Red crossbill

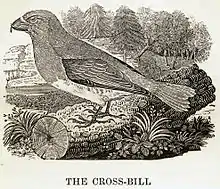

The red crossbill or common crossbill (Loxia curvirostra) is a small passerine bird in the finch family Fringillidae. Crossbills have distinctive mandibles, crossed at the tips, which enable them to extract seeds from conifer cones and other fruits.

| Red crossbill Temporal range: | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Male red crossbill | |

.jpg.webp) | |

| Female red crossbill | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Fringillidae |

| Subfamily: | Carduelinae |

| Genus: | Loxia |

| Species: | L. curvirostra |

| Binomial name | |

| Loxia curvirostra | |

| |

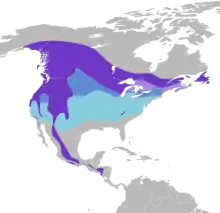

| Range of L. curvirostra Breeding Resident Non-breeding Vagrant (seasonality uncertain) | |

Adults are often brightly coloured, with red or orange males and green or yellow females, but there is wide variation in beak size and shape, and call types, leading to different classifications of variants, some of which have been named as subspecies. The species is known as "red crossbill" in North America and "common crossbill" in Europe.

Description

Crossbills are characterized by the mandibles crossing at their tips, which gives the group its English name. Using their crossed mandibles for leverage, crossbills are able to efficiently separate the scales of conifer cones and extract the seeds on which they feed. Adult males tend to be red or orange in colour, and females green or yellow, but there is much variation.

Identification

The distinctive crossed mandibles eliminate most other species, but this feature is shared by the similar two-barred crossbill, with which it overlaps considerably in range. The two-barred crossbill has two bright white wing bars, while the wings of the red crossbill are entirely brownish-black.

The red crossbill is the only dark-winged crossbill throughout most of its range, but it overlaps at least seasonally with the small ranges of the very similar parrot, Scottish, and Cassia crossbills. These species were formerly considered subspecies of the red crossbill, and though they show very slight differences in bill size and shape, they are very difficult to visually distinguish from the red crossbill and are generally best identified by call. The plumage differences between these four crossbills are negligible, there being more variation between individual birds than between species.[2][3]

Measurements:[4]

- Length: 20 cm

- Weight: 40-53 g

- Wingspan: 27–29 cm

Breeding and irruption

Red crossbills breed in a variety of coniferous forests across North America and Eurasia. Its movements and occurrence are linked very closely to the availability of conifer seeds, its primary food source. They typically nest in late summer (June–September) when the seeds of most conifer species mature, but may nest at any time of year if they locate an area with a suitable cone crop.

This species is considered nomadic and highly irruptive, as conifer seed production may vary considerably year to year and birds disperse widely to breed and forage when the cone crop in their particular vicinity fails. In many areas of their range they are considered irregular because they may be present in certain years and not in others. The various types of red crossbill (see Taxonomy and Systematics) prefer different types of conifers, and therefore may differ in the regularity, timing, and direction of their irruptions. A few populations, such as the Newfoundland crossbill (North American type 8), are resident and do not undertake significant movements. When they are not breeding, the various types of red crossbill may flock together, and may also flock with other species of crossbill.[3][5]

Red crossbill irruptions in the British Isles occur very infrequently, and were remarked upon by writers dating back to the 13th century. These irruptions led in the twentieth century to the establishment of permanent breeding colonies in England, and more recently in Ireland. The first known irruption, recorded in England by the chronicler Matthew Paris, was in 1254; the next, also in England, appears to have been in 1593 (by which time the earlier irruption had apparently been entirely forgotten, since the crossbills were described as "unknown" in England).[6] The engraver Thomas Bewick wrote that "It sometimes is met with in great numbers in this country, but its visits are not regular",[7] adding that many hundreds arrived in 1821. Bewick then cites Matthew Paris as writing "In 1254, in the fruit season, certain wonderful birds, which had never before been seen in England, appeared, chiefly in the orchards. They were a little bigger than Larks, and eat the pippins of the apples [pomorum grana] but no other part of them... They had the parts of the beak crossed [cancellatas] by which they divided the apples as with a forceps or knife. The parts of the apples which they left were as if they had been infected with poison."[7] Bewick further records an account by Sir Roger Twysden for the Additions to the Additamenta of Matt. Paris "that in the apple season of 1593, an immense multitude of unknown birds came into England... swallowing nothing but the pippins, [granella ipsa sive acinos] and for the purpose of dividing the apple, their beaks were admirably adapted by nature, for they turn back, and strike one point upon the other, so as to show... the transverse sickles, one turned past the other."[7]

