Contact tracing

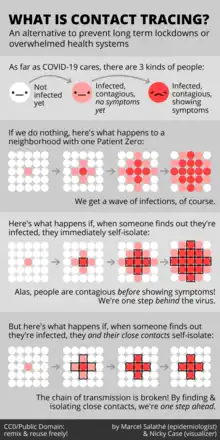

In public health, contact tracing is the process of identifying persons who may have been exposed to an infected person ("contacts") and subsequent collection of further data to assess transmission.[1][2] By tracing the contacts of infected individuals, testing them for infection, and isolating or treating the infected, this public health tool aims to reduce infections in the population.[2] In addition to infection control, contact tracing serves as a means to identify high-risk and medically vulnerable populations who might be exposed to infection and facilitate appropriate medical care.[1] In doing so, public health officials utilize contact tracing to conduct disease surveillance and prevent outbreaks.[2] In cases of diseases of uncertain infectious potential, contact tracing is also sometimes performed to learn about disease characteristics, including infectiousness.[1][2] Contact tracing is not always the most efficient method of addressing infectious disease.[2] In areas of high disease prevalence, screening or focused testing may be more cost-effective.[1][2]

The goals of contact tracing include:[3]

- Interrupting ongoing transmission and reduce the spread of an infection

- Alerting contacts to the possibility of infection and offer preventive services or prophylactic care

- Offering diagnosis, counseling and treatment to already infected individuals

- If the infection is treatable, helping prevent reinfection of the originally infected patient

- Learning about the epidemiology of a disease in a particular population

- Being a tool in multifaceted prevention strategy to effectively curb the spread of an infectious disease.

History

Contact tracing programs were first implemented to track syphilis cases in the 1930s.[4] Initial efforts proved to be difficult given the stigmatization associated with sexually transmitted infections (STIs).[4] Individuals were reluctant to report infections because they were concerned for their privacy.[5] Revealing partner history and details about sexual activity was challenging as it affected relationships among individuals and community members.[4][5] In addition, public health officials targeted certain populations such as sex workers, minorities, and at-risk populations further eliciting feeling of fear, shame, and guilt in society.[4] With these negative implications of contact tracing, particularly in the space of sexually transmitted infections, public health officials found it difficult to elicit information from exposed individuals.[2] During the HIV epidemic, many affected person were hesitant to report information, which hindered the efforts to understand HIV and curb the spread.[2] To combat some of the negative stigma associated with contact tracing and STIs, health departments sometimes referred to contact tracing as partner notification in the 1980s.[4][5] Partner notification, also called partner care, is a subset of contact tracing aimed specifically at informing sexual partners of an infected person and addressing their health needs.[2] This definition evolved from identifying infected individuals to including a comprehensive program that encompasses counseling and medical care to treat the infection.[4]

The official title, contract tracers, was first implemented in the United Kingdom during the smallpox outbreaks.[6] Dedicated individuals served on a surveillance-based team to curb the spread of disease.[6] This process served as a blueprint for other public health agencies to have a formalized program.[6] The United States soon followed and enacted a contact tracing program for the prevention of infectious diseases which included TB, HIV, SARS, and now SARS-CoV-2.[6]

Steps

Contact tracing generally involves the following steps as provided by CDC:[7]

- Notification of exposure: An individual is identified as having a communicable disease (often called the index case).[7] This case may be reported to public health or managed by the primary health care provider.[7] Ideally, all notification should be done within 24 hours of exposure.[7] If contacts are not individually identifiable (e.g. members of the public who attended the same location), broader communications may be issued, like media advisories.[7] Communication with the contacts will be initially done through digital methods including texts and email.[7] Efforts to inform the contacts remotely should be exhausted before considering an in-person communication.[7] During this process, it is imperative that the identity of the source of exposure must not be revealed to the contact.[7]

- Contact interview: The index case is interviewed to learn about their movements, whom they have been in close contact with or who their sexual partners have been.[7] Depending on the disease and the context of the infection, family members, health care providers, and anyone else who may have knowledge of the case's contacts may also be interviewed.[7] Interviews typically follow a template which include demographics, symptomology, pre-existing conditions, and timing of exposures to ensure consistency across all contact tracing efforts.[8] Interpreters and source materials in different languages are utilized to accommodate persons with different cultural backgrounds.[7]

