Pilus

A pilus (Latin for 'hair'; PL: pili) is a hair-like appendage found on the surface of many bacteria and archaea.[1] The terms pilus and fimbria (Latin for 'fringe'; plural: fimbriae) can be used interchangeably, although some researchers reserve the term pilus for the appendage required for bacterial conjugation. All conjugative pili are primarily composed of pilin – fibrous proteins, which are oligomeric.

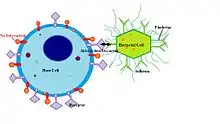

Dozens of these structures can exist on the bacterial and archaeal surface. Some bacteria, viruses or bacteriophages attach to receptors on pili at the start of their reproductive cycle.

Pili are antigenic. They are also fragile and constantly replaced, sometimes with pili of different composition, resulting in altered antigenicity. Specific host responses to old pili structures are not effective on the new structure. Recombination between genes of some (but not all) pili code for variable (V) and constant (C) regions of the pili (similar to immunoglobulin diversity). As the primary antigenic determinants, virulence factors and impunity factors on the cell surface of a number of species of Gram negative and some Gram positive bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonadaceae, and Neisseriaceae, there has been much interest in the study of pili as organelle of adhesion and as vaccine components. The first detailed study of pili was done by Brinton and co-workers who demonstrated the existence of two distinct phases within one bacterial strain: pileated (p+) and non-pileated)[2]

Types by function

A few names are given to different types of pili by their function. The classification does not always overlap with the structural or evolutionary-based types, as convergent evolution occurs.[3]

Conjugative pili

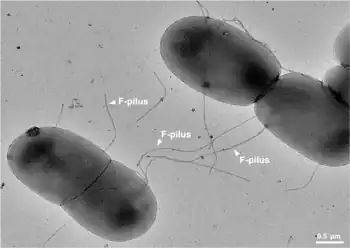

Conjugative pili allow for the transfer of DNA between bacteria, in the process of bacterial conjugation. They are sometimes called "sex pili", in analogy to sexual reproduction, because they allow for the exchange of genes via the formation of "mating pairs". Perhaps the most well-studied is the F-pilus of Escherichia coli, encoded by the F sex factor.

A sex pilus is typically 6 to 7 nm in diameter. During conjugation, a pilus emerging from the donor bacterium ensnares the recipient bacterium, draws it in close, and eventually triggers the formation of a mating bridge, which establishes direct contact and the formation of a controlled pore that allows transfer of DNA from the donor to the recipient. Typically, the DNA transferred consists of the genes required to make and transfer pili (often encoded on a plasmid), and so is a kind of selfish DNA; however, other pieces of DNA are often co-transferred and this can result in dissemination of genetic traits throughout a bacterial population, such as antibiotic resistance. The connection established by the F-pilus is extremely mechanically and thermochemically resistant thanks to the robust properties of the F-pilus, which ensures successful gene transfer in a variety of environments. [5] Not all bacteria can make conjugative pili, but conjugation can occur between bacteria of different species.

Hyperthermophilic archaea encode pili structurally similar to the bacterial conjugative pili.[6] However, unlike in bacteria, where conjugation apparatus typically mediates the transfer of mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids or transposons, the conjugative machinery of hyperthermophilic archaea, called Ced (Crenarchaeal system for exchange of DNA)[7] and Ted (Thermoproteales system for exchange of DNA),[6] appears to be responsible for the transfer of cellular DNA between members of the same species. It has been suggested that in these archaea the conjugation machinery has been fully domesticated for promoting DNA repair through homologous recombination rather than spread of mobile genetic elements.[6]

Fimbriae

Fimbria (Latin for 'fringe', PL: fimbriae) is a term used for a short pilus that is used to attach the bacterium to a surface, sometimes also called an "attachment pilus".[8] The term "fimbria" can refer to many different (structural) types of pilus, as many different types of pili have been used for adhesion, a case of convergent evolution.[3] The Gene Ontology system does not treat fimbriae as a distinct type of appendage, using the generic pilus (GO:0009289) type instead.

This appendage ranges from 3–10 nanometers in diameter and can be as much as several micrometers long. Fimbriae are used by bacteria to adhere to one another and to adhere to animal cells and some inanimate objects. A bacterium can have as many as 1,000 fimbriae. Fimbriae are only visible with the use of an electron microscope. They may be straight or flexible.

