Counterpoint

In music, counterpoint is the relationship between two or more musical lines (or voices) which are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour.[1] It has been most commonly identified in the European classical tradition, strongly developing during the Renaissance and in much of the common practice period, especially in the Baroque period. The term originates from the Latin punctus contra punctum meaning "point against point", i.e. "note against note".

In Western pedagogy, counterpoint is taught through a system of species (see below).

There are several different forms of counterpoint, including imitative counterpoint and free counterpoint. Imitative counterpoint involves the repetition of a main melodic idea across different vocal parts, with or without variation. Compositions written in free counterpoint often incorporate non-traditional harmonies and chords, chromaticism and dissonance.

General principles

The term "counterpoint" has been used to designate a voice or even an entire composition.[2] Counterpoint focuses on melodic interaction—only secondarily on the harmonies produced by that interaction. In the words of John Rahn:

It is hard to write a beautiful song. It is harder to write several individually beautiful songs that, when sung simultaneously, sound as a more beautiful polyphonic whole. The internal structures that create each of the voices separately must contribute to the emergent structure of the polyphony, which in turn must reinforce and comment on the structures of the individual voices. The way that is accomplished in detail is ... 'counterpoint'.[3]

Work initiated by Guerino Mazzola (born 1947) has given counterpoint theory a mathematical foundation. In particular, Mazzola's model gives a structural (and not psychological) foundation of forbidden parallels of fifths and the dissonant fourth. Octavio Agustin has extended the model to microtonal contexts.[4][5]

In counterpoint, the functional independence of voices is the prime concern. The violation of this principle leads to special effects, which are avoided in counterpoint. In organ registers, certain interval combinations and chords are activated by a single key so that playing a melody results in parallel voice leading. These voices, losing independence, are fused into one and the parallel chords are perceived as single tones with a new timbre. This effect is also used in orchestral arrangements; for instance, in Ravel’s Bolero #5 the parallel parts of flutes, horn and celesta resemble the sound of an electric organ. In counterpoint, parallel voices are prohibited because they violate the homogeneity of musical texture when independent voices occasionally disappear turning into a new timbre quality and vice versa.[6][7]

Development

Some examples of related compositional techniques include: the round (familiar in folk traditions), the canon, and perhaps the most complex contrapuntal convention: the fugue. All of these are examples of imitative counterpoint.

Examples from the repertoire

There are many examples of song melodies that are harmonically interdependent yet independent in rhythm and melodic contour. For example, "Frère Jacques" and "Three Blind Mice" combine euphoniously when sung together. A number of popular songs that share the same chord progression can also be sung together as counterpoint. A well-known pair of examples is "My Way" combined with "Life on Mars".[8]

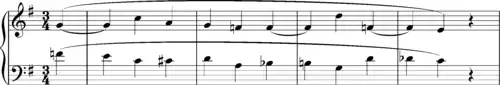

Bach's 3-part Invention in F minor combines three independent melodies:

According to pianist András Schiff, Bach's counterpoint influenced the composing of both Mozart and Beethoven. In the development section of the opening movement of Beethoven's Piano Sonata in E minor, Beethoven demonstrates this influence by adding "a wonderful counterpoint" to one of the main themes.[9]

A further example of fluid counterpoint in late Beethoven may be found in the first orchestral variation on the "Ode to Joy" theme in the last movement of Beethoven's Symphony No. 9, bars 116–123. The famous theme is heard on the violas and cellos, while "the basses add a bass-line whose sheer unpredictability gives the impression that it is being spontaneously improvised. Meantime a solo bassoon adds a counterpoint that has a similarly impromptu quality."[10]

In the Prelude to Richard Wagner's opera Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, three themes from the opera are combined simultaneously. According to Gordon Jacob, "This is universally and justly acclaimed as an extraordinary feat of virtuosity."[11] However, Donald Tovey points out that here "the combination of themes ... unlike classical counterpoint, really do not of themselves combine into complete or euphonious harmony."[12]

One spectacular example of 5-voice counterpoint can be found in the finale to Mozart's Symphony No 41 ("Jupiter" Symphony). Here five tunes combine simultaneously in "a rich tapestry of dialogue":[13]

See also Invertible counterpoint.