- Recommendations for close contacts: Once contacts are identified, public health workers contact them to offer counseling, screening, prophylaxis, and/or treatment.[7] Contacts are provided education on concepts of quarantine, isolation, signs and symptoms of disease, and timely testing.[7] If applicable, contacts should wear appropriate personal protective equipment to reduce to transmission of disease.[7]

- Assessing feasibility of self-quarantine and support: Contacts may be isolated (e.g. required to remain at home) or excluded (e.g. prohibited from attending a particular location, like a school) if deemed necessary for disease control.[7] Challenges for this process include access to resources during quarantine such as food, water, and safe living environment.[7] People with special roles lack the convenience practicing quarantine given their daily responsibilities.[7] Examples include, single parents, caregivers, and individuals with toddlers. Social services and ancillary support from the government become crucial to maintaining measures of quarantine and isolation.[7] Contacts should be made aware whether or not the quarantine or isolation is voluntary or mandatory.[7] Depending on the nature of the disease of interest, governments can issue legal orders to maintain integrity of contact tracing.[7]

- Medical monitoring: Although contact tracing can be enhanced by letting patients provide information, medication, and referrals to their contacts, evidence demonstrates that direct public health involvement in notification is most effective.[9] Ideally, contacts are checked upon daily for signs and symptoms of disease by contact racers.[7] An alternative would be having the contacts report daily to their assigned official. This is usually done through digital platforms such as email and text.[7] If a contact is symptomatic, a case investigator is assignment to direct the individual to the appropriate testing and treatment.[7] This stage of contact tracing is highly dependent on resource availability.[7]

- Contact close out: This stage is dependent on the duration of quarantine for people with and without symptoms.[7] The ideal number of days for quarantine and isolation are determined by the health agencies.[7] Once the contact adequately completes the quarantine/isolation for the defined number of days, they can be closed out.[7] Next steps such as returning to work and participating in social activities are discussed.[7]

Application

.jpg.webp)

Contact types

The types of contacts that are relevant for public health management vary because of differing modes of transmission.[10] For sexually transmitted infections, sexual contacts of the index case are relevant, as well as any babies born to the index case.[10] This information is crucial for investigating congenital syphilis cases for example.[10] For blood-borne infections, blood transfusion recipients, contacts who shared a needle, and anyone else who could have been exposed to the blood of the index case are relevant.[10] This information becomes relevant for health systems to keep track of high risk populations and medical errors, unavoidable and preventable.[10] For pulmonary tuberculosis, people living in the same household or spending a significant amount of time in the same room as the index case are relevant.[10] Understanding the pathology and transmissibility of the disease guides the approach to contact tracing strategy.[10]

Outbreaks

Although contact tracing is most commonly used for control of diseases, it is also a critical tool for investigating new diseases or unusual outbreaks.[10] For example, as was the case with SARS, contact tracing can be used to determine if probable cases are linked to known cases of the disease, and to determine if secondary transmission is taking place in a particular community.[11]

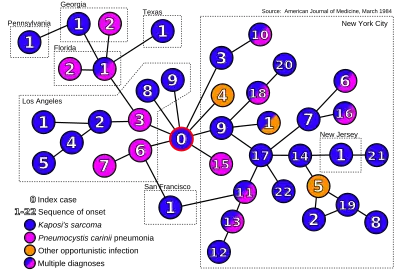

Contact tracing has also been initiated among flight passengers during the containment phase of larger pandemics, such as the 2009 pandemic H1NI influenza.[12] Contact tracing played a major role in investigating Ebola virus in the UK in 2014 and monkeypox in the UK in 2018.[13] The eradication of smallpox, for example, was achieved by exhaustive contact tracing to find all infected persons.[14] This was followed by isolation of infected individuals and immunization of the surrounding community and contacts at-risk of contracting smallpox.[14] Contact tracing can help identify the etiology of a disease outbreak.[15] In 1984, contact tracing provided the first direct evidence that AIDS may be spread by an infectious agent during sexual contacts.[16][17] The infective agent has since been identified as HIV.[18]

