Coetzee and Matiso

Coetzee v Government of the Republic of South Africa; Matiso and Others v Commanding Officer, Port Elizabeth Prison, and Others[1] is an important case in South African law, with an especial bearing on civil procedure and constitutional law. It concerned the constitutional validity of certain provisions of the Magistrates' Courts Act.[2] It was heard, March 6, 1995, in the Constitutional Court by Chaskalson P, Mahomed DP, Ackermann J, Didcott J, Kentridge AJ, Kriegler J, Langa J, Madala J, Mokgoro J, O'Regan J and Sachs J. They delivered judgment on September 22. The applicant's attorneys were the Legal Resources Centres of Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and Johannesburg. Attorneys for the first and second respondents in the Coetzee application were the State Attorneys of Cape Town and Johannesburg, and Du Plessis & Eksteen for the Association of Law Societies. IMS Navsa SC (with him L. Mpati) appeared for the applicants in both matters, D. Potgieter for the first and second respondents in the Coetzee matter, and JC du Plessis for the Association of Law Societies (as amicus curiae).

| Coetzee v Government of the Republic of South Africa; Matiso v Commanding Officer, Port Elizabeth Prison | |

|---|---|

| |

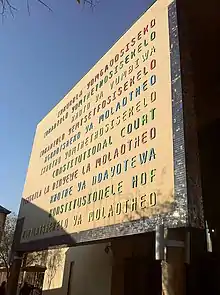

| Court | Constitutional Court of South Africa |

| Full case name | Coetzee v Government of the Republic of South Africa and Others; Matiso and Others v Commanding Officer, Port Elizabeth Prison and Others |

| Decided | 22 September 1995 |

| Citation(s) | [1995] ZACC 7, 1995 (10) BCLR 1382, 1995 (4) SA 631 |

| Case history | |

| Prior action(s) | Referrals from Cape Provincial Division and South Eastern Cape Local Division |

| Court membership | |

| Judges sitting | President Chaskalson, Deputy President Mahomed, Justices Ackermann, Didcott, Kriegler, Langa, Madala, Mokgoro, O'Regan, Sachs, Acting Justice Kentridge |

| Case opinions | |

| Decision by | Kriegler |

Sections 65A to 65M of the Magistrates' Courts Act provided for the imprisonment of judgment debtors in certain circumstances, and were found by the court to be inconsistent with the right to personal freedom provided for in section 11(1) in Chapter 3 of the Interim Constitution. Such provisions were also not capable of being justified as reasonable in terms of the limitation provisions of section 33(1) of the Constitution.[3] It was further impossible, the court found, to excise only those provisions which failed to distinguish between debtors who could not pay and those who could but would not. It was possible, however, to sever from the rest those provisions which made up the option of imprisonment, leaving the balance of the debt-collecting system usefully in force. The court declined to exercise its powers under section 98(5) of the Constitution to keep the provisions in issue alive until Parliament had rectified them, as the debt-collecting system was not dependent upon the imprisonment sanction for its viability, and such provisions were clearly inconsistent with section 11(1) and so manifestly indefensible under section 33(1) that there was no warrant for their retention, even temporarily.

The court also held that, in declaring invalid the provisions of a statute inconsistent with the fundamental rights in chapter 3 of the Constitution, and in severing the invalid provisions from the remainder of the statute, the court should take account of the coming into force of the new Constitution and pay due regard to the values which it requires the court to promote. The court, held Sachs J, should posit a notional, contemporary Parliament dealing with the text in issue when the choice about severance falls to be made.

