Consolidated Mines

Consolidated Mines, also known as Great Consolidated mine, but most commonly called Consols or Great Consols was a metalliferous mine about a mile ESE of the village of St Day, Cornwall, England. Mainly active during the first half of the 19th century, its mining sett was about 600 yards north–south; and 2,700 yards east–west, to the east of Carharrack. Although always much troubled by underground water, the mine was at times highly profitable, and it was the largest single producer of copper ore in Cornwall. Today the mine is part of the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Site.

The Wheal Maid area of the mine | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

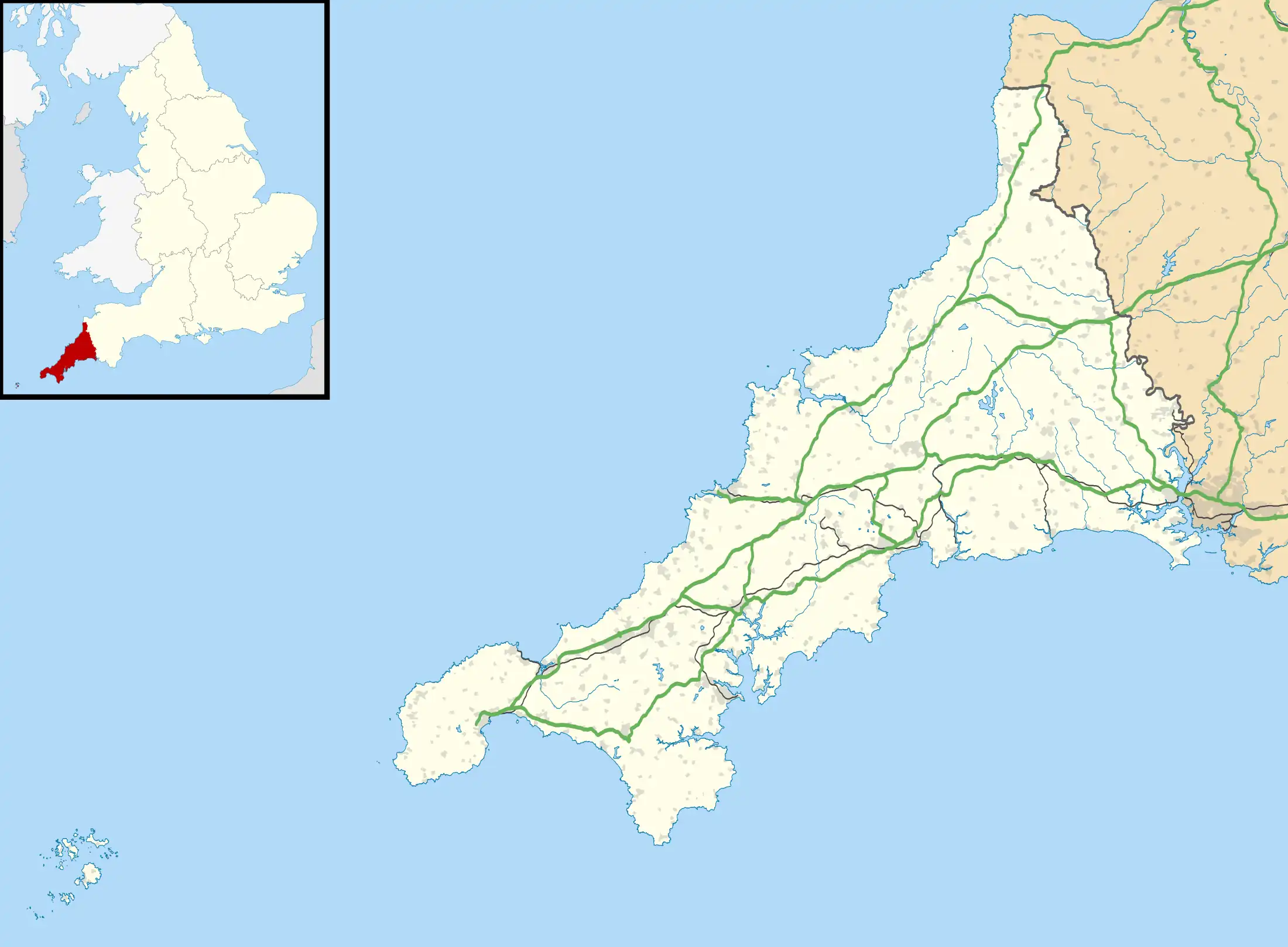

Consolidated Mines Location in Cornwall | |

| Location | Gwennap |

| County | Cornwall |

| Country | England |

| Coordinates | 50°14′06″N 5°09′47″W |

| Production | |

| Products | Primarily copper |

| History | |

| Opened | 1782 |

| Closed | 1857 (merged with United Downs in 1861) |

Geology

The country rock at the mine was killas and the mine's main produce was copper, though small amounts of black tin, arsenic, pyrite and zinc ore were also raised.[1] There are about eight main lodes at the mine, crossed by elvan dykes. The most important lode was Virgin Lode which was stoped for over 1.3 miles (2.1 km).[2]

History to 1800

Although there had been mining in the area for over 400 years,[3] Consolidated Mines was formed in 1782 by the amalgamation of a number of neighbouring mines including Wheal Girl, West Wheal Virgin, Wheal Virgin, Wheal Maid, Wheal Fortune and Carharrack mine.[2][4] The underground workings of these mines were interconnected, and before the merger they had been having significant problems with underground water. They were jointly running seven Newcomen engines to pump water from their workings into the Great County Adit,[5] but the engines had been struggling to keep the water levels down and they were so expensive to run that all the mines had closed during 1779.[6]

