Constantine II of Greece

Constantine II (Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Βʹ, romanized: Konstantínos II, pronounced [ˌkonstaˈdinos ðefˈteros]; 2 June 1940 – 10 January 2023)[2] was the last king of Greece, reigning from 6 March 1964 until the abolition of the Greek monarchy on 1 June 1973.

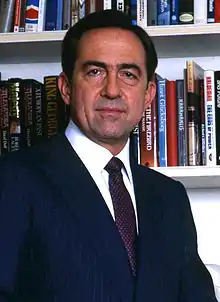

| Constantine II | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrait by Allan Warren, 1987 | |||||||||||||||

| King of the Hellenes | |||||||||||||||

| Reign | 6 March 1964 – 1 June 1973 | ||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Paul | ||||||||||||||

| Successor | Monarchy abolished; | ||||||||||||||

| Prime ministers | |||||||||||||||

| Regent of Greece | |||||||||||||||

| Tenure | 20 February 1964 – 6 March 1964[1] | ||||||||||||||

| Monarch | Paul | ||||||||||||||

| Head of the Royal House of Greece | |||||||||||||||

| Tenure | 6 March 1964 – 10 January 2023 | ||||||||||||||

| Successor | Pavlos | ||||||||||||||

| Born | 2 June 1940 Athens, Greece | ||||||||||||||

| Died | 10 January 2023 (aged 82) Athens, Greece | ||||||||||||||

| Burial | 16 January 2023 Royal Cemetery, Tatoi Palace, Greece | ||||||||||||||

| Spouse | |||||||||||||||

| Issue | |||||||||||||||

| House | Glücksburg | ||||||||||||||

| Father | Paul of Greece | ||||||||||||||

| Mother | Frederica of Hanover | ||||||||||||||

| Religion | Greek Orthodox | ||||||||||||||

| Military career | |||||||||||||||

| Allegiance | Kingdom of Greece | ||||||||||||||

| Service/ | |||||||||||||||

| Rank | |||||||||||||||

| Sports career | |||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||

Constantine was born in Athens as the only son of Crown Prince Paul and Crown Princess Frederica of Greece. Being of Danish descent, he was also born as a prince of Denmark. As his family was forced into exile during the Second World War, he spent the first years of his childhood in Egypt and South Africa. He returned to Greece with his family in 1946 during the Greek Civil War. After Constantine's uncle George II died in 1947, Paul became the new king and Constantine the crown prince. As a young man, Constantine was a competitive sailor and Olympian, winning a gold medal in the 1960 Rome Olympics in the Dragon class along with Odysseus Eskitzoglou and George Zaimis in the yacht Nireus. From 1964, he served on the International Olympic Committee.

Constantine acceded as king following his father's death in 1964. Later that year, he married Princess Anne-Marie of Denmark, with whom he had five children. Although the accession of the young monarch was initially regarded auspiciously, his reign saw political instability that culminated in the Colonels' Coup of 21 April 1967. The coup left Constantine, as head of state, with little room to manoeuvre since he had no loyal military forces on which to rely. He thus reluctantly agreed to inaugurate the junta, on the condition that it be made up largely of civilian ministers. On 13 December 1967, Constantine was forced to flee the country, following an unsuccessful countercoup against the junta.

Constantine formally remained Greece's head of state in exile until the junta abolished the monarchy in June 1973 (a decision ratified via a referendum in July). After the restoration of democracy a year later, a second referendum was held in December 1974, which confirmed the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of the Third Hellenic Republic. While Constantine had contested the results of the 1973 referendum, he accepted the verdict of the 1974 vote, even though he had not been allowed to return to Greece to campaign.[3][4] After living for several decades in London, Constantine moved back to Athens in 2013. He died there in 2023 following a stroke.

Early life

Constantine was born in the afternoon of 2 June 1940 at his parents' residence, Villa Psychiko at Leoforos Diamantidou 14 in Psychiko, an affluent suburb of Athens.[5] He was the second child and only son of Crown Prince Paul and Crown Princess Frederica. His father was the younger brother and heir presumptive of the reigning Greek king, George II, and his mother was the only daughter of Ernest Augustus, Duke of Brunswick, and Princess Victoria Louise of Prussia.[6][7]

Prince Constantine had an elder sister, Princess Sofia, born in 1938.[6] However, since agnatic primogeniture governed the succession to throne in Greece at the time, the birth of a male heir to the throne had been anxiously awaited by the Greek royal family, and the newborn prince was therefore received with joy by his parents.[8][9] His birth was celebrated with a 101–gun salute from Mount Lycabettus in Athens, which, according to tradition, announced that the newborn was a boy.[10] According to Greek naming practices, being the first son, he was named after his paternal grandfather, Constantine I, who had died 17 years earlier in 1923.[11] At his baptism on 20 July 1940 at the Royal Palace of Athens, the Hellenic Armed Forces acted as his godparent.[12][13]

World War II and the exile of the royal family

Constantine was born during the early stages of World War II. He was just a few months old when, on 28 October 1940, Fascist Italy invaded Greece from Albania, beginning the Greco-Italian War. The Greek Army was able to halt the invasion temporarily and push the Italians back into Albania.[14][15][16] However, the Greek successes forced Nazi Germany to intervene and the Germans invaded Greece and Yugoslavia on 6 April 1941 and overran both countries within a month, despite British aid to Greece in the form of an expeditionary corps.[17][18] On 22 April 1941, Princess Frederica and her two children, Sofia and Constantine, were evacuated to Crete in a British Short Sunderland flying boat along with most of the Greek royal family. The next day, they were followed by King George and Prince Paul. However the imminent German invasion of Crete quickly made the situation untenable and Constantine and his family were evacuated from Crete to Egypt on 30 April 1941, a fortnight before the German attack on the island.[19] In Alexandria, the exiled Greek royals were welcomed by the Greek diaspora, which provided them with lodging, money and clothing.[20] The presence of the Greek royal family and government began to worry King Farouk I of Egypt and his pro-Italian ministers. Constantine and his family, therefore, had to seek another refuge where they could get through the war and continue their fight against the Axis powers. George VI of the United Kingdom opposed the presence of Princess Frederica, who was suspected of having Nazi sympathies[21] and her children in Britain, but it was decided that Constantine's father and uncle could take up residence in London, where a government-in-exile was set up, while the rest of the family could seek refuge in the then-Union of South Africa.[22][23]