The case is often cited now for its provision of the test for severability:

Although severability in the context of constitutional law may often require special treatment, in the present case the trite test can properly be applied: if the good is not dependent on the bad and can be separated from it, one gives effect to the good that remains after the separation if it still gives effect to the main objective of the statute. The test has two parts: first, is it possible to sever the invalid provisions and, second, if so, is what remains giving effect to the purpose of the legislative scheme?[4]

The effect of section 232(3) of the Constitution would be to give effect to the principle of "reading down" the provisions in issue, permitting a pared-down construction of the legislation so as to rescue it from a declaration of invalidity. Importantly, however, it did not require restricted interpretation of fundamental rights so as to interfere as little as possible with pre-existing law. Nor was it the function of the court to fill in lacunae in pre-constitutional statutes to save them from invalidity.

As to the applicability of the provisions of section 33(1) of the Constitution, which justify the limitation of a fundamental right, the court set out a two-stage approach. It appeared to the court that the more profound the interest being protected, and the graver the violation, the more stringent should be the scrutiny. The two-stage process was not to be applied mechanically and in a sequentially divided way. The values derived from the concept of an open and democratic society, based on freedom and equality, were to suffuse whole process, such values being normative in the employment of such a process. The court would frequently be required to make difficult value judgments where logic and precedent were of limited assistance.

In interpreting the Constitution, the court would have to consider the area of comparative law. Section 35 of the Constitution was to be understood as requiring the court to give due attention to international experience, with a view to finding principles rather than rigid formulae, and to look for rationales rather than rules.

Judgment

The court found that the following provisions of the Magistrates' Courts Act were inconsistent with the Constitution and declared them invalid, with effect from the date of the order, September 22, 1995:

- the words "why he should not be committed for contempt of court and" in section 65A(1) of the Act;

- sections 65F, 65G and 65H;

- paragraphs (a) and (b) of section 65J(1);

- paragraph (b)(ii) of section 65J(2);

- the following words in paragraph (a) of section 65J(9): "(a) or" and "and may, subject to the provisions of s 65G, be committed for contempt of court for failing to comply with the said order;"

- paragraph (b) of section 65J(9);

- the following words in section 65K(2): "or warrant for the committal of a judgment debtor or a director or an officer of any juristic person or of any sentence imposing a fine on any director or officer representing a judgment debtor who is a juristic person;" and

- section 65L.

The court ordered further that all other provisions of sections 65A-65M of the Act were to remain in force. Consequent upon the declaration of invalidity, it was ordered that, with effect from the date of the order, the committal or continuing imprisonment of any judgment debtor in terms of section 65F or 65G was invalid.[5]

Limitation of rights

Kriegler J held (with Chaskalson P, Mahomed DP, Ackermann J, Didcott J, Kentridge AJ, Langa J, Madala J, Mokgoro J, O'Regan J and Sachs J concurring) that to determine whether or not the right provided for in section 11(1) of the Constitution—"every person shall have the right to freedom and security of the person, which shall include the right not to be detained without trial"—was limited by the various provisions of sections 65A to 65M of the Act, it really would not be necessary to determine the outer boundaries of the right. Nor would it be necessary to examine the philosophical foundation or the precise content of the right. Certainly to put someone in prison is to limit that person's right to freedom; to do so without any criminal charge being levelled, or any trial being held, is manifestly a radical encroachment upon that right.[6]

Accepting that the goal of sections 65A to 65M was to provide a mechanism for the enforcement of judgment debts, and recognising that such goal is a legitimate and reasonable governmental objective, Kriegler J determined that the question was whether or not the means to achieve the goal were reasonable. The answer, clearly, was in the negative.[7] The fundamental reason for this was that the provisions were overbroad. The sanction of imprisonment was ostensibly aimed at the debtor who would not pay, but it was unreasonable in that it also struck at those who could not pay and simply failed to prove this at a hearing, often due to negative circumstances created by the provisions themselves.

There were seven distinct reasons, Kriegler J found, why the provisions were indefensible:

- They allowed persons to be imprisoned without having actual notice either of the original judgment or of the hearing. It was not only theoretically possible, but also quite possible in practice, that the debtor's first notice of the case against him would be when the warrant of committal was executed. In terms of the procedure permitted by the Act and the Rules promulgated thereunder, there need not necessarily have been personal service of any process prior to that.