Diseases for which contact tracing is commonly performed include tuberculosis, vaccine-preventable infections like measles, sexually transmitted infections (including HIV), blood-borne infections, Ebola, bacterial infections, and novel virus infections (e.g., SARS-CoV, H1N1, and SARS-CoV-2).[2] Contact tracing has been a pillar of communicable disease control in public health for decades.[2] With each outbreak and disease presenting with its own challenges, contact tracing is an adaptable tool used by authorities to identify, notify, and curb transmission of infections.[2]

Backward and forward tracing

Backward (or reverse) tracing seeks to establish the source of an infection, by looking for contacts before infection.[19] It can be used when a source of the infection is unknown and in situations of minimally monitored settings.[19] The goal is identify the exposures associated with the index case and secondary exposures of those contact to halt the cycle of transmission.[19] During the COVID-19 pandemic, the adoption by Japan in early spring 2020 of an approach focusing on backward contact tracing was hailed as successful,[20][21][22][23] and other countries which managed to keep the epidemic under control, such as South Korea[24] and Uruguay,[25][26] are said to have also used the approach.[27] In the United States, contact tracing had suboptimal impact on SARS-CoV-2 transmission, largely because 2 of 3 cases were either not reached for interview or named no contacts when interviewed.[28] Engagement in contact tracing was positively correlated with isolation and quarantine.[29] However, most adults with COVID-19 isolated and self-notified contacts regardless of whether the public health workforce was able to reach them. Identifying and reaching contacts was challenging and limited the ability to promote quarantining, and testing.

Forward tracing is the process of looking for contacts after infection, so as to prevent further disease spread.[19] It is the more conventional way to investigate cases and inform close contacts to either quarantine or isolate.[19]

For epidemics with high heterogeneity in infectiousness, adopting a hybrid strategy of forward contact tracing combined with contact tracing backwards is often used.[19] Backward contact tracing is beneficial for identifying clusters of spreader events, while forward tracing can be used mitigate future transmission.[19] The effectiveness of both approaches is limited by the resources dedicated to contact tracing.[19] Journalist and author Laurie Garrett pointed out in late October 2020, however, that the amount of the virus in the U.S. is now so large that no health departments has the resources to contact and trace.[30] Additionally, officials overlooked the effect of mistrust in the government and conspiracy theories regarding the virus on thwarting contact tracing efforts in the U.S.[31]

COVID-19

Contact tracing requires tremendous resources and work hours to effectively contain an infection.[32] The COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented period where contact tracing and public health efforts were put to the test.[32] Creative strategies were used to sustain public health efforts.[32] Non-health personnel and volunteers were used to meet the shortage of contact tracers.[32] Existing infrastructure such as call centers and national helpline services were used for operations.[32] Individuals who were the most sick and medically vulnerable were prioritized as contacts over healthier people.[32] The advent of technology and digital tracing tools were implemented at a global scale without much vetting and testing.[33] Various countries had different adaptations and outcomes with contact tracing.[32] China used pre-existing WeChat and Alipay platforms to track person health status and travel patterns.[32][33] Singapore, South Korea, and Vietnam had success limiting the initial spread of the virus.[32] With contact tracing, once a person was identified to be exposed, they were immediately isolated. In some instances the government provided housing for isolation to limit movements.[32] In Turkey, the government launched a public forum that highlighted risk zones in various regions of the country.[32] Residents can self-report their health status and track areas with reported high rates of transmission.[32] In the United States, contact tracing efforts varied by the respective health department in a particular state.[32] Overall, effectiveness of contact tracing data in the country was determined by the caseload assigned to contact tracers.[32] When on-demand testing was promoted, increases in negative tests were followed by increases in hospitalizations. Subsequent studies of cases and deaths found the same results. If increased testing were in response to surges, more testing should follow increases in cases, not precede them. An average of 208 extra miles were accumulated in the week following each negative test in U.S. counties. These results suggest that people who tested negative underestimated the risk of exposure when they traveled or visited. <Robertson, LS. Roads to COVID-19 Containment and Spread. </New York: Austin Macauley, 2023.> As self-administered, home-based tests became increasingly used as the primary method to detect SARS-CoV-2, fewer cases were reached for case investigation and contact tracing by public health departments. As a result, fewer cases followed followed contemporary isolation recommendations.[34]

