Letter collection

A letter collection consists of a publication, usually a book, containing a compilation of letters written by a real person. Unlike an epistolary novel, a letter collection belongs to non-fiction literature. As a publication, a letter collection is distinct from an archive, which is a repository of original documents.

Usually, the original letters are written over the course of the lifetime of an important individual, noted either for their social position or their intellectual influence, and consist of messages to specific recipients. They might also be open letters intended for a broad audience. After these letters have served their original purpose, a letter collection gathers them to be republished as a group.[1] Letter collections, as a form of life writing, serve a biographical purpose.[2] They also typically select and organize the letters to serve an aesthetic or didactic aim, as in literary belles-lettres and religious epistles.[3] The editor who chooses, organizes, and sometimes alters the letters plays a major role in the interpretation of the published collection.[4] Letter collections have existed as a form of literature in most times and places where letter-writing played a prominent part of public life. Before the invention of printing, letter collections were recopied and circulated as manuscripts, like all literature.[1]

Letter collections in history

Antiquity

In ancient Rome, Cicero (106 – 43 BC) is known for his Letters to Atticus, to Brutus, to friends, and to his brother.[3] Seneca the Younger (c. 5 – 65 CE) and Pliny the Younger (c. 61 – c. 112 CE) both published their own letters. Seneca's Letters to Lucilius are strongly moralizing. Pliny's Epistulae have a self-consciously literary style.[2] Ancient letter collections typically did not organize the letters chronologically.[3]

Early Christianity is also associated with collected and published letters, typically referred to as epistles for their didactic focus. Paul the Apostle (c. 5 – c. 64/67 CE) is known for the Pauline epistles which make up thirteen books of the New Testament.[3]

In late antiquity (340 – 600 CE), letter collections became particularly popular and widespread.[5] Saint Augustine (354 – 430 CE) and Saint Jerome (c. 342-347 – 420 CE) are noted in this period for their prolific and influential theological letters.[1]

Medieval and Renaissance Europe

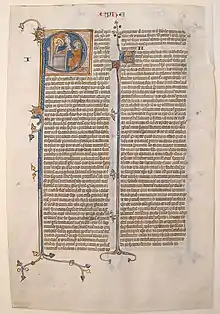

Medieval European letter-writers were heavily influenced by Cicero in the development of rhetorical conventions (ars dictaminis) for letter-writing.[2]

Petrarch (1304 – 1374 CE) added a greater level of personal autobiographical detail in his Epistolae familiares. Erasmus (1466 –1536 CE) and Justus Lipsius (1547 – 1606 CE) also promoted flexibility and enjoyable reading in letter-writing, rather than a rule-focused formula.[2]

Eighteenth-century Europe

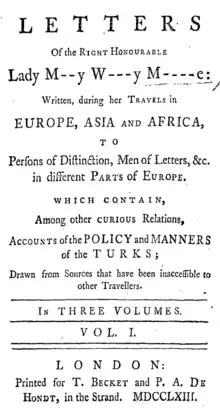

Published letters and diaries were particularly prominent in eighteenth-century British print, sometimes called "the defining genres of the period."[6] Particularly popular were letter collections focused on the private lives of their writers, which would garner praise based on how well they could demonstrate the personal character of the author.[7] Stylistically, eighteenth-century familiar letters were influenced more by the amusing Vincent Voiture (1597 – 1648) than the formal classics of Cicero, Pliny, and Seneca.[7] The letters of Marie de Rabutin-Chantal (1626 – 1696) and her daughter were published beginning in 1725, and widely regarded across Europe as the model for witty, enjoyable letters.[2]

Relationship to authentic letters

Letter collections have not always been considered "literary" texts. In the nineteenth century, scholars like Adolf Deissmann promoted a distinction between a "real missive" and a "literary letter": a "real missive" was a private document focusing solely on a functional communication purpose, whereas a "literary letter" was written with the expectation of a wide audience and carried artistic value. In this distinction, real missives could be used as evidence of factual events, while literary letters required interpretation as works of art. Contemporary scholars, however, see all letters as having both historical information and artistic merit, both of which require careful contextualization.[5]

In eighteenth century Europe, many works were written an epistolary style without having been mailed as real letters: these included scholarly research and travel narratives, as well as epistolary novels.[7] The term "familiar letters" was used to designate letter collections consisting of authentic correspondence which had been written for a private audience prior to publication.[7]

Role of the collector

It was more common for authors to collect their own letters in Latin antiquity than in Greek antiquity. In Latin antiquity, Julius Caesar (100 – 44 BCE) published a self-organized letter collection, which does not survive today. Cicero also mentioned plans to collect his own letters, though he did not do so before his death. Pliny the Younger's letters are the oldest extant letter collection in which the letters were collected by the author himself.[5]

See also

References

- Rosenthal, Joel T. (2014-06-03). "Letters and Letter Collections". Understanding Medieval Primary Sources: Using Historical Sources to Discover Medieval Europe. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-79631-2.

- Bray, Bernard (2001). "Letters: General Survey". In Jolly, Margaretta (ed.). Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms. Translated by Lamontagne, Monique. London: Routledge. pp. 551–553. ISBN 9781579582326.

- Gibson, Roy (2012). "On the Nature of Ancient Letter Collections". The Journal of Roman Studies. 102: 56–78. doi:10.1017/S0075435812000019. ISSN 0075-4358. JSTOR 41724966. S2CID 162653390.

- Grasso, Linda M. (2008). "Reading Published Letter Collections as Literary Texts: Maria Chabot—Georgia O'Keeffe Correspondence, 1941–1949 as a Case Study". Legacy. 25 (2): 239–250. doi:10.1353/leg.0.0033. ISSN 0748-4321. JSTOR 25679657. S2CID 162838092.

- Sogno, Cristiana; Storin, Bradley K.; Watts, Edward J. (2019). "Introduction: Greek and Latin Epistolography and Epistolary Collections in Late Antiquity". Late antique letter collections: a critical introduction and reference guide. Oakland, CA. pp. 1–11. ISBN 978-0-520-30841-1. OCLC 1140699517.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Taylor, Richard C. (2001). "Britain: Restoration and 18th-Century Diaries and Letters". In Jolly, Margaretta (ed.). Encyclopedia of Life Writing: Autobiographical and Biographical Forms. London: Routledge. pp. 137–138–553. ISBN 9781579582326.

- Smith, Amy Elizabeth (1998). "Travel Narratives and the Familiar Letter Form in the Mid-Eighteenth Century". Studies in Philology. 95 (1): 80–86. ISSN 0039-3738. JSTOR 4174599.