- Even if a person had notice of the hearing, he could be still imprisoned without knowledge of the possible defences available to him, and accordingly without any attempt to advance any of them. The so-called notice to show cause issued, pursuant to section 65A, did not spell out what the defences were or how they could be established.

- The burden cast on the debtor with regard to inability to pay, although possibly defensible in principle as pertaining to matters peculiarly within his knowledge, was so widely couched that persons genuinely unable to pay were nevertheless struck.

- The provisions of section 65F(3)(c), which spelt out what the debtor must prove, were not only unreasonably wide, but also unreasonably punitive. Whatever might be said about a debtor who wilfully frustrates payment,[8] the nakedly punitive retribution inherent in the provisions of sections 65F(3)(c)(iii) and (iv) could not be justified.

- The provisions allowed a person to be imprisoned without knowing that they had a burden to prove their defence, or how to discharge that burden. It could possibly be contended that the magistrate ought to explain a debtor's rights and duties to an undefended layman, and would probably do so in practice. The fact remained, however, that there was no express obligation on the magistrate to do so.

- It was hardly defensible to treat a civil-judgment debtor more harshly than a criminal. The latter was entitled in terms of section 25(3) of the Constitution to a fair trial with procedural safeguards, including the right to legal assistance at public expense if justice so required. The debtors, who faced months of imprisonment, must fend for themselves as best they could.

- The procedure made no provision for recourse by the debtor to the magistrate or higher authority once an order for committal had been made. Section 65L, which dealt with the release of a debtor from prison, contained no mechanism whereby a debtor, even one against whom a committal order had been made in absentia, was entitled to approach a court for relief. As a result of these defects, the statute swept up those who could not pay with those who could but simply would not. For this reason, the limitation could not be justified as reasonable, as required by section 33(1) of the Constitution.[9]

Severability

As to the question of the severability of the provisions inconsistent with the Constitution from the remaining provisions of sections 65A to 65M, Kriegler J held (Chaskalson P, Mahomed DP, Ackermann J, Didcott J, Kentridge AJ, Langa J, Madala J, Mokgoro J, O'Regan J and Sachs J concurring) that it was impossible to excise only those provisions which failed to distinguish between the two categories of debtors. The reason was that, in order to achieve this, the court would have to engage in the details of law-making, which was a constitutional activity given to the legislatures. It was, however, possible to sever the provisions which made up the option of imprisonment. In so severing such provisions, the court would nevertheless leave intact the object of the statute: to provide a system to assist in the collection of judgment debts. The removal of one of the options available under the system did not render the system contrary to the purpose of the legislative scheme. The infringing provisions could accordingly be severed, and the balance of the system usefully remain in force.[10]

As to the question of whether or not the Court should exercise the power vested in it by section 98(5) of the Constitution, so as to enable the legislature to devise an adequate substitute for the imprisonment option,[11] it was held that it was by no means so that the system was dependent upon the imprisonment sanction for its viability. There were a number of other aids to judgment-debt collection in the system: for example, property attachment and garnishment of wages. In any event, the system was so clearly inconsistent with the right to freedom protected by section 11(1) of the Constitution, and so manifestly indefensible under section 33(1) of the Constitution, that there was no warrant for its retention, even temporarily.[12]

"Draconian effects"

In addition to concurring in the judgment of Kriegler J, Didcott J (Langa J concurring) identified "four draconian effects" of the provisions in issue which rendered the limitation provisions of section 33(1) of the Constitution inapplicable:[13]

- The legislation in question did not insist on the exhaustion by the creditor of his lesser remedies before he threw the book of prospective imprisonment at the debtor.[14]

- It allowed the debtor to be imprisoned without a hearing. The notice issued by the creditor, although served in accordance with the Rules of the Magistrates' Courts, might have been left with somebody else at one of the places permitted for its service, and never have come to the debtor's personal attention. The statute, however, expressly empowered the magistrate to sentence the debtor to imprisonment in his absence, a fate never suffered even by convicted criminals.[15]