Technology

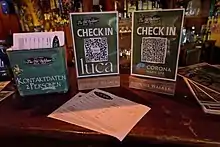

The age of digital contact tracing started gaining traction during the COVID-19 pandemic.[35] With widespread transmission and shortage of contact tracers, technology serves as a resource to bridge gaps.[35] In addition, digital applications automate the process and replace the manual steps contact tracers take to track and notify exposed individuals.[35] There are few benefits of using digital contract tracing apps over the traditional manual methods.[35] Manual methods require a skilled workforce who put in significant hours to diligently follow the steps in contact tracing.[36] This requires a heavy investment from the government, which at times is not feasible.[36] Manual contact tracing is not suited to detect exposures unknown to the contact, as the process is limited to the interview and known knowledge.[36] Areas such as restaurants and malls make it almost impossible for the contact to know whether they have been exposed.[36] At a theoretical scale, digital applications propose mechanism to effectively prevent and stop epidemics.[36]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, manual contact tracers used technology to augment their tracing efforts.[37] Case managers in particular were a group of professionals that benefited from this resource.[37] Case management software is often used by contact tracers to maintain records of cases and contact tracing activities.[37] This is typically a cloud database that may have specialized features such as the ability to use SMS or email directly within the software to notify people believed to have been in close contact with someone carrying an infectious disease.[38] Utilizing a database, provides benefit to track persons of interest and offers a platforms to look at data points such as race, zip code, and symptoms.[38] Vendors offering contact tracing case management software include Salesforce, Microsoft and Watkyn.[39][40][41]

.jpg.webp)

Software

South Korea became a pioneer in utilizing digital contact tracing tools.[42] Learning lessons from the MERS outbreak in 2015, the government executed a robust contact tracing program.[42] Global positioning system (GPS) technology was used to track movement of individuals and appropriately notify persons who have been exposed.[42] The South Korean government launched the Corona 100m application to implement their digital contact tracing measures.[42] The application allowed the public health agencies to track super spreader events, inform the public, and guide them to treatment if applicable.[42] At the end of April 2020, South Korea reported over 10,000 infections and 204 deaths, numbers which were vastly superior to contemporaries in the European Union.[42]

Singapore was among the first countries to use Bluetooth technology in their contact tracing efforts.[42] They launched the application—TraceTogether—which allowed smartphones to provide proximity information useful for contact tracing .[43][36] Unlike South Korea, which utilized a central database to track cases, the Bluetooth-based apps reported information to an encrypted database that automatically deleted information after 14 days.[43] The western world shortly followed and started developing their own Bluetooth-based applications.[43] Facebook Labs patented the use of Bluetooth on smartphones for this in 2018.[44] On 10 April 2020, Apple and Google, which account for most of the world's mobile operating systems, announced COVID-19 apps for iOS and Android.[45] Relying on Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) wireless radio signals for proximity information,[46] the new tools would warn people that they had been in contact with who are infected by SARS-CoV-2.[45][47]

Limitations

With the use of technology, certain limitations and challenges come with the territory.[48][49] Tracking technology might not accurately notify individuals who have been exposed.[48][49] Bluetooth does not differentiate between walls and structure, prompting incorrect notification of exposures. For instance, people separated by walls in an office building can be notified as exposed, even if they never interfaced with the contact.[48][49] Moreover, the parameters set by the developers to contact trace vary and can miss potential cases.[48][49] Such parameters include proximity or distance to trigger an exposure and the timeframe in which contacts are considered to be infectious (usually 14 days).[48][49] Smartphone applications require people having access to smartphones and a competent infrastructure to provide internet access to the public.[48][49] Not all countries can provide these services to their residents.[48][49] Compliance is also a factor.[48] Individuals must download the application, navigate the technology, and follow appropriate directions when notified.[49] This becomes highly difficult when the use of smartphone applications is not mandated.[49] Cohort studies which looked at the efficacy of digital contact tracing reported limited sensitivity in accurately catching cases due to the limitations mentioned above.[48][49] In Pennslyvania, a digital exposure notification app for COVID-19 was downloaded by 5.7% of population (635,612 people).[50] Unfortunately, only 0.1% of all reported cases in Pennsylvania used the app to notify their potential contacts of exposure during the study period (390 persons), resulting in 233 notifications as compared an estimated 573,298 eligible contacts.[51]