Taxonomy and systematics

The red crossbill was formally described by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in 1758 in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae under the binomial name Loxia curvirostra.[8] Linnaeus specified the locality as Europe but this was restricted to Sweden by Ernst Hartert in 1904.[9][10] The genus name Loxia is from Ancient Greek loxos, "crosswise"; and curvirostra is Latin for "curved bill".[11]

The red crossbill is in the midst of an adaptive radiation into the niches presented by the various species of conifer.[12] There are about 10 North American and 18 Eurasian types so far identified,[13] with many known to affiliate with a particular conifer species or a suite of similar conifer species. While each type may be seen to feed on many different conifer species when not breeding, each has optimal breeding success only in a particular type of conifer forest. This isolates the populations against interbreeding, which over time has resulted in their diverging genetically, phenotypically, and even speciating. Birds of all types are essentially identical in appearance but have slight differences in their vocalizations. Typically they are identified by their single note "chip" calls, which they give frequently and which differ considerably between types. Often computer analysis is used to distinguish the call types, but experienced observers can learn to separate the more distinctive ones by ear in the field.[3][14]

The different populations of red crossbill are referred to as "types" because they are differentiated by a phenotypic feature (call note) and not all of them have yet been proven to be genetically distinct. Those populations which have been found to be genetically distinct are considered subspecies. Three populations formerly considered to be subspecies of red crossbill are now recognized by most authorities as full species:

- Scottish Crossbill (Loxia scotica) -- Formerly Eurasian type 3C

- Parrot Crossbill (Loxia ptyopsittacus) -- Formerly Eurasian type 2D

- Cassia Crossbill (Loxia sinesciuris) -- Formerly North American type 9

As research into the species has progressed, types are increasingly being found to be genetically distinct and elevated to the subspecies level. It is expected that this trend will continue, and it is also likely that more of these subspecies will eventually be recognized as full species.[3][12][14][15]

Some large-billed, pine-feeding populations currently assigned to this species in the Mediterranean area may possibly be better referred to either the parrot crossbill or to new species in their own right, but more research is needed. These include the Balearic crossbill (L. c. balearica) and the North African crossbill (L. c. poliogyna), feeding primarily on Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis); the Cyprus crossbill (L. c. guillemardi), feeding primarily on European black pine (Pinus nigra); and an as-yet unidentified crossbill with a parrot crossbill-sized bill feeding primarily on Bosnian pine (Pinus heldreichii) in the Balkans. These populations also differ on plumage, with the Balearic, North African and Cyprus subspecies having yellower males, and the Balkan type having deep purple-pink males; this, however, merely reflects the differing anthocyanin content of the cones they feed on, as these pigments are transferred to the feathers.

Diversity

.jpg.webp)

| Distinct Eurasian common crossbill populations | Associated tree species | Summers' list based on calls | The Sound Approach's list based on calls[16] | Call-type, flight call |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balearic crossbill, L. c. balearica | Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) | |||

| North African crossbill, L. c. poliogyna | Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis) | 3E | ||

| Corsican crossbill, L. c. corsicana | European black pine (Pinus nigra) | |||

| Cyprus, Turkey + Caucasus crossbill, L. c. guillemardi | European black pine (Pinus nigra) | 5D | ||

| Crimean crossbill, L. c. mariae | European black pine (Pinus nigra)(?) | |||

| Luzon crossbill, L. c. luzoniensis | Khasi pine (Pinus kesiya) | |||

| Annam crossbill or Da Lat crossbill, L. c. meridionalis | Khasi pine (Pinus kesiya) | |||

| Altai crossbill, L. c. altaiensis | Spruces | |||

| Tian Shan crossbill, L. c. tianschanica | Schrenk's spruce (Picea schrenkiana) | |||

| Himalayan crossbill, L. c. himalayensis | Himalayan hemlock (Tsuga dumosa) | |||

| Japanese crossbill, L. c. japonica | ||||

| Other Eurasian crossbills | ||||

| 1A | 'British crossbill' | Type E - flight call "Chip" | ||

| 1B | 'Parakeet crossbill' | Type X - flight call "Cheep" | ||

| 2B | 'Wandering crossbill' | Type A - flight call "Keep" | ||

| Parrot crossbill, Loxia ptyopsittacus | Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) | 2D | ||

