Contubernium

Contubernium was a quasi-marital relationship in ancient Rome between two slaves or between a slave (servus) and a free citizen.[2][3] A slave involved in such a relationship was called contubernalis,[4] the basic and general meaning of which was "companion"; the word seems sometimes to have been used as an enduring term of endearment even after a formerly enslaved couple achieved a legal status that allowed them to marry formally.[5] Contubernium was intended to be a lasting, ideally permanent union based on marital affection (affectio maritalis),[6] though the slave's owner retained the power to dissolve the union.[7]

Between two slaves

Roman law regarded the slave as property; slaves lacked legal personhood and therefore could not enter into contracts on their own behalf, including legally sanctioned forms of marriage (matrimonium). Some slaves, however, were permitted or encouraged to form family units—permanent heterosexual unions within which "natural children" (liberi naturales or vernae) might be reared.[8] In inscriptions, most contubernales whose status can be identified are slaves, though liberti and libertae (freedpersons) are also frequent. [9]

On a country estate (villa), a male slave who had proven his reliability might allowed the privilege of contubernium with a fellow female slave (conserva).[10] The agricultural writer Columella says that it is particularly desirable for the vilicus (farm manager or overseer, who was often but not always a slave or former slave) to have this kind of relationship.[11] Vernae, slaves who had been born and reared within the household of their enslaved mother, were more likely to be allowed to cohabit as a couple and to rear their own children.[12] Any children born from these unions would increase the master's wealth.[13]

Contubernium might be allowed between two slaves who belonged to two different owners.[14]

Between a free woman and a male slave

If a male slave entered into contubernium with a free woman, according to the ius gentium (customary international law) the children were born free.

While contubernium between slaves owned by two different masters might be permitted, it was contestable between a free woman and another citizen's male slave.[15] The Senatus consultum Claudianum established that if after three warnings from the slave's owner the free woman did not cease her sexual relationship with their slave, she would become a slave to the same owner.[16][17] The purpose of this law was not to regulate the free woman's morality but to protect private property and maximize the male slave's productivity.[18]

According to a sample of 260 recorded contubernia, excluding quasi-marriage between slaves, relationships in which the woman was the free citizen and the man was the slave are prevalent.[19] As Susan Treggiari, author of the study, observed:[14]

For a free woman of a certain class (e.g. the daughter of an imperial freedman) to marry an upwardly-mobile slave civil servant was to her advantage. A woman slave had no status connected with her job which would attract a free husband. (Women in the familia Caesaris usually married fellow slaves.) Secondly, there was a grave disadvantage of a slave wife. If a slave man "married" a free woman, the children were born free iure gentium (with exceptions introduced by the Senatus consultum Claudianum and sometimes applied). But a slave woman with a free husband (with a few exceptions) bore slave children.

Between a free man and a female slave

If the male participant in the relationship was free but the woman was a slave, their children would be born slaves. The slave-owner therefore could free the slave, and if he was a man of the upper classes, he might make her his concubina (see concubinatus). If he was of lower status, he could free her and enter into a legal marriage. In either case, the union would not be contubernium.[21]

A man of senatorial rank could not legally marry a freedwoman (liberta).[22] After the death of his wife, Vespasian maintained a relationship with Caenis, the freedwoman and former secretary of Antonia Minor, even when he became emperor, at which time she would have been about 58 years old. Their relationship began when she was about 20. In his Life of Vespasian, Suetonius calls their union a contubernium but also refers to Caenis as a concubina in a position that was all but a legal wife, until her death in AD 74.[23]

See also

Notes

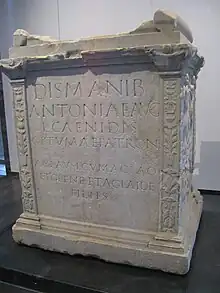

- AE 1947, 77 = SEG 21, 1058

- Oxford Classical Dictionary 1949.

- Stocquart 1907, p. 305.

- Treggiari 1981, p. 43: "In literature, contubernalis is vox propria for a slave ‘wife’ or ‘husband’ in Columella and Petronius; this is also the usual sense in the jurists and the commonest sense in the inscriptions. But contubernium is also a quasi-marital relationship involving one slave partner rather than two. The Elder Seneca has this sense, as do the jurists."

- Beryl Rawson, "Roman Concubinage and Other De Facto Marriages," Transactions of the American Philological Association 104 (1974), pp. 279, 293–294.

- Susan Treggiari, "Concubinae," Papers of the British School at Rome 49 (1981), p. 59.

- Karen K. Hersch, The Roman Wedding: Ritual and Meaning in Antiquity (Cambridge University Press, 2010), p. 28.

- Adolf Berger, entry on contubernium, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (American Philological Society, 1953, 1991), p. 564.

- Rawson, "Roman Concubinage," p. 294.

- William V. Harris, "Towards a Study of the Roman Slave Trade," Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome 36 (1980), p. 120.

- Harris, "Towards a Study of the Slave Trade," p. 120, citing Columella 1.8.4.

- John Madden "Slavery in the Roman Empire: Numbers and Origins," Classics Ireland 3 (1996), p. 115, citing Columella 1.8.19 and Varro, De re rustica 1.17.5, 7 and 2.126.

- Eva Cantarella, Bisexuality in the Ancient World (Yale University Press, 1992), p. 103.

- Treggiari 1981, p. 54.

- Cantarella 1992, p. 103.

- A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities 1875.

- Harper 2010.

- Cantarella 2015.

- Treggiari 1981, p. 45.

- [[Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum}CIL]] 6.12037

- Treggiari 1981, p. 53:

- Rawson, "Roman Concubinage," p. 282.

- Rawson, "Roman Concubinage," citing Suetonius, Vespasian 3 (paene iustae uxoris loco).

Bibliography

- Finley, M. I.; Keith, Emile (1949). "Contubernium". Oxford Classical Dictionary. OUP. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.1803. S2CID 165984407. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- Stocquart, Emile (March 1907). Sherman, Charles Phineas (ed.). Translated by Bierkan, Andrew T. "Marriage in Roman law". Yale Law Journal. 16 (5): 303–327. doi:10.2307/785389. JSTOR 785389. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

- Treggiari, Susan (1981). "Contubernales". Phoenix. CAC. 35 (1): 42–69. doi:10.2307/1087137. JSTOR 1087137.

- Grubbs, Judith Evans (2002). Women and the Law in the Roman Empire: A Sourcebook on Marriage, Divorce and Widowhood. Routledge Sourcebooks for the Ancient World. Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781134743926.

- Cantarella, Eva (2015). Istituzioni di diritto romano [Institutions of Roman law] (in Italian). Mondadori. ISBN 978-8800746083.

- Rawson, Beryl (1974). "Roman Concubinage and Other De Facto Marriages". Transactions of the American Philological Association. JHUP. 104: 279–305. doi:10.2307/2936094. JSTOR 2936094.

- Finley, M. I. (1875). "Senatusconsultum Claudianum". A Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities. London: John Murray. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139794602. ISBN 9781139794602. Retrieved 2020-09-18.

- Harper, Kyle (December 2010). "The SC Claudianum in the codex Theodosianus: Social history and legal texts". The Classical Quarterly. CUP. 60 (2): 610–638. doi:10.1017/S0009838810000108. S2CID 162980885.

- Cantarella, Eva (1992). Bisexuality in the Ancient World. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04844-5.

- McGinn, Thomas A.J. (1998). Prostitution, Sexuality and the Law in Ancient Rome. Oxford University Press.

- Hubbard, Thomas K. (2003). Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents. University of California Press.