On 27 June 1941, most of the Greek royal family, therefore, set off for South Africa on board the Dutch steamship Nieuw Amsterdam, which arrived in Durban on 8 July 1941.[20][24][25] After a two-month stay in Durban, Prince Paul left for England with his brother, and Constantine then barely saw his father again for the next three years.[26] [27] The rest of the family settled in Cape Town, where the family was joined by a younger sister, Princess Irene, born in 1942.[6] Prince Constantine, Princess Sofia, their mother and their aunt Princess Katherine were initially lodged with South African Governor-General Patrick Duncan at his official residence Westbrooke in Cape Town.[28][29]

The group subsequently moved several times until they settled in Villa Irene in Pretoria with Prime Minister Jan Smuts, who quickly became a close friend of the exiled Greeks.[28][30][31] From early 1944, the family again took up residence in Egypt. In January 1944, Princess Frederica was reunited with her husband in Cairo, and their children joined them in March of that year. Despite their difficult financial circumstances, the family then established friendly relations with several Egyptian personalities, including Queen Farida, whose daughters were roughly the same age as Constantine and his sisters.[32]

After World War II and return to Greece

In 1944, at the end of World War II, Nazi Germany gradually withdrew from Greece. While the majority of exiled Greeks were able to return to their country, the royal family had to remain in exile because of the growing republican opposition at home. Britain tried to reinstate King George, who remained in exile in London, but most of the resistance, in particular the communists, were opposed. Instead, George had to appoint from exile a Regency Council headed by Archbishop Damaskinos of Athens, who immediately appointed a republican-majority government headed by Nikolaos Plastiras.[33][34][35] George, who was humiliated, ill and powerless, considered abdicating for a time in favour of his brother, but eventually decided against it.[33][34][35]

Prince Paul, who was more combative but also more popular than his brother, would have liked to return to Greece as heir to the throne as early as the liberation of Athens in 1944, as he believed that back in his country he would have been quickly proclaimed regent, which would have blocked the way for Damaskinos and made it easier to restore the monarchy.[36]

However, the unstable situation in the country and the polarisation between communists and bourgeois allowed the monarchists to return to power after the parliamentary elections of March 1946. After becoming prime minister, Konstantinos Tsaldaris organised a referendum on 1 September 1946 with the aim of allowing George to return to the throne. The majority in the referendum was in favour of reinstating the monarchy, at which time Constantine and his family also returned to Greece. In a country still suffering from rationing and deprivation, they moved back to the villa in Psychikó. It was there that Prince Paul and Princess Frederica chose to start a small school, where Constantine and his sisters received their first education[37] under the supervision of Jocelin Winthrop Young, a British disciple of the German-Jewish educator Kurt Hahn.[38][39][40]

The tension between communists and conservatives led, in the following years, to the Greek Civil War. That conflict was fought mainly in northern Greece. The Civil War ended in 1949, with the victory of the bourgeois and royalists, who had been supported by Britain and the United States.[41]

Crown Prince

Education

During the Civil War, on 1 April 1947, George died. Thus, Constantine's father ascended the throne, and Constantine himself became Crown Prince of Greece at the age of six.[42][43] He then moved with his family from the villa in Psychiko to Tatoi Palace at the foot of the Parnitha Mountains in the northern part of the Attica peninsula.[44]

The first years of Paul's reign did not bring great upheavals in his son's daily life. Constantine and his sisters were brought up relatively simply, and communication was at the heart of the pedagogy of their parents, who spent all the time they could with their children.[45][46] Supervised by various British governesses and tutors, the children spoke English in the family but were also fluent in Greek.[47] Until he was nine, Constantine continued to be educated with his sisters and other companions from Athens' wealthier population in the villa at Psychiko.[38]

After that age, Paul decided to begin preparing his son for the throne. He then started at the Anávryta lyceum in Marousi, northeast of Athens, which also followed Kurt Hahn's pedagogy. He attended school there as a boarder between 1950 and 1958,[48] while his sisters attended school in Salem, Baden-Württemberg, Germany.[38][49][50] From 1955, Constantine served in all three branches of the Hellenic Armed Forces, attending the requisite military academies. He also attended the NATO Air Force Special Weapons School in Germany, as well as the University of Athens, where he took courses in the school of law.[7] In 1955, he received the title of Duke of Sparta.[51]

Sailing and the Olympic Games

Constantine was an able sportsman. In 1958, Paul gave his son a Lightning class sailing boat for Christmas. Subsequently, Constantine spent most of his free time training with the boat on the Saronic Gulf. After a few months, the Greek Navy gave the prince a Dragon class sailing boat, with which he decided to participate in the 1960 Summer Olympics in Rome.[52] At the opening of the Games in Rome, he was the flag bearer for the Greek team.[53] He won an Olympic gold medal in Sailing (Dragon class), which was the first Greek gold medal in sailing since the Stockholm 1912 Summer Olympics.[54] Constantine was the helmsman of the boat Nireus and other members of the team included Odysseus Eskitzoglou and Georgios Zaimis.[53]

Constantine was also a strong swimmer and had a black belt in karate, with interests in squash, track events, and riding.[7] In 1963, Constantine became a member of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). He resigned in 1974 because he was no longer a Greek resident, and was made an honorary IOC member.[55] He was an honorary member of the International Soling Association[56] and president of the International Dragon Association.[57]

Reign

Accession

In 1964, Paul's health deteriorated rapidly. He was diagnosed with stomach cancer and underwent surgery for an ulcer in February. Prior to this, Constantine had already been appointed regent for his ailing father while waiting for his recovery.[58] During his regency, Constantine limited himself to signing decrees and appointing members of the government, as well as accepting their resignations.[51] As the king's condition worsened, the crown prince went to Tinos to attain an icon considered miraculous by the Greek Orthodox Church. On 6 March 1964, Paul died and the 23-year-old Constantine succeeded him as King of the Hellenes.[59][60][61] The new king ascended the throne as Constantine II, although some of his supporters preferred to call him Constantine XIII to emphasise the continuity between the former Byzantine Empire and the Kingdom of Greece.[62] On 23 March 1964, he was sworn in before the parliament and was invested as chief of the armed forces with the highest ranks in each branch.[53][63]

Due to his youth, Constantine was also perceived as a promise of change. Greece was still feeling the effects of the Civil War and society was strongly polarised between the royalist-conservative right wing and the liberal-socialist left wing. The accession of Constantine coincided with the recent election of centrist George Papandreou as prime minister in February 1964, which ended 11 years of right-wing rule by the National Radical Union (ERE). The Greek society hoped that the new young king and the new prime minister would be able to overcome past dissensions.[62][64]