| Scottish crossbill, Loxia scotica | Scots pine, larches, lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) | 3C | ||

| 'Bohemian crossbill' | Type B - flight call "Weet" | |||

| 4E | 'Glip crossbill' | Type C - flight call "Glip" | ||

| 'Phantom crossbill' | Type D - flight call "Jip" | |||

| 'Scarce crossbill' | Type F - flight call "Trip" |

| North American red crossbill subspecies based on biometrics | Jeff Groth's list using call types | Recorded on tree species (Jeff Groth call types) |

|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland crossbill, L. c. percna | Type 8 | black spruce (Picea mariana) |

| Lesser crossbill, L. c. minor | Type 3 | western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) |

| Sitka crossbill, L. c. sitkensis (probably a junior synonym of L. c. minor) | Type 3 | ditto |

| L. c. neogaea | Type 1 | Tsuga species, Picea glauca, Pinus strobus |

| L. c. neogaea | Type 4 | Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) |

| Rocky Mountain crossbill, L. c. benti | Types 2, 7 | Type 2: Rocky Mountains ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa scopulorum) in the west, various Pinus species in the east; Type 7: possibly a general diet |

| Sierra crossbill, L. c. grinnelli | Type 2, 7 | ditto |

| Bendire's crossbill, L. c. bendirei | Type 2, 7 | ditto |

| Mexican crossbill, L. c. stricklandi | Type 6 | pine species in section Trifoliae |

| Central American crossbill, L. c. mesamericana | ||

| Cassia crossbill (described as Loxia sinesciuris in 2009)[17] | Type 9 | isolated population of the lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta latifolia) |

References

- BirdLife International (2017). "Loxia curvirostra". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22720646A111131604. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-1.RLTS.T22720646A111131604.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- "Identification of Scottish and Parrot Crossbills". Scottish Ornithologists' Club. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- "Crossbills of North America: Species and Red Crossbill Call Types". eBird. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- Oiseaux.net. "Bec-croisé des sapins - Loxia curvirostra - Red Crossbill". www.oiseaux.net. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- Benkman, Craig W.; Young, Matthew A. (2020-03-04), Billerman, Shawn M; Keeney, Brooke K; Rodewald, Paul G; Schulenberg, Thomas S (eds.), "Red Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra)", Birds of the World, Cornell Lab of Ornithology, doi:10.2173/bow.redcro.01, retrieved 2021-07-05

- Perry, Richard Wildlife in Britain and Ireland Croom Helm Ltd. London 1978 pp. 134–5.

- Bewick, Thomas (1847). A History of British Birds, volume I, Land Birds (revised ed.). pp. 234–235.. Roger Twysden's Latin note on the 1593 outbreak is given in William Wats's edition of Paris's Chronica Majora (London, 1640).

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 171.

- Hartert, Ernst (1904). Die Vögel der paläarktischen Fauna (in German). Vol. 1. Berlin: R. Friedländer und Sohn. p. 117.

- Paynter, Raymond A. Jr, ed. (1968). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 14. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 288.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London, United Kingdom: Christopher Helm. pp. 125, 231. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Parchman, T. L.; C. W. Benkman (2006). "Patterns of genetic variation in the adaptive radiation of New World crossbills (Aves: Loxia)". Molecular Ecology. 15 (7): 1873–1887. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294x.2006.02895.x. PMID 16689904. S2CID 41768936.

- "Clements Checklist". www.birds.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- "Red Crossbill call types act like species – Sibley Guides". Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- "Red Crossbill Overview, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2021-07-05.

- Magnus S Robb: Introduction to vocalizations of crossbills in north-western Europe

- Benkman, Craig W.; Smith, Julie W.; Keenan, Patrick C.; Parchman, Thomas L.; Santisteban, Leonard (2009). "A New Species of the Red Crossbill (Fringillidae: Loxia) From Idaho". The Condor. 111 (1): 169–176. doi:10.1525/cond.2009.080042. hdl:20.500.11919/2936. S2CID 9166193. Archived from the original on 2019-04-29. Retrieved 2019-09-23.

External links

- Bangs, Outram (12 October 1932). "Birds of Western China Obtained by the Kelly–Roosevelt Expedition". Field Museum of Natural History Publication, Zoological Series. 18 (11): 343–379.

- Ageing and sexing (PDF; 2.9 MB) by Javier Blasco-Zumeta & Gerd-Michael Heinze