Ethical and legal issues

Challenges with contact tracing can arise related to issues of medical privacy and confidentiality.[9] Public health practitioners often are mandated reporters, required to act to contain a communicable disease within a broader population and also ethically obliged to warn individuals of their exposure.[9] Simultaneously, infected individuals have a recognized right to medical confidentiality.[9] Public health teams typically disclose the minimum amount of information required to achieve the objectives of contact tracing.[9] For example, contacts are only told that they have been exposed to a particular infection, but not informed of the person who was the source of the exposure.[9] In the United States, HIPAA is a legal measure for protecting health information.[52] This ensures sharing of only relevant information in the contact tracing process.[52] However, given the unprecedented spread and mortality of SARS-CoV2, advocacy groups argue the protections offered by HIPAA are spread thin.[52] Some activists and health care providers have expressed concerns that contact tracing may discourage persons from seeking medical treatment for fear of loss of confidentiality and subsequent stigma, discrimination, or abuse.[9] This has been of particular concern regarding contact tracing for HIV.[9] Public health officials have recognized that the goals of contact tracing must be balanced with the maintenance of trust with vulnerable populations and sensitivity to individual situations.[9]

Privacy is still a concern even if individual information is not disclosed by public health practitioners.[53] The data collected in databases by governments and tech companies could be utilized for unrelated purposes.[53] Big tech companies have access to data which provides insight on where people visit, what types of interests they pursue, and who interacts with each other.[53] Therefore, questions regarding the extent of data collected, how long the information is stored, who it is shared with, and for what purpose it is being utilized come with serious ethical considerations.[53] Contact tracing efforts miss vulnerable and under resourced populations.[53] Manual tracing efforts face difficulty tracking hard to reach individuals given social complexities.[53] Digital tools require a smart phone and a reliable internet connection, two factors that might exclude certain individuals from benefiting from the technology.[53] Data is still pre-mature as to the efficacy of digital tools.[53] Some stakeholders argue whether it is appropriate to shift contact tracing into a complete digital capacity.[54]

Safeguards become topics of contention when designing digital contact tracing tools.[54] Restrictions on which tracking software such as GPS, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth are used and when those services are turned on are debated among stakeholders.[54] Who has access to the date is an important ethical issue as well.[54] Centralized vs. de-centralized databases have been implemented across the world during the COVID-19 pandemic.[54] The culture within a nation and those who run the government have a huge role in deciding in what players have access to data.[54] Therefore, governing bodies have to consider ethical principles related to transparency and accountability to the public.[54][55] Moreover, whether participating in contact tracing efforts should be voluntary or mandatory is another ethical dilemma that adds to the complexity of implementation.[54] As noted above, there are numerous ethical and legal factors that go into implementation of contact tracing.[54] Executing a robust contact tracing program requires resources, skilled professionals, and an ethical framework that complies with the fabric of a particular nation.[54]

See also

References

- "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Contact tracing". www.who.int. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- Brandt AM (August 2022). "The History of Contact Tracing and the Future of Public Health". American Journal of Public Health. 112 (8): 1097–1099. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2022.306949. PMC 9342804. PMID 35830671.

- "Health Departments". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-02-11. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- "Reflections on the History of Contact Tracing". O'Neill. 2020-07-13. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- "Reflections on the History of Contact Tracing". O'Neill. 2020-07-13. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- "What is Contract Tracing and How Does it Effect Public Health?". Online Masters in Public Health. 2020-10-15. Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- "Health Departments". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-02-11. Retrieved 2022-11-03.

- "Health Departments". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-02-11. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- Ontario Provincial Infectious Diseases Advisory Committee (2009). Sexually transmitted infections best practices and contact tracing best practice recommendations. Toronto, Canada: Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care. ISBN 978-1-42497946-2.

- Australasian Contact Tracing Manual. Darlinghurst, New South Wales, Australia: Australasian Society for HIV Medicine. 2010. ISBN 978-1-920773-95-3.

- "Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) – multi-country outbreak". Global Alert and Response. WHO. Archived from the original on 2003-06-18. Retrieved 2013-05-28.

- Ferretti L, Wymant C, Kendall M, Zhao L, Nurtay A, Abeler-Dörner L, et al. (May 2020). "Quantifying SARS-CoV-2 transmission suggests epidemic control with digital contact tracing". Science. 368 (6491): eabb6936. doi:10.1126/science.abb6936. PMC 7164555. PMID 32234805.

