Posterior urethral valve

Posterior urethral valve (PUV) disorder is an obstructive developmental anomaly in the urethra and genitourinary system of male newborns.[1] A posterior urethral valve is an obstructing membrane in the posterior male urethra as a result of abnormal in utero development. It is the most common cause of bladder outlet obstruction in male newborns. The disorder varies in degree, with mild cases presenting late due to milder symptoms. More severe cases can have renal and respiratory failure from lung underdevelopment as result of low amniotic fluid volumes, requiring intensive care and close monitoring.[2] It occurs in about one in 8,000 babies.[3]

| Posterior urethral valve | |

|---|---|

| |

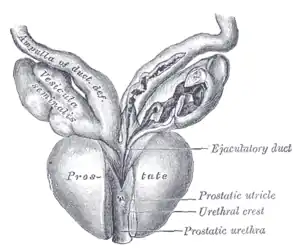

| Vesiculæ seminales and ampullæ of ductus deferentes, seen from the front. Posterior urethral valves are at the dorsal aspect (back) of the prostatic urethra. | |

| Specialty | Urology |

Presentation

PUV can be diagnosed before birth, or even at birth when the ultrasound shows that the male baby has a hydronephrosis. Some babies may also have oligohydramnios due to the urinary obstruction.[4] The later presentation can be a urinary tract infection, diurnal enuresis, or voiding pain.

Diagnosis

Abdominal ultrasound is of some benefit, but not diagnostic. Features that suggest posterior urethral valves are bilateral hydronephrosis, a thickened bladder wall with thickened smooth muscle trabeculations, and bladder diverticula.

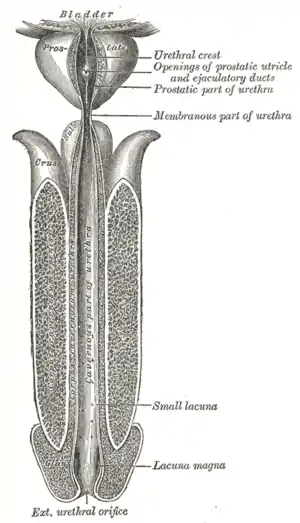

Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) is more specific for the diagnosis. Normal plicae circularis are variable in appearance and often not seen on normal VCUGs. PUV on voiding cystourethrogram is characterized by an abrupt tapering of urethral caliber near the verumontanum, with the specific level depending on the developmental variant. Vesicoureteral reflux is also seen in over 50% of cases. Very often the posterior urethra maybe dilated thus making the abrupt narrowing more obvious. the bladder wall may show trabeculations or sacculations or even diverticuli.

Diagnosis can also be made by cystoscopy, where a small camera is inserted into the urethra for direct visualization of the posteriorly positioned valve. A limitation of this technique is that posterior valve tissue is translucent and can be pushed against the wall of the urethra by inflowing irrigation fluid, making it difficult to visualize. Cystoscopy may also demonstrate the bladder changes.

Centers in Europe and Japan have also had excellent results with cystosonography, although it has not been approved for use in the United States yet.[5]

Classification

Posterior urethral obstruction was first classified by H. H. Young in 1919. The verumontanum, or mountain ridge, is a distinctive landmark in the prostatic urethra, important in the systemic division of posterior valve disorders:

- Type I - Most common type; due to anterior fusing of the plicae colliculi, mucosal fins extending from the bottom of the verumontanum distally along the prostatic and membranous urethra[6]

- Type II - Least common variant; vertical or longitudinal folds between the verumontanum and proximal prostatic urethra and bladder neck

- Type III - Less common variant; a disc of tissue distal to verumontanum, also theorized to be a developmental anomaly of congenital urogenital remnants in the bulbar urethra

Dewan has suggested that obstruction in the posterior urethra is more appropriately termed congenital obstructions of the posterior urethral membrane (COPUMs), a concept that has come from an in-depth analysis of the historical papers, and evaluation of patients with a prenatal diagnosis that has facilitated video recording of the uninstrumented obstructed urethra.[7] The congenital obstructive lesions in the bulbar urethra, named Type III Valves by Young in 1919, have been eponymously referred to as Cobb's collar or Moorman's ring.[8] For each of the COPUM (Posterior Urethra) and Cobb's (Bulbar Urethra) lesions, the degree of obstruction can be variable, consistent with a variable expression of the embryopathy.[9] The now nearly one hundred year old nomenclature of posterior urethral valves was based on limited radiology and primitive endoscopy, thus a change COPUM or Cobb's has been appropriate.

