Concussions in Australian sport

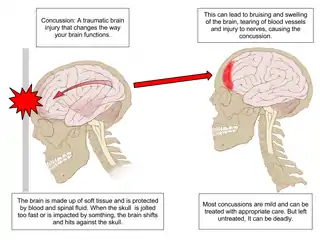

Head injuries in sports of any level (junior, amateur, professional) are the most dangerous kind of injuries that can occur in sport, and are becoming more common in Australian sport. Concussions are the most common side effect of a head injury and are defined as "temporary unconsciousness or confusion and other symptoms caused by a blow to the head." A concussion also falls under the category of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI).[1] Especially in contact sports like Australian rules football and rugby, issues with concussions are prevalent, and methods to deal with, prevent and treat concussions are continuously being updated and researched to deal with the issue. Concussions pose a serious threat to the patients’ mental and physical health, as well as their playing career, and can result in lasting brain damage especially if left untreated. The signs that a player may have a concussion are: loss of consciousness or non-responsiveness, balance problems (unsteadiness on feet, poor co-ordination), a dazed, blank or vacant look and/or confusion and unawareness of their surroundings.[2] Of course the signs are relevant only after the player experiences a blow to the head.

Dangers of concussion

In the short term, concussions do not pose a serious problem and a player suffering may experience: headache, dizziness, loss of memory, blurred vision, confusion, disorientation and /or sensitiveness to bright light and loud noises.[3] However, the real danger occurs after repeated concussions suffered by the same player, if the player returns to play immediately after contracting a concussion or too soon after suffering one. If the player returns to play immediately or too soon after, there is an increased risk of another concussion (which is much more serious) as well as to the rest of the body due to a slower reaction time. The player can also suffer from a number of psychological issues like depression, as well as permanent brain damage and severe brain swelling.[2] A player, regardless of age or level of competition, should not return to play or training following a concussion, without a medical clearance from a registered medical doctors.

AFL

In a high-impact game like Australian Rules Football, head injuries and concussions have always been common, but public awareness has risen over the last decade towards the dangers of continuing to play while suffering from a concussion. It is estimated that there are 5–6 players who suffer a concussion for every 1000 hours spent on the field, meaning there are 6–7 concussions per team during one season.[4] Previously, players at the elite level, either realised they would be pulled out of the game if they were identified as concussed hid the fact from coaches and continued to play, but recently the AFL released new concussion management guidelines to combat the issue. Now, only a medical officer with previous experience in the subject may declare the player fit to play, also the coaches are warned against rushing their players back into the team after suffering a concussion. The guidelines also dictate that immediately, or as soon as possible, after a player suffers a concussion, or is suspected of suffering from one, they must be subjected to a medical assessment after which they may or may not be allowed to return to the field depending on the results.[5] Introduced in 2013 in the AFL, a player suspected of having a concussion must take a 20 minute concussion test. Introduced in 2021 in the AFL, after receiving a concussion, the player must not play in a match for 12 days, unless declared fit to play by an experienced doctor.

The occurrence of concussions in amateur leagues are less common because of the lower impact intensity. However, concussions suffered at amateur levels can at times be more dangerous than those suffered in the AFL because of the inferior resources possessed and in some cases the coaches are not willing to pull a player out of the game, or rest them if they are suffering from a concussion.[6] A study conducted by the Australian Football Injury Prevention Project (AFIPP) in 2002 showed that out of 301 players (who play for amateur clubs in the Melbourne metropolitan area), 14 suffered from a form of head knock, 7 of which resulted in concussion.[7] 18.9% of players participating in the test suffered from concussion, bearing in mind that the sample size is also small.

A separate study showed that out of 1015 Australian Rules Football players tested, 78 of them were concussed, 9 of which were concussed multiple times. The players mental functions were tested at controlled intervals with 38.6% of players still displaying symptoms at 48 hours after being concussed but after 96 hours, only 1.1% displayed any symptoms.[8]

Cricket

Cricket is classified differently to high intensity sports like Australian rules football and rugby, due to the stop-start nature of the game rather than continuous flowing play. However, due to the speed of fast bowlers and the hardness of cricket balls, cricket is still very much a high impact sport. Out of all Australian sporting codes, cricket requires the most protective gear to properly guard batsmen from a variety of injuries that can be afflicted all over the body. The most important piece of protective gear is the helmet, which includes a grill covering the face, to protect batsmen from head injuries. In the most recent Australian tour of the West Indies, now former Australian batsmen Chris Rogers suffered a concussion during training and was ruled out of the test series without playing a match. This has led Cricket Australia to plan out an updated concussion policy and guidelines[9] The principles are based on the International Consensus Conferences on Concussion in Sport (the Zurich Guidelines) and involve the player suspected of being concussed answering a set of questions to determine whether he has to leave the field. While concussion in cricket is considered quite rare due to increasingly safer helmets, the effects can be quite severe. NSW batsmen Ben Rohrer was struck in the head by a cricket ball during a Sheffield Shield match against Victoria in November last year, he recalls his legs feeling like jelly and falling over on the pitch.[10] The most widely known case is the death of NSW batsmen Phillip Hughes who died after being receiving a cricket ball to the head in 2014.