- The third obnoxious effect of the legislation related to the absence of the debtor from court, even when he had received the notice and the preceding documents. An explanation of such absence might be the debtor's ignorance of the various defences that were available to him in answering it, in particular the important defence of a poverty afflicting him which was not attributable to his own improvidence. The debtor might labour under the misapprehension that no excuse for his failure to satisfy the judgment would be acceptable, that his imprisonment was an inescapable consequence of the default to which he had to resign himself, and that his attendance at the proceedings could not therefore accomplish anything, for the notice did not inform him of any such excuse; nor was it required to do so.[16]

- A fourth draconian feature of the legislation, described by Didcott J as "ugly," would confront the debtor if, on the other hand, he did appear before the magistrate: the onus then resting on him to prove that he could not pay the judgment debt and bore no blame for his impecuniosity on various grounds listed in section 65F(3)(c) of the Act. The debtor might not manage to establish those facts, although they were the truth, especially when his very poverty had prevented him from hiring a lawyer and he had had to fend for himself in an unfamiliar environment, bewildered by procedures and a forensic methodology to which he was a stranger. The result might well be (and must often have been) that someone who really could not pay, through no fault of his own, went to gaol for his failure to do so.[17]

Didcott J went on to hold

- that the interests of creditors were plainly relevant to any constitutional appraisal of the provisions with the effects set out above;

- that credit played an important part in the modern management of commerce;

- that the rights of creditors to recover the debts owed to them should command the court's respect; and

- that the enforcement of such rights was the legitimate business of South African law.

This did not mean, however, that the interests of creditors should be allowed to ride roughshod over the rights of debtors. The legislation in question permitted that most egregiously in the four respects mentioned above, and was unreasonable and unjustifiable on those cumulatively oppressive scores. Its clear invasion of the right to personal freedom which section 11(1) of the Constitution guaranteed to debtors, as it did to everyone else, was therefore not countenanced by section 33(1).[18]

The bad parts of the statute were not judicially severable from the rest of its provisions that dealt with imprisonment, leaving the court no option but to declare those provisions as a whole to be constitutionally invalid on account of their objectionable overbreadth.[19]

Constitutional protections

Langa J concurred in the judgments of Kriegler J and Didcott J, noting that the difference between the past[20] and the present was that individual freedom and security no longer fell to be protected solely through the vehicle of common-law maxims and presumptions which might be altered or repealed by statute, but which were now protected by entrenched constitutional provisions which neither the legislature nor the executive might abridge. It would accordingly be improper for the court to hold constitutional a system which conferred on creditors the power to consign the person of an impecunious debtor to prison, at will and without the interposition at the crucial ime of a judicial officer. The impugned provisions constituted, for the reasons articulated by Kriegler J and Didcott J, an unreasonable limitation on the "freedom and security" provision in section 11(1) of the Constitution and were therefore clearly unconstitutional.[21]

Civil imprisonment

Sachs J (Mokgoro J concurring) concurred in the judgments of Kriegler J and Didcott J, but held that the contention of the Association of Law Societies—that the court should use its powers to keep the committal proceedings alive pending their rectification by the Legislature—required fuller analysis of the institution of civil imprisonment.[22] On any analysis, using any approach, there could be no doubt that committing someone to prison involves a severe curtailment of that person's freedom and personal security; indeed, the very purpose of committal is to limit the freedom of the person concerned. Given the manifest and substantial invasion of personal freedom thus involved, the real issue that the court had to decide was whether such an infringement could be justified in terms of the general limitations on rights permitted by section 33 of the Constitution.[23]

The only conclusion Sachs J could draw, from such international instruments as the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, the American Convention of Human Rights, the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Protocol 4 of the European Convention and the Explanatory Report on the Fourth Protocol to the European Convention, was that they strongly repudiate the core element of the institution of civil imprisonment: the locking up of people merely because they fail to pay contractual debts. There was, however, a "penumbra" relating to money payments in which imprisonment could be used in appropriately defined circumstances.[24]

