Collective–amoeboid transition

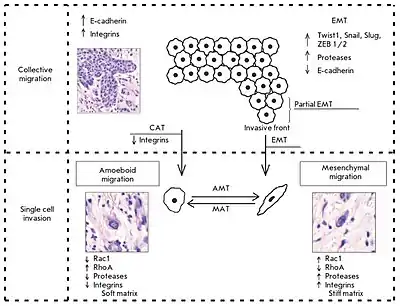

The collective–amoeboid transition (CMT) is a process by which collective multicellular groups dissociate into amoeboid single cells following the down-regulation of integrins.[1][2][3] CMTs contrast with epithelial–mesenchymal transitions (EMT) which occur following a loss of E-cadherin. Like EMTs, CATs are involved in the invasion of tumor cells into surrounding tissues, with amoeboid movement more likely to occur in soft extracellular matrix (ECM) and mesenchymal movement in stiff ECM. Although once differentiated, cells typically do not change their migration mode, EMTs and CMTs are highly plastic with cells capable of interconverting between them depending on intracelluar regulatory signals and the surrounding ECM.[2][1]

CATs are the least common transition type in invading tumor cells, although they are noted in melanoma explants.[4][2]

References

- Krakhmal, N. V.; Zavyalova, M. V.; Denisov, E. V.; Vtorushin, S. V.; Perelmuter, V. M. (2015). "Cancer Invasion: Patterns and Mechanisms". Acta Naturae. 7 (2): 17–28. doi:10.32607/20758251-2015-7-2-17-28. ISSN 2075-8251. PMC 4463409. PMID 26085941.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license. - Friedl, Peter (February 2004). "Prespecification and plasticity: shifting mechanisms of cell migration" (PDF). Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 16 (1): 14–23. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2003.11.001. PMID 15037300. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- Wolf, Katarina; Friedl, Peter (May 2006). "Molecular mechanisms of cancer cell invasion and plasticity: Mechanisms of tumour cell invasion, plasticity, metastasis". British Journal of Dermatology. 154: 11–15. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07231.x. PMID 16712711. S2CID 46262413. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- Gandalovičová, Aneta; Vomastek, Tomáš; Rosel, Daniel; Brábek, Jan (8 February 2016). "Cell polarity signaling in the plasticity of cancer cell invasiveness". Oncotarget. 7 (18): 25022–25049. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.7214. ISSN 1949-2553. PMC 5041887. PMID 26872368. Retrieved 18 September 2023.