Species counterpoint

Species counterpoint was developed as a pedagogical tool in which students progress through several "species" of increasing complexity, with a very simple part that remains constant known as the cantus firmus (Latin for "fixed melody"). Species counterpoint generally offers less freedom to the composer than other types of counterpoint and therefore is called a "strict" counterpoint. The student gradually attains the ability to write free counterpoint (that is, less rigorously constrained counterpoint, usually without a cantus firmus) according to the given rules at the time.[14] The idea is at least as old as 1532, when Giovanni Maria Lanfranco described a similar concept in his Scintille di musica (Brescia, 1533). The 16th-century Venetian theorist Zarlino elaborated on the idea in his influential Le institutioni harmoniche, and it was first presented in a codified form in 1619 by Lodovico Zacconi in his Prattica di musica. Zacconi, unlike later theorists, included a few extra contrapuntal techniques, such as invertible counterpoint.

In 1725 Johann Joseph Fux published Gradus ad Parnassum (Steps to Parnassus), in which he described five species:

- Note against note;

- Two notes against one;

- Four notes against one;

- Notes offset against each other (as suspensions);

- All the first four species together, as "florid" counterpoint.

A succession of later theorists quite closely imitated Fux's seminal work, often with some small and idiosyncratic modifications in the rules. Many of Fux's rules concerning the purely linear construction of melodies have their origin in solfeggi. Concerning the common practice era, alterations to the melodic rules were introduced to enable the function of certain harmonic forms. The combination of these melodies produced the basic harmonic structure, the figured bass.

Considerations for all species

The following rules apply to melodic writing in each species, for each part:

- The final note must be approached by step. If the final is approached from below, then the leading tone must be raised in a minor key (Dorian, Hypodorian, Aeolian, Hypoaeolian), but not in Phrygian or Hypophrygian mode. Thus, in the Dorian mode on D, a C♯ is necessary at the cadence.[15]

- Permitted melodic intervals are the perfect unison, fourth, fifth, and octave, as well as the major and minor second, major and minor third, and ascending minor sixth. The ascending minor sixth must be immediately followed by motion downwards.

- If writing two skips in the same direction—something that must be only rarely done—the second must be smaller than the first, and the interval between the first and the third note may not be dissonant. The three notes should be from the same triad; if this is impossible, they should not outline more than one octave. In general, do not write more than two skips in the same direction.

- If writing a skip in one direction, it is best to proceed after the skip with step-wise motion in the other direction.

- The interval of a tritone in three notes should be avoided (for example, an ascending melodic motion F–A–B♮)[16] as is the interval of a seventh in three notes.

- There must be a climax or high point in the line countering the cantus firmus. This usually occurs somewhere in the middle of exercise and must occur on a strong beat.

- An outlining of a seventh is avoided within a single line moving in the same direction.

And, in all species, the following rules govern the combination of the parts:

- The counterpoint must begin and end on a perfect consonance.

- Contrary motion should dominate.

- Perfect consonances must be approached by oblique or contrary motion.

- Imperfect consonances may be approached by any type of motion.

- The interval of a tenth should not be exceeded between two adjacent parts unless by necessity.

- Build from the bass, upward.

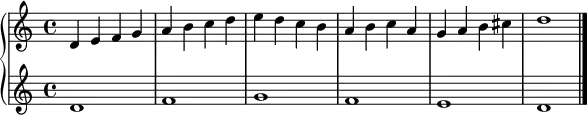

First species

In first species counterpoint, each note in every added part (parts being also referred to as lines or voices) sounds against one note in the cantus firmus. Notes in all parts are sounded simultaneously, and move against each other simultaneously. Since all notes in First species counterpoint are whole notes, rhythmic independence is not available.[17]

In the present context, a "step" is a melodic interval of a half or whole step. A "skip" is an interval of a third or fourth. (See Steps and skips.) An interval of a fifth or larger is referred to as a "leap".