Fimbriae possess adhesins which attach them to some sort of substratum so that the bacteria can withstand shear forces and obtain nutrients. For example, E. coli uses them to attach to mannose receptors.

Some aerobic bacteria form a very thin layer at the surface of a broth culture. This layer, called a pellicle, consists of many aerobic bacteria that adhere to the surface by their fimbriae. Thus, fimbriae allow the aerobic bacteria to remain both on the broth, from which they take nutrients, and near the air.

Fimbriae are required for the formation of biofilm, as they attach bacteria to host surfaces for colonization during infection. Fimbriae are either located at the poles of a cell or are evenly spread over its entire surface.

This term was also used in a lax sense to refer to all pili, by those who use "pilus" to specifically refer to sex pili.[9]

Types by assembling system or structure

Transfer

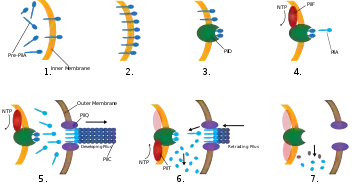

The Tra (transfer) family includes all known sex pili (as of 2010). They are related to the type IV secretion system (T4SS).[3] They can be classified into the F-like type (after the F-pilus) and the P-like type. Like their secretion counterparts, the pilus injects material, DNA in this case, into another cell.[10]

Type IV pili

Some pili, called type IV pili (T4P), generate motile forces.[12] The external ends of the pili adhere to a solid substrate, either the surface to which the bacterium is attached or to other bacteria. Then, when the pili contract, they pull the bacterium forward like a grappling hook. Movement produced by type IV pili is typically jerky, so it is called twitching motility, as opposed to other forms of bacterial motility such as that produced by flagella. However, some bacteria, for example Myxococcus xanthus, exhibit gliding motility. Bacterial type IV pili are similar in structure to the component proteins of archaella (archaeal flagella), and both are related to the Type II secretion system (T2SS);[13] they are unified by the group of Type IV filament systems. Besides archaella, many archaea produce adhesive type 4 pili, which enable archaeal cells to adhere to different substrates. The N-terminal alpha-helical portions of the archaeal type 4 pilins and archaellins are homologous to the corresponding regions of bacterial T4P; however, the C-terminal beta-strand-rich domains appear to be unrelated in bacterial and archaeal pilins.[14]

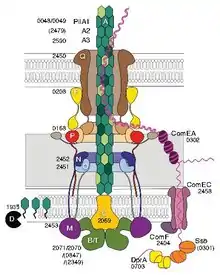

Genetic transformation is the process by which a recipient bacterial cell takes up DNA from a neighboring cell and integrates this DNA into its genome by homologous recombination. In Neisseria meningitidis (also called meningococcus), DNA transformation requires the presence of short DNA uptake sequences (DUSs) which are 9-10 monomers residing in coding regions of the donor DNA. Specific recognition of DUSs is mediated by a type IV pilin.[15] Menningococcal type IV pili bind DNA through the minor pilin ComP via an electropositive stripe that is predicted to be exposed on the filament's surface. ComP displays an exquisite binding preference for selective DUSs. The distribution of DUSs within the N. meningitides genome favors certain genes, suggesting that there is a bias for genes involved in genomic maintenance and repair.[16][17]

This family was originally identified as "type IV fimbriae" by their appearance under the microscope. This classification survived as it happens to correspond to a clade.[18]

Type 1 fimbriae

Another type are called type 1 fimbriae.[19] They contain FimH adhesins at the "tips". The chaperone-usher pathway is responsible for moving many types of fimbriae out of the cell, including type 1 fimbriae[20] and the P fimbriae.[21]

Curli

"Gram-negative bacteria assemble functional amyloid surface fibers called curli."[23] Curli are a type of fimbriae.[19] Curli are composed of proteins called curlins.[23] Some of the genes involved are CsgA, CsgB, CsgC, CsgD, CsgE, CsgF, and CsgG.[23]

Virulence

Pili are responsible for virulence in the pathogenic strains of many bacteria, including E. coli, Vibrio cholerae, and many strains of Streptococcus.[24][25] This is because the presence of pili greatly enhances bacteria's ability to bind to body tissues, which then increases replication rates and ability to interact with the host organism.[24] If a species of bacteria has multiple strains but only some are pathogenic, it is likely that the pathogenic strains will have pili while the nonpathogenic strains do not.[26][27]