As part of the merger, five Boulton and Watt engines were ordered to replace the seven Newcomens. The new engines were operational by 1782 and saved almost £11,000 a year on coal, though the mine had to agree to Boulton and Watt's standard terms which included payment of an annual charge (known as "dues") of one third of the fuel saved. In fact the mine negotiated with the company and paid £2,500 each year.[4][6] In 1784, Boulton and Watt built the first steam whim (winding engine) in Cornwall here,[7] and in 1788 they installed an underground pumping engine on the Wheal Virgin site; this was one of only two underground engines installed in Cornwall before 1850.[8]

The end of the 18th century was a difficult time for Cornish copper mines, because the vast quantity of ore that was being mined cheaply from Parys Mountain in Anglesey was flooding the market. In 1787 Consols made a loss of some £8,000,[9] and some time in the 1780s Boulton and Watt acquired an interest in the mine, probably in lieu of payment of their dues; furthermore in around 1788 the company reduced the dues to £1,000 a year to help keep the mine open.[10] At this time it was one of only two mines in Cornwall to employ over a thousand people, North Downs mine being the other.[11]

1800 onwards

The Parys Mountain ore was mined out by about 1800, and the price of copper soon rose again, reaching a high of £138 per ton in 1805. Many new mines were started and existing mines restarted at this time.[12] Despite this boom, for some unknown reason Consols was substantially closed in or just before 1811 and it was not until 1819 that mining entrepreneur John Taylor raised the capital (around £65,000) to restart the mine.[13] The mine rapidly became profitable, but its problem with underground water continued, and in 1820 "Job's Engine", which had a 90-inch-diameter cylinder, was installed for pumping water, followed in the next year by another engine of the same size. Both were single-cylinder engines designed by Arthur Woolf and built by the Neath Abbey Ironworks, and they were celebrated as being the largest and most powerful steam engines in the world at the time.[14] A 58-inch engine was also installed, and by 1829 another three engines had to be added.[15]