A few further rules given by Fux, by study of the Palestrina style, and usually given in the works of later counterpoint pedagogues,[18] are as follows.

- Begin and end on either the unison, octave, or fifth, unless the added part is underneath, in which case begin and end only on unison or octave.

- Use no unisons except at the beginning or end.

- Avoid parallel fifths or octaves between any two parts; and avoid "hidden" parallel fifths or octaves: that is, movement by similar motion to a perfect fifth or octave, unless one part (sometimes restricted to the higher of the parts) moves by step.

- Avoid moving in parallel fourths. (In practice Palestrina and others frequently allowed themselves such progressions, especially if they do not involve the lowest of the parts.)

- Do not use an interval more than three times in a row.

- Attempt to use up to three parallel thirds or sixths in a row.

- Attempt to keep any two adjacent parts within a tenth of each other, unless an exceptionally pleasing line can be written by moving outside that range.

- Avoid having any two parts move in the same direction by skip.

- Attempt to have as much contrary motion as possible.

- Avoid dissonant intervals between any two parts: major or minor second, major or minor seventh, any augmented or diminished interval, and perfect fourth (in many contexts).

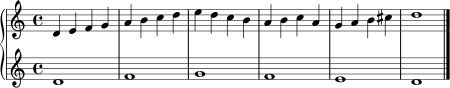

In the adjacent example in two parts, the cantus firmus is the lower part. (The same cantus firmus is used for later examples also. Each is in the Dorian mode.)

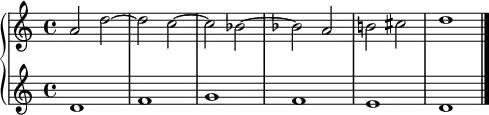

Second species

In second species counterpoint, two notes in each of the added parts work against each longer note in the given part.

Short example of "second species" counterpoint

Additional considerations in second species counterpoint are as follows, and are in addition to the considerations for first species:

- It is permissible to begin on an upbeat, leaving a half-rest in the added voice.

- The accented beat must have only consonance (perfect or imperfect). The unaccented beat may have dissonance, but only as a passing tone, i.e. it must be approached and left by step in the same direction.

- Avoid the interval of the unison except at the beginning or end of the example, except that it may occur on the unaccented portion of the bar.

- Use caution with successive accented perfect fifths or octaves. They must not be used as part of a sequential pattern. The example shown is weak due to similar motion in the second measure in both voices. A good rule to follow: if one voice skips or jumps try to use step-wise motion in the other voice or at the very least contrary motion.

Third species

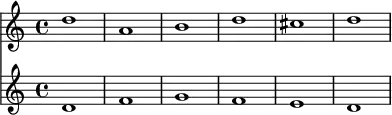

Short example of "third species" counterpoint

In third species counterpoint, four (or three, etc.) notes move against each longer note in the given part.

Three special figures are introduced into third species and later added to fifth species, and ultimately outside the restrictions of species writing. There are three figures to consider: The nota cambiata, double neighbor tones, and double passing tones.