- Keeling, Matt J.; Hollingsworth, T. Deirdre; Read, Jonathan M. (October 2020). "Efficacy of contact tracing for the containment of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19)". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 74 (10): 861–866. doi:10.1136/jech-2020-214051. PMC 7307459. PMID 32576605.

- Scutchfield FD (2003). Principles of public health practice. Clifton Park, New York: Delmar Learning. p. 71. ISBN 0-76682843-3.

- Riley S, Fraser C, Donnelly CA, Ghani AC, Abu-Raddad LJ, Hedley AJ, et al. (June 2003). "Transmission dynamics of the etiological agent of SARS in Hong Kong: impact of public health interventions". Science. 300 (5627): 1961–1966. Bibcode:2003Sci...300.1961R. doi:10.1126/science.1086478. PMID 12766206.

- Klovdahl AS (1985-01-01). "Social networks and the spread of infectious diseases: the AIDS example". Social Science & Medicine. 21 (11): 1203–1216. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(85)90269-2. PMID 3006260.

- Auerbach DM, Darrow WW, Jaffe HW, Curran JW (March 1984). "Cluster of cases of the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Patients linked by sexual contact". The American Journal of Medicine. 76 (3): 487–492. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(84)90668-5. PMID 6608269.

- Blattner W, Gallo RC, Temin HM (July 1988). "HIV causes AIDS". Science. 241 (4865): 515–516. Bibcode:1988Sci...241..515B. doi:10.1126/science.3399881. PMID 3399881.

- "Welcome". Public Health Ontario. Retrieved 2022-11-10.

- "The 'Japan model' that tackled coronavirus". Financial Times.

- Nishimura Y (2020-07-07). "Opinion | How Japan Beat Coronavirus Without Lockdowns". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 2020-10-19.

- Oshitani H (November 2020). "Cluster-Based Approach to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Response in Japan, from February to April 2020". Japanese Journal of Infectious Diseases. 73 (6): 491–493. doi:10.7883/yoken.JJID.2020.363. PMID 32611985. S2CID 220310375.

- "[Addendum] Japan's Cluster-based Approach" (PDF). Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2020-05-28.

- Lee SW, Yuh WT, Yang JM, Cho YS, Yoo IK, Koh HY, et al. (August 2020). "Nationwide Results of COVID-19 Contact Tracing in South Korea: Individual Participant Data From an Epidemiological Survey". JMIR Medical Informatics. 8 (8): e20992. doi:10.2196/20992. PMC 7470235. PMID 32784189.

- Taylor L (September 2020). "Uruguay is winning against covid-19. This is how". BMJ. 370: m3575. doi:10.1136/bmj.m3575. PMID 32948599. S2CID 221778076.

- Moreno, Pilar; Moratorio, Gonzalo; Iraola, Gregorio; Fajardo, Álvaro; Aldunate, Fabián; Pereira-Gómez, Marianoel; Perbolianachis, Paula; Costábile, Alicia; López-Tort, Fernando; Simón, Diego; Salazar, Cecilia; Ferrés, Ignacio; Díaz-Viraqué, Florencia; Abin, Andrés; Bresque, Mariana; Fabregat, Matías; Maidana, Matías; Rivera, Bernardina; Cruces, María E.; Rodríguez-Duarte, Jorge; Scavone, Paola; Alegretti, Miguel; Nabón, Adriana; Gagliano, Gustavo; Rosa, Raquel; Henderson, Eduardo; Bidegain, Estela; Zarantonelli, Leticia; Piattoni, Vanesa; Greif, Gonzalo; Francia, María E.; Robello, Carlos; Durán, Rosario; Brito, Gustavo; Bonnecarrere, Victoria; Sierra, Miguel; Colina, Rodney; Marin, Mónica; Cristina, Juan; Ehrlich, Ricardo; Paganini, Fernando; Cohen, Henry; Radi, Rafael; Barbeito, Luis; Badano, José L.; Pritsch, Otto; Fernández, Cecilia; Arim, Rodrigo; Batthyány, Carlos (2020-07-27). "An effective COVID-19 response in South America: the Uruguayan Conundrum". doi:10.1101/2020.07.24.20161802. S2CID 220793010.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Crozier A, Mckee M, Rajan S (November 2020). "Fixing England's COVID-19 response: learning from international experience". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 113 (11): 422–427. doi:10.1177/0141076820965533. PMC 7686527. PMID 33058751. S2CID 222839822.

