Camp Conlie

Camp Conlie was one of eleven military camps established by the Republican Government of National Defense under Léon Gambetta during the Franco-Prussian war. It became notable because of events which have led to its being described as a "concentration camp", in which troops from Brittany were supposedly incarcerated and persecuted.[1] This became a significant atrocity story within Breton nationalism.

Background

After the defeat of French forces at the Battle of Sedan, and the fall of the monarchy of Napoleon III, a new republic was proclaimed. The new government decided to form a new army and continue the war. Major General Émile de Kératry was made responsible for establishing a camp at Conlie in the region of Le Mans and mobilized volunteers from the west of France to form an "army of Brittany". The mobilized quota from the five departments of Brittany was 80,000 men. It was intended that these troops would be equipped with the weapons left over from the American Civil War, but these promised weapons failed to materialize.

Because of a history of anti-republicanism in Brittany, Gambetta doubted the reliability of these troops, and Kératry was suspected of separatist inclinations.

The huts were not built when the soldiers arrived. In consequence, they were housed in emergency tents. Bad weather and the recently ploughed land quickly created a quagmire in which it was difficult to move. A lack of instructors, equipment and supplies caused frustration. Disease caused significant mortality.

Rumours

Rumours about the camp began to circulate in Brittany. As visiting English journalist Ernest Vizetelly noted,

The most appalling rumours were current throughout Brittany regarding the new camp. It was said to be grossly mismanaged and a hotbed of disease. I visited it and prepared an article which was printed by the Daily News ...So far as the camp's defences and the arming of the men within it were concerned my strictures were fully justified.[2]

Nevertheless, Vizetelly argued that poor conditions, though real, were explicable,

The critics of the camp have said that the spot was very damp and muddy, and therefore necessarily unhealthy, and there is truth in that assertion; but the same might be remarked of all the camps of the period, notably that of D'Aurelle de Paladines in front of Orleans. Moreover, when a week's snow was followed by a fortnight's thaw, matters could scarcely be different. From first to last (November 12 to January 7) 1942 cases of illness were treated in the five ambulances of the camp. Among them were 264 cases of small-pox. There were a great many instances of bronchitis and kindred affections, but not many of dysentery. Among the small-pox cases 88 proved fatal. I find on referring to documents of the period that on November 23, the day before Gambetta visited the camp, as I shall presently relate, the total effective was 665 officers with 23,881 men. By December 5 (although a marching division of about 12,000 men had then left for the front) the effective had risen to 1241 officers with about 40,000 men. There were 40 guns for the defence of the camp, and some 50 field-pieces of various types, often, however, without carriages and almost invariably without teams. At no time, I find, were there more than 360 horses and fifty mules in the camp. There was also a great scarcity of ammunition for the guns.[2]

Battles

Gambetta decided to send 12,000 men from camp Conlie, armed with only 4000 badly maintained rifles, against the forces of the Duke of Mecklenburg. Given the repeated refusal of the Government to properly arm his men, Kératry resigned in protest on November 27, leaving the command to his deputy, General Le Bouëdec. General Marivault, who succeeded him, called, from December 10, for the partial evacuation of the camp, because of the poor conditions. This was denied by Gambetta, who visited the camp, declaring the situation to be excellent. The General Staff were evacuated. Gambetta eventually agreed to evacuate the camp at the end of December, at the insistence of General Freycinet.

The remaining 19,000 troops were incorporated into the 2nd Army of the Loire, and the camp was closed on January 7, 1871. On the eve of the Battle of Le Mans (10 and 11 January 1871), these 19,000 troops were sent to the front line, bearing poor quality arms. The French army, led by Antoine Chanzy, was crushed by the Prussians. Chanzy blamed the Breton troops.

The Prussians reached Camp Conlie on January 14. French defenders blew up the fortifications and retreated from the town on March 6.

Effects

From November 1870 to January 1871 there were 143 deaths from disease including 88 of smallpox. 2000 of the soldiers had to be sent to the infirmary. The report of a commission of inquiry prepared by Breton historian Arthur de La Borderie was overwhelmingly critical of the French army, which demonstrated a total lack of organization.

The Camp Conlie affair raised general indignation in Brittany. The camp was not a "concentration camp" (the term was invented some twenty years later and the supposed "detainees" were volunteers under military instruction, even if they were neither equipped, trained, or armed), but it is perceived as such in the collective unconscious of many Breton nationalists. A monument was inaugurated on May 11, 1913 on the hill of the Jaunelière. A commemorative plaque was affixed on February 14, 1971 during the centennial.

Earliest picture postcard

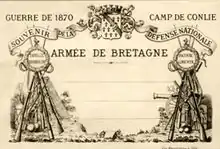

In 1904 it was claimed that the world's first picture postcard had been created at Camp Conlie. After publicity following the death of the German entrepreneur who claimed have invented them, Léon Besnardeau (1829–1914) announced that the first cards had been created by him for soldiers in the camp to communicate with relatives. They had a lithographed design printed on them containing emblematic images of piles of armaments on either side of a scroll topped by the arms of the Duchy of Brittany and the inscription "War of 1870. Conlie camp. Souvenir of the National Defence. Brittany Army".[3] While these are certainly the first known picture postcards, there was no space for stamps and no evidence that they were ever posted without envelopes.[4]

References

- The term is used by Breton nationalist author Yann Brekilien in L'holocauste breton, Editions du Rocher, 1994, ISBN 2-268-01709-5

- Ernest Alfred Vizetelly, My Days of Adventure, BiblioBazaar, 2007, p. 180-2

- The New York Times, September 21, 1904.

- http://www.cartolis.org/histoire.php Archived 2011-07-18 at the Wayback Machine Histoire de la Carte Postale, Cartopole, Baud.

Bibliography

- Yann Brekilien, L'holocauste breton, Editions du Rocher, 1994, ISBN 2-268-01709-5,

- Philippe Le Moing-Kerrand, Les bretons dans la guerre de 1870, 1999,

- Hervé Martin, Louis Martin, Le Finistère face à la modernité entre 1850 et 1900, 2004, Apogée, ISBN 2-84398-163-8

- Jean Sibenaler, "Conlie, Les soldats oubliés de l'armée de Bretagne", éditions Cheminements, 2007