The development of attachment pili may then result in the development of further virulence traits. Fimbriae are one of the primary mechanisms of virulence for E. coli, Bordetella pertussis, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus bacteria. Their presence greatly enhances the bacteria's ability to attach to the host and cause disease.[28] Nonpathogenic strains of V. cholerae first evolved pili, allowing them to bind to human tissues and form microcolonies.[24][27] These pili then served as binding sites for the lysogenic bacteriophage that carries the disease-causing toxin.[24][27] The gene for this toxin, once incorporated into the bacterium's genome, is expressed when the gene coding for the pilus is expressed (hence the name "toxin mediated pilus").[24]

See also

References

- "pilus" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

- Brinton, Charles (1954). "Electrophoresis and phage susceptibility studies on a filament-producing variant of the E. coli bacterium". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 15 (4): 533–542. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(54)90011-6. PMID 13230101.

- Chagnot, C; Zorgani, MA; Astruc, T; Desvaux, M (14 October 2013). "Proteinaceous determinants of surface colonization in bacteria: bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation from a protein secretion perspective". Frontiers in Microbiology. 4: 303. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2013.00303. PMC 3796261. PMID 24133488.

- "Gut bacteria use super-polymers to dodge antibiotics | Imperial News | Imperial College London". Imperial News.

- Patkowski, Jonasz B.; Dahlberg, Tobias; Amin, Himani; Gahlot, Dharmender K.; Vijayrajratnam, Sukhithasri; Vogel, Joseph P.; Francis, Matthew S.; Baker, Joseph L.; Andersson, Magnus; Costa, Tiago R. D. (5 April 2023). "The F-pilus biomechanical adaptability accelerates conjugative dissemination of antimicrobial resistance and biofilm formation". Nature Communications. 14 (1): 1879. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-37600-y. PMC 10076315. PMID 37019921.

- Beltran, Leticia C.; Cvirkaite-Krupovic, Virginija; Miller, Jessalyn; Wang, Fengbin; Kreutzberger, Mark A. B.; Patkowski, Jonasz B.; Costa, Tiago R. D.; Schouten, Stefan; Levental, Ilya; Conticello, Vincent P.; Egelman, Edward H.; Krupovic, Mart (2023-02-07). "Archaeal DNA-import apparatus is homologous to bacterial conjugation machinery". Nature Communications. 14 (1): 666. doi:10.1038/s41467-023-36349-8. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 9905601. PMID 36750723.

- van Wolferen, Marleen; Wagner, Alexander; van der Does, Chris; Albers, Sonja-Verena (2016-03-01). "The archaeal Ced system imports DNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (9): 2496–2501. Bibcode:2016PNAS..113.2496V. doi:10.1073/pnas.1513740113. ISSN 1091-6490. PMC 4780597. PMID 26884154.

- Proft, T.; Baker, E. N. (February 2009). "Pili in Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria — structure, assembly and their role in disease". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 66 (4): 613–635. doi:10.1007/s00018-008-8477-4. PMID 18953686. S2CID 860681.

- Ottow, JC (1975). "Ecology, physiology, and genetics of fimbriae and pili". Annual Review of Microbiology. 29: 79–108. doi:10.1146/annurev.mi.29.100175.000455. PMID 1180526.

- Filloux, A (July 2010). "A variety of bacterial pili involved in horizontal gene transfer". Journal of Bacteriology. 192 (13): 3243–5. doi:10.1128/JB.00424-10. PMC 2897649. PMID 20418394.

- Joan, Slonczewski (2017). Microbiology : an evolving science. Foster, John Watkins (Fourth ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 1000–1002. ISBN 9780393614039. OCLC 951925510.

- Mattick JS (2002). "Type IV pili and twitching motility". Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 56 (1): 289–314. doi:10.1146/annurev.micro.56.012302.160938. PMID 12142488.

- Jarrell; et al. (2009). "Archaeal Flagella and Pili". Pili and Flagella: Current Research and Future Trends. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-48-6.

- Wang, F; Cvirkaite-Krupovic, V; Kreutzberger, MAB; Su, Z; de Oliveira, GAP; Osinski, T; Sherman, N; DiMaio, F; Wall, JS; Prangishvili, D; Krupovic, M; Egelman, EH (2019). "An extensively glycosylated archaeal pilus survives extreme conditions". Nature Microbiology. 4 (8): 1401–1410. doi:10.1038/s41564-019-0458-x. PMC 6656605. PMID 31110358.