- Lash, R. Ryan; Moonan, Patrick K.; Byers, Brittany L.; Bonacci, Robert A.; Bonner, Kimberly E.; Donahue, Matthew; Donovan, Catherine V.; Grome, Heather N.; Janssen, Julia M.; Magleby, Reed; McLaughlin, Heather P.; Miller, James S.; Pratt, Caroline Q.; Steinberg, Jonathan; Varela, Kate (2021-06-03). "COVID-19 Case Investigation and Contact Tracing in the US, 2020". JAMA Network Open. 4 (6): e2115850. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.15850. ISSN 2574-3805. PMC 8176334. PMID 34081135.

- Oeltmann, John E.; Vohra, Divya; Matulewicz, Holly H.; DeLuca, Nickolas; Smith, Jonathan P.; Couzens, Chandra; Lash, R. Ryan; Harvey, Barrington; Boyette, Melissa; Edwards, Alicia; Talboy, Philip M.; Dubose, Odessa; Regan, Paul; Taylor, Melanie M.; Moonan, Patrick K. (2023-07-26). "Isolation and Quarantine for Coronavirus Disease 2019 in the United States, 2020-2022". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 77 (2): 212–219. doi:10.1093/cid/ciad163. ISSN 1537-6591. PMID 36947142.

- "Laurie Garrett: The amount of virus in the U.S. Is so large that 'no one has health departments large enough to do contact tracing'". MSNBC.

- Mueller B (2020-10-03). "Contact Tracing, Key to Reining In the Virus, Falls Flat in the West". The New York Times. Retrieved 2021-04-19.

- Koçak, Cemal (August 2021). "COVID-19 Isolation and Contact Tracing with Country Samples: A Systematic Review". Iranian Journal of Public Health. 50 (8): 1547–1554. doi:10.18502/ijph.v50i8.6800. ISSN 2251-6085. PMC 8643526. PMID 34917525.

- Min-Allah, Nasro; Alahmed, Bashayer Abdullah; Albreek, Elaf Mohammed; Alghamdi, Lina Shabab; Alawad, Doaa Abdullah; Alharbi, Abeer Salem; Al-Akkas, Noor; Musleh, Dhiaa; Alrashed, Saleh (October 2021). "A survey of COVID-19 contact-tracing apps". Computers in Biology and Medicine. 137: 104787. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2021.104787. ISSN 1879-0534. PMC 8379000. PMID 34482197.

- Moonan, Patrick K.; Smith, Jonathan P.; Borah, Brian F.; Vohra, Divya; Matulewicz, Holly H.; DeLuca, Nickolas; Caruso, Elise; Loosier, Penny S.; Thorpe, Phoebe; Taylor, Melanie M.; Oeltmann, John E. (2023). "Home-Based Testing and COVID-19 Isolation Recommendations, United States - Volume 29, Number 9—September 2023 - Emerging Infectious Diseases journal - CDC". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 29 (9): 1921–1924. doi:10.3201/eid2909.230494. PMC 10461662. PMID 37579512.

- "The Tech Behind COVID-19 Contact Tracing". www.gao.gov. 2020-07-28. Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- Shahroz, Muhammad; Ahmad, Farooq; Younis, Muhammad Shahzad; Ahmad, Nadeem; Kamel Boulos, Maged N.; Vinuesa, Ricardo; Qadir, Junaid (September 2021). "COVID-19 digital contact tracing applications and techniques: A review post initial deployments". Transportation Engineering. 5: 100072. doi:10.1016/j.treng.2021.100072. ISSN 2666-691X. PMC 8132499.

- "Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2020-06-17. Retrieved 2020-07-18.

