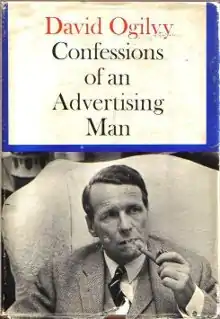

Confessions of an Advertising Man

In Confessions of an Advertising Man, David Ogilvy shares his lessons from advertising consumer brands worldwide in the fifties and sixties in an eleven-chapter playbook of more than two hundred rules that cover corporate and subject matter aspects, the latter focused on the copywriting and illustrations of advertising campaigns for printed media. Two editions were released, in 1963 and 1988.

| |

| Author | David Ogilvy |

|---|---|

| Subject | Advertising |

| Publisher | Atheneum |

Publication date | August 1963 |

| ISBN | 1-904915-01-9 |

Summary of the 1963 edition

I - Managing an advertising agency is like managing any other creative business. Ogilvy articulates the ten anchors that underpinned the corporate culture of his agency’s 497 employees in 1963: they work hard, combine intelligence with intellectual honesty, put passion in what they do, do not soak up to their bosses, are self-confident, do not hire their spouses but future successors who they build up, have gentle manners, are well-organised and deliver work on time.

II - Ogilvy founded his agency in 1948 with $6,000 and the financial backing of his brother, Francis, then MD at Mather & Crowther, an advertising agency in London. In 1963, Ogilvy, Benson & Mather billed for $55m and had nineteen clients, of which Chase, Standard Oil (NJ), Shell, KLM, Rolls-Royce and Guinness. All had good products, which Ogilvy was proud to advertise and all gave the agency an opportunity to make a profit or create great campaigns.

III - Agencies have better chances of keeping their clients, if they put their best people on serving them, instead of chasing prospects. They are vigilant about the quality of client relationships at all hierarchical levels, if they invest in testing new campaigns and using clients’ products. Agencies should refuse to take companies that fire their agencies frequently and actively resign accounts who dictate their campaigns, are unprofitable or whose products get worse.

IV - Ogilvy also offers fifteen rules for businesses who want to be good clients of agencies. His main advice is to emancipate agencies from fear, tolerate genius, not bog them down with committees but brief their agency very thoroughly.

V - Great campaigns, those that drive product sales without drawing attention to themselves, build on the specific knowledge acquired by mail-order advertisers, department stores, research departments and direct market experience. Ogilvy encapsulates them into eleven great campaign commandments. There is no great campaign without a Big Idea. Ogilvy strongly advises to demonstrate the benefit to the customer specifically and factually.

VI - Potent copy results from being very disciplined in the writing of headlines and body copies. Doing so Ogilvy delivered his “best headline ever”,[1] for Rolls-Royce: “At Sixty Miles an Hour, the Loudest Noise in the New Rolls-Royce Comes from the electric clock”; it was followed by a 719-word body copy, which he later increased to 1,400 following positive readers’ reactions to the first.

VII - The same artistic discipline applied to illustrations can arouse reader’s curiosity, such as the eye patch of the Hathaway man. Ogilvy distils his extensive know-now through forty-one specific commandments such as those three: i) photographs sell more than illustrations (because they are closer to reality and therefore more believable), ii) people are more attracted to faces of the same sex than the opposite, iii) never set the copy in reverse (white type on a black background).

VIII - As television was still a rather new medium in 1963, this chapter is short: four pages vs twenty-three devoted to advertising in printed media.

IX - These rules are further refined to the advertisement of food, travel and drug products. For instance, good food advertising is centred around the appetite appeal, makes food the hero, shows it in colour with a readable recipe.

X - Ogilvy lists twenty behaviours that will get young people to climb the hierarchical ladder faster than their fellow colleagues. Being ambitious without being aggressive, working hard to become an expert of their clients’ industry, preferring a speciality to account management and rising to the occasion will all lead them faster to the top of the tree.

XI - The book ends by discussing whether advertising should be abolished. Ogilvy’s own experience is that informative advertising is more profitable than “combative” advertising and although his views are pro-business he closes by noting that "advertising [...] should not be abolished [...] but reformed".[2]

Additions of the 1988 edition

In his foreword, Sir Alan Parker recalls he worked at Ogilvy in the mid sixties. Back then the Confessions were required reading and the equivalent of Mao’s Little Red Book. Undoubtedly, the book has made the profession cool and almost respectable.

In the Story Behind this Book, Ogilvy summarises a quarter of a century of growth since the first edition with two numbers: his agency has grown sixtyfold and the Confessions have sold a million copies in fourteen languages. David Ogilvy calls out three specific rules of the 1963 edition which have been invalidated by research and market experiments, and points out that the chapter on TV commercials is inadequate. However, the nine founding principles of Ogilvy & Matther’s corporate culture that were described in the 1963 edition remain valid. The most important of them is probably the first one: “We sell - or else.”[3]

References

- Ogilvy, David (2013). Confessions of an Advertising Man (1988 ed.). London: Southbank Publishing. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-904915-37-9.

- Ogilvy, David (2013). Confessions of an Advertising Man (1988 ed.). London: Southbank Publishing. p. 180. ISBN 978-1-904915-37-9.

- Ogilvy, David (2013). Confessions of an Advertising Man (1988 ed.). London: Southbank Publishing. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-904915-37-9.