- Cehovin A, Simpson PJ, McDowell MA, Brown DR, Noschese R, Pallett M, Brady J, Baldwin GS, Lea SM, Matthews SJ, Pelicic V (2013). "Specific DNA recognition mediated by a type IV pilin". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 (8): 3065–70. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.3065C. doi:10.1073/pnas.1218832110. PMC 3581936. PMID 23386723.

- Davidsen T, Rødland EA, Lagesen K, Seeberg E, Rognes T, Tønjum T (2004). "Biased distribution of DNA uptake sequences towards genome maintenance genes". Nucleic Acids Res. 32 (3): 1050–8. doi:10.1093/nar/gkh255. PMC 373393. PMID 14960717.

- Caugant DA, Maiden MC (2009). "Meningococcal carriage and disease--population biology and evolution". Vaccine. 27 Suppl 2 (4): B64–70. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.04.061. PMC 2719693. PMID 19464092.

- Nuccio SP, et al. (2007). "Evolution of the chaperone/usher assembly pathway: fimbrial classification goes Greek". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 71 (4): 551–575. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00014-07. PMC 2168650. PMID 18063717.

- Cookson, AL; Cooley, WA; Woodward, MJ (2002), "The role of type 1 and curli fimbriae of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in adherence to abiotic surfaces", Int J Med Microbiol, 292 (3–4): 195–205, doi:10.1078/1438-4221-00203, PMID 12398210.

- Kolenda, Rafal; Ugorski, Maciej; Grzymajlo, Krzysztof (14 May 2019). "Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Salmonella Type 1 Fimbriae, but Were Afraid to Ask". Frontiers in Microbiology. 10: 1017. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2019.01017. PMC 6527747. PMID 31139165.

- Rice JC, Peng T, Spence JS, Wang HQ, Goldblum RM, Corthésy B, Nowicki BJ (December 2005). "Pyelonephritic Escherichia coli expressing P fimbriae decrease immune response of the mouse kidney". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 16 (12): 3583–91. doi:10.1681/ASN.2005030243. PMID 16236807.

- WI, Kenneth Todar, Madison. "Colonization and Invasion by Bacterial Pathogens". www.textbookofbacteriology.net. Retrieved 2016-12-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Epstein, EA; Reizian, MA; Chapman, MR (2009), "Spatial clustering of the curlin secretion lipoprotein requires curli fiber assembly.", J Bacteriol, 191 (2): 608–615, doi:10.1128/JB.01244-08, PMC 2620823, PMID 19011034.

- Craig, Lisa; Taylor, Ronald (2014). "Chapter 1: The Vibrio cholerae Toxin Coregulated Pilus: Structure, Assembly, and Function with Implications for Vaccine Design". In Barocchi, Michèle; Telford, John (eds.). Bacterial Pili: Structure, Synthesis, and Role in Disease. C.A.B. International. pp. 1–16. ISBN 978-1-78064-255-0.

- Rinaudo, Daniela; Moschioni, Monica (2014). "Chapter 13: Pilus-based Vaccine Development in Streptococci: Variability, Diversity, and Immunological Resposes". In Barocchi, Michèle; Telford, John (eds.). Bacterial Pili: Structure, Synthesis, and Role in Disease. C.A.B. International. pp. 182–202. ISBN 978-1-78064-255-0.

- Todar, Kenneth. "Textbook of Bacteriology: Bacterial Structure in Relationship to Pathogenicity". Textbook of Bacteriology. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- Georgiadou, Michaella; Pelicic, Vladimir (2014). "Chapter 5: Type IV Pili: Functions & Biogenesis". In Barocchi, Michèle; Telford, John (eds.). Bacterial Pili: Structure, Synthesis, and Role in Disease. C.A.B. International. pp. 71–84. ISBN 978-1-78064-255-0.

- Connell I, Agace W, Klemm P, Schembri M, Mărild S, Svanborg C (September 1996). "Type 1 fimbrial expression enhances Escherichia coli virulence for the urinary tract". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93 (18): 9827–32. Bibcode:1996PNAS...93.9827C. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.18.9827. PMC 38514. PMID 8790416.

External links

- Sex+Pilus at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Bacterial+Pilus at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Fimbriae+Proteins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)