Treatment

If suspected antenatally, a consultation with a paediatric surgeon/ paediatric urologist maybe indicated to evaluate the risk and consider treatment options.

The most important first treatment in a newborn baby boy is to relieve the bladder with urethral catheter or suprapubic drainage.[10]

Treatment is by endoscopic valve ablation. Fetal surgery is a high risk procedure reserved for cases with severe oligohydramnios, to try to limit the associated lung underdevelopment, or pulmonary hypoplasia, that is seen at birth in these patients. The risks of fetal surgery are significant and include limb entrapment, abdominal injury, and fetal or maternal death. Specific procedures for in utero intervention include infusions of amniotic fluid, serial bladder aspiration, and creating a connection between the amniotic sac and the fetal bladder, or vesicoamniotic shunt.[5]

There are three specific endoscopic treatments of posterior urethral valves:

- Vesicostomy followed by valve ablation - a stoma, or hole, is made in the urinary bladder, also known as low diversion, after which the valve is ablated and the stoma is closed.

- Pyelostomy followed by valve ablation - stoma is made in the pelvis of the kidney as a slightly high diversion, after which the valve is ablated and the stoma is closed

- Primary (transurethral) valve ablation - the valve is removed through the urethra without creation of a stoma

The standard treatment is primary (transurethral) ablation of the valves.[11] Urinary diversion is used in selected cases,[11] and its benefit is disputed.[12][13]

Following surgery, the follow-up in patients with posterior urethral valve syndrome is long term, and often requires a multidisciplinary effort between paediatric surgeons/ paediatric urologists, paediatric nephrologists, pulmonologists, neonatologists, radiologists and the family of the patient. Care must be taken to promote proper bladder compliance and renal function, as well as to monitor and treat the significant lung underdevelopment that can accompany the disorder. Definitive treatment may also be indicated for the vesico-ureteral reflux.

Female homolog

The female homolog to the male verumontanum from which the valves originate is the hymen.

References

- Manzoni C, Valentini A (2002). "Posterior urethral valves". Rays. 27 (2): 131–4. PMID 12696266.

- "Emedicine - Posterior urethral valves - overview and treatment". Emedicine. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- "Posterior urethral valves - Disease Information". Children's hospital, Boston. Archived from the original on May 19, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- Klaassen, I.; Neuhaus, T. J.; Mueller-Wiefel, D. E.; Kemper, M. J. (2006). "Antenatal oligohydramnios of renal origin: long-term outcome". Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 22 (2): 432–439. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfl591. ISSN 0931-0509. PMID 17065192.

- "Emedicine - Posterior Urethral Valves - Diagnosis and Treatment". Emedicine. Archived from the original on July 8, 2012. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- "Nationwide Children's Hospital, Radiology - Posterior urethral valves". Nationwide Children's Hospital. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- Dewan, Paddy (2014-07-19). "Posterior Urethral Obstruction: COPUM". Bangladesh Journal of Endosurgery. 2 (1): 29–32. doi:10.3329/bje.v2i1.19590. ISSN 2306-4390.

- "Nationwide Children's Hospital, Radiology - Cobb's Collar". Nationwide Children's Hospital. Retrieved July 26, 2010.

- Dewan, PA; Goh, DW (1995). "Variable expression of the congenital membrane of the posterior urethra". Urology. 45 (3): 507–509 1995. doi:10.1016/s0090-4295(99)80024-7. PMID 7879340.

- Rink, Richard C.; Mouriquand, Pierre D. E. (2010). Pediatric Urology. ISBN 978-1-4160-3204-5.

- Warren J, Pike JG, Leonard MP (April 2004). "Posterior urethral valves in Eastern Ontario - a 30 year perspective". Can J Urol. 11 (2): 2210–5. PMID 15182412.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kim YH, Horowitz M, Combs A, Nitti VW, Libretti D, Glassberg KI (August 1996). "Comparative urodynamic findings after primary valve ablation, vesicostomy or proximal diversion". J. Urol. 156 (2 Pt 2): 673–6. doi:10.1097/00005392-199608001-00028. PMID 8683757.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Smith GH, Canning DA, Schulman SL, Snyder HM, Duckett JW (May 1996). "The long-term outcome of posterior urethral valves treated with primary valve ablation and observation". J Urol. 155 (5): 1730–4. doi:10.1016/S0022-5347(01)66186-X. PMID 8627873.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)