Double neighbor tones: the figure is prolonged over four beats and allows special dissonances. The upper and lower tones are prepared on beat 1 and resolved on beat 4. The fifth note or downbeat of the next measure should move by step in the same direction as the last two notes of the double neighbor figure. Lastly a double passing tone allows two dissonant passing tones in a row. The figure would consist of 4 notes moving in the same direction by step. The two notes that allow dissonance would be beat 2 and 3 or 3 and 4. The dissonant interval of a fourth would proceed into a diminished fifth and the next note would resolve at the interval of a sixth.[15]

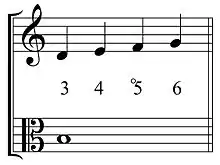

Fourth species

In fourth species counterpoint, some notes are sustained or suspended in an added part while notes move against them in the given part, often creating a dissonance on the beat, followed by the suspended note then changing (and "catching up") to create a subsequent consonance with the note in the given part as it continues to sound. As before, fourth species counterpoint is called expanded when the added-part notes vary in length among themselves. The technique requires chains of notes sustained across the boundaries determined by beat, and so creates syncopation. Also, it is important to note that a dissonant interval is allowed on beat 1 because of the syncopation created by the suspension. While it is not incorrect to start with a half note, it is also common to start 4th species with a half rest.

Short example of "fourth species" counterpoint

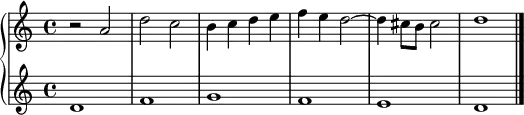

Fifth species (florid counterpoint)

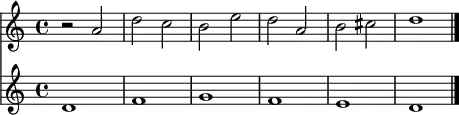

In fifth species counterpoint, sometimes called florid counterpoint, the other four species of counterpoint are combined within the added parts. In the example, the first and second bars are second species, the third bar is third species, the fourth and fifth bars are third and embellished fourth species, and the final bar is first species. In florid counterpoint it is important that no one species dominates the composition.

Short example of "Florid" counterpoint

Contrapuntal derivations

Since the Renaissance period in European music, much contrapuntal music has been written in imitative counterpoint. In imitative counterpoint, two or more voices enter at different times, and (especially when entering) each voice repeats some version of the same melodic element. The fantasia, the ricercar, and later, the canon and fugue (the contrapuntal form par excellence) all feature imitative counterpoint, which also frequently appears in choral works such as motets and madrigals. Imitative counterpoint spawned a number of devices, including:

- Melodic inversion

- The inverse of a given fragment of melody is the fragment turned upside down—so if the original fragment has a rising major third (see interval), the inverted fragment has a falling major (or perhaps minor) third, etc. (Compare, in twelve-tone technique, the inversion of the tone row, which is the so-called prime series turned upside down.) (Note: in invertible counterpoint, including double and triple counterpoint, the term inversion is used in a different sense altogether. At least one pair of parts is switched, so that the one that was higher becomes lower. See Inversion in counterpoint; it is not a kind of imitation, but a rearrangement of the parts.)

- Retrograde

- Whereby an imitative voice sounds the melody backwards in relation to the leading voice.

- Retrograde inversion

- Where the imitative voice sounds the melody backwards and upside-down at once.

- Augmentation

- When in one of the parts in imitative counterpoint the note values are extended in duration compared to the rate at which they were sounded when introduced.

- Diminution

- When in one of the parts in imitative counterpoint the note values are reduced in duration compared to the rate at which they were sounded when introduced.

Free counterpoint

Broadly speaking, due to the development of harmony, from the Baroque period on, most contrapuntal compositions were written in the style of free counterpoint. This means that the general focus of the composer had shifted away from how the intervals of added melodies related to a cantus firmus, and more toward how they related to each other.[19]

Nonetheless, according to Kent Kennan: "....actual teaching in that fashion (free counterpoint) did not become widespread until the late nineteenth century."[20] Young composers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, such as Mozart, Beethoven, and Schumann, were still educated in the style of "strict" counterpoint, but in practice, they would look for ways to expand on the traditional concepts of the subject.

Main features of free counterpoint:

- All forbidden chords, such as second-inversion, seventh, ninth etc., can be used freely as long as they resolve to a consonant triad

- Chromaticism is allowed

- The restrictions about rhythmic-placement of dissonance are removed. It is possible to use passing tones on the accented beat

- Appoggiatura is available: dissonance tones can be approached by leaps.