Sachs J's conclusions, on this point, were as follows:

When the Law Commission says committal of judgment debtors is an anomaly that cannot be justified and should be abolished; when it is common cause that there is a general international move away from imprisonment for civil debt, of which the present committal proceedings are an adapted relic; when such imprisonment has been abolished in South Africa, save for its contested form as contempt of court in the magistrate's court; when the clauses concerned have already been interpreted by the Courts as restrictively as possible, without their constitutionally offensive core being eviscerated; when other tried and tested methods exist for recovery of debt from those in a position to pay; when the violation of the fundamental right to personal freedom is manifest, and the procedures used must inevitably possess a summary character if they are to be economically worthwhile to the creditor, then the very institution of civil imprisonment, however it may be described and however well directed its procedures might be, in itself must be regarded as highly questionable and not a compelling claimant for survival.

The court, accordingly, should not exercise its discretion under section 98(5) of the Constitution in favour of keeping the institution of imprisonment in sections 65A-65M of the Act alive.[25] Sachs J stressed, however, that this was not to say that there could never be circumstances justifying the use of the back-up of prison to ensure that court orders for payment of judgment debts were obeyed in the same way as other orders. The legislature, if it so chose, would be better placed than the Constitutional Court to do the requisite research, canvass opinions and receive information; it could give full consideration to relevant interrelated factors, such as the proper management of debt collection, the way in which credit was extended, remedies for ensuring fulfilment of obligations and the proper use of court time and prison facilities. It could weigh up all the competing considerations and take account of cost implications and the availability of court and prison officials. If the legislature chose to undertake such an investigation, it would have to operate, Sachs J suggested, within the following framework:

- The process should not permit the imprisonment of persons merely because they were unable to pay their contractual debts.

- The procedures adopted would have to be manifestly fair in all the circumstances.

- Imprisonment, involving as it does a major infringement of the right to personal freedom, would have to be the only reasonably available way of achieving the stated objectives.[26]

Sachs J held further that, in determining whether or not the good could be severed from the bad legislation, and whether or not the legislature would have enacted what survived on its own, the court must take account of the coming into force of the new Constitution, in terms of which the Court received its jurisdiction, and pay due regard to those values which it requires the court to promote. The court must accordingly posit a notional, contemporary Parliament dealing with the text in issue, paying attention both to the constitutional context and to the moment in the country's history at which the choice about severance is to be made.[27]

Sachs J concurred with Kriegler J that the necessary excisions from sections 65A to 65M would leave a statutory provision that was linguistically sustainable, conceptually intact, functionally operational and economically viable.[27] As to the question of whether or not the parts of those provisions which were constitutionally bad should, in the interests of justice and good government, and as intended in section 98(5) of the Constitution, be kept in existence so as to enable Parliament to rectify the legislation, Sachs J found that it had not been established that to end committal proceedings would impair justice or interfere with good government in any drastic or irreparable way. The other remedies provided for in sections 65A to 65M remained available to creditors. There was also no reason for the court to insist on a rapid decision by Parliament, one way or the other, either to accept the continuance of sections 65A to 65M in their truncated form, or else to modify them in the light of the principles enunciated by the Court.[28]

Sachs J accordingly concurred in the formulation of the order in the judgment of Kriegler J as set out above.[28]

Testing constitutionality

Sachs J added that, although notionally the court, in testing the constitutionality of legislative provisions, proceeds in two distinct analytical stages, there is clearly a relationship between the two curial enquiries. The more profound the interest being protected, and the graver the violation, the more stringent the scrutiny. In the end, the court must decide whether, bearing in mind the nature and intensity of the interest to be protected, as well as the degree to which and the manner in which it is infringed, the limitation provided for in section 33 is permissible.[29]

