Controversia

A controversia is an exercise in rhetoric; a form of declamation in which the student speaks for one side in a notional legal case such as treason or poisoning. The facts of the matter and relevant law are presented in a persuasive manner, in the style of a legal counsel.[1]

History

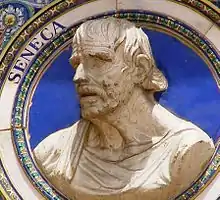

Like thesis and suasoria, controversia originated in ancient Greece.[2] It was a rhetorical exercise and is associated with the history of Greek education.[2] An early form of the Roman controversia was described by Seneca as a combination of thesis (propositio) and hypothesis (causa).[3] The former pertained to the general topic being proposed for discussion from one or more points of view without delimitation of particular persons or circumstances. On the other hand, hypothesis referred to the particular controversy given by circumstances to a deliberating body for adjudication.[3] Based on an example of the exercise cited in Cicero's De oratore, it is cited that controversia emerged at least during 55 BCE, the date of De oratore's composition.[4]

The exercise was used in ancient Rome, where it was, with the suasoria, the final stage of a course in rhetoric at an academy.[5] Controversia and suasoria provided students the best window into the play-speech of schooling and declamatory performance that formed the bases of ancient rhetorical mentality.[6] As a form of disputation, it consists of a statement of one or more laws, which was followed by the circumstances of a fictitious case in which the speaker argued one side or the other.[4]

While suasoria required students to persuade a person (e.g., judge) or a group (e.g., jury) to act a certain way, controversia required a student to either prosecute or defend a person in a given legal case.[7] The controversia is also distinguished from suasoria because of the complexity of its structural system of argument and the greater range of situations and characters employed.[6] The distinction can also be explained in the way students who focused on this exercise end up as forensic orators while those who trained in suasoria followed a career in deliberative rhetoric.[8] The process put students in the position of one offering reasoned advice and, as a result, earn experience in the application of the procedure of deliberative theory.[9]

Seneca the Elder was an expert rhetorician and, from memory, compiled a set of classical themes for this exercise: the Controversiæ.[10] Controversia is demonstrated in the case of Quintillian's Declamationes Minores where suasoria was turned into this exercise by using a courtroom as a setting.[11] The plot addressed the issue of a son who married the daughter of his father's enemy so he could use the dowry to ransom his who was captured by pirates.[11] Quintillian used controversia as an analytical method, which involved a survey of diversity of opinions on a specific topic to identify positions as well as the pros and cons of each side.[12] He also introduced the term controversia figurata (figured speech) to explain an excitement of suspicion for the purpose indicating that what is meant is other than the words would seem to imply and such “meaning is not in this case contrary to that which we express, as in the case of irony, but rather a hidden meaning which is left to the hearer to discover.”[13]

References

- Heinrich Lausberg, translated by David E. Orton (1998), Handbook of Literary Rhetoric, BRILL, pp. 500–501, ISBN 9789004107052

- Fairweather, Janet (2007-11-29). Seneca the Elder. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 104. ISBN 9780521231015.

- Trimpi, Wesley (2009). Muses of One Mind: The Literary Analysis of Experience and Its Continuity. Eugene, Oregon: Wipf and Stock Publishers. p. 307. ISBN 9781608991556.

- MacDonald, Michael J. (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Rhetorical Studies. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780190681845.

- Susanna Morton Braund (1997). "Declamation and contestation in satire". Roman Eloquence: Rhetoric in Society and Literature. Routledge. p. 148. ISBN 9780415125444.

- Sloane, Thomas (2001). Encyclopedia of Rhetoric, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 168–169. ISBN 9780195125955.

- Zerbe, Michael (2007). Composition and the Rhetoric of Science: Engaging the Dominant Discourse. Southern Illinois University Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780809327409.

- Winter, Bruce (1997). Philo and Paul Among the Sophists. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 31. ISBN 0521591082.

- Bonner, Stanley F. (1977). Education in Ancient Rome: From the Elder Cato to the Younger Pliny. Los Angeles, CA: Univ of California Press. p. 272. ISBN 0-520-03439-2.

- The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome, vol. 1, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 276, ISBN 9780195170726

- Dominik, William; Hall, Jon (2010). A Companion to Roman Rhetoric. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & sons. p. 302. ISBN 9781405120913.

- Mendelson, Michael (2002). Many Sides: A Protagorean Approach to the Theory, Practice and Pedagogy of Argument. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 184. ISBN 1402004028.

- Vegge, Ivar (2008). 2 Corinthians, a Letter about Reconciliation: A Psychagogical, Epistolographical, and Rhetorical Analysis. Tubingen, Germany: Mohr Siebeck. pp. 128–129. ISBN 978-3-16-149302-7.