Linear counterpoint

Linear counterpoint is "a purely horizontal technique in which the integrity of the individual melodic lines is not sacrificed to harmonic considerations. "Its distinctive feature is rather the concept of melody, which served as the starting-point for the adherents of the 'new objectivity' when they set up linear counterpoint as an anti-type to the Romantic harmony."[2] The voice parts move freely, irrespective of the effects their combined motions may create."[21] In other words, either "the domination of the horizontal (linear) aspects over the vertical"[22] is featured or the "harmonic control of lines is rejected."[23]

Associated with neoclassicism,[22] the technique was first used in Igor Stravinsky's Octet (1923),[21] inspired by J. S. Bach and Giovanni Palestrina. However, according to Knud Jeppesen: "Bach's and Palestrina's points of departure are antipodal. Palestrina starts out from lines and arrives at chords; Bach's music grows out of an ideally harmonic background, against which the voices develop with a bold independence that is often breath-taking."[21]

According to Cunningham, linear harmony is "a frequent approach in the 20th century...[in which lines] are combined with almost careless abandon in the hopes that new 'chords' and 'progressions'...will result." It is possible with "any kind of line, diatonic or duodecuple".[23]

Dissonant counterpoint

Dissonant counterpoint was originally theorized by Charles Seeger as "at first purely a school-room discipline," consisting of species counterpoint but with all the traditional rules reversed. First species counterpoint must be all dissonances, establishing "dissonance, rather than consonance, as the rule," and consonances are "resolved" through a skip, not step. He wrote that "the effect of this discipline" was "one of purification". Other aspects of composition, such as rhythm, could be "dissonated" by applying the same principle.[24]

Seeger was not the first to employ dissonant counterpoint, but was the first to theorize and promote it. Other composers who have used dissonant counterpoint, if not in the exact manner prescribed by Charles Seeger, include Johanna Beyer, John Cage, Ruth Crawford-Seeger, Vivian Fine, Carl Ruggles, Henry Cowell, Carlos Chávez, John J. Becker, Henry Brant, Lou Harrison, Wallingford Riegger, and Frank Wigglesworth.[25]

References

- Laitz, Steven G. (2008). The Complete Musician (2 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-530108-3.

- Sachs & Dahlhaus 2001.

- Rahn, John (2000). Music Inside Out: Going Too Far in Musical Essays. intro. and comment. by Benjamin Boretz. Amsterdam: G+B Arts International. p. 177. ISBN 90-5701-332-0. OCLC 154331400.

- Mazzola, Guerino (2017). "The Topos of Music I: Theory". Computational Music Science. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-64364-9. ISBN 978-3-319-64363-2. ISSN 1868-0305. S2CID 4399053.

- Mozzalo, Guerino (2017). The Topos of Music I: Theory : Geometric Logic, Classification, Harmony, Counterpoint, Motives, Rhythm. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Tangian, Andranick (1993). Artificial Perception and Music Recognition. Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence. Vol. 746. Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-57394-4.

- Tangian, Andranick (1994). "A principle of correlativity of perception and its application to music recognition". Music Perception. 11 (4): 465–502. doi:10.2307/40285634. JSTOR 40285634.

- "Life on Mars" and "My Way" on YouTube, Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain

- Schiff, A. (2006) "Guardian Lecture on Beethoven Piano Sonata in E minor, Op. 90, accessed 8 August 2019

- Hopkins, Antony (1981, p. 275) The Nine Symphonies of Beethoven. London, Heinemann.

- Jacob, Gordon (1953, p. 14) Wagner Overture Die Meistersinger. Harmondsworth, Penguin

- Tovey, Donald Francis (1936, p. 127) Essays in Musical Analysis, Volume IV. Oxford University Press.