The two-stage process, Sachs J held, should not be approached in a mechanical and sequentially divided way, without paying sufficient attention to the commonalities that run through the two stages. Faithfulness to the Constitution is best achieved, he felt, by locating the two-stage balancing process within a holistic, value-based and case-oriented framework. The values which must suffuse the whole process are derived from the concept of an open and democratic society based on freedom and equality, several times referred to in the Constitution. The notion of an open and democratic society is therefore not merely aspirational or decorative; it is normative, furnishing

- the matrix of ideals within which the court works;

- the source from which the court derives the principles and rules it applies; and

- the final measure it uses for testing the legitimacy of impugned norms and conduct.

It follows, Sachs J determined, from the principles laid down in S v Makwanyane[30] that the Court ought not to engage in purely formal and academic analyses; nor should it simply restrict itself to ad hoc technicism. Rather, it should focus on what has been called the synergetic relation between the values underlying the guarantees of fundamental rights and the circumstances of the particular case. There was no legal yardstick for achieving this. In the end, he predicted, the court will frequently be unable to escape making difficult value judgments, where logic and precedent are of limited assistance. What must be determinative is the Court's judgment, based on an understanding of the values on which South African society is being built, and the interests at stake in the particular case. This judgment cannot be made in the abstract; rather than speak of values as Platonic ideals, the judge must situate his analysis in the facts of the particular case, weighing the different values represented in that context.[31]

In the present matter, the court was called upon to exercise what Sachs J described as a structured and disciplined value judgment, taking account of all the competing considerations that arose in the circumstances of the case, as to whether or not, in the open and democratic society based on freedom and equality contemplated by the Constitution, it was legitimate or acceptable or appropriate to continue to send defaulting judgment debtors to gaol in terms of the procedures set out in sections 65A to 65M of the Magistrates' Courts Act.[31]

Foreign law

Sachs J noted the invitation to the court in section 35 of the Constitution to have regard to international experience where applicable when seeking to interpret provisions relating to fundamental rights. The section is to be understood, he held, as requiring the court to give due attention to such experience, with a view to finding principles rather than extracting rigid formulae, and to look for rationales rather than for rules.[32] With reference to such experience, he discussed in detail the meaning of the word "necessary" in section 33(1) of the Constitution.[33]

Reading down

Section 232(3) of the Constitution, Sachs J observed, provided that, if a restricted interpretation of the law concerned was possible, saving it from unconstitutional inroads into fundamental rights, then that interpretation must be favoured, even if it went against the prima facie meaning of the words in question. This section gave expression to the principle well known in other jurisdictions as "reading down." The section would permit a pared-down construction of legislation so as to rescue it from being declared invalid, but it would not, of course, require a restricted interpretation of fundamental rights so as to interfere as little as possible with pre-existing law. Furthermore, it would not be the function of the court to fill in lacunae in statutes that might not have been visible or regarded as legally significant in the era when parliamentary legislation could not be challenged, but which would become glaringly obvious in the age of constitutional rights. The requirement of reading down would not be an authorisation for reading in.[34]

References

Cases

- African Realty Trust v Sherman 1907 TH 34.

- Board of Regents of State Colleges v Roth 408 US 564 (1972).

- City of Mobile, Alabama v Bolden 446 US 55 (1980).

- Coetzee v Government of the Republic of South Africa; Matiso and Others v Commanding Officer, Port Elizabeth Prison, and Others 1995 (4) SA 631 (CC).

- Edmonton Journal v Alberta AG (1989) 45 CRR 1.

- Erasmus v Thyssen 1994 (3) SA 797 (C).

- Hicks v Feiock 485 US 624 (1988).

- Hofmeyr v Fourie; BJBS Contractors (Pty) Ltd v Lategan 1975 (2) SA 590 (C).

- Hunter et al v Southam Inc (1984) 11 DLR (4th) 641.

- Johannesburg City Council v Chesterfield House (Pty) Ltd 1952 (3) SA 809 (A).