In 1824 Taylor built the Redruth and Chasewater Railway to transport the ore from this mine (and other ones nearby) to the port of Devoran.[7] By 1839 the mine was employing 3,000 people,[7] and the previous year it was recorded that 826 men and boys were working more than 100 fathoms (180 m) underground, at an average depth of 229 fathoms (419 m).[16] One of the youngest children recorded as working down a Cornish mine was killed near the 120 fathoms (220 m) level in November 1831. He was eight years old.[17] Some of the lower workings were extremely hot: for instance the air temperature at the 294 fathom (538 m) level was recorded at 96 °F (36 °C), increasing to 108 °F (42 °C) in places, and the water that collected at the bottom of Davey's shaft was 92.5 °F (33.6 °C)—the men working in the lower levels used this to cool themselves![18]

During its relatively short life, Consols was a phenomenally productive copper mine: between 1819 and 1858 it produced 442,493 tons of ore, the largest quantity from any single mine in Cornwall,[19] and the ore it had sold had realised over £2 million.[20] Such was its fame that many other mines were opened using the words "Consolidated" or "Consols" in their names, hoping to profit by association with the success story.[21]

By the 1850s it was clear that the copper mines in the west of Cornwall were becoming exhausted and this together with the start of foreign production (from Chile, for instance) led to a spate of closures or further mergers to reduce running costs. Consolidated Mines ceased working in 1857,[22] and in 1861 amalgamated with the neighbouring United Mines and Wheal Clifford to form Clifford Amalgamated Mines, which continued, unprofitably, until 1870.[23]

Today

Today, the site is within area A6i (The Gwennap Mining District) of the Cornwall and West Devon Mining Landscape World Heritage Site.[24] Several of the shafts at the mine are still open, but covered with "Clwyd Caps", which are pyramidal wire meshes. These include Bawden's shaft, Michell's shaft, and Woolf's shaft which was sunk in 1826 and at 300 fathoms was one of the deepest in the area. There are a few ruined buildings, a tall chimney and two engine houses in ruins.[3] A clock tower survives at the former site of Wheal Maid.[7]

References

- Dines 1956, p.420

- Dines 1956, p.418

- "Consolidated Mines (Consols)". Cornwall in Focus. Archived from the original on 28 January 2010. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- Barton 1978, p.31

- Buckley 2000, p.49

- Hamilton Jenkin 1972, p.101

- Hancock 2008, pp. 65–66

- Barton 1966, p.233

- Hamilton Jenkin 1972, p.158

- Barton 1978, pp.32,37

- Hamilton Jenkin 1972, p.91

- Barton 1978, p.45

- Barton 1978, p.51

- Barton 1966, p.41

- Barton 1978, p.52

- Barton 1966, p.207

- Barton 1968, p.14 (footnote)

- Hamilton Jenkin 1972, p.219

- Barton 1978 p.95

- Barton 1978 p.71

- Barton 1968, p.102

- Barton 1978 p.79

- Barton 1978 p.89

- "Cornish Mining World Heritage - Gwennap Mining District Location Map". Cornwall Council. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

Sources

- Barton, D. B. (1966). The Cornish Beam Engine (New ed.). Truro: D. Bradford Barton Ltd.

- Barton, D. B. (1968). Essays in Cornish Mining History, Volume 1. Truro: D. Bradford Barton.

- Barton, D. B. (1978). A History of Copper Mining in Cornwall and Devon (3rd ed.). Truro: D. Bradford Barton Ltd.

- Buckley, J A (2000). The Great County Adit. Pool, Camborne, Cornwall: Penhellick Publications. ISBN 1-871678-51-X.

- Dines, H. G. (1956). The Metalliferous Mining Region of South-West England. Volume I. London: HMSO. pp. 418–420.

- Hamilton Jenkin, A. K. (1972). The Cornish Miner (4th ed.). Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-5486-8.

- Hancock, Peter (2008). The Mining Heritage of Cornwall and West Devon. Wellington, Somerset: Halsgrove. ISBN 978-1-84114-753-6.