- Keefe, Simon P. (2003, p. 104) The Cambridge Companion to Mozart. Cambridge University Press.

- Jeppesen, Knud (1992) [1939]. Counterpoint: the polyphonic vocal style of the sixteenth century. trans. by Glen Haydon, with a new foreword by Alfred Mann. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-27036-X.

- Salzer & Schachter1989, p. .

- Arnold, Denis.; Scholes, Percy A. (1983). The New Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1877–1958. ISBN 0193113163. OCLC 10096883.

- Anon. "Species Counterpoint" (PDF). Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Victoria, Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2020. (archive from 23 October 2018)

- Fux, Johann Joseph 1660-1741 (1965). The study of counterpoint from Johann Joseph Fux's Gradus ad parnassum. The Norton library, N277 (Rev. ed.). New York: W. W. Norton.

- Kornfeld, Jono. "Free Counterpoint, Two Parts" (PDF). Retrieved 6 February 2023.

- Kennan, Kent (1999). Counterpoint (fourth ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. p. 4. ISBN 0-13-080746-X.

- Katz, Adele (1946). Challenge to Musical Tradition: A New Concept of Tonality (New York: A. A. Knopf), p. 340. Reprinted New York: Da Capo Press, 1972; reprinted n.p.: Katz Press, 2007, ISBN 1-4067-5761-6.

- Ulrich, Homer (1962). Music: a Design for Listening, second edition (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World), p. 438.

- Cunningham, Michael (2007). Technique for Composers, p. 144. ISBN 1-4259-9618-3.

- Charles Seeger, "On Dissonant Counterpoint," Modern Music 7, no. 4 (June–July 1930): 25–26.

- Spilker, John D., "Substituting a New Order": Dissonant Counterpoint, Henry Cowell, and the network of ultra-modern composers Archived 2011-08-15 at the Wayback Machine, Ph.D. dissertation, Florida State University College of Music, 2010.

Sources

- Sachs, Klaus-Jürgen; Dahlhaus, Carl (2001). "Counterpoint". In Stanley Sadie; John Tyrrell (eds.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (second ed.). London: Macmillan Publishers.

- Salzer, Felix; Schachter, Carl (1989). Counterpoint in Composition: The Study of Voice Leading. New York: Stanley Persky, City University of New York. ISBN 023107039X.

Further reading

- Kurth, Ernst (1991). "Foundations of Linear Counterpoint". In Ernst Kurth: Selected Writings, selected and translated by Lee Allen Rothfarb, foreword by Ian Bent, p. 37–95. Cambridge Studies in Music Theory and Analysis 2. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. Paperback reprint 2006. ISBN 0-521-35522-2 (cloth); ISBN 0-521-02824-8 (pbk)

- Agustín-Aquino, Octavio Alberto; Junod, Julien; Mazzola, Guerino (2015). Computational Counterpoint Worlds: Mathematical Theory, Software, and Experiments. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-11236-7. ISBN 978-3-319-11235-0. S2CID 7203604.

- Prout, Ebenezer (1890). Counterpoint: Strict and Free. London: Augener & Co.

- Spalding, Walter Raymond (1904). Tonal Counterpoint: Studies in Part-writing. Boston, New York: A. P. Schmidt.

External links

- An explanation and teach yourself method for Species Counterpoint

- ntoll.org: Species Counterpoint by Nicholas H. Tollervey

- Orima: The History of Experimental Music in Northern California: On Dissonant Counterpoint by David Nicholls from his American Experimental Music: 1890–1940

- Virginia Tech Multimedia Music Dictionary: Dissonant counterpoint examples and definition

- Counterpointer:Software tutorial for the study of counterpoint by Jeffrey Evans

- "Bach as Contrapuntist" by Dan Brown, music critic from Cornell University, from his web book Why Bach?

- "contrapuntal—a collaborative arts project by Benjamin Skepper"

- Principles of Counterpoint, by Alan Belkin