Apostasia of 1965

Constantine succeeded to the throne at a time when Greek society was experiencing economic and employment growth, but also political crises and violent social protests.[65] Political instability worsened in 1965. At a meeting with Papandreou that took place on 11 July 1965 in Korfu, Constantine requested that those implicated in the ASPIDA scandal, in which several military officials tried to prevent attempts by the extreme right-wing military to seize power, be referred to a military tribunal.[53][66] Papandreou agreed and raised with him his intention to dismiss the then minister of defence, Petros Garoufalias, so that he could take charge himself of the ministry.[53] Constantine refused, as the scandal wrongly implicated the prime minister's son, Andreas Papandreou.[53] After several clashes by letter between the monarch and the prime minister, Papandreou resigned on 15 July.[67][68] Following the resignation, at least 39 members of Parliament left Center Union.[65]

Constantine appointed a new government led by Georgios Athanasiadis-Novas, speaker of the parliament, which was formed by defectors disaffected with the Papandreous (the 'Apostates').[67][68] Soon, thousands of citizens took to the streets to protest against Constantine's decision, unprecedented protests that led to clashes with the Cities Police.[65][67] On 21 July 1965, the protests in the centre of Athens came to a head, and in one of these clashes a policeman killed the 25-year-old student Sotiris Petroulas, leader of the student movement and of the "Lambrakis Youth". His death became a symbol of the protests and his funeral was widely attended.[68][65] Athanasiadis-Novas's government did not receive a vote of confidence from parliament and Athanasiadis-Novas resigned on 5 August 1965. The two big parties, National Radical Union and Center Union, asked Constantine to call elections, but he asked Stefanos Stefanopoulos to form a government. He then ordered Ilias Tsirimokos to form a government on 18 August but he did not receive the vote of confidence of the parliament on a vote on 28 August either. Constantine finally ordered Stefanopoulos to form a government and obtained the parliamentary confidence on 17 December 1965. An end to the crisis seemed in sight when on 20 December 1966, Papandreou, ERE leader Panagiotis Kanellopoulos and the king reached a resolution; elections would be held under a straightforward system of proportional representation where all parties participating agreed to compete, and that, in any outcome, the command structure of the army would not be altered.[69] The third "apostate" government fell on 22 December 1966, and was succeeded by Ioannis Paraskevopoulos, who was to govern until the parliamentary elections of 28 May 1967, which were expected to favour a victory for Georgios Papandreou's Centre Union.[70][71] Paraskevopoulos resigned and Kanellopoulos stepped in to fill the role of the Prime Minister on 3 April 1967 until the election.[72]

Greek dictatorship of 1967–1974

.jpg.webp)

Historians have suspected that Constantine and his mother were interested in a coup d'état from mid-1965 at the latest. US Army Attaché Charles Perkins reported that military right-wing group "Sacred Bond of Greek Officers" (IDEA) "plans for coup and military dictatorship in Greece", that Constantine was aware and that the group was aware that any operation in this direction with the cooperation of the US must have the permission of the king.[73] According to Charilaos Lagoudakis, a US State Department expert on Greece, by mid-1966 Constantine had already approved a coup plan.[73] On the other hand, historian C.M. Woodhouse rejects any involvement of Constantine in the conspiracy.[73]

A traditionalist, right-wing nationalist group of middle-ranking army officers led by Colonel George Papadopoulos took action first and staged a coup d'état on 21 April using the fear of "communist danger" as the main reason for coup.[71] Tanks rolled through the streets of Athens, a few rifle shots were heard and military songs were played on the radio until the announcement that "The Hellenic Armed Forces have undertaken the governance of the country" was made public. Some high-ranking politicians were arrested, as well as the commander-in-chief of the army.[74] The coup leaders met Constantine at his residence in Tatoi at about 7 a.m, which was surrounded by tanks to prevent resistance and the coup seemed to have succeeded bloodlessly. Constantine later recounted that the officers of the tank platoons believed they were carrying out the coup under his orders.[75] They asked Constantine to swear in the new government. Despite the urging of the detained Prime Minister Knellopoulos that the king resisted the coup, Constantine compromised with them to avoid bloodshed and in the afternoon swore in the new military government with Supreme Court prosecutor Konstantinos Kollias as prime minister.[71] On 26 April, in his speech on the new regime, he affirmed that "I am sure that with the will of God, with your efforts and above all with the help of the people, the organization of a State of Law, an authentic and healthy democracy".[68] According to the then-US ambassador to Greece, Phillips Talbot, Constantine expressed his anger at this situation, revealed to him that he no longer had control of the army and claimed that "incredibly stupid extreme right-wing bastards with control of the tanks are leading Greece to destruction".[76]

From his inauguration as king, Constantine already manifested his disagreements with Archbishop Chrysostomos II of Athens. With the military dictatorship, he had the opportunity to be removed from the Greek Orthodox Cephaly, in fact it was one of the first measures with which Constantine collaborated with the Junta. On 28 April 1967, Chrysostomos II was retained and was forced to resign after having to sign one of the two versions of the letter brought to him by an official of the royal palace. Finally, Ieronymos Kotsonis was elected as metropolitan by the junta's and Constantine's proposal on 13 May 1967.[77]

Royal countercoup of 13 December 1967 and exile

From the outset, the relationship between Constantine and the regime of the colonels was an uneasy one, especially when he refused to sign the decree imposing martial law and asked Talbot to flee Greece in an American helicopter with his family.[78][76] But the administration of US president Lyndon B. Johnson wanted to keep Constantine in Greece to negotiate with the junta for the return of democracy.[76] The presence of the United States Sixth Fleet in the Aegean Sea outraged the junta government, which forced Constantine to get rid of his private secretary, Michail Arnaoutis.[76] Arnaoutis, who had served as the king's military instructor in the 1950s and became his close friend, was generally reviled among the public for his role in the palace intrigues of the previous years. The junta, considering him an able and dangerous plotter, dismissed him from the army.[79] The king and his entourage were beginning to worry that the future of the monarchy was endangered.[76] Constantine visited the United States in the following days and in a meeting with Johnson, Constantine asked for military aid for a countercoup he was planning, but without success.[76] The junta, however, had information about Constantine's conspiracy.[76] Constantine later described himself as having the idea of a countercoup ten minutes after he found out about the junta's rise to power.[80]

