Collared inca

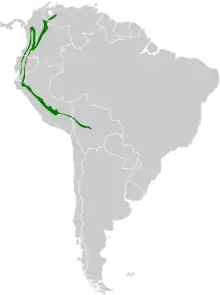

The collared inca (Coeligena torquata) is a species of hummingbird found in humid Andean forests from western Venezuela through Colombia and Ecuador to Peru. It is very distinctive in having a white chest-patch and white on the tail. Like other hummingbirds it takes energy from flower nectar (especially from bromeliads), while the plant benefits from the symbiotic relationship by being pollinated. Its protein source is small arthropods such as insects. It is normally solitary and can be found at varying heights above the ground, often in the open.[3]

| Collared inca | |

|---|---|

_male_in_flight_Caldas.jpg.webp) | |

| male C. t. torquata, Colombia | |

_female_Cundinamarca.jpg.webp) | |

| female C. t. torquata, Colombia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | Strisores |

| Order: | Apodiformes |

| Family: | Trochilidae |

| Genus: | Coeligena |

| Species: | C. torquata |

| Binomial name | |

| Coeligena torquata (Boissonneau, 1840) | |

| |

Taxonomy

The collared inca is a member of subfamily Lesbiinae, the so-called "typical hummingbirds", of family Trochilidae. The family is placed by some taxonomic systems in the order Apodiformes, which contains swifts as well as hummingbirds. Others assign hummingbirds and swifts to order Caprimulgiformes.[4][5][6][7]

Subspecies

Collared incas found in different parts of their range tend to have certain morphological features characteristic of that region, and are considered separate subspecies. The species' taxonomy is unsettled.

The International Ornithological Committee (IOC) and the Clements taxonomy recognize these five subspecies:[5][6][8][9]

- C. t. torquata (Boissonneau, 1840) – Colombia, east slope of Andes in Ecuador, and part of Peru.

- C. t. fulgidigula (Gould, 1854) – West slope in Ecuador. Greener than typical. Patch on male's forehead shimmering blue. Male's chin metallic turquoise.

- C. t. margaretae Zimmer, J.T., 1948 – Central Amazonas Region of Peru to the Pasco Region of Peru. Two-part (shimmering green and blue) forehead patch in male. Female has white and green-spotted chin.

- C. t. insectivora (Tschudi, 1844) – Pasco Region to the Ayacucho Region of Peru.

- C. t. eisenmanni Weske, 1985 – Within a relatively small area to the northwest of Cusco, Peru. Both sexes have some coppery uppertail coverts. Male has black head except for crown. Female has rufous chin.

The South American Classification Committee of the American Ornithological Society (SACC) includes three additional subspecies: C. t. conradii (Bourcier, 1847), C. t. omissa (Zimmer, J.T., 1948), and C. t. inca (Gould, 1852).[4] The IOC and Clements treat conradii as the species green inca and the other two as Gould's inca.[5][6] BirdLife International's Handbook of the Birds of the World (HBW) recognizes the green inca and Gould's inca, and in addition separates C. t. eisenmanni as the species Vilcabamba inca.[7] The SACC is seeking proposals for recognizing these taxa as species.[4]

_male_Caldas.jpg.webp) male C. t. torquata

male C. t. torquata

Colombia female C. t. fulgidigula

female C. t. fulgidigula

Ecuador

Description

10–14 centimetres (3.9–5.5 in) in length, with a rather long (3–3.5 centimetres (1.2–1.4 in)), straight, black beak. Under most lighting conditions Coeligena torquata torquata appears black except for a very large and distinctive white chest-patch. However, in ideal lighting other features can be discerned: a shimmering metallic violet forehead patch in males, white thighs, fleshy-dusky feet, shimmering green throat in males, dull and containing some white in females, and some dark green mixed in with the black of the body. The tail of both genders is black except for white on the basal half of the outer four rectrices, and part of the underside. The female is slightly lighter green overall than the male and has a slightly smaller chest-patch[3][9]

Vocalizations are infrequent. Quiet, low-pitched, reedy whistle "tu-tee." Longer series of "pip... pip..." Very quiet spitting sound when foraging.[9]

Distribution and habitat

Humid subtropical and temperate forest regions, including cloud forests on both slopes of the Andes from Venezuela to Bolivia between 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) and 3,000 metres (9,800 ft), usually above 2,100 metres (6,900 ft) in Ecuador.[3][8] It typically forages below half the height of the canopy, and can most often be found around thickets near the forest edge.[3][9]

It is fairly common throughout most of its range.[3][8] No reasons for concern have been claimed.

Behavior

Diet

Like other hummingbirds, the collared inca obtains most of its energy from nectar, which it drinks while it in turn pollinates the flower, and feeds on insects and other small insect-like arthropods as a source of protein.[9] It seems to prefer epiphytes.[3] It is a solitary trap-liner, meaning that it forages alone by flying a routine route between several flowers.[9]

Breeding

Two single females of other Coeligena species have been observed caring for two offspring each. The nests were 1–2 metres (3.3–6.6 ft) above ground, about 7 centimetres (2.8 in) tall and wide, with an interior cup about 3 centimetres (1.2 in) deep and wide, and were composed of seed down and other materials. The eggs were completely white and measured about 1.5x1 cm. The mother visited once or twice every hour, to feed the young for a period of 9–55 seconds.[10][11]

Status

The IUCN has assessed the collared inca as being of Least Concern. It has a large range but its population size is not known and is believed to be decreasing. No immediate threats have been identified.[1]

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Collared Inca Coeligena torquata". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2016: e.T22726720A94930361. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22726720A94930361.en. Retrieved 1 February 2023.

- "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- Greenfield, P.; Ridgely, R. (2001). The Birds of Ecuador. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press.

- Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, A. Jaramillo, D. F. Lane, J. F. Pacheco, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 30 January 2023. A classification of the bird species of South America. American Ornithological Society. https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm retrieved January 30, 2023

- Gill, F.; Donsker, D.; Rasmussen, P., eds. (January 2023). "Hummingbirds". IOC World Bird List. v 13.1. Retrieved January 30, 2023.

- Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, T. A. Fredericks, J. A. Gerbracht, D. Lepage, S. M. Billerman, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2022. The eBird/Clements checklist of birds of the world: v2022. Downloaded from https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/ retrieved November 10, 2022

- HBW and BirdLife International (2022) Handbook of the Birds of the World and BirdLife International digital checklist of the birds of the world. Version 7. Available at: http://datazone.birdlife.org/userfiles/file/Species/Taxonomy/HBW-BirdLife_Checklist_v7_Dec22.zip retrieved December 13, 2022

- Schulenberg, T.; Stotz, D.; Lane, D.; O'Neill, J.; Parker, T. (2007). Birds of Peru (revised and updated ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Restall, R.; Rodner, C.; Lentino, M. (2006). Birds of Northern South America: An Identification Guide. London: A&C Black.

- Dyrcz, A.; Greeney, H. (2008). "Observations on the Breeding Biology of Bronzy Inca (Coeligena coeligena) in Northeastern Ecuador". Ornitologia Neotropical. 19: 565–571.

- Greeney, H.; Nunnery, T. (2006). "Notes on the breeding of north-west Ecuadorian birds". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 126 (1): 38–45.

External links

- Stamps (for Ecuador) with RangeMap

- Photo-Med Res; Article

- Collared inca photo gallery VIREO