A study conducted with 542 junior cricket players revealed only 13% of injuries were limited to the facial region, and none of them suffered a concussion.[11]

Rugby

Most popular in New South Wales and Queensland, rugby can be classified into two different codes, rugby union and rugby league. Both are played at a very high level of intensity with full contact allowed, and as such has one of the highest concussion rates in the world, let alone Australia. Studies conducted into the incidence of concussion in professional and amateur levels of rugby have revealed that approximately 3.9 concussions per 1000 hours of play occur in professional rugby (1 concussion in every 6 games). Playing at the amateur level, concussion rates are much lower measured at 1 in every 21 matches (1.2 per 1000 hours). This amounts to roughly 5–7 concussions per team per season.[12]

The National Rugby League released a 4 step set of guidelines, in 2012, for all coaches to follow in the case one of their players suffering a concussion during a game. The guidelines detail that the player be given basic first aid before being assessed by a medical officer, they also stress heavily that if the player is determined to be concussed there is no way the player should return to the field. if the concussion is serious, the player should be sent as soon as possible to hospital for medical treatment.[2]

Wearing protective gear, such as a helmet and mouthguard, can reduce the chances of sustaining a concussion.

Concussions in children

The occurrence of concussion in children during sport is significantly more likely compared to other levels of athletes. Roughly 20% of children playing sport are diagnosed with concussion. Despite the lower level of impact compared to the professional or amateur levels, children's neck muscles are quite weak and most lack the awareness and skill level to cushion or prepare themselves for a blow leading to a high concussion rate.[13] The guidelines and protocols for a child suffering a concussion are basically the same as if an adult received one.

For a child diagnosed with a concussion, the real issue is returning to school rather than the sporting field, as a concussion can affect a child's learning ability. A medical clearance is required before a return to school is possible and parents are recommended to properly manage their child through the first 72 hours after experiencing a concussion.[14]

References

- Makdissi, Michael (2010). "Sports Related Concussion – Management in General Practice". Australian Family Physician. 39 (1–2): 12–17. PMID 20369128.

- "Management of Concussion in Rugby League".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "What is concussion?". www.concussioninsportproject.com.au. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Khurana, Vini G.; Kaye, Andrew H. (1 January 2012). "An overview of concussion in sport". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 19 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2011.08.002. PMID 22153800. S2CID 6443393.

- "AFL Community: Concussion". www.aflcommunityclub.com.au. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- Newton, Joshua D.; White, Peta E.; Ewing, Michael T.; Makdissi, Michael; Davis, Gavin A.; Donaldson, Alex; Sullivan, S. John; Seward, Hugh; Finch, Caroline F. (1 January 2014). "Intention to use sport concussion guidelines among community-level coaches and sports trainers". Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 17 (5): 469–473. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2013.10.240. hdl:1959.17/42173. PMID 24252427.

- Braham, R; Finch, CF; McCrory, P (1 January 2004). "The incidence of head/neck/orofacial injuries in non-elite Australian Football". Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 7 (4): 451–453. doi:10.1016/s1440-2440(04)80263-9. PMID 15712501.

- Makdissi, Michael; Darby, David; Maruff, Paul; Ugoni, Antony; Brukner, Peter; McCrory, Paul R. (1 March 2010). "Natural History of Concussion in Sport Markers of Severity and Implications for Management". The American Journal of Sports Medicine. 38 (3): 464–471. doi:10.1177/0363546509349491. ISSN 0363-5465. PMID 20194953. S2CID 2667502.

- "Cricket Australia to roll out new concussion policy across country this summer". Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- "Cricket Australia trialling 'very conservative' guidelines on concussion". Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- Finch, Caroline F.; White, Peta; Dennis, Rebecca; Twomey, Dara; Hayen, Andrew (1 January 2010). "Fielders and batters are injured too: A prospective cohort study of injuries in junior club cricket". Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 13 (5): 489–495. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2009.10.489. PMID 20031485.

- Gardner, Andrew J.; Iverson, Grant L.; Williams, W. Huw; Baker, Stephanie; Stanwell, Peter (20 August 2014). "A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Concussion in Rugby Union". Sports Medicine. 44 (12): 1717–1731. doi:10.1007/s40279-014-0233-3. ISSN 0112-1642. PMID 25138311. S2CID 23808676.

- "Management of Concussion in Children". www.concussioninsportproject.com.au. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- McNamee, M.J.; Partridge, B. & Anderson, L (2015). "Concussion in Sport: Conceptual and Ethical Issues". Kinesiology Review (4 ed.). 4 (2): 190–202. doi:10.1123/kr.2015-0011.