Commendation ceremony

A commendation ceremony (commendatio) is a formal ceremony that evolved during the Early Medieval period to create a bond between a lord and his fighting man, called his vassal. The first recorded ceremony of commendatio was in 7th century France, but the relationship of vassalage was older, and predated even the medieval formulations of a noble class. The lord's "man", might be born unfree, but the commendatio freed him.

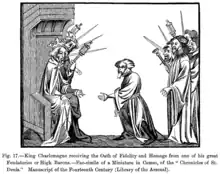

When two men entered into a feudal relationship, they underwent the ceremony. The purpose of the commendation was to make a chosen person a vassal of a lord. The commendation ceremony is composed of two elements, one to perform the act of homage and the other an oath of fealty. In some countries, such as the Kingdom of Sicily, the commendation ceremony came to be referred to as investiture.

Etymology

The word vassal ultimately comes from the PIE root *upo "under". Becoming in the Proto-Celtic language *wasso- "young man, squire," literally "one who stands under," thence into: Welsh gwas "youth, servant," Breton goaz "servant, vassal, man," and Irish foss "servant". The Celtic word was taken into medieval Latin vassallus "man-servant, domestic, retainer." In Old French it became vassal "subject, subordinate, servant" (12c.), and thus into English with this sense.

Act of homage

The would-be vassal appeared bareheaded and weaponless as a sign of his submission to the will of the lord and knelt before him. The vassal would clasp his hands before him in the ultimate sign of submission, the typical Christian prayer pose, and would stretch his clasped hands outward to his lord.

The lord in turn grasped the vassal's hands between his own, showing he was the superior in the relationship, a symbolic act known variously as the immixtio manuum (Latin), Handgang (German), or håndgang (Norwegian).[1] The vassal would announce he wished to become "the man", and the lord would announce his acceptance. The act of homage was complete.

The vassus thus entered into a new realm of protection and mutual services. Through the touching of hands the warrior chief caused to pass from this own body into the body of the vassal something like a sacred fluid, the hail. Made taboo, as it were, the vassal thereupon fell under the charismatic power, pagan in origin, of the lord: his mundeburdium, or mainbour, true power, at once possessive and protective.[2]

The physical position for Western Christian prayer that is thought of as typical today—kneeling, with hands clasped—originates from the commendation ceremony. Before this time, European Christians prayed in the orans, which is the Latin, or "praying" position that people had used in antiquity: standing, with hands outstretched, a gesture still used today in many Christian rituals.

The gesture of homage (though without any feudal significance) survives in the ceremony for conferring degrees at the University of Cambridge.

Eginhard records the solemn commendation ceremony made to Pippin by Tassilo, duke of Bavaria in 757, ("commending himself in vassalage between the hands" (in vasatico se commendans per manus), he swore—and the word used is "sacramenta"—, placing his hands on the relics of the saints, which had apparently been assembled at Compiègne for the solemn occasion, and promised fidelity to the king and to his sons: the relics touched were those of Saint Denis, Saint Rusticus and Saint Éleuthère, Saint Martin and Saint Germain, a daunting array of witnesses. And the men of high birth who accompanied him swore likewise "...and numerous others", Eginhard adds.[3]

Oath of fealty ceremony

The vassal would then place his hands on a Bible, or a saint's relic, and swear he would never injure the lord in any way and to remain faithful.

An example of an oath of fealty (German Lehneid, Dutch leenpligt): "I promise on my faith that I will in the future be faithful to the lord, never cause him harm and will observe my homage to him completely against all persons in good faith and without deceit."

Significance of commendation

Once the vassal had sworn the oath of fealty, the lord and vassal had a feudal relationship.[4]

See also

References

- Duggan, Anne (2000). Nobles and Nobility in Medieval Europe: Concepts, Origins, Transformations, Boydell, Woodbridge, p. 211. ISBN 0-85115-769-6.

- Rouche 1987 p 429

- Eginhard, Annals 757

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 6 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 765.

- Rouche, Michel, "Private life conquers state and society," in A History of Private Life vol I, Paul Veyne, editor, Harvard University Press 1987 ISBN 0-674-39974-9