Wine glass

A wine glass is a type of glass that is used to drink and taste wine. Most wine glasses are stemware (goblets), i.e., they are composed of three parts: the bowl, stem, and foot.

Shapes

The effect of glass shape on the taste of wine has not been demonstrated decisively by any scientific study and remains a matter of debate. One study[1] suggests that the shape of the glass is important, as it concentrates the flavour and aroma (or bouquet) to emphasize the varietal's characteristic. One common belief is that the shape of the glass directs the wine itself into the best area of the mouth for the varietal[2] despite flavour being perceived by olfaction in the upper nasal cavity, not the mouth. The importance of wine glass shape could also be based on false ideas about the arrangement of different taste buds on the tongue, such as the discredited tongue map.

Most wine glasses are stemware, that is they are goblets composed of three parts: the bowl, stem, and foot. In some designs, the opening of the glass is narrower than the widest part of the bowl to concentrate the aroma.[3] Others are more open, like inverted cones. In addition, "stemless" wine glasses (tumblers) are available in a variety of sizes and shapes.[4] The latter are typically used more casually than their traditional counterparts.

Some common types of wine glasses are described below.

Red wine glasses

Glasses for red wine are characterized by their rounder, wider bowl, which increases the rate of oxidation. As oxygen from the air chemically interacts with the wine, flavor and aroma are believed to be subtly altered. This process of oxidation is generally considered more compatible with red wines, whose complex flavours are said to be smoothed out after being exposed to air. Red wine glasses can have particular styles of their own, such as

- Bordeaux glass: tall with a broad bowl, and is designed for full bodied red wines like Cabernet Sauvignon and Syrah as it directs wine to the back of the mouth.

- Burgundy glass: broader than the Bordeaux glass, it has a bigger bowl to accumulate aromas of more delicate red wines such as Pinot noir. This style of glass directs wine to the tip of the tongue.[5]

White wine glasses

White wine glasses vary enormously in size and shape, from the delicately tapered Champagne flute, to the wide and shallow glasses used to drink Chardonnay. Different shaped glasses are used to accentuate the unique characteristics of different styles of wine. Wide-mouthed glasses function similarly to red wine glasses discussed above, promoting rapid oxidation which alters the flavor of the wine. White wines which are best served slightly oxidized are generally full-flavored wines, such as oaked chardonnay. For lighter, fresher styles of white wine, oxidation is less desirable as it is seen to mask the delicate nuances of the wine. To preserve a crisp, clean flavored wine, many white wine glasses will have a smaller mouth, which reduces surface area and in turn, the rate of oxidization. In the case of sparkling wine, such as Champagne or Asti, an even smaller mouth is used to keep the wine sparkling longer in the glass.

Champagne flutes

Champagne flutes are characterised by a long stem with a tall, narrow bowl on top. The shape is designed to keep sparkling wine desirable during its consumption. Just as with wine glasses, the flute is designed to be held by the stem to help prevent the heat from the hand from warming the liquid inside. The bowl itself is designed in a manner to help retain the signature carbonation in the beverage. This is achieved by reducing the surface area at the opening of the bowl. Additionally, the flute design adds to the aesthetic appeal of champagne, allowing the bubbles to travel further due to the narrow design, giving a more pleasant visual appeal.

Use

Some authors recommend one holds the glass by the stem, to avoid warming the wine and smudging the bowl.[3]

Materials

High quality wine glasses once were made of lead glass, which has a higher index of refraction and is heavier than ordinary glass, but health concerns regarding the ingestion of lead resulted in their being replaced by lead-free glass.[6] Wine glasses, with the exception of the hock glass, are generally not coloured or frosted as doing so would diminish appreciation of the wine's colour.[3] There used to be an ISO standard (ISO/PAS IWA 8:2009) for glass clarity and freedom from lead and other heavy metals, but it was withdrawn.[7]

Some producers of high-end wine glasses such as Schott Zwiesel have pioneered methods of infusing titanium into the glass to increase its durability and reduce the likelihood of the glass breaking.[8]

Decoration

In the 18th century, glass makers would draw spiral patterns in the stem as they made the glass. If they used air bubbles it was called an airtwist; if they used threads, either white or coloured, it would be called opaque twist.[9]

ISO wine tasting glass

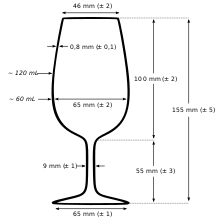

The International Organization for Standardization has a specification (ISO 3591:1977) for a wine-tasting glass. It consists of a cup (an "elongated egg") supported on a stem resting on a base.

