Head house

A head house or headhouse may be an enclosed building attached to an open-sided shed, or the aboveground part of a subway station.

Markets

In the 18th and early 19th centuries, head houses were often civic buildings such as town halls or courthouses located at the end of an open market shed; one example is the former market and firehouse from which Philadelphia's Head House Square takes its name.

Mines

In mining, a headhouse is the housing of the headworks of various types of machinery used for moving coal to the surface, or men to or from it.

Transportation

Railroads

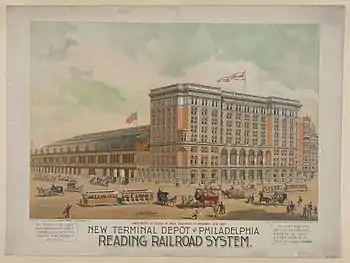

Since the mid-19th century, in the United States, a head house has often been the part of a passenger train station that does not house the tracks and platforms. Elsewhere, the same part of a station is known as the station building.

In particular, it often contains the ticket counters, waiting rooms, toilets and baggage facilities. It might also include the passenger concourses and walkways between the platforms and other facilities. The head house at Philadelphia's Reading Terminal, which fronts a two level shed with tracks and platforms placed above a covered market, combined both the older and newer meanings of the word.

Larger terminals had amenities that were contained within their own distinct building, which was separate from the railroad. For instance, when Cincinnati Union Terminal opened in 1933, the head house held a restaurant, lunch room, ice cream shop, news agent, drug store, small movie theater, men's and women's lounges, and restrooms that included changing rooms and showers.[1]

Subways

In subway systems, a head house is the part of a subway station that is above ground, which contain escalators, elevators and ticket agents.

On the New York City Subway, a head house is called a "Control House". They were built, and are still used in certain locations (such as at Broadway and West 72nd Street), where a simple staircase or kiosk was not desirable. During the design and construction of the city's original subway line opened by the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) in 1904, control houses were treated as integral architectural features of the system. In 1901, William Barclay Parsons, chief engineer for the Board of Rapid Transit Railroad Commissioners, had traveled to Boston with architect Christopher LaFarge, where he was apparently inspired by the ornamental houses he saw used as entrances to the Tremont Street subway.[2] In response, architects Heins & LaFarge designed each IRT control house to be an attractive exterior feature of the transit network system that was in keeping with its location. The buildings, which are examples of the Beaux-Arts style, are similar to other ground-level structures on the IRT, such as the powerhouses and sub-stations.

See also

- Baltimore's former President Street Station, now the Baltimore Civil War Museum

- former Chicago and North Western Terminal

- former Grand Central Depot in New York City

- Howrah Junction railway station in India

- Reading Terminal in Philadelphia

- St. Louis Union Station

- Washington Union Station

References

- "Cincinnati's New Union Terminal", Railway Age, Vol. 94, No. 16, April 22, 1938 (available as a reprint—The Cincinnati Union Terminal—from the Cincinnati Railroad Club)

- Framberger, David J. "Architectural Designs For New York's First Subway". Survey Number HAER NY-122, pp. 365-412. National Park Service Department of the Interior Washington, DC. 20240. Retrieved 26 December 2010.