Constantine began negotiations with the officials loyal to him in the summer of 1967. His objective was to mobilise the units of the army loyal to him and to restore parliamentary legitimacy. The action was planned by Lieutenant General Konstantinos Dovas.[76] Several military authorities joined the plan, including lieutenant general Antonakos, chief of the air force, Konstantinos Kollias, lieutenant general Kechagias, Ioannis Manettas, brigadier generals Erselman and Vidalis, major general Zalochoris, and others, so it was expected that the counterattack would be successful.[76] The king communicated with Konstantinos Karamanlis, who was exiled in Paris and aware of the plot, and attempted to persuade him return to assume the post of prime minister if this movement was successful, but he refused.[76] The main objective of the plan drawn up by the movement was that all the units initiated would occupy Thessaloniki and the king would send a message to the public.[76] It would follow the military operations in Tempi, Larissa and Lamia by the army and the swearing in of a new government by Archbishop Ieronymos with the participation of the centrist Georgios Mavros.[76] Constantine and the involved officials began to realise that the plan could fail as they didn't count on the active support of American intelligence, who were aware of the details of the plan.[76] They intended to initiate their plan on the day of a military parade scheduled for 28 October, but the junta-installed Chief of the Hellenic Army General Staff, Odysseas Angelis, refused to mobilise the units that Georgios Peridis requested. The abortive attempt, along with the visit of Constantine together with Peridis to some military divisions, were noted by the junta.[76]

On the morning of the day the countercoup had been rescheduled to, 13 December 1967, after eight months of planning the countercoup,[80] the royal family flew to Kavala, east of Thessaloniki, accompanied by Prime Minister Konstantinos Kollias who was informed at that moment of Constantine's plan. They arrived at 11:30 a.m. and were well received by the citizens.[76] But some conspirators were neutralised, such as General Manettas, and Odysseas Angelis informed the public of the plan, asking citizens to obey his orders minutes before telecommunications were cut off.[76] By noon, all the airbases, except one in Athens, had joined the royalist movement, and fleet leader Vice Admiral Dedes, before being arrested, ordered successfully the whole fleet sail towards Kavala in obedience to the king.[76] They did not manage to take Thessaloniki and it soon became apparent that the senior officers were not in control of their units. This, along with the arrest of several officers, including the capture of Peridis that afternoon, and the delay in the execution of some orders, led to the countercoup's failure.[76]

The junta, led by Georgios Papadopoulos, on the same day appointed General Georgios Zoitakis as Regent of Greece. Archbishop Ieronymos swore Zoitakis into office in Athens.[76] Constantine, the royal family and Prime Minister Konstantinos Kollias took off in torrential rain from Kavala for exile in Rome, where they arrived at 4 p.m. on 14 December, with their plane having only five minutes of fuel left.[80] In 2004, Constantine said that he would have done everything the same, but with more caution. Two weeks after his exile, photos of Constantine and his family celebrating Christmas with normality in the Greek Ambassador to Italy's home reached Greek media, which didn't do Constantine's reputation "any favour".[80] He remained in exile in Italy through the rest of military rule, although he technically continued as king until 1 June 1973. He was never to return to Greece as a reigning monarch.[76]

Constantine stated, "I am sure I shall go back the way my ancestors did."[78] He said to the Toronto Star:

I consider myself King of the Hellenes and sole expression of legality in my country until the Greek people freely decide otherwise. I fully expected that the (military) regime would depose me eventually. They are frightened of the Crown because it is a unifying force among the people.[7]

Throughout the dictatorship, Constantine maintained contact with the junta, maintaining direct communication with the colonels and kept the royal subsidy until 1973.[68] On 21 March 1972, Papadopoulos became Regent.[81] At the end of May 1973, senior officers of the Greek navy organised an abortive coup to overthrow the junta government, but failed.[68][63] The dictators considered Constantine to be involved, so on 1 June, with a constitutional act, Papadopoulos declared the monarchy abolished. He converted the country into a presidential and parliamentary state and assumed the interim presidency of the republic.[68][63] In June 1973, Papadopoulos condemned Constantine as "a collaborator with foreign forces and with murderers" and accused him of "pursuing ambitions to become a political leader".[7] The referendum of 29 July confirmed the end of the Greek monarchy and the end of the reign of Constantine.[68][63] That year, the junta expropriated the palace of Tatoi and offered the king 120 million drachmas, money that Constantine refused.[82]

Restoration of democracy and the referendum

The Turkish invasion of Cyprus led to the downfall of the military regime, and Konstantinos Karamanlis returned from exile to become prime minister. The 1973 republican constitution was regarded as illegitimate, and the new administration issued a decree restoring the 1952 constitution. Constantine expected an invitation to return.[7] On 24 July, he declared his "deep satisfaction with the initiative of the armed forces in overthrowing the dictatorial regime" and welcomed the advent of Karamanlis as prime minister.[83]

Following the appointment of a civilian government in November 1974 after the first post-junta legislative election, Karamanlis called a referendum, held on 8 December 1974, on whether Greece would restore the monarchy or remain a republic.[68] Although he had been the leader of the traditionally monarchist right, Karamanlis made no attempt to encourage a vote in favour of restoring the monarch. The king was not allowed by the government to return to Greece to campaign for the restoration of constitutional monarchy. He was only allowed to broadcast to the Greek people from London on television. Analysts claim this was a deliberate act by the government to reduce the possibility of a vote in favour of restoration.[84]

Constantine, speaking from London, said he had made mistakes in the past. He said he would always be supportive of democracy in future and promised that his mother would stay away from the country.[7] Local monarchists campaigned on his behalf. The vote to restore the monarchy was only about 31% with most of the support coming from the Peloponnese region. Almost 69% of the electorate voted against the restoration of the monarchy and for the establishment of a republic.[7][68][63]

Life in exile after 1974

Constantine remained in exile for 40 years after the vote in favour of the republic, living in Italy and the United Kingdom.[85][63] He returned briefly for the first time in February 1981, which was to attend the funeral of his mother in the family cemetery of the former Royal Palace at Tatoi. The funeral was generally controversial, due to the little empathy generated by Queen Frederica and the royal family, which is why the government authorized him to stay only for six hours in the country.[86] His gesture of kissing the ground upon arrival in Greece was also polemic as it was considered an act of provocation for the antiroyalists.[68][87]

Abortive conspiracies

.jpg.webp)

