Conte (literature)

Conte (pronounced [kɔ̃t]) is a literary genre of tales, often short, characterized by fantasy or wit.[1] They were popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries until the genre became merged with the short story in the nineteenth century. Distinguishing contes from other literary genres is notoriously difficult due to the various meanings of the French term conte that span folktales, fairy tales, short stories, oral tales, and fables.

Definition

Conte comes from the French word conter, "to relate".[2] The French term conte encompasses a wide range of narrative forms that are not limited to written accounts. No clear English equivalent for conte exists in English as it includes folktales, fairy tales, short stories, oral tales,[3] and to lesser extent fables.[4] This makes conte notoriously difficult to define precisely.[5]

A conte is generally longer than a short story but shorter than a novel.[2] In this sense, contes can be called novellas.[6] Contes are contrasted with short stories not only in length but subject matter. Whereas short stories (nouvelles) are about recent ("novel") events, contes tend to be either fairy tales or philosophical stories.[7] Nouvelles, too, could be oral.[8] Contes are often adventure stories,[7] characterized by fantasy, wit, and satire. It may have moral or philosophical underpinnings, but is generally not interested in psychological depth or circumstantial detail. They may be profound, but not "weighty". These generic characteristics also contribute to their short length.[9] Contes can be either in prose or verse.[10]

History

Contes were popular in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The distinction between contes and short stories was largely obsolete by the nineteenth century when the genres became merged.[7] Reflective of this, the English term "short story" was coined in 1884 by Brander Matthews.[11]

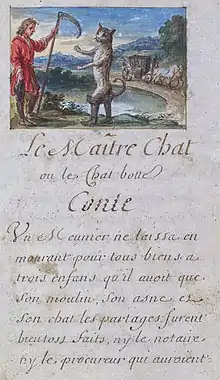

Famous examples of contes include Contes et nouvelles en vers by Jean de La Fontaine, Histoires ou contes du temps passé by Charles Perrault, and Contes cruels by Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam,[2] the last of which spawned a subgenre called conte cruel.[12]

Voltaire is said to have invented the genre of philosophical conte,[13] also practiced by Denis Diderot.[7] However, according to Edmund Gosse, "those brilliant stories" by Voltaire – Candide, Zadig, L'Ingénu, La Princesse de Babylone, and The White Bull – "are not, in the modern sense, contes at all. The longer of these are romans [novels], the shorter nouvelles, not one has the anecdotical unity required by a conte."[13] While it is possible that Voltaire drew inspiration to his contes from an oral source, namely his performances to Louise Bénédicte de Bourbon early in his career, he only published contes after his exile.[14]

Francophone contes also exist outside of France.[15] For instance, Lafcadio Hearn incorporated creole contes in his works.[16]

See also

- Anthology

- Conte cruel

- Drabble

- Flash fiction, also known as microfiction

- Irish short story

- Literary journal

- Minisaga

- Sketch story

- Tall tale

- Vignette

References

Citations

- Collins English Dictionary 2014.

- Encyclopedia Britannica 1999.

- Carruthers & McCusker 2010, p. 1.

- Howells 2011, p. 369.

- Farrant 2010, pp. 74–75.

- Grenier 2014, p. 87.

- Fallaize 2002, p. xii.

- Farrant 2010, p. 75n4.

- Mullan 2008, p. 151.

- Francis 2010, p. 19n1.

- Farrant 2010, p. 75n5.

- Stableford 2004, pp. 72–73.

- Gosse 1911, p. 24.

- Francis 2010, p. 19.

- Carruthers & McCusker 2010, p. 2.

- Gallagher 2010, p. 133.

Works cited

- Carruthers, Janice; McCusker, Maeve (2010). "Contextualising the Oral-written Dynamic in the French and Francophone conte". In Carruthers, Janice; McCusker, Maeve (eds.). The Conte: Oral and Written Dynamics. Oxford: Peter Lang. pp. 1–15. ISBN 978-3-03911-870-0.

- "conte". Collins English Dictionary: Complete and Unabridged (12th ed.). 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2020 – via TheFreeDictionary.com.

- "Conte". Encyclopedia Britannica. 1 September 1999. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- Fallaize, Elizabeth, ed. (2002). "Introduction". The Oxford Book of French Short Stories. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. xi–xxi. ISBN 978-0-19-288037-6.

- Farrant, Tim (2010). "Definition, repression, and the oral-literary interface in the French literary conte from the 'folie du conte' to the Second Empire". In Carruthers, Janice; McCusker, Maeve (eds.). The Conte: Oral and Written Dynamics. Oxford: Peter Lang. pp. 73–91. ISBN 978-3-03911-870-0.

- Francis, Richard (2010). "The Shadow of Orality in the Voltaire conte". In Carruthers, Janice; McCusker, Maeve (eds.). The Conte: Oral and Written Dynamics. Oxford: Peter Lang. pp. 19–33. ISBN 978-3-03911-870-0.

- Gallagher, Mary (2010). "The Creole Folktale in the Writing of Lafcadio Hearn: An Aesthetic of Mediation". In Carruthers, Janice; McCusker, Maeve (eds.). The Conte: Oral and Written Dynamics. Oxford: Peter Lang. pp. 133–151. ISBN 978-3-03911-870-0.

- Gosse, Edmund William (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 24.

- Grenier, Roger (2014). Palace of Books. Translated by Kaplan, Alice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-23259-1.

- Howells, Robin (2011). "The Eighteent-century conte". In Burgwinkle, William; Hammond, Nicholas; Wilson, Emma (eds.). The Cambridge History of French Literature. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 369–377. ISBN 978-1-316-17598-9.

- Mullan, John (2008). How Novels Work. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-162292-2.

- Stableford, Brian M. (2004). "Conte cruel". Historical Dictionary of Science Fiction Literature. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-0-8108-4938-9.