Cabinet of the Confederate States of America

The Cabinet of the Confederate States, commonly called the Confederate cabinet or Cabinet of Jefferson Davis, was part of the executive branch of the federal government of the Confederate States that existed between 1861 and 1865. The members of the Cabinet were the vice-president and heads of the federal executive departments.

| Cabinet of Jefferson Davis | |

| |

.jpg.webp) Last meeting of the Confederate cabinet | |

| Cabinet overview | |

|---|---|

| Formed | February 18, 1861 |

| Dissolved | May 10, 1865 |

| Type | Advisory body |

| Employees | 7 members:

|

| Cabinet executives | |

History

The cabinet was largely modeled on the Cabinet of the United States, with its members overseeing a State Department, Treasury Department, War Department, and Post Office Department. However, unlike the Union, the Confederacy lacked a Department of the Interior, and created a Justice Department (the position of the U.S. Attorney General existed, but the U.S. Department of Justice was only created in 1870, after the end of the Civil War).[1]

Confederate President Jefferson Davis made many of his initial selections to the Cabinet on the basis of political considerations; his choices "Were dictated by the need to assure the various states that their interests were being represented in the government."[2] Moreover, much Confederate talent went into the military rather than the Cabinet, and the cabinet suffered from frequent turnover and reshuffling. Sixteen different men served in the six Cabinet posts during the four years of the Confederacy's existence.[3] The most talented—but also the most unpopular—member of the Cabinet was Judah P. Benjamin.[2][4][5] Among the weakest cabinet secretaries was Treasury Secretary Christopher Memminger, who had little experience with fiscal policy; Memminger was placed at the Treasury by Davis due to the influence of South Carolinians, because Memminger had been an influential supporter of that state's secession.[2] Civil War historian Allen C. Guelzo describes the first Confederate secretaries of war and state, Leroy Pope Walker of Alabama and Robert Toombs of Georgia, respectively—as "brainless political appointees."[2]

The cabinet's performance suffered due to Davis's inability to delegate and propensity to micromanage his Cabinet officers.[6] Davis consulted with the Cabinet frequently—meeting with individual cabinet secretaries almost every day and convening meetings of the full Cabinet two or three times a week—but these meetings, which could stretch to five hours or more, "rarely saw anything accomplished."[7] Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory lamented that "From [Davis's] uncontrollable tendency to digression," cabinet meetings "consumed four or five hours without determining anything."[8] Many of the cabinet members became frustrated, especially the secretaries of war; after concluding "that they could not get along with Davis's constant interference and micromanagement," many resigned.[9] Nine of the eleven Confederate states "had representation in the Cabinet at some point during the life of Confederacy"; only Tennessee and Arkansas never had a Confederate cabinet officer.[10]

The final meeting of the Confederate cabinet took place in Fort Mill, South Carolina, amid the Confederate collapse.[11] Fort Mill was the only place where the full Confederate cabinet met after the fall of Richmond.[12]

Cabinet

| Office | Image | Name | Home state | Dates | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vice President |  |

Alexander H. Stephens | Georgia | February 18, 1861 – May 11, 1865 | |

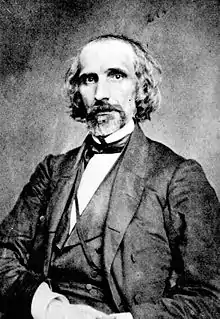

| Secretary of State |  |

Robert Toombs | Georgia | February 25, 1861 – July 25, 1861 | |

.jpg.webp) |

Robert M. T. Hunter | Virginia | July 25, 1861 – February 18, 1862 | ||

|

William M. Browne | Georgia | February 18, 1862 – March 18, 1862 | ||

|

Judah P. Benjamin | Louisiana | March 18, 1862 – May 10, 1865 | ||

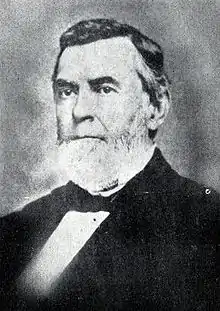

| Secretary of the Treasury | %252C_Secretary_of_Treasury_Confederate_States_of_America.jpg.webp) |

Christopher Memminger | South Carolina | February 25, 1861 – July 18, 1864 | |

|

George Trenholm | South Carolina | July 18, 1864 – April 27, 1865 | ||

|

John H. Reagan | Texas | April 27, 1865 – May 10, 1865 | ||

| Secretary of War |  |

LeRoy Pope Walker | Alabama | February 25, 1861 – September 16, 1861 | |

|

Judah P. Benjamin | Louisiana | September 17, 1861 – March 24, 1862 | ||

|

George W. Randolph | Virginia | March 24, 1862 – November 15, 1862 | ||

|

James Seddon | Virginia | November 21, 1862 – February 5, 1865 | ||

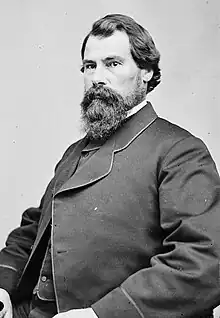

_(14739822666).jpg.webp) |

Major-General John C. Breckinridge |

Kentucky | February 6, 1865 – May 10, 1865 | ||

| Secretary of the Navy |  |

Stephen Mallory | Florida | March 4, 1861 – May 2, 1865 | |

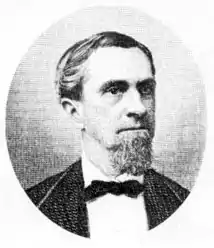

| Postmaster-General |  |

John H. Reagan | Texas | March 6, 1861 – May 10, 1865 | |

| Attorney-General |  |

Judah P. Benjamin | Louisiana | February 25, 1861 – September 17, 1861 | |

|

Wade Keyes | Alabama | September 17, 1861 – November 21, 1861 | ||

|

Thomas Bragg | North Carolina | November 21, 1861 – March 18, 1862 | ||

|

Thomas H. Watts | Alabama | March 18, 1862 – October 1, 1863 | ||

|

Wade Keyes | Alabama | October 1, 1863 – January 2, 1864 | ||

|

George Davis | North Carolina | January 2, 1864 – April 24, 1865 | ||

See also

- Rufus Randolph Rhodes the only head of the Confederate Patent Office

References

- The Library of Congress Civil War Desk Reference (eds. Margaret E. Wagner, Gary W. Gallagher & Paul Finkelman: Simon & Schuster, 2012), p. 161.

- Allen C. Guelzo, Fateful Lightning: A New History of the Civil War and Reconstruction (Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 361.

- Exploring American History: From Colonial Times to 1877 (Vol. 3: eds. Tom Lansford & Thomas E. Woods: Marshall Cavendish, 2008), p. 241.

- Dennis L. Peterson, Confederate Cabinet Departments and Secretaries (MacFarland, 2016), pp. 141-42.

- Bell Irvin Wiley, Embattled Confederates: An Illustrated History of Southerners at War (Harper & Row, 1964), p. 19.

- Peterson, pp. 12, 18, 24, 91, 127, 150.

- Peterson, p. 18.

- Geoffrey C. Ward & Kenneth Burns, The Civil War: The Complete Text of the Bestselling Narrative History of the Civil War--Based on the Celebrated PBS Television Series (Vintage Books, 1990),p. 162.

- Peterson, p. 24.

- Peterson, p. 13.

- Clint Johnson, Touring the Carolinas' Civil War Sites, 2nd ed. (John F. Blair, Publisher: 2011), p. 109.

- James E. Walmsley, The Last Meeting of the Confederate Cabinet (The Mississippi Valley Historical Review, 1919).