The posthumously published archives of Konstantinos Karamanlis, as well as the memoirs of Constantine's former marshal of the court, Leonidas Papagos, revealed that from 1975 to 1978, Constantine was involved in a conspiracy to overthrow the democratic government, including the assassination of Karamanlis and a followed referendum on the monarchy.[88] Constantine's close confidant, Michail Arnaoutis, approached high-ranking officers to try to gain their support. After some naval officers approached expressed doubts that Arnaoutis spoke for the former king, the chief engineer of the fleet was invited to London, where Constantine confirmed the basic outline of the plot as relayed by Arnaoutis.[88] The naval officers approached informed Karamanlis, who sent Papagos to warn Constantine to "stop conspiring" and the former monarch denied knowledge of the conspiracy, but when called upon, Arnaoutis confirmed his contacts with officers in Greece in the presence of both Constantine and Papagos.[88] The events were confirmed in 1999 by one of the officers whom Arnaoutis had approached, Vice Admiral Ioannis Vasileiadis, after the publication of Papagos' memoirs. According to Vasileiadis, Arnaoutis said that Constantine had contacted the Shah of Iran in order to prevent possible Turkish military action during the coup.[88][79]

Karamanlis was also alerted to Constantine's suspicious activities by the British secret services, who had apparently taped his conversations with Greek visitors. In October 1976, the Greek prime minister was informed by the British ambassador that Constantine, while not the driving force behind the conspiracy, was very much aware of it and did nothing to discourage it.[88] The British also provided warnings that sympathizers had informed Constantine that a coup would take place in November 1976, led by low-ranking army officers loyal to former dictator Dimitrios Ioannidis. Karamanlis and his chief diplomatic adviser, Petros Molyviatis, applied pressure on both the British and US governments, which led to a personal intervention by British prime minister James Callaghan, who warned Constantine off. The Greek government repeatedly sent envoys to the former king for the same purpose, but he denied any knowledge of the affair.[88] Karamanlis chose not to publicise it in order to not destabilise the fragile democratic system in Greece.[88] Nevertheless, in October 1978, Constantine and Arnaoutis were recorded by Greek agents to have sought contact with military and political leaders, trying to win them over to the cause of a royal restoration.[88]

Legal quarrels over the royal properties

In 1992, Constantine reclaimed all the movable property from the palace of Tatoi, which was transported in containers to the residence of the royal couple in exile amid shouts of citizens.[68][82] That same year, he signed an agreement with the government of Konstantinos Mitsotakis to cede most of his movable property in Greece to a non-profit foundation in the country, in exchange for recovering Tatoi.[82] Two years later, Prime Minister Andreas Papandreou abrogated that agreement and refused to return the properties seized from Constantine, who cancelled the Greek citizenship of both himself and the royal family. That year, the former king had requested the return of the palace of Tatoi to his ownership.[68][82]

In November 2000, Constantine sued Greece at the European Court of Human Rights for compensation for the seized property.[89] He won a much smaller amount, receiving a monetary compensation of €12 million, with a far smaller sum awarded to his sister Irene and his aunt Katherine.[90][68][82]

Constantine, in turn, created the Anna-Maria Foundation to allocate the funds in question back to the Greek people for use in "extraordinary natural disasters" and charitable causes. The court decision also ruled that Constantine's human rights were not violated by the Greek state's decision not to grant him Greek citizenship and passport unless he adopts a surname. Constantine said of this "the law basically said that I had to go out and acquire a name. The problem is that my family originates from Denmark and the Danish royal family haven't got a surname."[91]

Later life

.jpg.webp)

Following the abolition of the monarchy, Constantine repeatedly stated that he recognised the republic, the laws and the constitution of Greece. He told Time, "If the Greek people decide that they want a republic, they are entitled to have that and should be left in peace to enjoy it."[92] Constantine and Anne-Marie for many years lived in Hampstead Garden Suburb, London. Constantine was a close friend of his second cousin Charles III, then Prince of Wales, and a godfather to Charles's son Prince William. Constantine's 60th birthday lunch marked the first time that Charles and Camilla Parker Bowles were seen in public together in a relationship.[80] In 2004, Constantine returned to Greece temporarily during the Athens Olympic Games as a member of the International Olympic Committee.[92] Later that year, when asked whether he thought he would be the last monarch of Greece, Constantine said that it is "very hard" to determine the future.[80]

According to a nationwide 2007 survey of 2,040 households in Greece conducted on behalf of the newspaper To Vima, only 11.6% supported a constitutional monarchy. More than half of the respondents, 50.9%, considered that the dictatorship of the junta had brought benefits to Greece.[93] During the 2008 Beijing and 2012 London Olympics, Constantine, in his role as honorary member of the International Olympic Committee, was the official presenter at the sailing medal ceremonies. He was Co-President of Honour of the International Sailing Federation, along with Harald V of Norway, from 1994 on.[94]

In 2013, Constantine returned to reside in Greece after selling his Hampstead house.[95] In November 2015, his autobiography was published in three volumes by the national newspaper, To Vima.[96] On 10 January 2022, he was admitted to the hospital after testing positive for COVID-19, which he had been fully vaccinated against.[97]

Death

Constantine suffered multiple health problems in his final years, including heart conditions and decreased mobility.[98] On 6 January 2023, he was admitted to the intensive care unit of the private Hygiea hospital in Athens in critical condition after suffering a stroke.[99] He died 4 days later, on 10 January 2023, at the age of 82.[100][101] His death was leaked by Associated Press,[102] but was then announced by his private office.[103] Constantine never formally renounced his title as King of the Hellenes due to Greek Orthodox anointment tradition, which states that a monarch will never lose their status until their death.[80]

By the decision of the Greek government, Constantine was not given a state funeral. The funeral took place on 16 January in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens in the presence of Archbishop Ieronymos II and 200 attendees, including ten current and former European monarchs – Philippe of Belgium, Simeon II of Bulgaria, Margrethe II of Denmark, Henri of Luxembourg, Albert II of Monaco, Beatrix and Willem-Alexander of the Netherlands, Juan Carlos I and Felipe VI of Spain, and Carl XVI Gustaf of Sweden – and members of the royal houses of Baden, Hanover, Iran, Jordan, Liechtenstein, Norway, Romania, Russia, Schleswig-Holstein, Serbia and the United Kingdom. The Greek government was represented by Minister of Culture Lina Mendoni and Deputy Prime Minister Panagiotis Pikrammenos. Constantine was buried in Tatoi next to his parents that same day.[104][105]

Marriage and issue

On 18 September 1964, in a Greek Orthodox ceremony in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens, Constantine married Princess Anne-Marie of Denmark, his third cousin.[53]

