Irish Gospels of St. Gall

The Irish Gospels of St. Gall or Codex Sangallensis 51 is an 8th-century Insular Gospel Book, written either in Ireland or by Irish monks in the Abbey of St. Gall in Switzerland, where it is now in the Abbey library of St. Gallen as MS 51.[1] It has 134 folios (that is, 268 pages). Amongst its eleven illustrated pages are a Crucifixion, a Last Judgement, a Chi Rho monogram page, a carpet page, and Evangelist portraits.

It is designated by 48 on the Beuron system, and is an 8th-century Latin manuscript of the New Testament. The text, written on vellum, is a version of the old Latin. The manuscript contains the text of the four Gospels on 134 parchment leaves 29.5 cm × 22.5 cm (11.6 in × 8.9 in). It is written in two columns, in Irish semi-uncials. It has been in the St Gall library since at least the 10th century, when it is recorded in the earliest catalogue.[1]

The Latin text of the Gospel of John is a representative of the Western text-type. The text of the other Gospels represents the Vulgate version.[1]

Origin

The Irish Gospels preserved in the Abbey Library are among the finest illustrated manuscripts extant. Because of the square script and the use of minuscule for a liturgical text, O'Sullivan suggested that they might have originated in central Ireland,[2] and Joseph Flahive dates them to around 780.[3] They display a close stylistic affinity with the Faddan More Psalter discovered in 2006, almost miraculously, in a bog near Birr, which is also in the Irish midlands.[2]

The manuscript itself offers no precise information about its place of origin. On page 265, however, there is an entry in a Carolingian minuscule that possibly dates back as far as the second half of the 9th century, apparently imitating the Irish script.[4] This is a sign that the volume had reached the mainland by the 9th or 10th century at the latest and was probably already in St Gallen. Although there is no clear evidence that it had anything to do with the donation of books by the Irish bishop Marcus and his nephew Móengal during the period between 849 and 872, the idea cannot be ruled out.[5]

Content

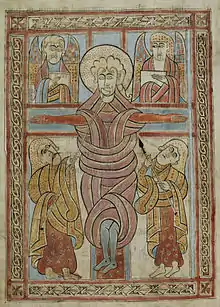

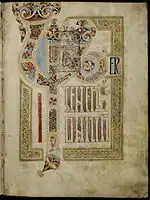

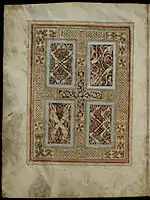

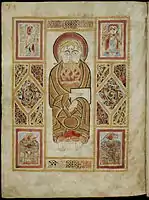

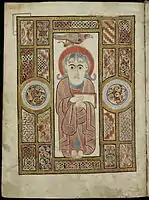

The manuscript contains the four gospels in the form of an Irish hybrid which draws on both Vetus Latina and the Vulgate. Striking from an artistic perspective are the facing pages with which each gospel begins. Each pair consists of an impressive portrait of the evangelist on the left and beautifully crafted incipit on the right.[4] The equilibrium of these double-page compositions is one of the supreme accomplishments of Irish book art. The same quality is evident in a carpet page (p. 6), another decorative initial (p. 7), and depictions of the Crucifixion (p. 266) and the Last Judgment (p. 267) at the end of the book.[4] The initial pages for the Gospels of Mark and John (pp. 78/79 and 208/209) differ in style from the others, so it can be assumed that two different illuminators were at work.[4]

Gallery

"Liber generationis", p 3

"Liber generationis", p 3 Carpet page, p. 6

Carpet page, p. 6 Saint Mark, p. 78

Saint Mark, p. 78 John the Evangelist, p. 208

John the Evangelist, p. 208

References

- Sangallensis 51 at the Stiffsbibliothek St. Gallen

- Farr, Carol Ann (2017). "Reused, rescued, recycled: The art historical and palaeographic contexts of the Irish fragments, St Gallen Codex 1395". In Rachel Moss; Felicity O'Mahony; Jane Maxwell (eds.). An Insular Odyssey: Manuscript culture in early Christian Ireland and beyond. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 175–193. ISBN 978-1-84682-633-7. OCLC 1026385569.

- Bracken, Damian; Flahive, Joseph J., eds. (2009). The St Gall Gospels: Sankt Gallen, Stiftsbibliothek, Codex 51. Cork, Ireland: ArCH Project, School of History, University College Cork. OCLC 1055873029.

- Dora, Cornel; Schnoor, Franziska, eds. (2018). The cradle of European culture: Early medieval Irish book art (Summer exhibition, 13 March until 4 November 2018). Verlag am Klosterhof. ISBN 978-3-906819-30-3. OCLC 1078355376.

- Duft, Johannes. (1954). The Irish miniatures in the Abbey Library of St. Gall. Graf. OCLC 758672107.

Further reading

- Gustav Scherrer, Verzeichniss der Handschriften der Stiftsbibliothek von St. Gallen, Halle 1875, S. 22–23.

External links

- Codex Sangallensis 51 images of the codex at the Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen on e-codices