Colonisation (biology)

Colonisation or colonization is the process in biology by which a species spreads to new areas. Colonisation often refers to successful immigration where a population becomes integrated into an ecological community, having resisted initial local extinction. In ecology, it is represented by the symbol λ (lowercase lambda) to denote the long-term intrinsic growth rate of a population.

One classic scientific model in biogeography posits that a species must continue to colonize new areas through its life cycle (called a taxon cycle) in order to achieve longevity.[1] Accordingly, colonisation and extinction are key components of island biogeography, a theory that has many applications in ecology, such as metapopulations.

Scale

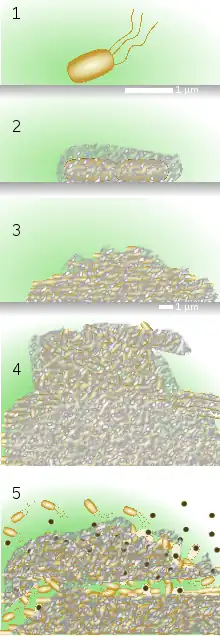

Colonisation occurs on several scales. In the most basic form, as biofilm in the formation of communities of microorganisms on surfaces.[2] In small scales such as colonising new sites, perhaps as a result of environmental change. And on larger scales where a species expands its range to encompass new areas. This can be via a series of small encroachments, such as in woody plant encroachment, or by long-distance dispersal. The term range expansion is also used.[3]

Use

The term is generally only used to refer to the spread of a species into new areas by natural means, as opposed to unnatural introduction or translocation by humans, which may lead to invasive species.

Colonisation events

Large-scale notable pre-historic colonisation events include:

Arthropods

- the colonisation of the earth's land by the first animals, the arthropods. The first fossils of land animals come from millipedes. These were seen about 450 million years ago (Dunn, 2013).

Humans

- the early human migration and colonisation of areas outside Africa according to the recent African origin paradigm, resulting in the extinction of Pleistocene megafauna, although the role of humans in this event is controversial.

Some large-scale notable colonisation events during the 20th century are:

Birds

- the colonisation of the New World by the cattle egret and the little egret

- the colonisation of Britain by the little egret

- the colonisation of western North America by the barred owl[4][5]

- the colonisation of the East Coast of North America by the Brewer's blackbird

- the colonisation-westwards spread across Europe of the collared dove

- the spread across the eastern USA of the house finch

- the expansion into the southern and western areas of South Africa by the Hadeda Ibis

Reptiles

- the colonisation of Anguilla by Green iguanas following a rafting event in 1995

- the colonisation of Burmese pythons into the Florida Everglades. The release of snakes came from the desire to breed them and sell them as exotic pets. As they grew people became unable to care for the animals and began to release them into the Everglades.

Dragonflies

- the colonisation of Britain by the small red-eyed damselfly

Moths

- the colonisation of Britain by Blair's shoulder-knot

References

- Wilson, E.O. (1962) The nature of the Taxon Cycle in Melanesian ant fauna "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-20. Retrieved 2010-09-25.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) The American Naturalist - 1. O’Toole, G., Kaplan, H. B. & Kolter, R. Biofilm Formation as Microbial Development. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 54, 49–79 (2000).

- Yackulic, Charles B.; Nichols, James D.; Reid, Janice; Der, Ricky. 2015. To predict the niche, model colonization and extinction. Ecology. 96(1): 16-23.

- Livezey KB. 2009a. Range expansion of Barred Owls, part I: chronology and distribution. American Midland Naturalist 161:49–56.

- Livezey KB. 2009b. Range expansion of Barred Owls, part 2: facilitating ecological changes. American Midland Naturalist 161:323–349.

Dunn, C. W. (2013). Evolution: Out of the Ocean. Current Biology, 23(6), R241-R243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2013.01.067