- Kharak Singh v State of Uttar Pradesh and Others [1964] 1 SCR 332.

- Knott v Tuck 1968 (2) SA 495 (D).

- Maneka Gandhi v Union of India AIR 1978 SC 597.

- Matiso v Commanding Officer, Port Elizabeth Prison, and Another 1994 (3) SA 899 (SE) (1994 (3) BCLR 592).

- Matiso and Others v Commanding Officer, Port Elizabeth Prison, and Another 1994 (4) SA 592 (SE).

- Operation Dismantle Inc v The Queen (1985) DLR (4th) 481.

- Quentin's v Komane 1983 (2) SA 775 (T).

- R v France (1993) 16 EHRR 1.

- R v Keegstra (1990) 3 CRR (2d) 193 (SCC) ((1990) 3 SCR 697; 61 CCC (3d) 30).

- R v Morgentaler (1988) 44 DLR (4th) 385.

- R v Oakes (1986) 26 DLR (4th) 200.

- S v Benetti 1975 (3) SA 603 (T).

- S v Chirara; S v Hwengwa and Others; S v Pisaunga; S v Muzondiwa and Others 1990 (2) SACR 356 (ZH).

- S v Khumalo 1984 (4) SA 642 (W).

- S v Lasker 1991 (1) SA 558 (C).

- S v Makwanyane and Another 1995 (3) SA 391 (CC) (1995 (6) BCLR 665).

- S v Motsoesoana 1986 (3) SA 350 (N).

- S v Williams and Others 1995 (3) SA 632 (CC) (1995 (7) BCLR 861).

- S v Zuma and Others 1995 (2) SA 642 (CC) (1995 (4) BCLR 401).

- Silver v United Kingdom (1983) 5 EHRR 347.

- Re Singh and Minister of Employment and Immigration (1985) 17 DLR (4th) 422.

- Thomson Newspapers v Canada [1990] 1 SCR 425.

- Tödt v Ipser 1993 (3) SA 577 (A).

- United States of America v Cotroni (1989) 42 CRR 101.

- Van der Bergh v John Price Estates and Others 1987 (4) SA 58 (SE).

- Woods and Others v Minister of Justice, Legal and Parliamentary Affairs and Others 1995 (1) SA 703 (ZS) (1995 (1) BCLR 56).

- X v Federal Republic of Germany European Commission on Human Rights case No 6699/74, 18 December 1971.

Legislation

- Magistrates' Courts Act 32 of 1944.

Notes

- 1995 (4) SA 631 (CC).

- Act 32 of 1944.

- It was possible that there might be circumstances which justifying the use of imprisonment to ensure that court orders for payment of debts were obeyed, but the legislature was in a better position to research and investigate this and to give full attention to the relevant considerations. In undertaking such investigation, Sachs J recommended, the legislature should ensure that the eventual process should not permit the imprisonment of persons merely because they were unable to pay contractual debts, that the procedures would have to be manifestly fair, and that imprisonment was the only reasonably available way of achieving the stated objectives.

- Para 16.

- Para 19.

- Para 10, read with paras 7 and 8.

- Para 12.

- s 65F(3)(c)(i) and (ii).

- Para 13, read with para 11.

- Para 15 and para 17.

- It had been contended that it would lead to a breakdown of the whole debt-collection procedure if the imprisonment option were to be struck down immediately.

- Para 18.

- Para 21, read with para 20.

- Para 22.

- Para 23.

- Para 24.

- Para 25.

- Para 26.

- Para 27.

- By this he meant the period prior to the commencement of the Constitution

- Paras 35 and 36.

- Para 41.

- Para 44.

- Para 54.

- Paras 70 and 71.

- Para 72.

- Para 75.

- Para 76.

- Para 45.

- 1995 (3) SA 391 (CC).

- Para 46.

- Para 57.

- Paras 57-60.

- Para 62, read with footnote 77.