Issue

| Name | Birth | Marriage | Children | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Date | Spouse | |||

| Princess Alexia | 10 July 1965 | 9 July 1999 | Carlos Morales Quintana |

|

| Crown Prince Pavlos | 20 May 1967 | 1 July 1995 | Marie-Chantal Miller |

|

| Prince Nikolaos | 1 October 1969 | 25 August 2010 | Tatiana Blatnik | |

| Princess Theodora | 9 June 1983 | |||

| Prince Philippos | 26 April 1986 | 12 December 2020 / 23 October 2021 | Nina Flohr | |

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Constantine II of Greece |

|---|

Titles, styles and honours

Titles and styles

Until 1994, Constantine's official Greek passport identified him as "Constantine, Former King of the Hellenes". A law passed in 1994 stripped him of his Greek citizenship, passport and property. The law stated that Constantine could not be granted a Greek passport unless he adopted a surname. Constantine stated, "I don't have a surname — my family doesn't have a surname. The law that Mr Papandreou passed basically says that he considers that I am not Greek and that my family was Greek only so long as we were exercising the responsibilities of sovereign, and I had to go out and acquire a surname. The problem is that my family originates from Denmark, and the Danish royal family haven't got a surname." Glücksburg, he said, was not a family surname but the name of a town. He said, "I might as well call myself Mr. Kensington."[106]

Constantine freely travelled in and out of Greece on a Danish passport, as Constantino de Grecia (Spanish for 'Constantine of Greece'),[107] because Denmark (upon request) issues diplomatic passports to any descendants of King Christian IX and Queen Louise, and Constantine was a Prince of Denmark in his own right.[108] During his first visit to Greece using this passport, Constantine was mocked by some of the Greek media, which hellenised the "de Grecia" designation and used it as a surname, thus naming him Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Ντεγκρέτσιας, romanized: Konstantínos Degrétsias.[107]

The International Olympic Committee continued to refer to Constantine as His Majesty King Constantine.[109] In Greece, he was referred to as ο τέως βασιλιάς or ο πρώην βασιλιάς ('the former king'). His official website lists his "correct form of address" as King Constantine, former King of the Hellenes.[110]

National honours

.svg.png.webp) Greece

Greece

Grand Cross of the Royal Order of the Redeemer[111] (by birth)

Grand Cross of the Royal Order of the Redeemer[111] (by birth) Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Saints George and Constantine[111]

Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Saints George and Constantine[111] Grand Cross of the Order of George I[111]

Grand Cross of the Order of George I[111] Grand Cross of Order of the Phoenix[111]

Grand Cross of Order of the Phoenix[111] Medal of Military Merit 1st Class[111]

Medal of Military Merit 1st Class[111]- Recipient of the Commemorative Badge of the Centenary of the Royal House of Greece[111]

Foreign honours

Denmark:

Denmark:

- Knight of the Order of the Elephant[111]

- Grand Commander of the Order of the Dannebrog[111]

France: Grand Cross of the Order of the Legion of Honour

France: Grand Cross of the Order of the Legion of Honour Iranian Imperial Family: Recipient of the Commemorative Medal of the 2,500 year celebration of the Persian Empire

Iranian Imperial Family: Recipient of the Commemorative Medal of the 2,500 year celebration of the Persian Empire Italy: Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic[112]

Italy: Grand Cross with Collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic[112] Luxembourg: Knight of the Order of the Gold Lion of the House of Nassau

Luxembourg: Knight of the Order of the Gold Lion of the House of Nassau Netherlands: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the House of Orange

Netherlands: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the House of Orange Norway: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Olav

Norway: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Olav Spain: 1.176th Knight of the Spanish Order of the Golden Fleece

Spain: 1.176th Knight of the Spanish Order of the Golden Fleece Sweden: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Seraphim

Sweden: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Seraphim United States: Commander of the Legion of Merit

United States: Commander of the Legion of Merit

Awards

- Scout Association of Japan Golden Pheasant Award (1964)[113]

- International Sailing Federation Beppe Croce Trophy (2010)[114]

See also

References

- Hourmouzios 1972, p. 155; Van der Kiste 1994, pp. 183–184.

- "Πέθανε ο τέως βασιλιάς Κωνσταντίνος". Kathimerini. 10 January 2023. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- Hope, Kevin (November 2011). "Referendum plan faces hurdles". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 6 January 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "Constantine II", Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition, 2011, archived from the original on 1 December 2011, retrieved 12 November 2011,

On 1 June 1973, the military regime ruling Greece proclaimed a republic and abolished the Greek monarchy. A referendum on July 29, 1973, confirmed these actions. After the election of a civilian government in November 1974, another referendum on the monarchy was conducted on 8 December. The monarchy was rejected, and Constantine, who had protested the vote of 1973, accepted the result.

- Meletis Meletopoulos (1994). "Κωνσταντίνος Β΄",Η βασιλεία στη Νεώτερη Ελληνική Ιστορία. Από τον Όθωνα στον Κωνσταντίνο Β΄ (in Greek). Athens: Nea Synora-AA Livani. p. 196.

- Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh, ed. (1977). Burke's Royal Families of the World. Vol. 1: Europe & Latin America. London: Burke's Peerage Ltd. pp. 327–28. ISBN 0-85011-023-8.

- Curley, W.J.P. (1975). Monarchs In Waiting. London: Hutchinson & Co Ltd. pp. 39–41. ISBN 0-09-122310-5.

- Tantzos 1990, p. 5.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 110-111.

- "Νεόλογος Πατρών". Νεόλογος Πατρών (in Greek). No. 132. 4 June 1940.

- "Naming practices" in British Academy and Oxford University, Lexicon of Greek Personal Names, online Archived 16 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 367.

- da Rocha Carneiro, Monique (2000). La descendance de Frédéric-Eugène duc de Wurtemberg (in French). Paris: Éditions L'intermédiaire des chercheurs et curieux. p. 411. ISBN 978-2-908003-17-8.

- Van der Kiste 1994, p. 159 and 161–162.

- Hourmouzios 1972, p. 116.

- Tantzos 1990, p. 15-16.

- Van der Kiste 1994, p. 162-163.

- Palmer & Greece 1990, p. 80.

- Tantzos 1990, p. 18-20.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 113.

- "Frederica, queen of Greece". Encyclopedia Britannica. 14 April 2023.

- Vickers 2000, p. 292.

- Van der Kiste 1994, p. 164.

- Bertin 1982, p. 338.

- Tantzos 1990, p. 20-21.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 189.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 114.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 113-115.

- Hourmouzios 1972, p. 133.

- Hourmouzios 1972, p. 136 og 144.

