wilcke)

Furthermore, the erection of the stele is reported upon, and blessings are said to those that who honour the stele and curses inflicted upon those who would venture to desecrate or destroy it.[4][6]

Critical edition and modern translations

No modern critical edition of the code exists.[4] Its last English translation was performed by Martha Roth in 1995.[10] The German academic Claus Wilcke translated it into German in 2014.[11]

References

Citations

- Louvre 2014.

- Sallaberger 2009, p. 7.

- Falkenstein & San Nicolò 1950, p. 103.

- Wilcke 2015.

- Roth 1995, p. 23.

- Roth 1995, p. 24.

- Neumann 2003, p. 83.

- Roth 1995, pp. 26–33.

- Wilcke 2014.

- Wilcke 2014, p. 458.

- Wilcke 2014, pp. 573–606.

Sources

- Falkenstein, A.; San Nicolò, M. (1950). "Das Gesetzbuch Lipit-Ištars von Isin". Orientalia (in German). 19 (1): 103–118. ISSN 0030-5367. JSTOR 43079258.

- Neumann, Hans (2003). Manthe, Ulrich (ed.). Die Rechtskulturen der Antike: vom Alten Orient bis zum Römischen Reich (in German). C. H. Beck. pp. 55–122. ISBN 9783406509155.

- Roth, Martha T. (1995). "Laws of Lipit-Ishtar". Law Collections from Mesopolamia and Asia Minor. Writings from the Ancient World. Vol. 6. Atlanta: Scholars Press. pp. 23–35. ISBN 0-7885-0104-6.

- Sallaberger, Walther (2009). "Der ‚Prolog' des Codex Lipit-Eštar" (PDF). In Achenbach, Reinhard; Arneth, Martin (eds.). Gerechtigkeit und Recht zu üben" (Gen 18,19): Studien zur altorientalischen und biblischen Rechtsgeschichte, zur Religionsgeschichte Israels und zur Religionssoziologie: Festschrift für Eckart Otto zum 65. Geburtstag (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 7–33.

- Wilcke, Claus (2014). "Gesetze in sumerischer Sprache". In Koslova, Natalia; Vizirova, E.; Zólyomi, Gabor (eds.). Studies in Sumerian Language and Literature: Festschrift für Joachim Krecher. Babel und Bibel (in German). Vol. 8. Penn State University Press. doi:10.1515/9781575063553. ISBN 9781575063553.

- Wilcke, Claus (2015). "Laws of Lipit-Ishtar". In Strawn, Brent A. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Bible and Law. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref:obso/9780199843305.001.0001. ISBN 9780199843305.

- "Numéro principal: AO 5473". Louvre (in French). 31 December 2014. Retrieved 21 October 2023.

Further reading

- Kramer, Samuel N. (1955). "Collections of Laws from Mesopotamia and Asia Minor: Lipit-Ishtar Lawcode". In Pritchard, James B. (ed.). Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament with Supplement. Princeton Studies on the Near East. Princeton University Press. doi:10.1515/9781400882762. ISBN 9781400882762.

- Lutzmann, Heiner (1982). "Aus den Gesetzen des Königs Lipit Eschtar von Isin". In Kaiser, Otto (ed.). Rechtsbücher. Texte aus der Umwelt des Alten Testaments (in German). Vol. I. Gütersloher Verlagshaus. pp. 23–31. doi:10.14315/9783641217587. ISBN 978-3-641-21758-7. S2CID 198758881.

- Steele, Francis R. (1947). "The Lipit-Ishtar Law Code". American Journal of Archaeology. 51 (2): 158–164. doi:10.2307/500752. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 500752. S2CID 159785487.

- Steele, Francis R. (1948). "The Code of Lipit-Ishtar". American Journal of Archaeology. 52 (3): 425–450. doi:10.2307/500438. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 500438. S2CID 163318937.

External links

Media related to Code of Lipit-Ishtar at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Code of Lipit-Ishtar at Wikimedia Commons