- "ContactPath by Watkyn Launches to Reduce the Spread of COVID-19". prnewswire.com (Press release). Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- "Marc Benioff says 35 states are now using Salesforce's contact tracing technology for coronavirus". cnbc.com. 2020-06-25. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- "Greater Manchester plans case management for contact tracing". ukauthority.com. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- "Contact Tracing Platform Developed in QuickBase". insightfromanalytics.com. 2020-07-14. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- O’Connell, James; O’Keeffe, Derek T. (2021-08-05). "Contact Tracing for Covid-19 — A Digital Inoculation against Future Pandemics". New England Journal of Medicine. 385 (6): 484–487. doi:10.1056/NEJMp2102256. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 34010529. S2CID 234791641.

- Prasad, Aarathi (May 2016). Privacy-preserving controls for sharing mHealth data (Thesis).

- WO 2019139630, "Proximity-based trust", issued 2018-01-16, assigned to Facebook Inc.

- Sherr I, Nieva R (2020-04-10). "Apple and Google are building coronavirus tracking tech into iOS and Android – The two companies are working together, representing most of the phones used around the world". CNET. Archived from the original on 2020-04-10. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- "Contact Tracing – Bluetooth Specification" (PDF). covid19-static.cdn-apple.com (Preliminary ed.). 2020-04-10. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-04-10. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- Heberlein M (2020-01-04). "Kommentar: Mit Corona-App zurück zum halbwegs normalen Leben". Tagesschau.de (in German). Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- Vogt, Florian; Haire, Bridget; Selvey, Linda; Katelaris, Anthea L.; Kaldor, John (2022-03-01). "Effectiveness evaluation of digital contact tracing for COVID-19 in New South Wales, Australia". The Lancet Public Health. 7 (3): e250–e258. doi:10.1016/S2468-2667(22)00010-X. ISSN 2468-2667. PMC 8816387. PMID 35131045. S2CID 246531615.

- Anglemyer, Andrew; Moore, Theresa HM; Parker, Lisa; Chambers, Timothy; Grady, Alice; Chiu, Kellia; Parry, Matthew; Wilczynska, Magdalena; Flemyng, Ella; Bero, Lisa (2020-08-18). Cochrane Public Health Group (ed.). "Digital contact tracing technologies in epidemics: a rapid review". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (8): CD013699. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD013699. PMC 8241885. PMID 33502000.

- Jeon, Seonghye; Rainisch, Gabriel; Harris, A.-Mac; Shinabery, Jared; Iqbal, Muneeza; Pallavaram, Amar; Hilton, Stacy; Karki, Saugat; Moonan, Patrick K.; Oeltmann, John E.; Meltzer, Martin I. (February 2023). "Estimated Cases Averted by COVID-19 Digital Exposure Notification, Pennsylvania, USA, November 8, 2020-January 2, 2021". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 29 (2): 426–430. doi:10.3201/eid2902.220959. ISSN 1080-6059. PMC 9881797. PMID 36639132.

- Jeon, Seonghye; Rainisch, Gabriel; Harris, A.-Mac; Shinabery, Jared; Iqbal, Muneeza; Pallavaram, Amar; Hilton, Stacy; Karki, Saugat; Moonan, Patrick K.; Oeltmann, John E.; Meltzer, Martin I. (February 2023). "Estimated Cases Averted by COVID-19 Digital Exposure Notification, Pennsylvania, USA, November 8, 2020-January 2, 2021". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 29 (2): 426–430. doi:10.3201/eid2902.220959. ISSN 1080-6059. PMC 9881797. PMID 36639132.

- "Maintaining HIPAA Privacy with Contact Tracing". The HIPAA E-TOOL®. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- Volkin, Samuel (2020-05-26). "Digital contact tracing poses ethical challenges". The Hub. Retrieved 2022-11-14.

- Lucivero, Federica; Hallowell, Nina; Johnson, Stephanie; Prainsack, Barbara; Samuel, Gabrielle; Sharon, Tamar (2020). "COVID-19 and Contact Tracing Apps: Ethical Challenges for a Social Experiment on a Global Scale". Journal of Bioethical Inquiry. 17 (4): 835–839. doi:10.1007/s11673-020-10016-9. ISSN 1176-7529. PMC 7445718. PMID 32840842.

- "Ethical practice in isolation, quarantine & contact tracing". American Medical Association. 2020-04-28. Retrieved 2022-11-14.

Sources

- Robertson, LS. Roads to COVID-19 Containment and Spread. New York: Austin Macauley, 2023.