- Tantzos 1990, p. 21.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 115-116.

- Van der Kiste 1994, p. 170-171.

- Hourmouzios 1972, p. 164-169 og 171.

- Tantzos 1990, p. 38-39.

- Hourmouzios 1972, p. 155.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 117.

- Tantzos 1990, p. 61.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 359.

- Packard, Ann (10 March 2012). "Obituary: Jocelin Winthrop-Young OBE, the Gordonstoun ethic ran deep in life and work of educationalist and Hahn disciple". The Scotsman..

- "Greek Civil War | Britannica". Encyclopædia Britannica. 13 April 2023.

- Demetris Nellas (11 January 2023). "Constantine, the former and last king of Greece, dies at 82". Associated Press.

- Montgomery-Massingberd, Hugh, ed. (1977). Burke's Royal Families of the World. Vol. 1: Europe & Latin America. London: Burke's Peerage Ltd. pp. 327–28. ISBN 0-85011-023-8.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 127.

- Celada 2007, p. 70.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 120 og 131–132.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 120.

- "Λύκειο Αναβρύτων: Το ιστορικό πρότυπο σχολείο που φοίτησε ο τέως βασιλιάς Κωνσταντίνος". infokids.gr (in Greek). 13 January 2023.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 124-125.

- Hourmouzios 1972, p. 216 og 300.

- "Απεβίωσε ο τέως βασιλιάς Κωνσταντίνος – Μητσοτάκης: «Η Ιστορία θα τον κρίνει δίκαια και αυστηρά»". Euronews (in Greek). 11 January 2023.

- Tantzos 1990, p. 80-81.

- "Ο τέως βασιλιάς Κωνσταντίνος μέσα από το ιστορικό αρχείο της «Κ»". Kathimerini (in Greek). 11 January 2023.

- "Olympic Records World Records". International Olympic Committee. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- "Crown Prince Konstantinos". Sports Reference. 1 March 2020. Archived from the original on 18 April 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "ISA Committee Members". International Soling Association.

- "IDA Officers". International Dragon Association.

- "Ailing Greek King Names Son Regent". The New York Times. 21 February 1964. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- Van der Kiste 1994, p. 184.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano 2004, p. 135-136.

- Tantzos 1990, p. 102-104.

- Dimitrakis 2009, p. 107.

- "Κωνσταντίνος Β': Ο τελευταίος Βασιλιάς της Ελλάδας". Sansimera (in Greek).

- "Κωνσταντίνος Β': Ο τελευταίος Βασιλιάς της Ελλάδας". Kathimerini (in Greek). 14 January 2023.

- Kontogiannis, Panos (18 June 2017). "The July apostasy of 1965 in Greece; a royal coup to the regime of the colonels". Jason Institute for Peace and Security Studies.

- Legg, Keith R. (1969). Politics in Modern Greece. Stanford UP. ISBN 0804707057.

- Maniatis, Dimitris N. (14 January 2023). "Ο Κωνσταντίνος, τα Ιουλιανά του 1965 και ο δρόμος προς τη χούντα". In.gr (in Greek).

- Pantazopoulos, Yannis (13 January 2023). "Οι σκοτεινές σελίδες της ιστορίας του τέως βασιλιά Κωνσταντίνου". Lifo (in Greek).

- Clogg, 1987, pp. 52

- "Τα «Ιουλιανά» του 1965 και η «Αποστασία»". Sansimera (in Greek)..

- Σήμερα .gr, Σαν. "Το Πραξικόπημα της 21ης Απριλίου 1967". Σαν Σήμερα .gr (in Greek). Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- Clogg, 1987, pp. 53

- Pelt, M. (2006). Tying Greece to the West: US-West German-Greek Relations 1949–1974. Studies in 20th & 21st century European history. Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-87-7289-583-3. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- Chrysopoulos, Philip (21 April 2022). "April 21, 1967: Military Junta Places Greece in Shackles". Greek Reporter.

- TV documentary "ΤΑ ΔΙΚΑ ΜΑΣ 60's – Μέρος 3ο: ΧΑΜΕΝΗ ΑΝΟΙΞΗ Archived 6 April 2008 at the Wayback Machine" Stelios Kouloglu

- Dascarolis, Ioannis V. (11 January 2023). "Το στρατιωτικό κίνημα του Βασιλιά Κωνσταντίνου Β΄ κατά της Χούντας (13 Δεκεμβρίου 1967)". HuffPost (in Greek).

- Kafantaris, Dimitris (15 January 2023). "Τέως βασιλιάς Κωνσταντίνος: Το χρυσό Ολυμπιακό μετάλλιο στη Ρώμη και οι γάμοι του". Vradyni (in Greek).

- Hindley, G (1979). The Royal Families of Europe. London: Lyric Books Ltd. pp. 126–127. ISBN 0-07-093530-0.

- "Το βασιλικό πραξικόπημα που δεν έγινε" (in Greek). To Vima. 6 June 1999. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- Constantine II of Greece, Anne-Marie of Greece (2004). Constantine, A King's Story!. London, Athens. Retrieved 2 March 2023.

- "Greek Premier Supplants the Regent". The New York Times. 22 March 1972.

- Giannaka, Sofia (25 November 2008). "Η περιουσία του Τέως". To Vima.

- Eder, Richard (25 July 1974). "Constantine Declines to Predict When He Will Return to Greece". The New York Times.

- "The Referendum". The Royal Chronicles. Archived from the original on 1 November 2020. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- Smith, Helena (15 December 2013). "Greece's former king goes home after 46-year exile". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- Kaissaratos, Panos (12 January 2023). "Τέως Βασιλιάς Κωνσταντίνος: Η κηδεία της μητέρας του, Φρειδερίκης, είχε ανάψει φωτιές". In.gr. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- "Γιατί ο Κωνσταντίνος μίλησε με ντουντούκα στην επεισοδιακή κηδεία της μητέρας του Φρειδερίκης. Η πολιτική κόντρα". Mixanit tou Xronou. 14 January 2023. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- "Η συνωμοσία του Κωνσταντίνου για την «εξουδετέρωση Καραμανλή» – Η αποκάλυψη της «Κ»". Kathimerini (in Greek). 18 January 2023. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- "Ex-king of Greece reclaims his lost palaces". The Guardian. 24 November 2000.

- Helena Smith (29 November 2002). "Court deals decisive blow to deposed Greek royals". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 August 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- Bates, Stephen (12 January 2023). "King Constantine II of Greece obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- "Throneless abroad: The men who would be king". Time. 3 June 2002. Vol. 159 No. 22.