The glass of reference is the INAO wine glass, a tool defined by specifications of the French Association for Standardization (AFNOR), which was adopted by INAO as the official glass in 1970, received its standard AFNOR in June 1971 and its ISO 3591 standard in 1972.[10] The INAO has not submitted a file at the National Institute of Industrial Property, it is therefore copied en masse and has gradually replaced other tasting glasses in the world.[11]

The glass must be lead crystal (9% lead). Its dimensions give it a total volume between 210 mL and 225 mL, they are defined as follows:

- Diameter of the rim: 46 mm

- Calyx height: 100 mm

- Height of the foot: 55 mm

- Shoulder diameter: 65 mm

- Foot diameter: 9 mm

- Diameter of the base: 65 mm

The opening is narrower than the convex part so as to concentrate the bouquet. The capacity is approximately 215 ml, but it is intended to take a 50 ml pour.[12] Some glasses of a similar shape, but with different capacities, may be loosely referred to as ISO glasses, but they form no part of the ISO specification.

Measures in licensed premises

In the UK there has been a steady trend away from serving wine in the standard size of 125 ml, towards the larger size of 250 ml, even though, since 1 October 2010, alcohol retailers have been obliged by law to offer customers the choice of a smaller measure. A code of practice, introduced in April 2010 as an extension to the Licensing Act 2003, contains five mandatory conditions for the sale of alcohol, including an obligation for the licensee to make the customer aware that small measures are available.[13]

In the United States, most laws governing alcohol exist at the state level. Federal law does not provide any guidance on a standard pour size, but 150 millilitres (5 US fl oz) is seen as typical for restaurants (one fifth of a standard 750 ml wine bottle), and with pour sizes for tastings typically being half as large.[14]

Capacity measure

As a supplemental unit of apothecary measure, the wineglass (also known as wineglassful, pl. wineglassesful, or cyathus vinarius in pharmaceutical Latin) was defined as 1⁄8 of a pint, (2 fluid ounces by US measure, or 21⁄2 fluid ounces by imperial measure).[15][16] An older version (before c. 1800) was 11⁄2 fluid ounces.[17] These units bear little relation to the capacity of most contemporary wineglasses, or to the ancient Roman cyathus.

See also

References

- "Wine Snobs Are Right: Glass Shape Does Affect Flavor". Scientific American. 14 April 2015. Archived from the original on 4 October 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2019.

- Zwerdling, Daniel (August 2004). "Shattered Myths". Gourmet Magazine. Archived from the original on 24 March 2008.

- Cech, Mary; Schacht, Jennie (29 September 2005). The Wine Lover's Dessert Cookbook: Recipes and Pairings for the Perfect Glass of Wine. Chronicle Books. pp. 32–. ISBN 978-0-8118-4237-2.

- Asimov, Eric (16 March 2017). "One Wine Glass to Rule Them All". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- "Types of Wine Glasses". webstaurantstore.com. WebstaurantStore. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- Questions and Answers About Lead in Tableware Archived 2017-09-06 at the Wayback Machine. California Department of Public Health

- "IWA 8:2009 - Tableware, giftware, jewellery, luminaries -- Glass clarity -- Classification and test method". ISO. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- Fish, Tim. "It's Just a Wineglass". Wine Spectator. Retrieved 24 August 2018.

- Clarke, Michael. (2001). The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art Terms. Oxford University Press.

- "Le verre ISO ou verre INAO". verres-a-vin.fr. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- Le verre et le vin de la cave à la table du |XVII à nos jours (Glass and Wine from the Cellar to the Table from the 17th century to the Present) Christophe Bouneau, Michel Figeac, 2007. Centre d'études des mondes moderne et contemporain. In French

- "ISO 3591:1977". ISO.org. Retrieved 9 February 2012. (payment required)

- Victoria Moore (4 January 2014). "Fight for your right to a smaller glass of wine". The Daily Telegraph. Wine. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Bell, Emily (28 February 2016). "What is a Standard Pour and Why Should I Care?". Vinepair. Retrieved 16 June 2023.

- Edward Quin Thornton (1901). Dose-book and Manual of Prescription-writing. W.B. Saunders. p. 20. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- Weeks-Shaw, Clara S. (1808). A text-book of nursing: for the use of training schools, families, and private students. D. Appleton. p. 108. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- James, Robert (1747). Pharmacopoeia universalis: or, A new universal English dispensatory. Containing. An account of all the natural and artificial implements and instruments of pharmacy, together with the processes and operations, whereby changes are induced in natural bodies for medicinal purposes .. With a copious index to the whole. Printed for J. Hodges and J. Wood. p. 623. Retrieved 21 December 2011.