- "The Greeks are looking for a new strong leader". To Vima. Archived from the original on 25 April 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2020.

- "HM King Constantine". GreekRoyalFamily.gr. Archived from the original on 17 February 2012.

- Smith, Helena (15 December 2013). "Greece's former king goes home after 46-year exile". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- "Εξαντλήθηκε και κυκλοφορεί στα περίπτερα ο α' τόμος του «Βασιλεύς Κωνσταντίνος»". To Vima (in Greek). 23 November 2015. Archived from the original on 6 January 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- "King Constantine II Of Greece Admitted To Hospital With Covid-19". 10 January 2022.

- "Former king of Greece, Constantine II, dies at 82". ABC News (Australia). Reuters. 11 January 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- "Τέως βασιλιάς Κωνσταντίνος: Επιδεινώθηκε η υγεία του – Νοσηλεύεται σε κρίσιμη κατάσταση". Kathimerini. 6 January 2023.

- "Last king of Greece, Constantine II, dies aged 82". The Guardian. 10 January 2023. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- Nellas, Demetris. "Constantine, the former and last king of Greece, dies at 82". ABC News. Archived from the original on 11 January 2023. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- "Constantine II, last king of Greece dies at 82". BBC News.

- "Greece's last king, Constantine II, dies at 82". Politico.

- "Former King Constantine was buried in Tatoi next to his parents". Greek City Times. 16 January 2023. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- Kokkinidis, Tasos (13 January 2023). "Greece to Become Royal Hub for Former King Constantine's Funeral". Greek Reporter. Retrieved 14 January 2023.

- Colacello, Bob (July 1995). "King without a country". Vanity Fair. p. 47. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- Βραβορίτου, Αγνή (25 April 2003). Δεν περνάει η μπογιά του. Eleftherotypia (in Greek). Χ. Κ. Τεγόπουλος Εκδόσεις Α.Ε. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 1 September 2011.

- "2000–01, 1. samling – Svar på § 20-spørgsmål: Om kong Konstantin har dansk pas. Spm. nr. S 3937: Til justitsministeren". Folketinget Archive. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- HM King Constantine Archived 13 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine. International Olympic Committee. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- "FAQ". Official website of the Greek royal family. Archived from the original on 3 June 2020. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

The correct form of address is: King Constantine, former King of the Hellenes and so on for the family members.

- "ROYAL JEWELS OF REMEMBRANCE FOR THE LATE KING CONSTANTINE II". thecourtjeweller.com. 29 January 2023. Archived from the original on 17 June 2023. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- "Le onorificenze della Repubblica Italiana". quirinale.it.

- 䝪䞊䜲䝇䜹䜴䝖日本連盟 きじ章受章者 [Recipient of the Golden Pheasant Award of the Scout Association of Japan] (PDF). Reinanzaka Scout Club (in Japanese). 23 May 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2020.

- "Official Website: Beppe Croce". Sailing. 21 February 2012. Archived from the original on 25 September 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

Bibliography

- Bertin, Celia (1982). Marie Bonaparte. Paris: Perrin. ISBN 2-262-01602-X..

- Celada, Eva (2007). Irene de Grecia: La princesa rebelde (in Spanish). Plaza & Janés. ISBN 978-84-01-30545-0.

- Dimitrakis, Panagiotis (2009). Greece and the English. British Diplomacy and the Kings of Greece. London: Tauris Academic Studies. ISBN 978-1-84511-821-1.

- Hourmouzios, Stelio (1972). No Ordinary Crown. A Biography of King Paul of the Hellenes. Weidenfeld & N. ISBN 0-297-99408-5.

- Mateos Sáinz de Medrano, Ricardo (2004). La Familia de la Reina Sofía, La Dinastía griega, la Casa de Hannover y los reales primos de Europa (in Spanish). Madrid: La Esfera de los Libros. ISBN 978-8-4973-4195-0. OCLC 55595158.

- Palmer, Alan; Greece, Michael of (1990). The Royal House of Greece. London: Weidenfeld Nicolson Illustrated. ISBN 978-0-2978-3060-3.

- Tantzos, Nicholas (1990). H.M. Konstantine XIII : King of the Hellenes. Atlantic International Publications. ISBN 0-938311-12-3.

- Van der Kiste, John (1994). Kings of the Hellenes. The Greek Kings, 1863-1974. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7509-2147-3..

- Vickers, Hugo (2000). Alice: Princess Andrew of Greece. St. Martin's Griffin. ISBN 9780312302399.

Further reading

- Constantine II of Greece (2015). "Βασιλεύς Κωνσταντίνος". Athens: To Vima. ISBN 978-960-503-693-5.

- Woodhouse, C.M. (1998). Modern Greece a Short History. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 0-571-19794-9.

- Αλέξης Παπαχελάς (1997). Ο βιασμός της ελληνικής δημοκρατίας. Athens:Εστία. ISBN 960-05-0748-1.

- Γιάννης Κάτρης (1974). Η γέννηση του νεοφασισμού στην Ελλάδα 1960–1970. Athens: Παπαζήση.

- Καδδάς, Αναστάσιος Γ. (2010). "Η Ελληνική Βασιλική Οικογένεια". Athens: Εκδόσεις Φερενίκη. ISBN 978-960-9513-03-6.

External links

- Official website of the Greek Royal Family

- HM King Constantine at Olympics.com

- Crown Prince Constantine at the Hellenic Olympic Committee

- Crown Prince Konstantinos at Olympedia

- H.R.H. Konstantin of Greece at World Sailing

- ΜΑΡΙΟΣ ΠΛΩΡΙΤΗΣ:Απάντηση στον Γκλύξμπουργκ, Εφημερίδα Το ΒΗΜΑ, Κυριακή 10 Ιουνίου 2001 – Αρ. Φύλλου 13283

- ΜΑΡΙΟΣ ΠΛΩΡΙΤΗΣ:Δευτερολογία για τον Γκλύξμπουργκ, Εφημερίδα Το ΒΗΜΑ, Κυριακή 24 Ιουνίου 2001 – Αρ. Φύλλου 13295

- ΣΤΑΥΡΟΣ Π. ΨΥΧΑΡΗΣ: H ΣΥΝΤΑΓΗ ΤΗΣ ΚΡΙΣΗΣ, Εφημερίδα Το ΒΗΜΑ, 17/10/2004 – Κωδικός άρθρου: B14292A011 ID: 265758

.svg.png.webp)